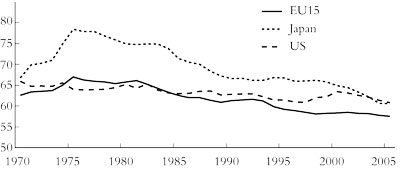

Figure 1: Wage share of national income (percent)

Source: OECD

From International Socialism 2 : 118, Spring 2008.

Copyright © International Socialism.

Downloaded with thanks from the International Socialism Website.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

There is a hierarchy of precedents for financial crises. In August, as things began to unravel, the initial comparisons were with the 1998 collapse of Long Term Capital Management. That is, a freak event in which the sins of a few egg-heads temporarily hit confidence. Then, as it became clear that banks were in pain, the comparator became the 1980s and 1990s Savings and Loan crisis that saw bank losses worth 3 percent of US economic output. Now, after a very nasty week in markets, the whispers are that it might even be the big one: the worst crisis since the 1930s.

– The Lex Column, Financial Times, 7 March 2008

That was the Lex Column of the Financial Times as we went to press. It displays the bewilderment afflicting those who are supposed to be providing some direction to the system as they alternate between sheer panic, fake optimism, and simply hoping things will turn out all right.

The easiest explanation for the crisis is to blame the bankers. The crisis “follows a well-trodden path laid down by centuries of financial folly”, says Ken Rogoff, former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund. [1] Raghuram Rajan, another former IMF chief economist, thinks the problem is the vast bonuses bankers receive when they lend and borrow. [2] Billionaire financier George Soros blames “the financial authorities” for “injecting liquidity ... to stimulate the economy”. This “encouraged ever greater credit expansion”. [3] Even the French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, has joined the chorus, declaring that “something seems out of control” with the financial system. [4] He should know, since his half-brother heads the European wing of the Carlisle Group, whose hedge fund has gone bust.

For supporters of capitalism to heap blame on the financial system is not as strange as it may seem. In so far as mainstream neoclassical economists have explanations for the slump of the 1930s, they are in terms of the operations of the money markets. The same is true of most mainstream Keynesian economists, who now believe their chance has arrived to come in out of the cold after three decades. So the Guardian’s Larry Elliot argues:

This is a chance, perhaps a once in a lifetime chance, to break the dependency culture by forcing big finance to be more transparent, having a clearly defined separation between commercial and investment banking, and by banning some of the more toxic products. [5]

Simply blaming the avarice and short-sightedness of bankers does not explain how they found it so easy to get the funds that they gambled so heavily. It also avoids asking what shape the world economy would have been in without such lending.

In their bewilderment, some strongly pro-capitalist commentators are raising such questions. For instance, Martin Wolf of the Financial Times writes of the crisis originating in “global macroeconomic disorder”, rather than simply “financial fragility” or “mistakes by important central banks”. [6] Commentators such as Wolf have noted a surplus of “savings” over investment in some of the world’s most important economies. The finger is usually pointed at East Asia. The head of the US Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, has cursed this “saving glut in the rest of world” for feeding the upsurge of lending to the US. [7] But surpluses have also been generated nearer to home: “Investment rates have fallen across virtually all industrial country regions”. [8] According to one report:

The real driver of this saving glut has been the corporate sector. Between 2000 and 2004, the switch from corporate dis-saving to net saving across the G6 [France, Germany, the US, Japan, Britain and Italy] economies amounted to over $1 trillion ... The rise in corporate saving has been truly global, spanning the three major regions – North America, Europe, and Japan. [9]

In other words, “Instead of spending their past profits, [US] businesses are now accumulating them as cash”. [10]

Such an excess of saving has an effect noted by John Maynard Keynes in the 1930s – and by Karl Marx 60 years earlier. It creates recessionary pressures. The capitalist economy can only function normally if everything produced is sold. This will only happen if people spend all the income from producing goods – the wages of workers, the profits of the capitalists – on buying those goods. But if the capitalists do not spend all their profits (either on their own consumption or, more importantly, on investment) then a general crisis of overproduction can spread through the system. Firms that cannot sell their goods react by sacking workers and cancelling orders, and this in turn causes further contractions in the market. What begins as an excess of saving over investment ends up as a recession that can turn into a slump.

Keynes and his followers argued that there was a way to stop this happening. The government could intervene to encourage capitalists to spend their savings – by changing tax and interest rates to make it more profitable for firms to invest, by borrowing to undertake investment of its own, or by giving handouts to consumers to encourage them to spend. On occasion such methods have worked in the short term. Government investment or handouts have provided an immediate market for unsold goods, encouraging firms to increase their output and, as a by-product, increasing tax revenues sufficiently to pay for the extra government spending.

But there are inbuilt limits to the long term effectiveness of such methods when faced with a serious recession. Government borrowing must eventually be paid for. Otherwise the value of the currency will decline and inflation will result. If the spending is repaid by taxing profits it reduces the incentive to invest; if it is repaid by taxing consumers, it cuts into their buying power. The measures Keynes himself recommended to British governments in the 1930s would not have been nearly sufficient to end the mass unemployment of the time [11], while attempts to deal with the crisis of the mid-1970s in this way simply added rising inflation to rising unemployment.

In recent years government borrowing and spending have played a role in absorbing the surpluses created by the gap between saving and investment – particularly in the case of the US arms budget. “Official military expenditures for 2001-5 averaged ... 42 percent of gross non-residential private investment”, even though “official figures ... excluded much that should be included in military spending”. [12] But as important as government spending has been the upsurge of borrowing by US consumers to buy things that they cannot afford out of their wages and salaries. Subprime mortgages have been central to this.

In 2001 Alan Greenspan, then head of the US Federal Reserve, encouraged the financial market to let rip and provide for such borrowing when panic over the 9/11 attacks threatened to exacerbate an already deepening recession. [13] The Italian Marxist Riccardo Bellofiore has aptly called this reaction “privatised Keynesianism”. [14] It was not just a question of a central banker doing favours for his friends who ran big private banks. As Martin Wolf recognises, “Surplus savings” created “a need to generate high levels of offsetting demand”, [15] and lending to poor people provided it. “US households must spend more than their incomes. If they fail to do so, the economy will plunge into recession unless something changes elsewhere”. [16] “The Fed could have avoided pursuing what seem like excessively expansionary monetary policies only if it had been willing to accept a prolonged recession, possibly a slump”. [17]

In other words, only the financial bubble stopped recession occurring earlier. The implication is that there is an underlying crisis of the system as a whole, which will not be resolved simply by regulating financiers. Nor, in the medium term, can the sort of action being taken by the US Federal Reserve and the Bush administration solve the problems. They have cut interest rates and taxes to boost consumption. Martin Wolf, using a metaphor from Keynes, has described this as dropping money “from helicopters”. [18] But the most such measures could do would be to reflate the lending and borrowing bubble until it bursts again in a couple of years time. It may well not even achieve that.

Where does the “saving-investment” gap itself come from? Why have firms failed to invest their past profits on the scale they once did?

Studies of the advanced industrial economies show that there was a big drop in average rates of profit from the end of the 1960s through to the early 1980s. [19] There were recurrent bursts of recovery in the mid to late 1980s and 1990s. But by 2000 profit rates had still not risen back to the levels that had sustained capitalism’s longest boom during the quarter century after the Second World War, a time now often called “the golden age of capitalism”. The highest point they reached in the US, around 1997, was only marginally above the level that had seen the onset of the first major post-war recession in 1973–4.

As I have argued in this journal in the past, the partial recovery that did occur was based on three things. The lower rate of profit caused a slowdown in investment, which did not rise as rapidly in relation to new profit as previously. Some firms went bust, particularly during and after the recession of the early 1990s, allowing the remainder to benefit at their expense. Most importantly, there was a general increase in the share of output going to capital as opposed to labour – in Marx’s terms an increase in the rate of exploitation (figure 1). [20]

|

Figure 1: Wage share of national income (percent) |

|

The increased rate of exploitation is not confined to the advanced industrial counties. It is also a feature of the “newly industrialising” countries of East Asia. In China, for instance, real wages have not nearly kept up with rising output, while big sections of the peasantry have probably suffered falling living standards over the last decade. [21] As in the industrial countries, much of the saving in recent years has come from enterprises, [22] although people still have to save an average of about 16 percent of their income if they are going to be able to pay bills for healthcare or to provide for their old age.

The worldwide increase in the rate of exploitation cuts the proportion of total output that workers can afford to buy as consumption goods. The economy is therefore dependent on investment if all the goods produced are to be sold, and the failure of capital to invest creates a potentially recessionary situation that may be hidden by financial and other bubbles.

Such bubbles arise because profits are not invested productively and instead flow, via the financial system, from one speculative venture to another. Each venture seems for a time to offer above average profits – the stock exchange and property booms of the late 1980s, the dotcom boom of the late 1990s, the subprime mortgage boom of 2002–6. Although none of these are directly productive, they can, for a period, provide a boost to spending (through outlay on office buildings, spending by those managing the speculation, the conspicuous consumption needed to attract speculative funds, and so on). That leads to a short term increase in real economic output.

As the economists Boyer and Aglietta have explained, the US boom of the second half of the 1990s rested on “a growth regime whereby overall demand and supply are driven by asset price expectations, which create the possibility of a self-fulfilling virtuous circle. In the global economy, high expectations of profits trigger an increase in asset prices which foster a boost in consumer demand, which in turn validates the profit expectations ... One is left with the impression that the wealth-induced growth regime rests upon the expectation of an endless asset price appreciation”. [23]

This is what is happening today. The most logical explanation seems to be the continuing low long term profitability. The Marxist economist Robert Brenner has used official US statistics to produce figures that show manufacturing profit rates in 2000–5 at levels lower than in either the early 1970s or the 1990s (although higher than in the late 1970s and 1980s). His calculations for all non-financial corporations show them as about a third lower in 2000-6 than in the 1950s and 1960s, and about 18 percent lower than in the early 1970s. [24]

Some commentators hold a different view on trends in long term profit rates. They believe that profit rates have been completely restored by increasing exploitation. This is held to be particularly true in the US, where increased productivity over the past seven years has been accompanied by stagnating wages and the loss of one in six manufacturing jobs. Martin Wolf asserts that “on average, US companies are in decent shape”. [25] The OECD World Outlook asserts that “the non-financial corporate sector is healthy”. [26] The French Marxist Michel Husson was already accepting eight years ago that there were “high levels of profitability”. [27] Today he writes of “a spectacular re-establishment of the average rate of profit since the mid-1980s”. [28] Another leading Marxist economist Fred Moseley wrote recently, “The rate of profit appears to be more or less fully restored” without “a deep depression characterised by widespread bankruptcies that would result in a significant devaluation of capital”, which is what Marx thought “would usually be required”. [29]

There are, however, reasons to believe that Brenner’s account of profitability is the correct one. In recent years companies have tended to exaggerate their profits in order to boost their standing on stock exchanges, to deter takeover bids and to increase the value of “stock options” given to their top managers. So in the last boom in the US, that of the late 1990s, declared profits were up to 50 percent higher than actual profits. [30] There are signs that the same thing has been happening over the past four or five years, with corporations concealing their level of indebtedness, while including in their declared profits proceeds from the financial bubble that have turned out to be fictional.

The mainstream economist Andrew Smithers has drawn attention to the way the profitability figures provided by companies give an exaggerated picture of what is really happening. He points out that the US’s official figures shown in the “Flow of Funds” accounts involve adjustments that have the effect of “massively boosting US net worth by the addition of ‘statistical discontinuities’ and rising property values”. [31] In fact, the Flow of Funds accounts showed increases in “real estate worth” alone accounting for $757 billion out of the $1,239 billion increase in “net worth” of the whole of the non-farm, non-financial corporate sector in 2005 (while “discontinuities” accounted for another $506 billion). [32] According to Samuel DiPiazza, chief executive of PwC, one of the US’s four big accounting firms, many industrial concerns in the US have looked to finance to augment their profits in recent years and have “invested in the asset-backed and mortgage-backed securities”. [33]

In other words, much of the apparent profitability of US corporations has depended upon the way the bubble increased the paper value of their financial and real estate assets well above their underlying real value.

Fred Moseley notes the way in which corporations have been hiding their level of debt by “the increasing transfer of debt from the books of non-financial corporate businesses to ‘special purpose vehicles’”. [34] But hidden debt of this sort suggests that profitability on investments made in the past has not been as high as claimed, and that Brenner’s account of relatively low profit rates would seem to be correct.

Finally, even if average profitability had risen as much as is sometimes claimed, it would not necessarily have been enough to raise the level of investment. Martin Wolf added a rider to his assertion that on average companies were in “good shape”, to the effect that there is a “fat tail” of companies with low profitability and heavy debt. [35] In other words, even if some companies have profits high enough to undertake large scale productive investment, there are many others that do not (among them are such giants as General Motors and Ford). This would leave investment in the economy at a low level, leading to a repeated tendency to recession.

The present financial crisis is a symptom of the same underlying problem that has plagued world capitalism since the mid-1970s. Increased exploitation has been able to stop a further downward plunge in the rate of profit, and even to restore it somewhat. But it has not been able to bring it back to a level that will persuade capital to invest sufficiently to avoid recurrent recessions. And the omens this time round look serious.

This is recognised even by many of those who see it as caused by runaway finance. They see that only the most drastic remedies can put a check on it, but that such remedies could precipitate a deep recession. Soros, for instance, argues that “credit expansion must now be followed by a period of contraction because some of the new credit instruments and practices are unsound and unsustainable”, [36] but then worries that the outcome might be not just a US recession but a world slump.

The spread of recession increases the problems of the financial sector and spreads them to part of the productive sector. It makes it impossible for all sorts of very big borrowers to recover enough of what they have lent to repay what they owe. Nouriel Roubini of New York University’s Stern School of Business sees “a rising probability of a ‘catastrophic’ financial and economic outcome” with “a vicious circle where a deep recession makes the financial losses more severe and where, in turn, large and growing financial losses and a financial meltdown make the recession even more severe”. [37]

Such fears explain the behaviour of the US Federal Reserve and the Bush government. They are afraid of the crisis deepening, and so are pouring money into the system with a series of interest rate reductions and with the first tax cuts that have benefited anyone apart from the very rich. It is an approach that has led the Wall Street Journal to accuse Bernanke of being a “Keynesian”. [38]

Such a policy really amounts to trying to overcome the collapse of one bubble by inflating another one. But that is likely to add to inflationary pressures at a time when food prices worldwide are soaring and oil prices are at a record level. It also risks provoking a loss of faith in the value of the dollar when it is already falling in value against currencies such as the euro. The fact that the US authorities are prepared to take such a risk, with the potential damage to US global hegemony it entails, is a sign of how seriously they take the situation.

Yet the approach shows signs of failing. It faces all the problems that have beset mainstream Keynesian attempts to deal with crises in the past. The tax cuts are not on anything like the same scale as the private loans that people are now under enormous pressure to repay, while the cuts in interest rates are not feeding through. As Wolfgang Müncher argues:

The US Federal Reserve has cut short term rates by a cumulative 225 base point, yet borrowing costs for US consumers and companies have gone up. While the European Central Bank has stoically kept short term interest rates at 4 percent, rates charged to consumers and companies have increased. [39]

To have more than a short term effect, the US government would have to be putting enough money into people’s pockets not only to absorb the worldwide surplus of saving over investment, but also to reassure them that they do not need to save it in order to protect themselves against the impact of a slump. Giving banks or people the incentive to use their money is not the same as making sure they do so. That is why mainstream economists are quoting Keynes’s adage that you “can’t push on a string”.

It is also why some mainstream commentators are convinced that the US government will be forced to go much further. So George Magnus, chief economic adviser to the UBS financial services company, argues that the cost of nationalising Northern Rock is “pretty small beer compared with the kind of activities which I think are going to take place in the United States ... a bailout for homeowners in the United States is as close to a surefire thing as I can imagine. The losses on mortgages are so high and the stories and estimates which ... people make about repossessions and delinquencies in the housing market are so high that, especially in a presidential election year, I think it’s just inevitable that there will be very strong action”. [40]

But then Magnus holds that this crisis is much more serious than the collapse of the Long Term Capital Management hedge fund in 1998, the Stock Exchange Crash of 1987 or the Mexican crisis of 1995. “This is different: (a) because it’s big; (b) because it’s widespread; and© because it is about solvencies, not just about liquidity. And solvency requires a totally different policy approach than just a liquidity problem.” Crises of liquidity occur when firms are profitable but lack the cash to pay their immediate bills; crises of solvency occur when they are operating at a loss.

Müncher sees this as a “hugely contagious solvency crisis” and suspects that “we will ultimately end up with some combination of regulatory relief, fiscal bailouts, nationalisations and many, many bankruptcies of financial institutions that are not too big to fail”. [41]

Two nightmares haunt defenders of the system. One is the great slump of 1929-33. This is not completely off key. There are similarities between what happened in the 1920s and what has happened in recent years. In both cases profit rates were stopped from falling from previously fairly low levels by increased exploitation, creating underlying imbalances between production and consumption that were bridged, for a period, by speculation, unproductive use of resources, and lending to finance consumption. [42] Then, as now, it only required the bubble to deflate for the underlying imbalance to make itself felt.

There is, however, one important difference. The level of government spending, especially military spending, in the US is much higher today. As noted earlier, this has played a role alongside private borrowing in maintaining demand in recent years. Short of the US state going bankrupt this government spending provides a floor below which the American economy will not sink. Weaker capitalisms may not, however, be so fortunate.

The second, slightly less frightening, scenario is what happened to Japan in the early 1990s. The collapse of a boom based on a real estate bubble resulted in a long period of near stagnation that has not yet come to an end 16 years later. The losses incurred by the Japanese banks were around the same level as those incurred so far in the US (losses that could well double in the months ahead). Nevertheless, most mainstream commentators are keen to stress that the US today is different – in particular that the Federal Reserve is not making the supposed “mistakes” made by Japan’s central bankers. But that rests on the assumption that the root of both crises lay purely in finance, and not in tendencies in the productive sector of the economy as well. In fact problems of profitability in the productive sector played a big role in Japan [43] and, as we have seen, they are central to what is happening now.

Japanese capitalism has, of course, survived, despite growing so slowly. But a similar prolonged period of stagnation like that would have a traumatic effect on the US, deepening the so far unfocused bitterness to be found within its working class and shaking US global hegemony still further. It is not really so surprising that, faced with such a possibility, those who run the US state are ignoring the neoliberal credo they preach to the rest of the world.

Economic crises in the modern world always have a political impact. This is because the biggest capitalist concerns still operate from national bases, despite all the hype about globalisation. Each relies on its own national state to defend its interests around the world against those of rival multinationals based in other national states. This is especially true at times of crisis.

Because crisis affects the various sections of global capitalism in different ways, governments and central banks react with policies that move in different directions. So over the past eight months the US Federal Reserve has been pouring money into the economy and making big cuts in interest rates; the British government, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank have been trying to restrain public expenditure and keep interest rates high; the Chinese state has been trying to slow down its economy for fear of inflation (and popular unrest) getting out of hand.

If the crisis gets more severe, the disagreements could get quite nasty, with each state trying to exert pressure on others to get its way. In the past the US state could usually use its influence on the European and Japanese governments to get them to accept some of the pain involved in solving its problems. The most famous case was the “Plaza Agreement” 23 years ago, in which the Europeans and Japanese agreed to take action together to reduce the international value of the US currency. One reason the US could get its way was that the other states were dependent on US financial and military power.

The US will try to exert similar pressures now, but it will do so from a weaker position. The most rapidly growing national economy is no longer that of Japan, but that of China – and China is nothing like as dependent on the US economically, financially or militarily as Japan was (and still is). [44] The US government can be expected to try to counter its current economic weaknesses through the use of the other tools at its disposal. This means the US showing it has the military power to determine what happens in wide areas of the world and upping the ideological barrage against those other major powers that might stand in its way. Expect more crocodile tears about the horrors in Darfur from those who have created horrors on an even greater scale in Iraq, Afghanistan, Congo-Zaire and Somalia. And expect them to create more such horrors.

It is not only internationally that financial crisis is finding political expression. Different capitals within particular countries are differentially affected by the crisis – it has hit Lloyds and Barclays to a different degree to Northern Rock – and they are attracted to different ways of trying to resolve it. Those who look to serve the interests of capital pull in different directions, develop different perspectives and denounce each other when things go wrong. In the process capitalist hegemony itself can be damaged, particularly in the weaker capitalist states worst hit by the crisis.

We can expect further political ructions in Britain, precisely because the economy has become more dependent on finance as a source of profits (and a centre of employment) over the past two decades than any other advanced industrial state. [45] Wolfgang Müncher even holds that “the UK economy is about to undergo a downturn at least as large as that of the US – maybe even worse, because of an even more inflated housing market and because the financial sector constitutes a larger share of gross domestic product”. [46]

Mervyn King, the governor of the Bank of England, has reacted to these problems by calling for “a genuine reduction in our standard of living compared to where it would otherwise have been”. [47] New Labour, of course, is intent on trying to achieve that through continuing its cuts in real public sector wages for at least another two years, even as food and energy prices soar and those who took advantage of cut rate mortgage deals in recent years face a massive escalation of housing costs.

The inevitable bitterness can have a big ideological fallout. Any recession exposes the claims that are always made during booms, however short lived, about the wonders of capitalism. Martin Wolf, a staunch defender of the system, fears that “the combination of the fragility of the financial system with the huge rewards it generates for insiders will destroy something even more important – the political legitimacy of the market economy itself – across the globe”. [48]

Such worries over “legitimacy” explain the New Labour government’s attempts to avoid nationalising Northern Rock, even after it became clear that this was the only way to stop a collapse that would further damage the rest of the financial system. Nationalisation as such is not necessarily inimical to capitalism. It was a characteristic feature even of some of the most right wing regimes in the period from the early 1930s to the mid-1970s. Nor is it some peculiar aberration in the present period. Governments, including those often called “neoliberal”, have repeatedly taken over the running of parts of endangered national banking systems to capitalist applause in the past two decades (Chile in the early 1980s, the US in the late 1980s, Japan in the 1990s).

However, such actions stand in clear contradiction to the way neoliberal ideology is used to try to legitimise the current phase of capitalism. That ideology portrays the market as a mechanism of superb efficacy that must not under any circumstances be interfered with. Every time nationalisation is carried through, even the most thorough capitalist form of nationalisation, it challenges that view. It shows that conscious human action can override the supposedly natural laws of the market – and raises the questing of why that action cannot be in the interests of the mass of people rather than in the interests of capital.

Many more such questions are going to be raised as the effects of the monetary crisis work their way through the system. And they will do so as the different national governments try to pass the burden on to those who labour for capital. No wonder it is not only the bankers who are worried as well as bewildered.

1. Quoted in the Independent, 19 January 2008.

2. Quoted By Martin Wolf, Financial Times, 15 January 2008.

3. Financial Times, 22 January 2008.

4. Quoted on the Financial Times website, 29 January 2007.

5. Guardian, 24 January 2008.

6. Financial Times, 22 January 2008.

7. Quoted in Godley, Papadimitriou, Hannsgen and Zezza, 2007.

8. Terrones and Cardarelli, 2005, p. 92.

9. Corporates are Driving the Global Saving Glut, JP Morgan Securities, 24 June 2005.

10. Papadimitriou, Shaikh, Dos Santos and Zezza, 2005.

11. Harman, 1996.

12. Magdoff, 2006, p. 5. Net physical investment by non-farm, non-financial corporate business in the US in 2006 amounted to $299 billion, the US military budget $440 billion.

13. For a longer account of the emergence of the subprime crisis, see Lapavitsas, 2008.

14. Speech at the Historical Materialism conference, London, November 2007.

15. Financial Times, 22 January 2008.

16. Martin Wolf, Financial Times, 21 August 2007.

17. Martin Wolf , Financial Times, 22 January 2008.

18. Martin Wolf, Financial Times, 12 December 2008.

19. For detailed analysis, see Harman, 2007a.

20. The usual measures of the shares of capital and labour, as in the graph shown here, give only a rough indication of the trend in the rate of exploitation, since, for Marx, surplus value extracted from productive labour also pays for a mass of “unproductive” activities that serve to bolster capitalism (such as the forces of “law and order”, the military and the financial system). For simplicity I use the conventional measures here.

21. For more on this, see Charlie Hore’s article in this issue.

22. Terrones and Cardarelli, 2005, Box 2.1, p. 96.

23. Aglietta, 2000, p. 156. The discussion between Aglietta and Boyer was indicative of a situation where their Regulation School’s effort to explain the long term trajectory of capitalism was coming adrift. For a comment on this, see Grahl and Teague, 2000, pp. 169–170. For an early critique of the Regulation School, see Harman, 1984, pp. 141–147.

24. Handout provided to participants in the Historical Materialism conference, London, November 2007.

25. Financial Times. 19 February 2008.

26. Quoted by Andrew Smithers, response to America’s Economy Risks Mother Of All Meltdowns, economists’ forum, Financial Times website, 20 February 2008.

27. Husson, 1999.

28. Husson, 2008.

29. Is the US Economy Headed for a Hard Landing?, www.mtholyoke.edu/~fmoseley/hardlanding.doc.

30. The Economist, 23 June 2001, quoted in Harman, 2001. For the same phenomenon in the late 1980s, see Harman, 1993.

31. Andrew Smithers, response to America’s Economy Risks Mother Of All Meltdowns, economists’ forum, Financial Times website, 20 February 2008.

32. Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States, Flows and Oustandings, second quarter 2007, Federal Reserve statistical release, p. 106, table R102, www.federalreserve.gov/RELEASES/z1/20070917/. The “disconunities” figure jumped by $323 billion between 2005 and 2006-equivalent to nearly a fifth of the increase in net worth for the whole sector.

33. Quoted in Financial Times, 6 February 2008.

34. Is the US Economy Headed for a Hard Landing?, www.mtholyoke.edu/courses/fmoseley/HARDLANDING.doc.

35. Financial Times, 19 February 2008.

36. Financial Times, 22 January 2008.

37. Quoted by Martin Wolf, Financial Times, 19 February 2008.

38. Wall Street Journal, 18 January, 2008.

39. Financial Times, 10 March 2008.

40. Interview on the Financial Times website, 25 February 2008.

41. Financial Times, 10 March 2008.

42. For accounts of the origins of the crisis of 1929-33, see Corey, 1934, and Harman, 1984, chapter two.

43. For criticism of views that ignored the fact that the crisis developed in the non-financial sector, see Kincaid, 2001.

44. This point was made by Peter Gowan at a public lecture at the London School of Economics in February 2008 – and repeated in a comment on the Financial Times online economists forum on 21 February by Robert Wade, who chaired the lecture.

45. See Harman, 2007b.

46. Financial Times, 24 February 2008.

47. Press conference on the Bank of England’s February inflation report, quoted in Financial Times, 28 February 2008.

48. Financial Times, 15 January 2008.

Aglietta, Michel, 2000, A Comment and some Tricky Questions, Economy and Society, volume 29, number 1.

Corey, Lewis (a.k.a. Louis Fraina), 1934, The Decline of American Capitalism, www.marxists.org/archive/corey/1934/decline/.

Godley, Wynne, Dimitri Papadimitriou, Greg Hannsgen and Gennaro Zezza, 2007, The US Economy: Is there a Way Out of the Woods?, Strategic Analysis, November 2007, The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College.

Grahl, John, and Paul Teague, 2000, The Regulation School, Economy and Society, volume 29, number 1.

Harman, Chris, 1984, Explaining the Crisis (Bookmarks).

Harman, Chris, 1993, Where is Capitalism Going?, International Socialism 58 (Spring 1993).

Harman, Chris, 1996, The Crisis of Bourgeois Economics, International Socialism 71 (Summer 1996), http://pubs.socialistreviewindex.org.uk/isj71/harman.htm.

Harman, Chris, 2001, The New World Recession, International Socialism 93 (winter 2001), http://pubs.socialistreviewindex.org.uk/isj93/harman.htm.

Harman, Chris, 2007a, The Rate of Profit and the World Today, International Socialism 115 (Summer 2007), www.isj.org.uk/index.php4?id=340.

Harman, Chris, 2007b, New Labour’s Economic ‘Record’, International Socialism 115 (Summer 2007), www.isj.org.uk/index.php4?id=335.

Husson, Michel, 1999, Surfing the Long Wave, Historical Materialism 5 (winter 1999), http://hussonet.free.fr/surfing.pdf.

Husson, Michel, 2008, La Hausse Tendancielle du Taux d’Exploitation, Imprecor, http://hussonet.free.fr/parvainp.pdf.

Kincaid, Jim, 2001, Marxist Political Economy and the Crises in Japan and East Asia, Historical Materialism 8.

Lapavitsas, Costas, 2008, Interview: The Credit Crunch, International Socialism 117 (winter 2008), www.isj.org.uk/index.php4?id=395.

Magdoff, Fred, 2006, The Explosion of Debt and Speculation, Monthly Review, November 2006, www.monthlyreview.org/1106fmagdoff.htm.

Papadimitriou, Dimitri, Anwar Shaikh, Claudio Dos Santos and Gennaro Zezza, 2005, How Fragile is the US Economy?, Strategic Analysis, February 2005, The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College.

Terrones, Marco, and Roberto Cardarelli, 2005, Global Balances, a Savings and Investment Account, World Economic Outlook, International Monetary Fund.

Last updated on 12 December 2019