|

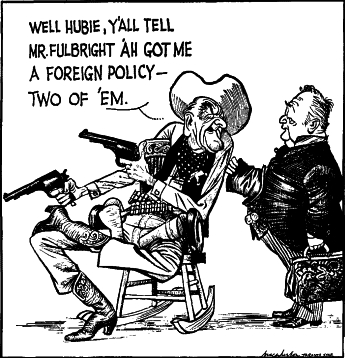

Macpherson, Toronto Star, April 23, 1966

Source: International Socialist Review, Vol.27 No.4, Fall 1966, pp.137-144. [1*]

Transcription/Editing/HTML Markup: 2006 by Einde O’Callaghan.

Public Domain: George Novack Internet Archive 2006; This work is completely free. In any reproduction, we ask that you cite this Internet address and the publishing information above.

The front page of the Sunday June 26 New York Times carried a report from its diplomatic correspondent in Washington with the following headline: “Titanic Struggle Seen in Red China.” This is stated as the opinion of experienced observers in the nation’s capital who have much better sources of information on China’s internal affairs than the friends of revolutionary China.

This view is altogether different from that presented by official spokesmen of Mao’s regime. One editor says that “an excellent situation without parallel” prevails in China and warns the watching world not to be misled by superficial appearances. This was echoed by Foreign Minister Chen Yi who asserted in Peking June 27 that Communist China’s enemies would gain nothing from the purge now in progress.

What is the real state of affairs? If we simply take what the Chinese press itself has been saying, and the individuals who have already been disgraced and deposed, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the Chinese Communist Party and its rule are passing through an even more severe political crisis than the liquidation of the Kao Kang group in 1954-1955 and the short-lived “hundred flowers bloom” disturbance in 1957.

Here is how official sources depict the situation. Starting last October and gaining momentum and scope month by month, a massive campaign has been mounted from one end of the country to another against erring intellectuals. According to a Hsinhua dispatch from Peking June 11, “the magnitude, intensity and strength of this great proletarian cultural revolution are without precedent in history. The whole of China is a vast scene of seething revolution.”

“Hundreds of millions of workers, peasants and soldiers ... armed with Mao Tse-tung’s thought,” writes the newspaper Red Flag, have been engaged in unmasking the hidden agents of the class enemy. “They have been writing articles, holding discussions, and putting up posters written in big characters to sweep away the ogres of all kinds entrenched in ideological and cultural positions ... Those who echo the imperialists and the reactionary bourgeois ‘specialists,’ ‘scholars’ and ‘authorities’ have been routed, one group after another, with every bit of their prestige swept into the dust. The reactionary strongholds controlled by members of the sinister anti-party and anti-socialist gangs have been breached one after another.”

Their conspiracy extended into every sector of the ideological and cultural front. The “bourgeois representatives wrapped in red flags” had built bases in the fields of philosophy, economics, history, literature and the arts, the drama, movie-making, education, dancing, opera, journalism and publishing.

“The most reactionary and fanatical element in this adverse current,” writes Red Flag, “was the anti-party ‘three family village’ gang.” This gang consisted of the noted historian Professor Wu Han, deputy mayor of Peking, Teng To, secretary of the Peking Municipal party committee and former chief editor of Jenmin Jih Pao, the foremost Communist newspaper, and Liao Mo-sha, former departmental director of the Peking party committee.

These prominent Communists are really “bourgeois rightists” at heart. Such types have been carrying on their nefarious activities in secret for at least the past ten years; some accounts say since 1949. These began, according to Hsinhua and Red Flag, back in 1957 during the “let a hundred schools of thought contend” days. Temporarily subdued, they renewed their offensive between 1959 and 1962, emboldened by the “temporary difficulties resulting from sabotage by the Khrushchev revisionists and serious natural calamities in China.” Interestingly, to preserve Mao’s reputation for infallibility, no mention is made of any wrong or reckless decisions made under his leadership in connection with the mishaps of the Great Leap Forward, like the fiasco of making steel in backyard furnaces.

Prof. Wu Han headed the pack of revisionist rascals. He wrote a series of articles and plays between 1959 and 1962 satirizing and criticizing the regime in veiled symbolic terms. He thus “served US imperialism as a cultural servant, posing as a revolutionary cadre while engaged in counterrevolutionary dealings.”

Other papers point to Teng To as the leader of “the anti-party, anti-socialist gang of conspirators.” Teng wrote in one of his parables: “It is only a wild dream of foolish men to know everything and possess inexhaustible wisdom.” Since only one man in Communist China has such omniscience, this is construed as questioning Mao’s infallibility. Teng is thus judged guilty of the well-known crime of lese majeste.

A widening range of intellectuals, educators, writers, scholars, journalists in most of the principal cities and educational and cultural institutions, including the author of the regime’s national anthem, have been implicated in the ever-expanding dragnet of the purge.

The most eminent is Kuo Mo-jo. The 78-year-old Kuo is the country’s most prominent scholar, who has been hailed as the “Victor Hugo” of China by L’Humanité, the official daily of the French Communist Party. He is president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, chairman of the All-China Federation of Literary and Art Workers and of the China Peace Committee, and holds more than 20 other official positions.

This old man was forced to comply with the pattern of the campaign by making a “self-criticism” last April to the Standing Committee of the National Peoples Congress of which he is a vice chairman. There he confessed that all his voluminous writings deserved to be burned because he had not deigned to learn from the workers and peasants and had neglected to apply Mao’s teachings correctly.

Mao’s regime has not publicly hurled heretical banned books into the bonfire. But to demand that all writings conform to Mao’s thought, as evidenced by this obsequious obeisance to Mao’s omniscience by China’s foremost scholar, demonstrates how stringent is the thought control being enforced by the so-called “cultural revolution.”

More significant than the humiliating confession of Kuo Mo-jo is the fact that none of the writers denounced as counterrevolutionary has yet followed his example. For example, Teng To has not recanted his heresies. Last December he held a meeting of students to urge the creation of a hundred flowers atmosphere in which everyone could write “according to our own views”. This is, of course, now less permissible and possible than ever.

The highest personage thus far involved in the purge is Peking’s Mayor, Peng Chen, member of the Politbureau and one of the top ten in the Communist Party hierarchy. Removed with him was a large group of notables located in the capital. Among them were Lu Ping, president of Peking University, and two other leading officials; the entire editorial boards of the Peking Daily, the Peking Evening News, and the fortnightly magazine Front Line; a deputy director of the propaganda department of the Central Committee, Chou Yang, who is well-known as an exponent of the official line in the polemics with Moscow and in philosophy. Chou has served as vice-minister of cultural affairs and vice-chairman of the All-China Federation of Literary and Art Circles since 1951. Lu Ting-yi, director of the propaganda department of the Central Committee and minister of Culture, has not been seen in Peking since the end of February.

The purge has struck hardest in Peking, the political, intellectual, educational capital of the country. It has been focused on the campus and youth movement there. The purge victims have been accused of using Peking University as a base for attempting to win over the younger generation. They have been charged with seeking to “lead students astray onto the road of revisionism and train them as successors for the bourgeosie.”

The resistance of the older intellectuals and their refusal to recant is connected with the militant temper of the students and their opposition to the regime. Before the president of Peking University was removed, the papers reported struggles between those students who backed the oppositionists and those mobilized by party officials and the government. Reporters were ordered to apply for official permission to visit the university.

What are these student rebels like, what is their mood? Let me cite on this point some testimony in a letter received in June from a veteran Japanese Marxist:

“Last summer,” he wrote, “one of my sons, a freshman at a Tokyo university, helped organize a tour in which 130 university students went to China. They visited Canton, Shanghai, Peking and other places. They were welcomed by the young people and university students there with such enthusiasm that they were completely overwhelmed. These encounters were spontaneous and passionate, even though they were organized under official auspices.

“In brief meetings the young people became so friendly that many, almost all, on both sides embraced each other and parted with tears, though few could speak each other’s language. Upon their return the Japanese student delegation compiled a booklet of their impressions which, however naive, can by that fact be more trusted in certain respects than those of better-known, more sophisticated people.

“I learned through them that the Chinese students at the leading universities, together with other young men and women, are still in a more or less revolutionary frame of mind. They yearn for something great and true with a common aspiration. They number by the millions, by the tens of millions, in the cities.

“In your Militant article you quoted Victor Zorza’s words comparing the present situation in Peking with the crisis in the Soviet leadership a few months before the death of Stalin. That may be true so far as the gravity of the conflict in the leadership is concerned.

“But in regard to these tens of millions of young people it rather resembles to some extent the situation in 1927 before Stalin’s suppression of the Left Opposition. These intellectuals and young people are not indifferent. They are strikingly bright, burning with intense curiosity and revolutionary zeal.

“Their fiery, non-individualistic rebel spirit makes them different from students in capitalist countries and perhaps also from Soviet Russia. They still live in a pre-Stalin era. They study Lenin’s works as well as Mao’s, although all the documents of the Comintern are not at their disposal.

“The writings of the figures now accused of counterrevolution are sharply critical of the present leaders. None of the accused, except for the old Kuo Mo-jo, has yet recanted. If the grown-ups can become so critical, then the dissidence of these young people with bright intelligence must be unbearably acute.

“Behind this surprising militancy of the adults is the resistance of these young men and women. We should not forget the existence of many victims of the ‘Great Leap Forward’ and other affairs. Each of these has involved thousands of young men.

“We know of one prison alone in the suburbs of Peking where hundreds of youthful political prisoners have been doing heavy labor for many years, resolutely refusing release on the condition of recanting. They are not Trotskyists, at least they do not call themselves such. (Many Trotskyists who were arrested in 1949 and later, also remain in prison.) Many Chinese youth and students know of their existence and resistance.”

This testimony is confirmed by two recent events. The purge has been extended to the Communist Youth League of Peking whose leading officials were ousted on June 15. The news of their dismissal was reported to have had an “electrifying impact” on the capital. Meanwhile, 6,000 students and intellectuals were ordered back from farms and factories to reinforce the ranks of the party on Peking University’s campus. By official decree, no new students will be admitted to the first year of the universities for about six months while the curriculum is being reformed.

What is the regime afraid of? Its spokesmen say that the purge victims were engaged in a counterrevolutionary conspiracy aimed against socialism and directed toward the restoration of capitalism in connivance with Chiang Kai-shek, the native capitalists and landlords, and US imperialism.

These “unsteady elements in the revolutionary ranks” were plotting to take power. They had two prototypes in view, it is said. One was the “blatant counterrevolutionary molding of public opinion by the Khrushchev revisionist group which, soon after, staged a ‘palace’ coup and usurped party, military and government power, subverting the dictatorship of the proletariat.”

The other was the 1956 Hungarian revolution where “the counterrevolutionaries also prepared public opinion before they took to the streets to create disturbances and stage riots. This counterrevolutionary incident was engineered by imperialism and started by a group of anti-Communist intellectuals of the Petöfi Club. Imre Nagy, who at that time still wore the badge of a Communist, was ‘fitted out with a king’s robe’ and became the chieftain of the counterrevolution.”

This parallel between the views of the critics and the Hungarian Communist intellectuals has a tell-tale character. The Petöfi Circle was a debating club formed in Budapest in March 1956 by the Communist youth organization as a response to the liberalization after the Twentieth Congress of the Soviet CP. Students, writers, philosophers, economists, scientists, workers and dissident party members used it as a platform for vehement criticism of the crimes, blunders and deficiencies of Rakosi’s Stalinist regime. The controversies and revelations in this unofficial parliament played a key role in the ideological preparation for the popular outburst in October that was smashed with the aid of Khrushchev’s tanks and the approval of Mao Tse-tung.

In crushing the Hungarian uprising, Khrushchev charged that it was “counterrevolutionary,” and he associated it with the bourgeois restorationist currents that also existed in Hungary. Mao agreed. Chou En-lai even toured Eastern Europe to bolster Khrushchev’s hand in this counterrevolutionary repression of the socialist aspirations of the Hungarian intellectuals, students and workers. The Hungarian workers, however, clearly demonstrated that what they wanted was proletarian democracy and not a return to capitalism.

The repeated reference to the Petöfi Circle are all the more interesting, since they may indicate the existence of similar left wing ferment in China. This is suggested by references linking Peng Chen with Liu Hsi-ling, the Peking university woman student who was the outstanding spokesman for the revolutionary youth critics of the regime in 1957. By deliberately mixing up a tendency of this kind with the remnants of the “progressive bourgeoisie,” whose parties are still represented in the government of the People’s Republic of China, Mao would be folio wing the pattern set by Khrushchev, who, of course, was only applying what he learned from Stalin.

The citation of these political precedents also indicates why the Mao directorate is so adamant against any liberalization of the atmosphere and any relaxation of the strict regimentation of thought. It fears that criticisms voiced by students and intellectuals may, as in Hungary, set off explosions among the masses or, as in the Soviet bloc, stimulate strong demands for debureaucratization.

Any outspoken dissidence tends to unsettle the “cult of the individual” enshrined in the mystique of Mao (who has not published anything of significance since 1957) as the all-wise, infallible, unquestionable leader. The unrestrained adulation of Mao which presently permeates Chinese life surpasses the homage once paid to Stalin. This sickening relapse into backwardness, which is totally incompatible with the scientific spirit of Marxism and the democratic principles of socialism, has become a charter for the uncontrolled rule of the Chinese Communist bureaucracy. They have made the worship of Mao’s omniscience mandatory upon all in order to keep a firm grip on the reins of power and beat down all criticism of their actions.

What has called forth such a tension within the leadership and such a breach between Mao’s entourage and young and old intellectuals? Four factors appear to have converged from different sources at the same time: the uninterrupted sequence of setbacks which have weakened and worsened China’s international position; economic difficulties at home; the growing threat of US military attack; and the possible prospect of Mao’s death which raises the problem of his succession.

Let us first discuss the international developments.

The high-water mark of China’s influence in the Communist world, after the outbreak of the Sino-Soviet dispute at the beginning of the 1960’s, was the Moscow meeting of 19 Communist parties in March 1965. Although Peking and its closest allies boycotted this meeting, the refusal of the participants to concede any of the Kremlin’s key demands there was a great gain for Peking.

Soon after that, a sharp turn took place. The new stage began with the demonstrations of Chinese and Vietnamese students before the US embassy in Moscow which was broken up by Soviet police and soldiers. This incident was staged by the Chinese embassy on orders from Peking in protest against the Kremlin’s behind-the-scenes negotiations on Vietnam with Washington. This action, however justified by the sluggish Russian reaction to Johnson’s bombings of north Vietnam, was widely construed as a provocation and a deliberate widening of the breach between the two powers when greater solidarity was in order.

This feeling was confirmed when the Chinese followed up with vehement accusations that Moscow’s guiding line was “Khrushchevism without Khrushchev,” that his successors were likewise conspiring with Washington to sell out north Vietnam and the National Liberation Front, and that this justified categorical refusal to engage in any united action against US military aggression in Southeast Asia.

Since that time relations between Moscow and Peking have steadily deteriorated until today they stand farther apart than ever with no prospect of reconciliation short of direct American assault upon China’s territory.

Meanwhile Peking has suffered an almost uninterrupted series of setbacks in the colonial countries. These began with the postponement of the Asian-African Conference scheduled for Algiers in June 1965 after Ben Bella’s overturn by Boumedienne. Peking received two black marks by its indecent haste in recognizing the new military regime and then by the nullification of the conference which it was eagerly promoting with a view to barring Soviet participation.

The intervention of the Chinese in various of the of the newly independent African countries have not met with much success, in part because of the reverses of the revolutionary forces on that continent highlighted by the suppression of the Congo rebels by the US-Belgian-South African mercenaries. Chinese representatives have been expelled from several countries (Burundi, Kenya). By the end of 1965 Peking’s influence in Africa had been largely reduced to the Congo Republic and Tanzania- and this June there was a reactionary army rising in Brazzaville.

The biggest blow came at the end of February 1966 when Nkrumah was overthrown while on his way to Peking.

In Latin America pro-Peking split-offs have been organized from the Communist parties in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Mexico. Many guerrilla fighters are inspired by the example of the Chinese Revolution, adhere to its ideas of colonial struggle, and look hopefully toward Peking for material aid. But it cannot be said that the Chinese have made sizeable headway at Moscow’s expense. Castroism remains the predominant influence within the revolutionary Left in Latin America.

In the past year and a half Peking’s influence in Asia has lessened. China won no laurels by its abortive mobilization during the India-Pakistan conflict. It has seen both North Korea and north Vietnam turn from sympathy to neutrality in the Sino-Soviet dispute and attend the Twenty-third Congress of the Soviet Communist Party in defiance of Peking’s boycott. Even the Japanese CP, irritated by Peking’s ultra-leftism and obstinacy in rejecting united action

of the Communist countries against US military escalation in Southeast Asia, is becoming alienated. Its daily newspaper has stopped publishing the broadcast schedules of the Peking, Hanoi and Pyongyang radio stations.

The military coup in Indonesia last October was the most severe setback for Communist China on both the diplomatic and party levels. The keystone of Chinese policy in Asia against Washington and Moscow was the close alliance with Sukarno. The shunting aside of the Indonesian head of state and the reorientation of the generals toward the imperialist powers have shattered this strategy and shifted the relation of forces in that part of the world to Peking’s disadvantage. Peking is left with no strong and reliable partners in the Afro-Asian bloc.

The bloody crushing of the Communist Party of Indonesia, the largest outside China and the Soviet Union, was a double blow. Though formally neutral, the PKI was actually one of China’s firmest allies in the tussle with Moscow. It was also held up as a prize example of the success of Peking’s line in “the third World.” The repercussions of its total annihilation, so completely unanticipated by everyone from Jakarta to Peking and Moscow, are still resounding throughout the Communist world as well as within the Chinese CP.

After this came Castro’s attacks upon Peking and closer alignment with Moscow. From the inception of the debate Havana was tacitly sympathetic with the Chinese positions on the colonial revolution and unbending opposition to US imperialism. However, Peking’s sectarian attitude in dealing with the neutrals in the Sino-Soviet conflict, coupled with Cuba’s inescapable economic and military dependence upon the Soviet Union, have nullified this sympathy.

For a time neutralist Rumania sought to play the role of honest broker between Moscow and Peking. Now the schism produced by Chou’s visit in June, either through the Chinese Premier’s intention to make a public denunciation of Moscow or opposing any concession to US imperialism in the Vietnam war, has left Peking virtually alone.

Its only remaining staunch supporters are Albania in Europe and an assortment of smaller Communist parties ranging from Burma, New Zealand and Australia to the Grippa group in Belgium. China can count on only half-hearted backing from north Vietnam and North Korea against Moscow.

This is not much to boast of after five years of bitter ideological struggle. The prospect of improved trade and diplomatic ties with Japan and other capitalist governments does not compensate for the accumulated losses on the world arena.

China’s growing isolation within the Communist bloc is all the more troubling in face of the tightening US encirclement and the relentless edging of its military machine toward Chinese territory.

Even a fissureless monolith would tend to crack under such stresses. A realistic view of China’s worsened international situation must be one of the principal generators of dissension at the top of the CP and its government. Prominent spokesmen have dismissed the reverses as unimportant and asserted that such temporary setbacks are inevitable on the road to complete victory. Such official optimism cannot squash all doubts. Some influential voices must be raising such questions as: How did we land in this plight within a year and a half after Khrushchev’s downfall? Can there be some flaws in Mao’s omniscience? What must be done to turn the adverse tide and break out of our isolation? Isn’t a new course necessary?

Such “dangerous thoughts” in high circles may very well have been major precipitants in the regime’s ongoing purge and its stiffening of thought control over the whole range of China’s intellectual and political life.

It is not so easy to discern the precise character of the difficulties in the economy and the remedies being proposed for them either by the government or the opposition. Although the worst damages suffered in the “Great Leap Forward” and the famine years have been repaired and the economy is moving ahead slowly, food production is only now approaching the output of 1956, while tens of millions more mouths have to be fed.

It has been reported that the government is considering agrarian reforms at the expense of the family income and private plots of the peasants and that there is fierce controversy over the allocation of the national budget for vast prestige projects as against investment in more solid enterprises. Certainly, discontents arising from the vital everyday interests of the great masses of peasants are among the touchiest issues since they are soon transmitted into the armed forces.

On one point there is little doubt. That is the intense yearning for greater intellectual, artistic, scientific, and even political, freedom.

However, the major factor in bringing differences to a head very likely comes from the relentless squeeze being exerted by the steady expansion of American military operations grimly emphasized by the bombing of the oil installations at Hanoi and Haiphong and Johnson’s bellicose declaration that his administration is determined at all costs to stop aid to south Vietnam at its source. If the Pentagon so decides, that source can be China as well as Hanoi.

The imperialist strategists included in their calculations of escalation both the division between Moscow and Peking and the internal conflict within the Chinese leadership.

Thus the Wall Street Journal reporter Philip Geyelin gave the following as part of the reasoning which lead to the attacks on oil storage depots near Hanoi and Haiphong, in a front page story from Washington, June 30:

“Much more than practical military need was involved in the decision, which has been the subject of intense deliberation for months ... To the experts, Hanoi looks to be increasingly isolated from its big Red patrons, Russia and Communist China, as these two concentrate increasingly on their own quarrel and the Chinese are convulsed by purges and internal strains.”

Washington knows more about the differences at the top in Peking than it says; for the moment it is being close-mouthed and very prudent in its comments, belligerent as its actions are.

There is much speculation that, in view of China’s need for aid in the face of the threat of US military assault, certain of its army strategists have been calling for reconsideration of government relations with the Soviet Union and an end to the refusal to enter into a defensive alliance with its leaders. The chief of the general staff, Lo Jui-ching, and some of his subordinates, have been ousted. An editorial in Liberation Army Daily said a big struggle took place in the armed forces during which “representatives of the bourgeoisie who had got hold of important posts in the army” were exposed as important members of “the counterrevolutionary, anti-party, anti-socialist clique recently censored by the party.” Among those may be the chief of the general political department, Hsiao Hua, and the commander of the navy, Hsiao Ching-kuang.

All the differences over these issues may be sharpened by the slackening of the aged Mao’s hand on the helm, despite the frenzy of the official idolatry.

It must be stressed that the rest of the world is at a loss to know just what the oppositionists stand or speak for, or even what matters are in dispute, because only the obviously distorted version given out by the regime is available.

The Mao leadership has insisted on thorough discussion and clarification of the questions involved in the Sino-Soviet dispute. Yet they keep everyone in the dark when it comes to the pros and cons of their vital decisions at home.

In this respect, Mao’s regime sticks to the accursed tradition of Stalin who instituted the anti-Leninist practice of restricting policy-making powers to a tiny group dominated by the arbitrary will of the unchallengeable individual. Everyone else at home and abroad was obliged to acquiesce in what emanated from the infallible leader.

How things stand in this respect in China is indicated by the fact that the Chinese Communist Party has not held a congress since 1958. So far as is known, the Central Committee has not met since September 1962!

Macpherson, Toronto Star, April 23, 1966 |

As a result of this authoritarian secretiveness, outside observers are reduced to “educated guesses” in analyzing and appraising the current political crisis. From the accusations against the dissident intellectuals and other sources, it is possible to discern the vague contours of their criticism and the trend of their thinking.

Taken together, these positions would constitute a serious oppositional program to the policies of the Peking leadership. It thus appears plausible that a serious struggle is being waged in the top echelons of the Chinese Communist Party over policy and perspectives and that the intellectuals under fire, and possibly the ousted military men, are tied up with an anti-Mao faction and reflect its views.

The publicly assailed writers, experts and scholars may be surrogates for the real targets in the commanding heights of the party and the army, embracing those dissidents who are discontented with the results of the foreign and domestic policy in recent years, have voiced opposition to them, and project an alternative course vigorously rejected by Mao and his men.

This surmise is substantiated in the warning given June 4 by an editorial in Jenmin Jih Pao, the CCP’s central newspaper, that even the oldest and highest leaders would be removed if they opposed Mao’s policies. The editorial declared:

“Anyone who opposes chairman Mao Tse-tung, opposes Mao Tse-tung’s thoughts, opposes the party’s central leadership, opposes the proletariat’s dictatorship, opposes the correct way of socialism, whoever that may be, however high may be the position and however old his standing, he will be struck down by the entire party and by the entire people.”

The identity of the highly placed “demons” and “monsters” in the party and army against whom these warnings are directed has not been disclosed. There has been considerable speculation in the world press about the shifts of power among the men at the top but no definitive information. The New York Times has reported, for example, that Defense Minister Lin Piao is the chief promoter of the purge and has become the “most powerful man in the country.” The posters which have been put up coupling his name with Chairman Mao’s would seem to bear out this supposition.

On the other hand, Liu Shao-chi, chairman of the Chinese People’s Republic and a long-time associate of the purged Peking Mayor Peng, has not been heard from during the current struggle. But the internal struggle is not ended and it remains to be seen who its ultimate targets are and what its outcome will be.

To avoid misunderstandings, it is essential to make clear the political attitude of the Socialist Workers Party toward the People’s Republic of China. We believe that the Chinese revolution was the greatest blow against capitalism since the October 1917 revolution and that it is a continuation and extension of that first socialist victory. Since 1949, we have been firm partisans of revolutionary China, defenders of its economic foundations and socialist advances against all internal and external enemies.

The Chinese revolution, now 17 years old, has immense achievements to its credit. It converted China from a capitalist-colonialist country to a workers state by overthrowing the Kuomintang dictatorship, ending imperialist domination, unifying the nation under a central government, wiping out provincialism and landlordism, nationalizing the land, banks and major means of industrial production, monopolizing foreign trade, planning the economy, and reorganizing agrarian relations through a series of steps culminating in the People’s Communes.

The new regime has taken measures to improve food, clothing and shelter for the masses under extremely adverse conditions. It has stabilized the currency, cleaned up prostitution and beggary, promoted literacy, education and science, expanded public health and medical services, introduced social benefits for the aged and disabled, broken down the patriarchal family, given greater freedom to women, and opened vast vistas to the younger generation. This remarkable progress in so many fields testifies to the enormous popular enthusiasm and energies released by the worker-peasant revolution.

The Socialist Workers Party has demonstrated its solidarity with revolutionary China, not only in words, but in deeds: first in the struggles against Chiang .Kai-shek, then by our opposition to the Korean war, by our support to the workers state against Nehru’s bourgeois government in the India-China border clash, and now by our opposition to US intervention in Vietnam. Our 1964 national election platform favored recognition of China, the end of the blockade, and its admission to the United Nations.

But we also believe that the political system of the People’s Republic has been subjected to grave bureaucratic deformations arising from China’s poverty and cultural backwardness and reinforced by the Stalinist background, training and methods of the Mao leadership. There exists a workers state but not a workers and peasants democracy in China.

We Trotskyists are not blind followers or cheerleaders for the heads of any of the existing Communist governments: Kosygin, Mao, Tito, or even Fidel Castro, who is by far the best of the lot. We take the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth as our guide. In arriving at our positions, we start from the facts analyzed with the methods of Marxism and appraise them from the standpoint of promoting the international revolutionary struggle for socialism.

When any workers government or party is in error and, in our opinion follows a policy injurious to the welfare of the working people and the world revolution, we say so without fear or favor. For instance, we have taken an independent Marxist stand in the Sino-Soviet dispute. We maintain that Peking is in the main right against Moscow on many problems of international politics and especially, in condemning its complicity with Washington to implement the line of peaceful coexistence with imperialism. But we hold that Peking is wrong in exalting Stalin, retaining Stalinist ideas and methods, and characterizing Yugoslavia as a capitalist country.

Long before the tragic butchery of the Indonesian Communists last October, we stated that the Maoists were wrong in backing up the Indonesian CP’s subordination to Sukarno because its leader, Aidit, favored Peking in the dispute with Moscow and Sukarno was a diplomatic ally. Let me quote from our criticism of Peking’s position published over three years ago in April 1963:

“Although the Chinese Communists attack political submission to the colonial bourgeoisie, they are not consistent in this regard. For example, they do not object to the craven support given by the Indonesian CP to the government of Sukarno who is Nehru’s counterpart in that country. It appears that, even in the colonial sphere, Peking’s principles are tailored to fit the momentary needs of its foreign policy.” (Moscow vs. Peking, The Meaning of the Great Debate, by William F. Warde, Pioneer Publishers, New York, p.10.)

The Maoist support to the line of class conciliation in Indonesia resulted in a re-edition of the catastrophe suffered in 1925-1927 by the Communist movement itself in China.

Now Peking’s stubborn refusal to participate in a united front with the Soviet Union and other Communist countries in defense of Vietnam threatens to give the world a re-edition of the defeat inflicted on the German working class by Hitler in 1933.

What is at stake in the present situation? Washington’s war machine has intervened to try to crush the Vietnam revolution and terrorize and pulverize north Vietnam while it threatens to invade China and wipe out its nuclear installations. For its own security, if nothing more, the Chinese leaders should press for the broadest cooperation amongthe workers states against the imperialist aggressor, as almost every other Communist government and party has recognized, and as many Chinese Communists must be thinking, if not saying.

Yet Peking scornfully rejects united action with Moscow on the specious ground that its revisionist heads are in collusion with Washington. Because of its timid response to the escalation of US belligerence over the past two years, the limited supply of arms it has sent to north Vietnam, and its refusal to give an unmistakable public pledge of support to China in case of an American attack, the Soviet leadership cannot be absolved from responsibility in encouraging imperialist aggression in Southeast Asia.

But the most effective way Peking could expose and demonstrate any such complicity on Moscow’s part would be an unremitting campaign for a united front between the Soviet Union and China which would issue a solemn “cease and desist” warning to the Washington warmakers.

Instead of such a Leninist policy, the Maoists content themselves with denouncing the “modern revisionists” and the “enemies-of-Mao-who-hide-behind-the-thought-of-Mao.” The Chinese press exhorts the Vietnamese to fight on valiantly by themselves and, in defiance of the facts, claims that the war is proceeding from one success to another. Johnson and the Pentagon are the sole beneficiaries of this blind attitude.

This sectarian course bears the gravest resemblance to the policy imposed by Stalin on the German Communists during the rise of Hitler. The German CP rejected united action of the Communist and Social Democratic parties and trade unions against the Nazis because it viewed the Socialists as “social-fascist” accomplices of capitalist reaction. Thanks to this suicidal policy the Brown Shirts marched to power through the divided ranks of the German working class and the Third Reich went on to prepare for the Second World War and the assault on the Soviet Union.

What happened on a national level in 1932-3 is now being duplicated on the international level in 1965-6 – and the consequences of this disunity for the cause of world socialism can be no less disastrous.

We American socialists who live in the bowels of the imperialist monster which is stepping up its military operations in Southeast Asia and menacing the borders of Communist China have special obligations in the present situation. As the Marxist wing of the antiwar movement, we have to intensify our efforts to oppose and stop Johnson’s dirty war in Vietnam with its danger of dragging the American people into a nuclear conflict with China.

At the same time we have a responsibility to the revolutionary Communists, intellectuals, students and youth in China who are being unjustly victimized and slandered for demanding more freedom of thought and expression and the rectification of errors committed by the present leadership. We are on their side in the struggle for greater democracy and a more correct course.

To combine these two tasks into a single policy and to understand their dialectical interrelation is what distinguishes a genuine from a would-be Marxist-Leninist in regard to the current political crisis in China.

1. This article is the substance of a speech given at the Militant Labor Forum in New York City July 1, 1966, representing the view of the Socialist Workers Party. It was the first public talk on this subject by any radical group in the United States.

Last updated on: 12.2.2006