From International Socialism 2 : 60, Autumn 1993, pp. 77–136.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

Eighty five percent of humanity live outside the advanced industrial countries. Any judgement about the future of capitalism is a judgement about what it does to them and how they respond. Twenty five years ago the economic orthodoxy was that capitalist market mechanisms could not bring about economic development in what was generally called the ‘Third World’. By contrast the command economies of the ‘socialist countries’ were seen as advancing without problems, regardless of the repressive political character of their regimes. As the staff of the World Bank now recall of ‘the dominant paradigm at that time’:

It was assumed that in the early stages of development markets could not be relied upon, and that the state would be able to direct the development process ... The success of state planning in achieving industrialisation in the Soviet Union (for so it was perceived) greatly influenced policy makers. The major development institutions (including the World Bank) supported these views with various degrees of enthusiasm. [1]

Just as Keynesianism was dominant within bourgeois economics in the advanced countries at the time, so statist, ‘import substitutionist’ doctrines were hegemonic when it came to the Third World. The main proponent of these in the 1940s and 1950s was the very influential United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America, directed by the Argentine economist Raul Prebisch. It argued that development could only take place if the state intervened to block imports from the advanced countries and to foster the growth of new local industries. [2] The market alone would only prolong stagnation and poverty. Proponents of anti-statist pure market theory existed, but their influence was marginal and they were very much on the defensive. So even a leading figure in the monetarist ‘Chicago school’, Harry Johnson, could accept in the 1960s that ‘in some cases the prospects for genuine economic growth are so bleak that nationalism is the only possible means for raising real incomes’. [3]

If these were the views of powerful defenders of the international bourgeoisie, it is hardly surprising that the common sense of the left became that capitalism was incompatible with economic advance in the Third World. The case was powerfully put by people like Paul Baran and Andre Gunder Frank. Baran argued:

Far from serving as an engine of economic expansion, of technological progress and social change, the capitalist order in these countries has represented a framework for economic stagnation, for archaic technology and for social backwardness ... [4]

The establishment of a socialist planned economy is the essential, indeed indispensable, condition for the attainment of economic and social progress in underdeveloped countries. [5]

Frank was just as adamant:

Short of liberation from this capitalist structure or the dissolution of the world capitalist system as a whole, the capitalist satellite countries, regions, localities and sectors are condemned to underdevelopment ...

No country which has been tied to the metropolis as a satellite through incorporation in the world capitalist system has achieved the rank of an economically developed country except by finally abandoning the capitalist system. [6]

‘Socialism’ for Baran and ‘breaking with capitalism’ for Frank meant following the model of Stalinist Russia. [7] But even those who opposed ‘socialism in one country’ from a revolutionary perspective accepted part of the argument. In a powerful article in 1971 Mike Kidron proved the incapacity of Stalinist state capitalism any longer to be able to develop backward economies – a proof well vindicated by subsequent developments in countries like Mozambique, Vietnam, and, above all, Kampuchea – and drew the conclusion that this meant there could be no development without a break with capitalism internationally. This was ‘the end of a terrible illusion, held as fervently by many seeming revolutionaries as by members of the more orthodox schools: that economic development in backward countries is possible without revolution in the developed ...” [8]

So pervasive was the view that ‘capitalism means underdevelopment’ that people read it back into some of the Marxist classics – despite arguments by Lenin and Trotsky to the contrary. Baran quoted Lenin to back up his case, while even someone as perceptive as Nigel Harris could write in 1980, ‘the Bolsheviks in 1917 believed the role of the national bourgeoisie was exhausted. In this context that means the bourgeoisie could no longer fulfil its “historic tasks”, namely the creation of capitalism’. [9]

The established view was not, however, long lasting. In the 1970s it was dealt heavy blows from two sides. On the one hand, the state directed model of economic development entered into crisis. In Asia the tightly regulated Chinese economy and the less tightly regulated, but still centrally directed, Indian economy both began to stagnate, forcing governments to look for alternatives; in Latin America the import substitutionist model was found wanting in its Argentine homeland as economic and political crises erupted; in Africa state direction could not break the vicious circle of underdevelopment, impoverishment, political corruption and dictatorship.

On the other hand, a number of countries which oriented themselves to the world market experienced very fast growth. In Asia four bastions of anti-Communism – South Korea, Kuomintang Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore – registered growth rates easily as large as those in Stalin’s USSR. In Latin America the generals who had seized power with an anti-reformist coup in Brazil in 1964 presided over a decade and a half of massive industrial expansion. And in Europe countries like Spain, Greece and Portugal, which Baran had included in the underdeveloped world, grew rapidly enough to join that rich man’s club, the European Community.

The intellectual pendulum swung from one extreme to another. Those bourgeois economists who had opposed the fashion for state direction now found support from among the best known of their old opponents, as the Chinese politburo, the Indian Congress leadership, the Argentine Peronists and most of the governments of Africa became overnight converts to the market. It was not long before Marxists were following in their footsteps. Bill Warren had led the way in 1978 with a work which portrayed imperialism as a progressive force, advancing the forces of production right across the world. He was followed by many others.

In Latin America there has been a ‘visible right turn of many of the left wing (social democrat, populist, socialist) parties, their political leaderships and their ideologues – the latter primarily ex-Marxist intellectuals of the 1960s.’ [10] Even Andre Gunder Frank now preaches the gospel of European unity and praises the pro-market policies of the Chinese government, claiming they amounted to ‘enormous strides in the ... economic and political direction’ barely days before the Tiananmen Square massacre. [11] By 1991 when the editor of New Left Review – once a fervent Third Worldist – proclaimed the indispensability of the market, he was simply expressing the new orthodoxy of a great swathe of the old left intelligentsia internationally. [12]

The central contentions of the new orthodoxy are summed up in the World Bank’s World Development Report 1991. It insists:

A consensus is gradually forming in favour of a ‘market friendly’ approach to development ... Competitive markets are the best way yet found for efficiently organising production and distribution of goods and services. Domestic and external competition provides the incentives that unleash entrepreneurship and technological progress ... If markets work well, and are allowed to, there can be substantial economic gain.

This does not mean that governments have no role. They ‘must, for example, invest in infrastructure and provide essential services for the poor’. But they should withdraw from productive activities and stop attempting to regulate international trade or the flow of investment. [13] Such views are not simply a matter of analysis. They also underlie the practical activities of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. When they are called on to help individual states with balance of payments or debt problems, they lay down as a precondition ‘stabilisation and structural adjustment programmes’ which implement the new orthodoxy. According to the orthodoxy, these are going to pay handsome dividends for the world’s peoples over the next decade:

The World Bank is forecasting a surge in developing countries’ growth rates over the next ten years, as a result of the often painful economic reforms they have undertaken. Growth in the developing world is projected at 4.7 percent a year over the period 1992–2002 compared to 2.7 percent in 1982–92. [14]

Similarly the IMF claims, ‘medium term economic prospects for the developing countries appear brighter than for decades.’ [15]

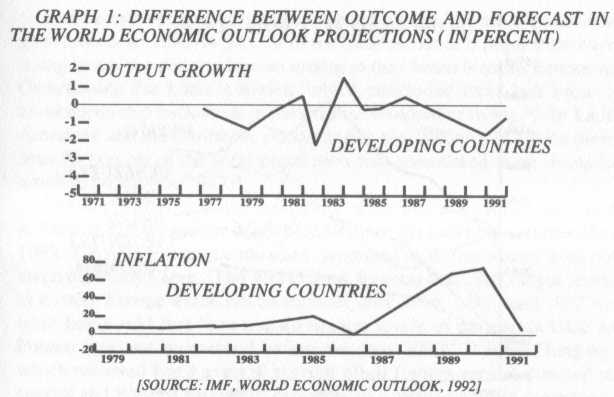

Such forecasts are repeatedly made, and just as repeatedly reported as ‘facts’ in the media, with headlines like ‘Bright outlook for Third World’ [16] or ‘India, reform pays off’. [17] Yet previous optimistic forecasts from the World Bank and the IMF have usually been way off beam, as graph 1 shows. Indeed, the World Development Report 1991 itself admits that ‘the 1980s were a difficult decade for most countries’. [18]

The latest report on the 47 least developed countries by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development says: ‘Per capita incomes in the very poorest developing countries have fallen for the past three years ...’ [19]

|

But it was not just the least developed countries that suffered in the 1980s. Virtually the whole of Africa has been undergoing a 20 year long decline.‘Per capita GDP fell from $854 in 1978 to $565 in 1988; external debt rose from $48 billion to $423 billion ...’ [20] And devastation has even hit economies which were presented as the success stories of the 1970s. Nigeria’s industrial output fell by an average of 2.1 percent a year through the 1980s and private consumption per head by 4.8 percent a year – both had risen substantially in the 1960s and 1970s. [21] ‘Development’ has not stopped most people’s living standards falling to the same level they were at more than 30 years ago.

Nigeria might be thought of as an exception, since its fortunes were tied to its oil revenues, which declined with the fall in the oil price in the 1980s. But things have been no better in the Ivory Coast, ‘for a time the darling of the development agencies as its outward-looking policies generated growth. So strong was the economy in 1979 that one large multinational made 10 percent of its worldwide profits there’. [22] In the 1980s industrial output fell by 1.7 percent per year while foreign debt rose to $15 billion and the cost of servicing it to 40 percent of export earnings. [23] The real income of urban workers fell by 20 percent between 1978 and 1985, before ‘a new fall in the terms of trade brought the country back into recession and financial crisis’. [24]

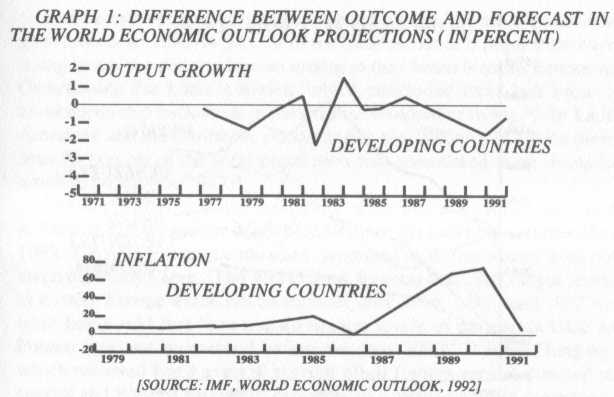

Latin America – which contained by far the biggest of the ‘newly industrialising countries’ of the 1970s – suffered from massive crises through the 1980s, as can be seen from graph 2. There was a fall in GNP per person for the whole of Latin America of over 10 percent between 1980 and 1990. [25] Table 1 shows how accumulation proceeded at a much slower rate in the 1980s than in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

|

|

Table 1: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

(Annual average compound growth rates) |

||

|

|

1950–73 |

1973–80 |

1980–89 |

|

Argentina |

4.53 |

4.50 |

1.08 |

|

Brazil |

9.44 |

11.17 |

5.29 |

|

Chile |

4.21 |

2.34 |

1.88 |

|

Colombia |

3.79 |

5.14 |

4.80 |

|

Mexico |

7.14 |

7.38 |

4.20 |

|

Venezuela |

7.59 |

8.08 |

3.23 |

|

Arithmetic average |

6.12 |

6.44 |

3.41 |

|

(Source: A.A. Hoffman: Capital Accumulation in Latin America) |

|||

Some 76 countries implemented ‘adjustment programmes’ designed by the World Bank on ‘free market’ criteria in the 1980s. [26] Only a handful had better growth or inflation rates than in previous decades; of 19 countries which carried through ‘intense adjustment’, only four ‘consistently improved their performance in the 1980s.’ [26] In capitalism’s own terms the system was much less successful than it had once been.

For the mass of people living within the system the picture has been grim indeed. In 1990 44 percent of the Latin America’s population were living below the poverty line according to the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America, which concluded there had been ‘a tremendous step backwards in the material standard of living of the Latin American and the Caribbean population in the 1980s’. [27] In Africa more than 55 percent of the rural population was considered to be living in absolute poverty by 1987. [28]

Just as devastating to the pro-market argument is what has happened in Eastern Europe and the former USSR since the turn to the market after 1989. The new ‘economic miracles’ promised by the reformers have not taken place anywhere. ‘The World Bank forecast that 1989 output levels in Eastern Europe would not be regained until 1996 ... By April 1992 we were being told that “pre-transformation levels of per capita GDP in Poland may not be reached before the year 2000”.’ [29] Even Hungary, which received ‘well over 50 percent of all foreign capital directed to central and Eastern Europe’ [30], experienced a quadrupling of unemployment to 9 percent in 1991 and was expected to see that double in 1992. [31]

If attention is focused on Africa, Latin America, Eastern Europe or, for that matter, the Middle East, then the conclusion has to be that only in rare and exceptional circumstances does the market succeed in restoring the old dynamic of capital accumulation, let alone lead to any improvement in the economic position of the majority of people. None of this has prevented proponents of ‘free market’ solutions to the world’s ills claiming that their remedies can work. They insist that if, for instance, none of the eight economic ‘stabilisation’ programmes in Brazil in the last dozen years have been successful it is because impediments to the market have remained as a result of governments failing to push reform programmes through to the end.

They have also seized upon any year on year improvement in output anywhere as proof that their remedies are succeeding – as with Poland’s 1 percent industrial growth in 1992 (after a 37 percent fall in the previous three years) or the upturn in Chile’s economy in the early 1990s. But their central argument has been to point to East Asia and important parts of South Asia. The World Development Report 1991 speaks of ‘the remarkable achievements of the East Asian economies’, of ‘various degrees of reform’ in China, India, Indonesia and Korea being ‘followed by improvements in economic performance’. [32] Samuel Brittan, of the Financial Times, has reassured his readers:

Someone who wants to cheer up should look, not backwards to the Great Depression, but to the developing countries of Eastern Asia which have contracted out of the world slowdown ... The four Asian ‘tigers’ are all estimatedto be growing by between 6 and 7.5 percent this year. Even the non-tiger countries have achieved a comparable performance. [33]

There certainly has been growth in these countries, both absolutely and in terms of output per head:

|

Table 2: |

|||||

|

|

|

1980–89 |

1965–89 |

||

|

|

GNP |

|

Industry |

GNP per head |

|

|

South Korea |

9.7 |

12.4 |

7.0 |

||

|

Hong Kong |

7.1 |

n/a |

6.3 |

||

|

Singapore |

6.1 |

5.0 |

7.0 |

||

|

Thailand |

7.0 |

8.1 |

4.2 |

||

|

Malaysia |

4.9 |

6.5 |

4.0 |

||

|

Indonesia |

5.3 |

5.3 |

4.4 |

||

|

China |

9.7 |

12.6 |

5.7 |

||

|

India |

5.3 |

6.9 |

1.8 |

||

And the advantages of growth have not always been confined purely to the ruling classes in these countries. It makes no sense at all to talk of South Korea today as having ‘Third World living standards’. Real wages are probably between two thirds and three quarters of those in Britain [35] (although the average working week, at 47.4 hours [36], is substantially longer than in Western Europe and North America). In the early 1990s there were fewer beggars on the streets of Seoul than there are on the streets of London.

In China a surge of agricultural output [37] has increased the average food supply per head, raising it from under 2,000 calories a day (less than the minimum nutritional requirement) in the late 1970s to over 2,500 calories in the late 1980s (well above it). This is certainly an advance for a country where previously the great mass of people lived in a condition of near hunger, and stands in marked contrast to what has happened in, say, sub-Saharan Africa – where the daily calorie supply is 9 percent below minimum requirements and less than 25 years ago. [38] The advance is not only quantitative. There has also been an improvement in the average diet. For most people food does not any longer mean just rice, and consumption of pork, fish and vegetables has risen considerably. [39]

At the same time, many families now own consumer goods they could only dream about in the past. In 1978 only about one family in four had a radio or bicycle, let alone a TV or washing machine. [40] By 1989 most families in the cities owned a television (40 percent of them colour TVs), a bicycle and an electric fan, while two thirds had a washing machine and a sewing machine, and one in three had a fridge. [41] And even among the much poorer peasantry there was an average of a bicycle for every household, a sewing machine and a radio for half of them, and electric fans and TVs (nine times out of ten black and white) for more than a third. [42]

No wonder that pro-capitalist commentators look with hope at the East Asian economies, believing they will inexorably continue to expand. No wonder too that they fantasise about what the world would be like if only the ‘startling success could be replicated elsewhere’:

Billions of people in developing and formerly Communist countries could look forward to improved living standards. And the hope, eventually, of eliminating the scourge of grinding poverty would seem less quixotic. [43]

Yet there must be very serious doubts both about the likelihood of the East and South Asian economies continuing to grow through the 1990s as they did in the 1980s and about the possibility of their example being generalised to the rest of the underdeveloped world.

If the old ‘development of underdevelopment’ view was wrong to claim that capitalism could never develop any fresh parts of the globe, the new pro-market orthodoxy is absolutely mistaken in its belief that development will occur if only obstacles to the ‘free market’ are removed. When capitalist production using waged labour begins to take root anywhere there is at least some degree of accumulation, of the transformation of living labour into means of production, and therefore ‘development’. But the new capitals cannot avoid competition with the much larger capitals which already exist elsewhere in the world system. And so, just as the productive power of a certain region grows, it is subjected to the dynamic of the wider system – the booms and slumps, the spells of frenzied accumulation of capital and the spells of dizzy destruction of capital, the national rivalries and the wars.

Classical Marxism always understood the contradictory character of such development. It understood that the first effect of Western capitalism forcibly opening up colonies to the world system was often not economic advance, but regression as the old ways of producing wealth were destroyed and little put in their place – as with the destruction of the old Inca and Aztec civilisations in Latin America, the slave trade in Africa, the pillaging of Bengal by the British. [44] What is more, the colonial powers often then sought to maintain their rule through alliances with wasteful, unproductive and parasitic groups among the colonised population – as with the ties the British authorities established with the zamindar landlords and the rulers of the princely states in India.

But that was never the whole story. By destroying the old societies, the Western powers made room for capitalist exploitation and, therefore, accumulation. The process was often very slow (as was the original development of capitalism out of the feudal system in parts of Europe). Colonial rulers could obstruct it when it contradicted their own looting or alliances with privileged parasitic classes. But they could not stop it completely. There was a market for luxury goods among both the Western colonists and the old parasitic groups, and there were profits to be made by organising production for this market using wage labour. Some members of old indigenous merchant and artisan classes began to see this and to undertake production on a new basis, while some Western capitalists saw advantages in adding surplus value from production in the colonies to what they got from production in the advanced countries. As capitalist production began its slow advance, it in turn created a market, albeit at first a small one, for the basic means of consumption (bread, lodgings, clothing) among a new class of urban workers.

Over time the growth of such markets was bound to persuade some farmers, and occasionally some landowners, to turn to elementary forms of capitalist agriculture. As Marx wrote of the impact of British colonialism in India:

England has a double mission in India: one destructive, the other regenerating – the annihilation of old Asiatic society and the laying of the material foundations of Western society in Asia ...

The historic pages of their rule in India hardly report anything beyond the destruction. The work of regeneration hardly transpires through a heap of ruins. Nevertheless it has begun ... [45]

He pointed out that even though the British cotton manufacturers only wanted railways in India to extract raw materials:

When you have introduced machinery into the locomotion of a country which possesses iron and coal you are unable to withhold it from fabrication. You cannot maintain a net of railways over an immense country without introducing all those industrial processes necessary to meet the immediate and current needs of railway locomotion, and out of which there must grow the application of machinery in those branches of industry not immediately connected with railways. The railway system will become, in India, truly the forerunner of modern industry. [46]

This did not, however, lead him to believe that Indians should simply submit to colonialism. He understood only too well that capitals based in Britain would use their political influence over the colonising state to hinder the advance of rivals in India:

The Indians will not reap the new elements of society scattered among them by the British bourgeoisie till in Great Britain itself the now ruling classes shall have been supplanted by the industrial proletariat or till the Hindus themselves have grown strong enough to throw off the English yoke altogether. [47]

Lenin’s Imperialism assumed capital would flow from the advanced countries to the less advanced: ‘The export of capitalism greatly affects and accelerates the development of capitalism in those countries to which it is exported ...’ [48] But he too saw this was not the end of the matter. Such a growth of capitalism also drew the backward countries into the economic crises and the disastrous wars that beset the old capitalisms. Trotsky spelt all these arguments out in much greater detail in 1928, when polemicising against Stalin and Bukharin:

Capitalism inherently and constantly aims at economic expansion, at the penetration of new territories, the surmounting of economic differences, the conversion of self sufficient provincial and national economies into a system of financial inter-relationships. Thereby it brings about their rapprochement and equalises the economic and cultural levels of the most advanced and most backward countries. Without this main process, it would be impossible to conceive ... the diminishing gap between India and Britain ... [49]

Writing of Kuomintang China, Trotsky referred to ‘the extraordinary rapid growth of home industry on the basis of the all embracing role of mercantile and bank capital; the complete dependence of the most important agrarian districts on the market; the all-sided subordination of the Chinese village to the city – all these bespeak of the unconditional predominance, the direct domination of capitalist relations in China’. [50] His account – which foreshadowed the conclusions of recent studies of 1920s China [51] – stands in sharp contrast to Baran’s claim that ‘a republic of the Kuomintang variety ... has nothing to hope for from the rise of industrial capitalism ...’ [52] But Trotsky also insisted that the world system necessarily reacted on the underdeveloped world in negative as well as positive ways:

By drawing countries economically closer to one another and levelling out their stages of development, capitalism operates by methods of its own, that is to say, by anarchistic methods which constantly undermine its own work, set one country against another, one branch of industry against another, developing some parts of the world economy while hampering and throwing back the development of others ... Imperialism ... attains this ‘goal’ by such antagonistic methods, such tiger leaps and such raids upon backward countries and areas that the unification and levelling of world economy which it has effected is upset by it even more violently and convulsively than in the preceding epoch. [53]

The interaction of domestic capital accumulation and the world system has led to a number of stages of capitalist development. The first Third World capitalists faced some obstacles which their forebears in Europe had not. They usually began by exploiting wage labour in industry and accumulating on a small scale, as do most new capitalists. Yet they faced competition from the goods produced by established Western capitalists operating with relatively large capitals. The new industries which they established therefore often led a very precarious existence, as do those anywhere owned by small capitalists. Even when they discovered new markets or new products, they could find they acted as little more than pathfinders for bigger, Western, capitalists who would then enter the new line of business and drive them out. What is more, these competitors had political influence over the colonial state and would use that influence, when necessary, to help them succeed against the newcomers.

The new capitalists found the dice loaded against them. And there could be a vicious circle of underdevelopment. Every failure in one sector of the economy reduced the markets available for local capitalists setting up in other sectors. Industrial stagnation, or even regression, could easily become the norm as the old mode of production was destroyed and the new one was unable to take root. This was the particle of truth in the old ‘development of underdevelopment’ theory.

But there were occasions when industrial development did take off. And the failures were not because capitalism automatically favours the ‘metropolis’ and causes the ‘periphery’ to stagnate. Rather it was because particular established capitalist interests were in a position to keep out new rivals. Historically, the first big spurt of industrial development in places like India and China took place during the First World War, when the disruption of much foreign trade suddenly freed indigenous industries from more advanced competition.

In many countries the progress continued until the early 1930s when the great slump in the advanced counties suddenly destroyed much of the market for foodstuffs and other raw materials, caused a huge drop in Third World incomes and threw whole economies backwards. Faced with the danger of immense social turmoil and unable to balance their own books, some governments, particularly in Latin America, reacted pragmatically by trying to cut themselves off from external destabilising pressures. They imposed very tight controls on imports, refused to repay foreign debts and used the power of the state to redirect resources from some industries to others. These measures had the effect of recreating the situation that had been created by accident during the First World War, enabling local industrial enterprises to expand without fear of competition from more advanced firms abroad. Within a couple of years of the adoption of the new measures, the local economies moved from slump to boom.

It was an example which was widely followed in the first two decades after the war. ‘Import substitutionism’ – and with it varying degrees of state capitalism – became the norm not merely for Latin America but for newly decolonised countries like those of South Asia and Africa, and for the East Asian states of South Korea and Taiwan. For a number of years the policy seemed to work. ‘The data show considerable advances were made in the degree of industrialisation’ [54]; ‘the performance of all developing countries actually improved between the 1950s and the 1960s’. [55]

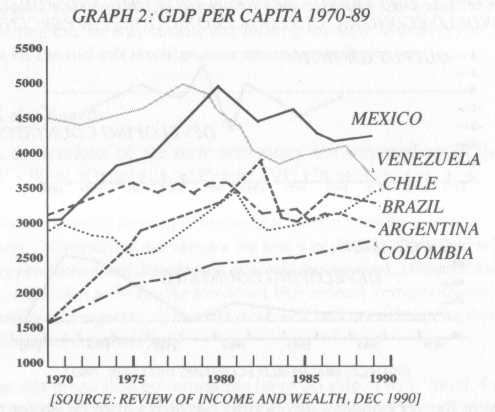

But in the late 1960s changes in the wider world system began to throw the strategy into crisis. Agricultural advance and increased industrial efficiency in the developed countries reduced their dependence on raw materials, Third World commodity prices fell (except for a brief upward surge in 1973–4), as graph 3 shows, and with them the export earnings needed to pay for the industrialisation drives.

|

It was then that, more by luck than by judgement, a number of states stumbled upon another development strategy, directing resources into certain industries which found niches for exporting manufactured goods to the advanced countries. This was, for instance, the path South Korea began to follow after the establishment of the Park dictatorship in the early 1960s and Brazil after the military coup of 1964.

Not all the Third World states could follow the new ‘export oriented strategy’ at the time. In some the state was not powerful enough to divert resources from old landowning classes to industry of any sort: significantly, the successful Asian NICs were either city states (Hong Kong and Singapore) without a landowning class, or countries where the military had been prepared to carry through a radical land reform in order to strengthen its own position (Taiwan and South Korea). In some the import substitutionist stage had simply not built up industry sufficiently to compete internationally. In some the opposition of those industrialists who had benefited from import substitutionism prevented a different approach. In any case, if all the Third World states had hunted for ‘niches’ there would not have been enough to go round! But none of this stopped ruling classes, and their ideologists, who not so long before had extolled ‘import substitutionist development’, now opting for the free market and the ‘export oriented model’.

The most widespread form of the pro-market ideology is what is often called ‘neo-liberalism’ – the word ‘liberal’ not being used in its normal Anglo-Saxon sense of ‘vaguely progressive’, but rather to refer to the ideal of an economy with minimal state controls on business activities. It is the set of ideas common to Thatcher and Reagan, Pinochet and Menem, Klaus and Yelstin, and the leaders of the Baltic states, Poland, the Czech republic and Hungary. And it underlies the various World Bank ‘adjustment programmes’ which debtor states have to accept if they are to receive International Monetary Fund support.

At the centre of the neo-liberal view is the contention that the state should withdraw from direct economic activity. Its role is to facilitate the free play of the market, not to intervene in the market and still less to undertake productive activities on its own. The prevalence of these ideas today has led some Marxists, in this country notably Nigel Harris, to conclude that we are in a new period of capitalism, in which the members of an increasingly international capitalist class no longer need to root themselves in rival national state machines. The era of state capitalism and, by implication, imperialism, is at an end.

But the reality of the capitalist world is very different to the neoliberal ideology. The state still plays a mediating role between the local economy and the wider system, seeking to exert pressure to prise open foreign markets for local products, to mobilise local resources to take advantage of these markets and to entice multinational capital to set up shop in one country rather than another. In the process, the state’s role can be as great, even if differently exercised, as in the previous period of import substitutionism.

A recent important study of the interactions of multinationals and states by Stopford and Strange has concluded:

Growing interdependence now means that the rivalry between states and the rivalry between firms for a secure place in the world economy has become much fiercer, much more intense. As a result, firms have become more involved with governments and governments have come to realise their increased dependence on the scarce resources controlled by firms. [56]

The rulers of states need to maximise the resources at their own disposal if they are to buy support from a section of the population and ward off challenges from below. Increasingly, they can only do so if they can reach a bargain with the multinationals about the development of new means of production. But there is no easy way to achieve this goal. The neo-liberal doctrine of simply abandoning all government constraints on trade and opening up the economy to any multinational which wants to operate in it does not offer any guarantees of success.

Neo-liberalism assumes that the reforms will attract investment from firms which in turn will lead to stable economic expansion. But the reality can be very different to this. As Stopford and Strange note:

As firms harness the power of new technology to create systems of activity linked directly across borders, so they increasingly concentrate on those territories offering the greatest potential for recovering their investment. Moreover, in a growing number of key sectors, the basis of competition is shifting to emphasising product quality, not just costs. Attractive sites for new investment are increasingly those supplying skilled workers and efficient infrastructures ... [57]

These problems are most felt in the poorest regions of the world, especially Africa. However much they dismantle their old, protectionist, import substitutionist policies, they still remain unattractive to the multinational they want to woo: ‘Small, poor countries face increased barriers to entry in industries most subject to the global forces of competition’. The result is that ‘small, poorer countries cannot afford the luxury of letting market forces determine outcomes’. [58]

These countries are, in fact, usually in a no win situation. Import substitutionism was never going to be a successful option for them because of their limited internal markets. But the chances of breaking through with the export oriented strategy are little greater, despite all the admonishments from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. For they have little to offer multinational investors apart from cheap labour, yet many competitors offer the same. Even when they persuade multinationals to invest, such states rarely have the clout to prevent them changing their mind and moving elsewhere.

The multinationals are themselves subject to global competition, which is continually making them reassess their own priorities. They will invest in a particular country in order to open up certain markets – but then see the possibility of even bigger markets if they switch their investment elsewhere. What were enclaves of growth in a Third World country can suddenly become abandoned ghettos of decay. And there may be very little the governments of poor countries can do about it.

Hong Kong and Singapore, long established trading centres with favourable locations and very good international communications, stand almost completely alone in the world as the only small states to industrialise. Elsewhere the experience has been that of the central American republics, the great majority of Caribbean islands and of almost all of Africa – of limited growth during the world boom of the 1950s giving way to stagnation, and now often decline. No wonder even the World Bank can complain that ‘the results of market reforms have often proved disappointing in the developing economies.’ [59]

The neo-liberal ideology justifies itself by referring to the rise of the NICs. Yet the NICs themselves (except for Hong Kong) have not followed neo-liberal policies. Capitalist development has depended upon powerful state intervention in the economy, which continued even after an initial phase of import substitutionism gave way to the export oriented strategy. It was usually the state that marshalled the resources to enable locally controlled industry to conquer international markets, even if as a partner of multinationals or local conglomerates. Such was the approach, for example, of Brazil during the 1970s, when it was widely said to enjoy an ‘economic miracle’. It was also what happened in the large Asian NICs of South Korea and Taiwan right through the 1970s and 1980s. [60] Thus, even after South Korea had embarked on its export oriented strategy, the state, under the military dictator Park Chung Hee, insisted on restricting foreign capital to less than 50 percent ownership of joint companies, pushed through a policy of building up heavy industry in the face of resistance from both foreign and domestic capital, and controlled prices in such a way as to rig the market to achieve the sort of growth it wanted. [61] As one account sums up the experience of South Korea:

While mouthing anti-communist, anti-socialist free market slogans, it set out in practice to protect its domestic market and created one of the world’s most stringent foreign investment regimes. While receiving massive amounts of IMF and World Bank assistance, as a preferred anti-Communist client, the state launched, in the face of opposition from the two agencies, the heavy and chemical industry drive that spurred the creation of a more solid heavy and intermediate industrial base. One cannot say that the Korean state was lacking in either the vision or the will to create a more independent national industrial economy ... [62]

An internal World Bank memo notes that South Korea has followed policies very different to the neo-liberalism the Bank itself encourages:

From the early 1960s the government carefully planned and orchestrated the country’s development ... It used the financial sector to steer credits to preferred sectors and promoted individual firms to achieve national objectives ... It socialised risk, created large conglomerates (chaebols), created state enterprises when necessary and moulded a public-private partnership that rivalled Japan’s. [63]

Apparently, even some World Bank officials believe a study of the functioning of the East Asian economies will enable them to draw up ‘a new paradigm for development in the 1990s’, which does more than ‘just abdicate development to the private sector’. [64] However, if neo-liberalism provides little guarantee of development through establishing a certain territory as a permanent base for capital which wants to compete internationally, neither does state intervention. The inadequacies of both were shown dramatically by what happened to the one time ‘miracle’ economies of Latin America in the 1980s.

There was a time in the 1970s when the financial press assured its readers Brazil was the great rising Third World country whose industries were destined to challenge those of the West. The country had indeed experienced a decade and a half of amazing growth:

For almost 15 years (1965–80) the average rate of growth was 8.5 percent, making Brazil the fourth fastest growing country. This growth performance was reached by a modernisation strategy based on production of durable goods with up to date technology thanks to favourable policies towards imports and foreign investors and the massive penetration of foreign multinational companies ... [65]

The growth seemed even more impressive when it continued after the outbreak of the 1973 oil crisis and the world recession that followed. Under the Geisel military government of 1974–9 there were ‘moderate levels of inflation, real wage growth, and uneven but relatively high rates of output growth’. [66] Other Latin American states began to emulate the Brazilian policy. The military coups in Chile (1973) and Argentina (1976) were followed by an opening to external capital, in the hope that this would produce stable, export led growth. And again the outcome seemed encouraging, at first. Under the Videla regime in Argentina ‘the rate of inflation was lowered, real output grew, and a current account surplus was generated’, [67] while Chile’s real GDP grew 8.5 percent a year between 1977 and 1980. [68]

All this growth depended on foreign borrowing: ‘Many Latin American countries gambled on ambitious growth targets by borrowing heavily in international financial markets ... The external debt of Chile and Argentina almost trebled over a few years, 1978 to 1981 ...’ [69] But this did not seem to matter at the time – either to the national governments or the international banking system:

Up to the second oil price shock (1979–80) the gamble was worth taking.

Export growth was sustained in world markets at favourable prices ... as a consequence the ratio of debt outstanding to export proceeds was more favourable for all non-oil developing countries in 1979 than in 1970–72. [70]

This approach was later attacked on all sides as a ‘short sighted’ bungle by incompetent governments. But at the time the great majority of establishment economic commentators viewed things very differently. They spoke of the Brazilian and Chilean economic ‘miracles’ and dismissed fears of indebtedness. The IMF assured people in 1980: ‘During the 1970s ... a generalised debt management problem was avoided ... and the outlook for the immediate future does not give cause for alarm.’ [71] This was written just months before the second international recession, of the early 1980s, caught all these states unprepared. As export markets shrank and international interest rates began to rise, the debts they had incurred in the 1970s crippled their growth, threw them into recession and crippled their economies right through the 1980s.

In the aftermath of the debt crisis, the neo-liberal orthodoxy put all the blame on the state taking investment decisions rather than leaving them to private entrepreneurs ‘more responsive to market signals’. The state, it was said, was bound to be pressurised by vested interests (corrupt politicians, particular local capitalists, militant workers) into making inept and wasteful decisions. But that cannot explain the scale of miscalculation, for it occurred not just in Brazil, with a high level of state intervention in its economy, but also in Chile, which after the 1973 coup was the world pioneer in privatisation and neo-liberal economic policy. There the borrowing was by banking ‘groups’ controlling the newly privatised firms. The state was careful not to provide official guarantees for foreign loans equal to 14.5 percent of GDP and 66 percent of gross domestic investment by 1981. [72] ‘It was thought at the time by the economic authorities and some other observers that since most of the debt had been contracted by the private sector, the increase in foreign indebtedness did not represent a threat to the country as a whole’. [73]

But when the ‘groups’ proved unable to pay their debts, the international banks insisted that the Chilean dictatorship take responsibility for them. ‘The government “nationalised” large private debts that could not be serviced or repaid’. [74] Those who had made fortunes during the previous boom hung on to them, while the mass of the population suffered as unemployment rose to over 26 percent, and the government forced down real wages and per head welfare spending by 20 percent. [75]

In Argentina, Mexico and Uruguay private interests and corrupt political forces were equally involved in the build up of debt. While governments exerted themselves to persuade the international banking system to lend money, private capitalist interests put much of their effort into moving their funds abroad. [76] Again, however, it was the mass of the population who were expected by governments and neo-liberal advisers alike to pay the cost: in Mexico in 1987 real wages were only 43 percent and a ‘composite welfare index’ only 68 percent of the 1980 level. [77]

Whether the original borrowing had taken place under state auspices or private auspices, the result was the same. The major Latin American states were faced with external debt repayments ‘twice as large as Germany’s war reparations’ [78] after the First World War, leading to a massive outflow of economic resources. Yet by the end of the decade many of the countries were still as indebted as at the beginning, with the cost of servicing the debt eating up, on average, about a third of export earnings. [79]

The fact that the gambling, whether by private or state interests, went disastrously wrong should really surprise no one. ‘Private’ multinational financial and industrial corporations are just as capable of making catastrophic errors of judgement as are nation states – as is shown by the bankruptcy of Pan Am, Maxwell Communications Corporation and BCCI, and by the catastrophic losses incurred recently by General Motors and IBM. The mistakes are made because both states and private corporations are players in an international system which is increasingly unpredictable, so that what seems sound policy today turns to complete folly tomorrow.

Occasionally staunch defenders of the system admit this. So Jeffrey Sachs, the arch-adviser to governments implementing IMF-World Bank adjustment programmes, even today defends the gamble made by the Brazilian generals when they went on their borrowing spree 20 years ago: ‘The accumulation of Brazilian debt up until 1981 made good sense ... It was the unforeseen and essentially unforeseeable shifts in the world macro-economy that ultimately undermined Brazil’s strategy of debt accumulation.’ [80] This does not, of course, lead Sachs to challenge the essential features of the ‘world macro-economy’. But then it is not economic advisers but the mass of workers and peasants who pay with their living standards, and often their lives, for mistaken gambles in the world economic casino.

Sachs and his ilk have certainly not abandoned their view that such gambling is sound economic policy. In recent months the neo-liberal ideologists have once again begun to talk of a Latin American ‘miracle’, claiming that new bursts of growth prove how worthwhile were the ‘reforms’ of the 1970s and 1980s. Thus the Financial Times, commenting on a World Bank report [81], speaks of ‘the emergence of Latin America, phoenix like, from the ashes of the commercial bank debt crisis of the early 1980s’ with ‘the chance of joining east Asia as a second engine of developing country growth.’ [82] Mexico and Argentina are praised, and the ‘success’ of the Menem programme in Argentina is contrasted with the ‘failure’ of Brazil. [83] But Chile gets the highest honours, its former military government being credited with laying the basis for a ‘true breakthrough’ which meant ‘its economy expanded 10.4 percent last year, while inflation fell to 12 percent.’ [84]

But a long term overview of the Chilean economy makes the recent growth look much less miraculous. GNP per head was, after all, lower at the beginning of 1988 than it had been in 1971. [85] So the growth of 30 percent or more in the last four years has not even made up for lost time. What is more, the growth is precarious, depending, as in the late 1970s, on a massive inflow of private capital, much of which has gone into financing a boom in speculation and luxury consumption. In 1990 an attempt to contain the boom led to virtually nil growth in manufacturing industry [86], while, with the revival of the boom in 1992, ‘commerce grew fastest, showing growth of 14.3 percent, mainly because of higher imports ... Imports grew 22.2 percent, while exports grew by 12.3 percent.’ [87] In its more sober moments, even the World Bank has had to admit the inbuilt weaknesses of this sort of boom in an economy where servicing past foreign debts still eats up nearly 30 percent of export earnings [88]: ‘The 1980s demonstrated Chile’s sensitivity to external shocks. Projections suggest that Chile will require annual private capital inflows equivalent to approximately 3.5 percent of GDP ... There is a risk such inflows might not be forthcoming.’ [89]

Chile is the best case for the pro-market argument. The situation with Argentina and Mexico is even worse. In Argentina GNP per head and real manufacturing earnings were lower in 1989 than in 1965 [90], while the World Bank admitted in 1992 that the recent much acclaimed ‘recovery’ depended on ‘consumption growth fuelled by credit growth’ and that ‘imports have more than doubled’. [91] By May 1993, as imports surged until they were nearly 50 percent higher than exports [92], the Financial Times could note that ‘alarm is growing over Argentina’s increasing reliance on foreign capital’. [93] In Mexico the ‘boom’ meant that GDP in 1992 was only about the same as in 1981 [94], but it was enough to raise imports until they were about 80 percent higher than exports and to cause ‘the Mexican government of president Carlos Salinas, once proud of its free trade credentials’, to take ‘a series of measures to curb imports and to protect some of the country’s most inefficient industries’. [95]

The ‘booms’ have been accompanied by an end of the decade long flow of capital out of Latin America. Foreign direct investment climbed by 50 percent in two years to $38 billion in 1992, with portfolio investment growing even more explosively to $34 billion ...’ [96] The Financial Times says, ‘Latin America is once again in the enthusiastic embrace of the world’s financiers’. [97] The inward movement of capital does not, however, begin yet to compare with the drain out of the continent in the 1980s (according to one estimate, profit remittances and interest payments for the years 1982–9 totalled $281 billion [98]) and ‘in most countries these inflows are smaller in comparison with the size of the economies than they were in the 1970s’. [99] What is more, past debt still remains an enormous burden. The IMF has noted for Brazil, Chile, Mexico and Venezuela ‘the total interest burden was greater in 1990–92 than in 1978–82’. [100]

Most important of all, the inflow of capital can lead to great instability, to a rerun of the pattern of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The IMF itself notes the flow of capital has been motivated mainly by the search for quick profit rather than long term investment and warns:

The history of private financing flows to developing countries has been marked by repeated episodes of lending surges followed by market correction, debt servicing difficulties and curtailment of market access ... Volatility in external financing flows cannot be avoided entirely ... Integration into international capital markets necessarily implies exposure to the shifts in global market conditions ... Levels of debt are still relatively high, and there are questions about the adequacy of risk assessment by the new investors ... [101]

In fact, there are enormous risks in any economic strategy based on attracting private investment to finance an import-based boom. What is involved is exactly the same gambling over the direction of the world economy that led to such disaster in the early 1980s. Indeed, the risks are greater now.

The IMF explains that ‘strong ... net capital inflows ... have reflected a decline in the interest rates in industrial countries’. These relatively low interest rates are a product of the world recession. Yet the World Bank’s chief economist has admitted that its much headlined optimism about developing countries’ growth was:

heavily reliant on the assumption that the recovery that now appeared to be consolidating itself in the US would spread to the rest of the G7 industrial nations, with a prospect of sustained growth in the developed world over the medium term, combined with lower real interest rates. The forecasts also assume faster growth in world trade, a stabilisation in real non-oil commodity prices and continuations of policy improvements, especially in Latin America ... A more pessimistic set of assumptions would halve the rate at which developing countries’ per capita income grows. [102]

In reality, the Latin American economies are in a double bind. If the world economy recovers from recession, interest rates internationally will rise, and Latin America will no longer be so attractive to investors looking for a quick profit. But if the world economy does not recover, Latin American exports are unlikely to grow sufficiently to make balance of payments figures look healthy enough for governments to risk letting the booms continue. Once again talk of ‘miracles’ will sound very sick.

Stopford and Strange conclude from their study of the interactions of states and multinationals that there are ‘no more clear guidelines, no simple models, no sure-fire prescriptions for success’ either for governments or for ‘managers as they wrestle with the new demands for innovation in global competition’. [103] But this means that neither the ‘neoliberal’ free market model nor the state directed market model can stop economic policy in ‘developing countries’ (or, for that matter, in developed countries) from going disastrously wrong more often than not. This can be seen by looking not just at the failures of the 1980s, but also at some of the most prominent success stories – Korea, the largest of the Asian NICs, China, the world’s most rapidly growing economy, and India, whose population now accounts for nearly a quarter of humanity.

A few days before the publication in December 1992 of Samuel Brittan’s article extolling the growth of East Asian capitalism, the Far Eastern Economic Review reported: ‘GDP growth in the third quarter was anaemic (by Korean standards), 3.1 percent over the same period in 1991 compared with earlier predictions of at least 5 percent. This is the lowest quarter on quarter growth rate in 11 years.’ [104] A few days later Kim Young Sam won the country’s presidential election. A central part of his campaigning message was that the country was suffering from the ‘Korean’ disease which threatened further economic advance.

The sudden weakness in the Korean economy was not just a reaction to the American and then Japanese recessions, but reflected a deeper problem. The economy had enjoyed very high growth rates through the 1980s. Chun Doo Hwan’s military government had succeeded in coping with Korea’s own debt crisis of the late 1970s and early 1980s by cutting real wages sharply [105] at a time of massive increases in productivity, using the crudest forms of repression to crush the popular resistance which culminated in the Kwangju uprising of 1980.

The large conglomerates, the chaebols, were able to take advantage of the low labour costs of a workforce subject to military repression to carve out markets for themselves, especially in the booming US economy of the Reagan years. At the same time they were able to upgrade Korean industry by imports of plant and machinery from Japan – continuing to copy foreign technology rather than to innovate themselves. [106] Imports from Japan exceeded exports to it by an average of $4.5 billion a year for 1985–9; but these could be paid for from the average excess of exports over imports on US trade of $6 billion. But it was a strategy fraught with potential problems. It depended on the Korean workers putting up with enormous rates of exploitation and the US government ignoring the deficit on its Korean trade. By the late 1980s it had come to grief on both fronts.

A new upsurge of popular unrest which shook the state to its core was followed by a huge wave of strikes which drove up real wages by about 45 percent in three years. At the same time growing US pressure forced the Korean government to begin to open up the economy to foreign goods and finance. The overall result was an acceleration of demand in an already booming economy, leading to a huge surge in construction, property speculation and other services. Manufacturing output grew only 4.4 percent in 1988–9 while construction orders nearly doubled and imports of consumer goods rose 25 percent.

This took place just as the US began to enter into recession and Korean exports of goods such as textiles, steel, machines and chemicals to Japan met increasing competition from other low wage South East Asian countries. [107] By 1991 and 1992 the trade surplus Korea had had throughout the late 1980s had turned into a deficit. Both the state and the major chaebols looked to high technology investments to restore competitiveness. There has been a growth in spending on capital equipment from Japan and elsewhere, ‘reflecting a restructuring in the Korean economy as industry seeks to overcome higher labour costs and competition from cheaper regional producers by upgrading productivity, increasing quality and raising value added.’ [108] But it was one thing to want to turn from low technology to high technology exports. It was another to succeed in doing so. This was shown in two major industries.

The auto industry was supposed to be one of the rising industries. But the much acclaimed entry of Korean made cars, especially Hyundai, into the US market in the mid-1980s had turned sour by the beginning of the 1990s ‘due to the US economic slowdown and the poor reputation for quality that Korean cars gained in the late 1980s’. [109] The magazine Consumer Reports told that Hyundai’s Excel and Sonata 4 were voted among the worst in terms of owner satisfaction in 1989 and 1990. [110] The result was that total auto exports fell from a peak of 576,000 in 1988 to 390,000 in 1990, as against a target of 900,000. [111]

In steel, Posco, the world’s third biggest producer, opened the $2.8 billion Kwangyang integrated steel complex in October 1992, ‘the most modern in the world’. ‘Unfortunately for Posco, though, the world is awash in the basic steel products in which it excels, US and European steel makers are bleeding red ink, while Japanese steel makers have seen their earnings nose dive’. [112] As a result the price it got for its exports fell by 12 percent in 1992 and its profits depended on it exploiting its near monopoly position in the home market to charge 19–20 percent more than prevailing international prices. [113]

Finally, the turn to high technology industry is held back by lack of resources for the necessary investment – the US auto giant General Motors spent more on research and development in 1990 than all of South Korean business combined. [114] Some chaebols are gambling on breaking through in key high technology industries – as with Posco’s attempt to diversify into telecommunications and the manufacture of silicon wafers. The government launched a ‘G7 project’, aimed at pushing Korea towards joining the major industrial powers through building up ten major research areas. But these are gambles, only a few of which are likely to be successful, given the lack of resources to sustain them all. [115]

While waiting to see if any of its gambles work, South Korean industry is having a hard time. ‘Rising stockpiles of goods such as electronics and cars are testimony to the increasing competition the country is facing in the export market ... Recessions in the developed economies have cut demand for South Korean cars, electrical appliances, clothing and other consumer goods. And what goods can be sold are facing diminishing price competitiveness against comparable quality exports from ‘transplant factories’ set up by regional or multinational corporations in China and South East Asian countries ...’ [116] When it comes to the country’s second most important export industry, textiles, ‘A stroll through a clothing market or department store reveals the dismal state of the nation’s garment and textile industry. Prices on clothing have been slashed by more than 50 percent in recent weeks ... the direct result of rising inventories of unsold goods on world markets.’ [117]

Against this background, the government had to step in itself in 1991 and 1992 to dampen down the domestic boom and to try to restore the balance of payments by discouraging imports. But this had the effect of making it even more difficult for industry to get access to the more advanced technology required to upgrade its output. There have been growing splits within the ruling party and between the ruling party, the planning agencies and the chaebols, with enormous rows over how restructuring is to take place. [118] Meanwhile some commentators have begun to suggest Korea’s industries are much less efficient and profitable than was generally thought: ‘industrialists are profligate with capital ... They tend to throw money at capital investment rather than working out the most efficient way to grow.’ [119] Much of the rest of the world is still being told to admire the South Korean model, yet in South Korea itself there is considerable concern the model might not work any more.

What the outcome of the present problems will be no one can foresee. Korea is still a relatively small player on the international capitalist stage, and so may be able to find niches for its exports: it is easier to find niches if you produce only 2.9 percent of world high technology exports as South Korea does, than if you produce 6.3 percent as Britain does or 10.8 percent as Germany does. [120] The point, however, is that the Korean example of an export dependent economy is not one which is generalisable to the whole world, and the more attempts are made to generalise it – for instance by trying to imitate the Korean example in Malaysia, Thailand or South Eastern China – the more Korea itself is going to be pushed into crisis, that is, unless it can shift to a different model of capitalist development. But the first moves in that direction have produced a speculative inflationary boom, leading straight into at least the beginnings of a recession. There is not much hope in that scenario for the capitalist system as a whole.

Increasingly, it is not just the ‘tigers’ who are hailed as the exception to the world picture, but also the world’s two biggest countries, China and India, which between them account for two fifths of the world’s people. Capitalism, it is said, has produced substantial growth in these countries over the last decade, and so has a progressive role to play for the poorest section of humanity. This is Brittan’s contention (although not, of course, expressed in these terms). And it is a view that even seems to be held, for China at least, by John Ross of the Socialist Economic Bulletin, who writes that ‘economic reform in China has produced the greatest economic success in the world’ and recommends it as a model to Eastern Europe and the former USSR. [121]

However, it is a huge step to go from saying that China has experienced growth and its population an improvement in their lives over the last ten to 15 years, to saying that this represents a future for the world system as a whole. The starting point for China was a very low one. Even today the mass of the Chinese people live in villages, tilling about an acre of land for a family of five, without mechanical power, and supplementing their meagre agricultural output with very elementary forms of non-agricultural work (brick making and building, transporting goods with a horse and cart, making elementary food products like noodles, various forms of handicraft production) and, in a minority of cases, with employment in so called collective or co-operative enterprises (often leased out to individuals who then run them as private capitalist concerns). Even after more than doubling in seven years, the net annual income for each member of the farming population in 1985 was only 398 yuan ($108 at the official exchange rate), and that for workers 1,096 yuan ($246). [122]

Output and living standards began to improve 15 years ago, after years of stagnation. The dismantling of the command economy in the countryside and the introduction of the ‘responsibility’ system gave individual peasant households the freedom to produce the particular crops which left them with the greatest incomes (provided they contracted to sell a certain portion to the state at fixed prices) and to use any surplus labour to work on producing goods and services to sell to other peasants (or, if they live close to towns, to the urban population). Each household had an incentive to maximise its output, as it had not before. The result was a ‘virtuous circle’, in which the desire to feed themselves fully and to obtain elementary consumer goods (more tolerable accommodation, furniture, clothing and so on) encouraged peasants to produce more, and, to some extent, to use the increased output of non-food goods to gain money to improve agricultural productivity.

But this process only took off because of something else – a massive, one off transfer of resources from the state to the peasantry. Under the command economy a massive portion of national output (over 30 percent) had gone into investment and was used to build up heavy industry. There had been claimed GDP growth rates of over 8 percent in the late 1960s and early 1970s [123], but by the mid-1970s they gave way to growing signs of crisis. Agricultural production per head was no higher than 20 years before and 100 million of the rural population suffered from food shortages, despite the government importing large amounts of grain. [124] In desperation, the regime cut back the rate of accumulation temporarily and put considerable resources into the rural sector. It raised the prices it paid for foodstuffs by between 25 and 40 percent, while holding down the cost to the peasants of inputs like fertilisers and steel tools – allowing fertiliser use per hectare to rise to more than six times its 1970 level. [125]

In effect, the state was responding to the crisis of primitive accumulation under the command economy by diverting resources from its own hands into agriculture and consumption. It could do so precisely because those resources existed as a result of three decades of Stalinism. As the Indian economist Hanumantha Rao has pointed out, ‘This high growth is due to the existence of tremendous slack, as capital formation was very high and its utilisation very inefficient.’ [126]

This was not the first time that reform, coming after a phase of primitive accumulation had reached an impasse, had released the resources necessary to restore growth rates. This had happened right across Eastern Europe after the great crisis year of 1956, giving Stalinism another decade and more in which it seemed to superficial observers to be able to develop economies. [127] In China the great forward impetus of the agricultural reform began to run out in the mid-1980s. The growth rate of agriculture fell from 8 percent in 1979–84 to about 3 percent in 1985–8. And, as the great once only transfer of resources from the state sector to agriculture came to an end, ‘the share of capital investment in agriculture declined from 9.3 percent to 3.3 percent of the national budget, in absolute terms from $530 million to $380 million’. [128] At the same time, it was reported, ‘In the villages private funds are being diverted away from agriculture into more lucrative endeavours.’ [129] Peasants preferred to spend any savings on building new houses or on their children’s weddings rather than on investment in improving their land. [130]

The decline in agricultural investment could not be justified by any great improvement in agricultural techniques. For reform had not ‘affected the nature of traditional Chinese agriculture’. In 1989 only one rural household in 13 had a ‘animal drawn cart with rubber tyres’, only one in 20 had a ‘small and walking tractor’, and only one in 200 a ‘large or medium tractor’. Forty percent of households regarded themselves as relatively lucky because they owned ‘handcarts with rubber tyres’. [131] ‘No significant technological breakthrough has taken place’, the average one acre farm remained ‘dispersed into 9.7 plots’ [132], there was little sign of any consolidation of dwarf holdings into more efficient units [133], and rural illiteracy was growing rather than declining. [134]

The result, inevitably, was that the ‘virtuous circle’ in the countryside began to disintegrate by the late 1980s, with ‘rural irrigation systems deteriorating, land being depleted, agriculture machinery old and in disrepair, and a serious shortage of expert agricultural personnel ... Necessary agricultural inputs were becoming all but unavailable ... There was a fall in the effectively irrigated area by 3.4 million hectares, leading to a loss of grain totalling 10 million tonnes’. [135] The official China Daily now reports grain output is likely to fall in coming years due to ‘shrinking arable land and deflated enthusiasm among farmers’ [136], and the government, worried about the political impact of workers going hungry, has had to resume importing grain.

Massive industrial growth accompanied the expansion of agriculture in the 1980s, and total output trebled according to the official figures. But again the process was much more contradictory than is often portrayed. In certain coastal areas industry was increasingly oriented to the world economy, for which it was becoming a major supplier of shoes, toys and other low technology consumer goods: the most developed area, Guangdong (adjacent to Hong Kong), with 3 million workers, receives 80 percent of foreign investment in China and accounts for 80 percent of Chinese exports. There were other regions, however, with mainly heavy industry producing means and material of production for the national economy – much as under the old command economy. In still others industry was centred around towns and cities which, because of poor communication links, catered almost exclusively for the local provincial markets. Finally, in almost all provinces many of the village industries – which with 47.6 million workers [137] account for a very high proportion of the country’s total industrial workforce – were situated away from the main urban centres and catered only for markets in close proximity to themselves. [138]

The result is that the impression which visitors to, say, Guangdong get of a country most of its way to catching up with the developed world is very misleading. Enormously uneven development is occurring. In some coastal provinces it is very rapid: thus the value of Guangdong’s output rose by an astonishing 27 percent in 1991 [139] while per capita GNP has reached $701 for the province as a whole, and $2,000 in the Shenzhen special zone next to Hong Kong. But other regions – and even some rural areas within advanced regions – are stagnating, lacking the transport and communication links needed to gain from growth elsewhere.

Hypothetically, if the Chinese economy were able to develop in isolation from the rest of the world for several decades, then the unevenness might begin to be overcome. However low the productivity of labour in the stagnating areas it would, over time, lead to the building of crude roads and storage facilities, to improvements in local rural industries, to the use of very cheap labour to produce cheap low technology goods for the wider market and to the absorption of more advanced technologies from elsewhere. Even the most backward areas would develop at a snail’s pace. But there is not just uneven development in China. There is combined and uneven development. The vast backward regions are influenced by the much smaller advanced areas. The peasants still toiling 12 or 14 hours a day to keep just above the breadline hear about the minority in the coastal cities lucky enough to own all the modem consumer durables, and may even know about the instant fortunes made on the new stock exchanges or the 63-storey Gitic Plaza complex in Guangzhou, with its hotel, offices, apartments, department stores and restaurants ‘rivalling the most luxurious Hong Kong office blocks in lavishness’. [140] They are no longer content to wait for decades in the hope of gradual improvement. Thus early in 1992, as reports told of an influx of a quarter of million people into Guangzhou from elsewhere in the country, Chinese officials spoke of a ‘surplus rural labour force of 150 millions’, while vice-premier Tian Jiyun warned that ‘rural labourers remain idle for half a year. Without work and income, some of them stir up trouble while others flow to other parts of the country’. [141] There were riots in some regions when the state paid peasants with IOUs rather than cash for their grain and of attacks by peasants on tax collectors elsewhere, on one occasion involving 10,000 people. [142]

Yet, while the mass of poor peasants look with envy at the more advanced regions, the managers in those regions increasingly turn their back on the backward areas as they make the world market their focus and they try to shift from labour intensive low technology production to capital intensive high technology. They use every means available to them to procure the resources needed for investment in their industries, effectively stopping them going elsewhere. Their efforts are matched by others within the ruling class – the heads of state owned heavy industry, generals out to upgrade their weaponry, national and provincial party bosses eager to emulate the lifestyle of the richest entrepreneurs. [143] In the process the poorer regions lose out. Far from catching up, they fall further behind, with an ‘increasing concentration of the poor in hard core, resource-poor regional pockets’ where ‘access to basic education and health care’ is ‘outside the reach of poorer families’. [144]

Such pressures explain the difficulties in sustaining the advances in agriculture after the early 1980s. The resources which had been switched to agriculture were now pulled back into industrial investment, as the total accumulation rate rose from 28.3 percent of GDP in 1981 [145] to close to 40 percent at the end of the decade, higher than virtually anywhere else in the world. [146]

In the renewed sacrifice of agriculture to industrial investment the Chinese regime was following the path of other ‘export oriented economies’. In both South Korea and Taiwan a period of putting resources into agriculture has given way to subordinating agriculture to industry and services, leading to rural decline and an increasing dependence on food imports. [147] But agricultural stagnation is a much bigger problem for the Chinese government than for them. Not only does it force the government to spend sums it can ill afford on imports, it also exacerbates social tensions as more than 10 million people a year flood into the cities and unemployment grows massively, since ‘neither the rural non-agricultural sectors nor the urban economy can create enough employment opportunities for absorbing the surplus labour from agriculture’. [148]

The struggle between rival interests within the ruling class for resources does not just doom dreams of development in wide regions of the country. It also drives the whole national economy into repeated crises. Spells of frenetic investment and economic growth cause shortages of energy and industrial inputs, rapid increases in prices and growing deficits on the state budget – and eventually crisis conditions develop which threaten social instability and force the government to take action to bring the surge in growth to a halt. As the World Bank says, ‘As the 1980s progressed China experienced increasingly severe cycles of economic activity ... Investment in transportation, telecommunications, energy and irrigation have lagged behind those in industry ... As a result, serious bottlenecks in these key sectors became apparent in the latter part of the 1980s.’ [149]

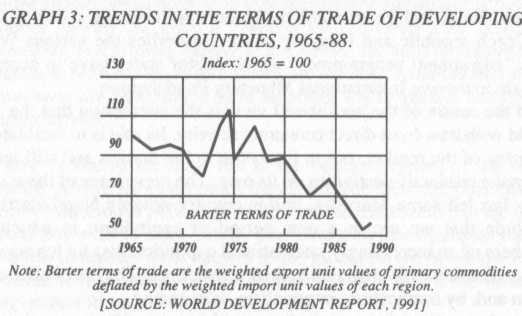

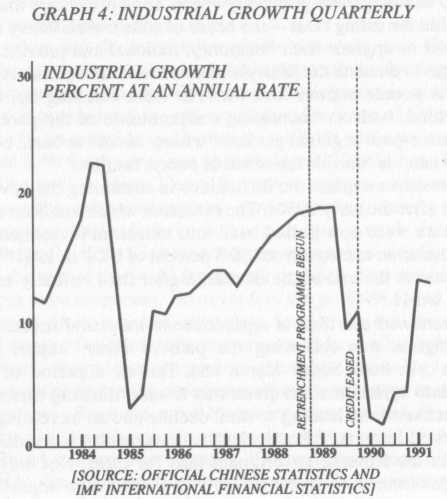

Graph 4 shows the severity of the cyclical fluctuations. Significantly, the last great boom came to a peak just before the massacre at Tiananman Square. Soaring prices threatened the living standards of the mass of workers and peasants, leading to the discontent that found a focus in the student demonstrations. Just as the protests were followed by a severe repression, the boom was followed by a recession – retail sales fell by 7.6 percent in 1989 and industrial growth sank to zero [150], hitting hundreds of thousands of rural and small town enterprises and forcing them to lay off large numbers of workers.

|