From Socialist Review, 1980 : 8, 18 September–16 October 1980, pp.–18–21.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

You still meet people who insist that the ‘planned’ economies of Eastern Europe cannot, by definition, run into the same crises as afflict the ‘private’ (more accurately, state monopoly) capitalisms of the West.

It is a contention that should have little credibility after the events that have been shaking Poland. The strikes that began in July were in direct response to price rises and to shortages of food that have hit whole area of the country for months at a time. And these in turn were an aspect of an economic crisis that has been affecting all the East European countries.

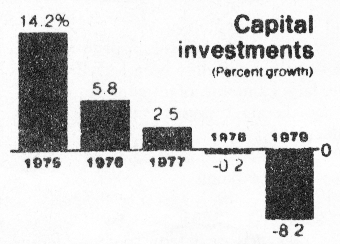

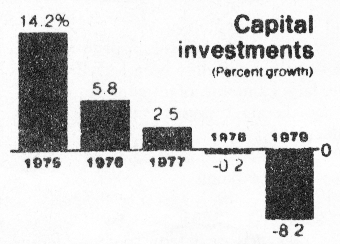

The scale of the economic crisis in Poland is shown by the accompanying block graphs. The rate of economic growth fell every year after 1976, until last year the national income fell – there was, crudely, a recession.

At the same time, Poland has been faced with mounting debts to Western banks. These had reached £8.2 billion by the end of last year, and 70 per cent of the receipts for goods Poland sells to the West go into servicing this debt. The point has been reached where the regime has to borrow over greater sums just to pay off past debts. Elsewhere in Eastern Europe the picture has not been quite as grim as in Poland. In Hungary last year actual economic growth was about one per cent (as against a plan target of 3–4 per cent); real incomes fell by 1–1½ per cent as price rises cut into wages. In Russia the growth rate, 2 per cent, was the lowest since World War Two, and there have been authenticated reports of acute shortages of meat and other foodstuffs in Russian cities. In East Germany, ‘the ambitious industrial targets announced in 1976 have all been reduced year by year’ (Financial Times, 31-7-80). In Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia real wages fell. And for the six East European Comecon countries together, the average growth rate last year was only two per cent.

Overall, the situation is one in which workers have been squeezed and resentments are high. It is also one in which the bureaucracies feel that they have to squeeze workers still more, by pushing up prices and cutting into ‘subsidies’.

Marx’s account of capitalist crisis focussed on two different aspects: the long term tendencies within capitalism which led to industrial stagnation and ever greater crises; and the short term factors that made the crises take on a cyclical form. On the one hand, he talked of the long term tendency of the rate of profit to fall, on the other of the way in which boom turned into slump and slump into boom.

The Eastern European economies have displayed both a long term trend towards stagnation, and short term crises when this trend becomes extremely acute.

The long term trend was already clear by the 1960s, as the following table shows:

[ No table here in printed text ]

Marx explained the trend towards stagnation for capitalism in terms of what he called ‘the rising organic compsition of capital’ – as the surplus value extracted from workers in the past is invested in ever greater quantities in new means of production, the ratio of total investment to the number of workers grows. But it is workers, not means of production that create new value. So the cost of investment grows much more rapidly than the new value – and consequently the profits – to be obtained from it. The rate of profit, Marx argued, would tend to decline. He saw this as driving capitalism into more and more intractable crises.

In the case of the East European economics there has certainly been a tendency for ever larger amounts of investment to be needed to create the same amounts of new value.

|

Growth of national income |

||

|---|---|---|

|

1951/4 |

1955/8 |

1959/63 |

|

0.373 |

0.335 |

0.201 |

|

Average increase in industrial production |

||

|---|---|---|

|

1951/5 |

1956/60 |

1961/5 |

|

6.4 |

5.1 |

4.7 |

The result of these trends was that by the beginning of the 1970s, the East European and Russian regimes had growth rates lower than some of the key western states with which they were competing (Japan, West Germany). They attempted to compensate by ploughing still more to the national income into investment: the proportion of industrial output taking the form of ‘producer goods’ (factories, machine tools and raw materials) grew from 70 per cent to 75 per cent in the USSR between 1950–55 and 1970, from 55 per cent to 61 per cent in Czechoslovakia, from 55 per cent to 65 per cent in Poland.

But such an increase could only be achieved by preventing real wages from rising as industrial production rose – indeed, in some cases cutting living standards as production rose. So for instance, in Poland where real wages had risen after the great strikes of 1956, they stagnated through the 1960’s. When in 1970 the government tried to cut them by raising meat prices Gierek, argued with workers:

‘We voted (at the party congress) for increasing living standards. These were ignored because it was not wished to annul certain decisions on investments which were very drawn out and had to be completed.’

On top of the long term trend, towards stagnation, the East European economies are subject to cyclical crises that have certain similarities with those in the West.

The fact of cyclical crises it has long been recognised by the more honest East European economists (even if most Western Marxists have chosen to ignore the matter): accounts of them have been provided, for example, by the Yugoslav Branko Horvat (Business Cycles in Yugoslavia) and the Czechs Goldman and Korba (Economic Growth in Czechoslovakia). These have pointed out that in the 1950s and 1960s the cycles were more marked than those in many Western countries.

The pattern goes like this. For two or three years those running the economies assume that they can achieve very fast rates of economic growth; vast new investments are undertaken, new construction sites proliferate and large numbers of new workers are taken on. Then it is suddenly discovered that the resources do not exist within the country to finish all these new investments. Some are abandoned for the time being (leading to a massive waste of potential wealth); some are finished by importing from abroad the necessary resources (so creating balance of payments deficits); some are finished by diverting to them goods which were meant for workers consumption (meaning that prices rise and/or consumer goods and basic foods disappear from the shops – in either case, real wages fall).

The fast rates of economic growth boasted of only months before give rise to very low, or even nil, rates of growth and a general sense of crisis. Promises made to workers of higher wages are replaced by wage controls, attempts to push up prices, the disappearance of basic goods from. shops, and continual calls for ‘realism’ and sacrifice’ from the regime.

As with the cynical crisis in the West, the Eastern crisis does not last forever. Eventually growth is resumed again (although’ as we have seen, at ever slower average rates). But this only leads those running the economy to dream of still more grandiose investments and to drive society towards the beginning of a further crisis.

These cyclical crises are important for two reasons.

First, they encourage chaos, inefficiency, waste and cynicism throughout society. The initial attempt to make the economy expand more quickly than can be achieved given existing resources is the opposite of real planning. When it is found that the exaggerated ‘plan targets cannot be met, the bureaucrats run round like lunatics, chopping and changing on a monthly a weekly or even a daily basis the goods which particular industries and plants are expected to produce. No-one, manager or worker, knows what they might be expected to produce at short notice, and deliberately conceal from those above them the resources available for production so as to give themselves leeway when the changes are announced. The result is the proliferation of inefficiency and wasted throughout the economy that is often noted by economists and even party leaders.

Second, the cynical way in which the symptoms of crisis appear means that the tensions in society grow very intense for a period, then seem to die down, only to re-emerge in a more intense form at a later stage.

A final point needs to be made in relation to the cyclical aspect of the crisis: its cause. The East European economists who have drawn attention to the crisis have not usually come to term with this. Yet it is not too difficult to locate.

All the East European economies are relatively small compared to their main competitors: the Polish shipbuilding industry is a midget compared to Japan; the Czechoslovak car industry is not in the same league as General Motors; even the whole Russian economy is smaller than the US with which it is in military competition. In order to survive in international economic and military competition, the industries of each East European state have to engage in a level of investment comparable to that of much bigger rivals, even if this is beyond what can really be sustained by the national economy. Hence the continual tendency for the over-ambitious plans that begin the cycle. The crises are a by-product of participating in a world capitalist economy. (For an elaboration of this argument, see my two articles, Poland and the Crisis of State Capitalism in IS (old series) 92 and 93.)

We have seen how the growth rates of the East European states had fallen to below the level of some of their Western competitors by 1970. The problem tended to be most severe for the relatively more advanced Eastern states. In Bulgaria, Rumania and Russia there tended then still to be some untapped reserves of raw materials and labour (in the countryside); things tended to be much tighter in Czechoslovakia (where economic crisis had already helped precipitate an acute political crisis in 1967–9), Hungary, East Germany and Poland. When Polish workers took the country to the edge of a general strike in 1970–71, it became clear of the rulers of these countries that any further attacks on living standards was very dangerous.

It was then that the Polish leaders, followed by the Hungarians and to a considerably lesser extent the Czechs, turned to the Western banks for a way out of their difficulties. They seem to have had unbounded belief in the ability of western capitalism to go on expanding indefinitely: they began borrowing on an ever-increasing scale to build vast new industries, on the assumption that there would be no difficulty in selling the products of these industries in the West a few years later. In this respect, they behaved just like any Western company that borrows from the banks to finance an expansion of output during a boom.

At the same time they bought off some of the discontent of the workers by allowing increases in living standards (although these were not nearly as high as often claimed). It was this that allowed the Polish leadership to get away with victimising in various ways many of the leaders of the strikes of 1970–71.

In the early and mid-70s Poland seemed to have achieved a new stability. Very high levels of economic growth were achieved, the bureaucracy gained new faith in itself, and the workers seemed contented.

But all this rested upon a trebling of imports from the West at a time when exports did not even double: the difference had to be paid for out of the loans.

When the Western economy went into a recession in 1973–4, it should have become clear to Poland’s rulers that they were not going to be able to pay off these loans to the West merely by selling the goods produced by the massive new investments. But for more than two years they did nothing, still believing that the Western crisis could not last long. Then in the summer of 1976 they tried to take the only remedial action that seemed open to them – they raised prices of basic goods. But once again they were faced with massive strikes that repression could not smash. And once again they had to rely on loans to get them out of their difficulty.

|

They were effectively gambling on a further western boom to solve their problems. It is this which has led them to the present impasse – an impasse that could be predicted back in 1976:

‘The result in 1978–9 could be catastrophic for the Polish bureaucracy. Many of their foreign loans will fall due just as internal inflationary pressures peak and world markets shrink. Then they will have to either turn on the workers still more viciously, risking a repetition of 19S6 and 1970, or suffer a full blown recession ...’ (Poland and the crisis of State Capitalism, op. cit.)

In fact, over the last 18 months they have tried both tactics at once. They have forced the economy into a recession last year and this, by postponing completion of many large investments that were only half finished and prevented industries getting basic goods they had been expecting from abroad; and they have tried to push through massive cuts in real wages.

The Polish bureaucracy is clearly suffering from the impact of the world economic crisis. This has helped push up material costs and interest charges for Polish industry at the same time as reducing the market for Polish goods. But the bureaucracy is not simply a victim of the world crisis. It is also one of the elements – just as any individual capitalist is – producing the crisis. In 1971–3 and 1977–9 Polish bureaucracy was among those scouring the world market for raw materials and loans, forcing up world prices and so precipitating the international crisis of 1973 and 1979. Like any other capitalist its reaction to a boom was to expand flat out, without even considering whether there were the resources to maintain such a rate of expansion or whether there would be markets left to dispose of the goods produced.

But that is not all. By its holding of workers living standards below the increase in total production, it has helped to contribute to the world wide discrepancy between the expanded scale of production and the narrow limits of consumption. By its slashing of investment in an effort to balance its books, it has made that discrepancy still greater. It has contributed to creating the very situation from which its exports suffer of too many goods chasing too little ‘demand’. It has been one element in the capitalist system internationally, and has helped cause all the symptoms of crisis from which it suffers.

The immediate economic situation gives the rulers of Poland less room for manoeuvre than in previous great crises. They are caught between the rival demands for resources arising from the need to complete huge, half finished investments, from the costs of servicing their overseas debts, and from the workers. The only ways they have of easing the pressures if they cannot cut workers’ living standards is to leave the unfinished investments as they are (thus abandoning economic growth for the time being and the production of further export goods to pay off their debts) and to beg still more from the bankers.

What applies to Poland applies – although not always to the same degree – to the other East European states. The more advanced industrially have increasingly turned towards the world economy to overcome their own problems over the last 20 years, in response to the long term trend to stagnation in their economies. But this has landed them with balance of payments deficits and debts that now confront them as urgent problems in their own right. The not-as-advanced industrially were able to proceed over the last 10 years without a great degree of integration with the West, and without the huge debts. But now these – especially the USSR – find themselves with the same low growth rates that afflicted Poland a decade ago. They also find that their own workers are unwilling to suffer cuts in living standards (witness the strikes in Russia’s autoplants). Yet for them the scale of the crisis in the West rules out any easy way out though further integration into the Western economies.

Such are the economic constraints – and very tight ones they are – within which the current social conflicts in Eastern Europe are being played out.

Does this mean there are no ways out for the East European regimes? Lenin once said there was no crisis which capitalism could not overcome if the working class missed its opportunity and gave the system a chance. This applies just as much to the East European state capitalisms today. If the working class fails in its defence of living standards and if the Western banks keep renewing their loans, then in a couple of years time things might start coming right for the Polish bureaucracy.

There are already a few isolated pointers as to what might happen. In recent months economic stagnation in Eastern Europe has reduced trade deficits with the West. As new very modern investments are completed, Polish exports might rise a little, even in glutted markets, because of the low wages of Polish workers.

However, none of this can take place unless the bureaucracy succeeds in disciplining the working class. Its strategy has been to divide and rule – to allow certain groups of workers to protect their living standards against the effects of crisis, while hitting Other groups of workers harder than ever. That is the logic behind the moves throughout Eastern Europe to replace food subsidies that aid everyone (at least, everyone who can push or bribe their way to the front of the queues) by general price rises combined with wage rises for selected workers. Then those who work in enterprises that are profitable by world standards will get something more than a bare subsistence wage, while those who work in other ways will sink down to living standards, even worse than those of the long term unemployed in the West. The ‘reserve army’ of the miserably paid will discipline the rest. If it can get away with some such scheme, then the bureaucracy will have been able, like the ruling classes in the West, to use the cyclical crisis to alleviate some of its long term problems.

However, any alleviation can only be temporary. Such measures will not stop the long term pressures causing the rate of growth to decline. Nor will they stop the ever greater integration of the East European economies, with their cyclical patterns of growth and stagnation, into the boom-slump world economy. And so they will not stop a recurrence, in four or five years time, of exactly the sort of crisis we are witnessing now, with all the social upheaval it can produce.

The point is important. If the Polish workers do not succeed in breaking through this time, that does not mean the struggle is over, however stable things might appear to be in a couple of years’ time.

But of course, it is by no means certain that the bureaucracy will even succeed in finding a way out of the impasse this time round. The workers have already shaken Polish society. Their actions may well prevent the Polish bureaucracy from resolving the crisis on its terms. And then, not only pierek, but Husak and Kadar and Brezhnev ... and Schmidt and Thatcher and Carter (or Reagan) will have cause to worry.

Last updated on 21 September 2019