The basic concepts from which we start are therefore first of all those of act

and capacity in their dialectical connection: the

act presupposes the capacity (absolutely speaking from the ontogenetic starting-point,

then relatively) and the capacity itself increasingly presupposes the act, which

can be divided into manifestation and production of capacities (sector II and

sector I of activity). But an act is not only the use of a capacity, whether

a direct capacity or a capacity to acquire new capacities: it is also the movement,

the practical mediation from a need to a product in the psychological sense

of the word – the vice-versa. First of all, from the ontogenetic starting-point,

the act expresses the need of a product; then, increasingly, it produces the

need. The relation of the product to need, P/N, which partly, but only partly,

corresponds to the conventional present-day psychological notion of motivation,

and in which the product as the numerator occupies the determinant position

from the point of view of instigation to the act, constitutes a third basic

concept. But while they must intervene as basic elements in the general topology

of the personality and in the theoretical construction of a singular biography,

these concepts by themselves are still far from providing us with the basic

structure which we are seeking: on the contrary, if we take them in isolation,

as we have been forced to do at least in part so far, they are strictly speaking

incomprehensible. Thus the act is only a moment of overall activity. Capacity

immediately refers to sector II, the temporal relations of which with sector

I present the question of the general structure of activity. Still more essentially,

if it is possible, the relation P/N, and each of its terms taken separately,

imply the structure of the personality in its entirety, of which they appear

to be partial expressions. Everything leads us therefore to present the decisive

problem on which constituting a science of personality above all depends: the

problem of the structure of basic activity, the infrastructure of the personality.

Let us emphasise first that the infrastructure of the developed personality as it emerges particularly at the end of childhood at the time of the transition to adulthood and in adulthood itself, is necessarily the structure of an activity. Certainly, one can undoubtedly speak about structures of the individual which in themselves do not belong to this activity and indeed which are essential to it as formal conditions; such, it seems, is the case of nervous types in the Pavlovian sense. Precocious structures also undoubtedly exist which are constituted on the basis of specifically infantile activities, and which are so many preliminary materials for, but at the same time obstacles to, the formation of the developed personality; from our point of view, such is the case of character in the sense in which Wallon studied its development in children, the structuration of the child’s psychic apparatus – conditional upon what one may consider to be established by psychoanalysis. The present enquiry into the infrastructure of the developed personality, i.e. in fact, the personality proper, rejects none of these facts a priori but its object is quite different: what is specific about it is that it sets out from a domain which until now has never been dealt with scientifically in proportion to its importance: the system of acts, the content of the biography. It therefore goes to meet the psychological works which bear on the other elements of structuration, both to incorporate those results which concern it and reciprocally to suggest to them the reasons for their impasses and possibly the way to surpass them. But it also implies the firm belief that it is only on its terrain that the root of the problem of the personality strictly speaking can fmd its solution, because it is there that the essence of human life comes into play and crystallises.

But to conceive the infrastructure of the personality as the structure of an activity is necessarily to conceive it as a structure the substance of which is time, as a temporal structure, for only a temporal structure can be homegenous with the internal logic of an individual’s activity, with its reproduction and developmnent. Despite their profound differences, typologies or characterologies, theories of cultural models, field dynamics or psychoanalysis have this point in common, that the structures which they consider are non-temporal structures. Some, if they claim to deduce from them the structure of the personality itself, involve the altogether rather naive mistake of imagining that the persistance of personal psychological characteristics through time can only be explained by way of a nature which in itself is invariant, which they assume to be biological, as if structural identity through time and the non-temporal character of the structure were identical. In that case, even biological processes would be inconceivable. Others, of a more genetic tendency, agree to the idea of a development, indeed an evolution of the structures of the personality, but this historicisation remains external and is based on structures which are essentially non- historical, structures for which time is merely the site of synchronic functioning but not of dialectical development. This is how the basic personality in cultural anthropology, or even the trinity of the id, ego and super-ego in the second Freudian topology, while presented as being genetically produced and as functional, are nevertheless conceived as non-temporal in themselves. What we are looking for, on the contrary, is the structure of activity itself, in other words, the dialectic of its development in time, which represents the unity of its functioning structure and its law of historical movement. And in addition, if this dialectical structure, i.e. the real activity of the concrete individual, is indeed what we are seeking, it is necessarily a reality which men constantly have to deal with in their life, therefore a practical reality, the empirical aspects of which are quite visible even if the elaboration of its theory and the construction of its topology present great difficulties. I put forward the hypothesis that this reality which is absolutely basic, and which in a sense has always been perfectly familiar, is use- time (l’emploi du temps).

The concept of use-time meets all the epistemological conditions which were put forward in the previous chapter and which have to be met for a science of the singular individual to be possible. A concrete temporal structure, use-time thus expresses the logic of a singular activity, a singular personality, but this logic is governed by the necessity for a general topology of use-time which it is the task of the theory of personality is to construct, thereby providing the empirical science of singular personalities with its basic principles. The extreme wealth of the material to be investigated under the rubric of use-time, the multiplicity and the importance of the questions related to the individual life which it becomes possible to approach rationally starting from the idea that use-time is the real infrastructure of the developed personality, becomes evident right away. But of course, for use-time to be a really scientific concept, it is essential not to confuse either phenomenal, empirical use-time as one may immediately represent it to oneself in the ideological categories of lived experience, nor superstructural, ideal use-time which an individual may have in view and even strive to achieve, with the essential, real use-time, i.e. the system of actual temporal relations between an individual’s vaniotjs objective categories of activity, for here, even less than elsewhere, can one judge an individual on the idea he has of himself; on the contrary, it is by starting from the scientific investigation of his real use-time, possibly unconscious or at all events mainly unconsidered, that one can try to account for the empirical forms of his life and of his conscious experience of them.

One can see, therefore, that the elucidation of real use-time depends on an absolute theoretical prerequisite, which is the scientific analysis of activity. Indeed, we have said, real use-time is the system of temporal relations between the various objective categories of an individual’s activity. But how can we identify these objective categories? It is clear that we will not possess a science of use-time and of the personality if we merely talk about an individual’s activity by referring to the categories of activity according to their immediate form in the sphere of lived experience. This is precisely the limitation of literary ‘psychology’, e.g. the ‘psychology’ to be found in novels, at least of the mediocre kind, as opposed to that found in the truly great works, the significance of which we will consider later. It was also the stumbling-block of the Politzerian attempt at a ‘dramatic’ psychology: how could one proceed to a concept and a theory of drama while remaining on the terrain of concrete biography? The answer to this question is that as a matter of fact one cannot go directly from one to the other by a short cut, as naively psychologistic humanism imagines, but rather through the detour of a science of human activity in its basic objective determinations. As Politzer had understood in i 929, without the conditions of that period enabling him immediately to turn this understanding to advantage, this science is political economy in the Marxist sense of the term and, more broadly, the science of history. It is only in so far as individual activity, instead of being taken in its experienced forms and considered as the direct effect of a falsely concrete, i.e. psychologised, human essence, is, on the contrary related beyond immediate appearances, to the social world in which it is carried out, and is rediscovered as a product of the structures of this social world, that the secondary classification of .dividual activity can be undertaken with some chance of success. Complex though it appears, this is a principle with regard to which any simplification , any weakening, any lack of vigilance, results in ending a lot of effort going round in circles: entire libraries of pseudo social psychology, which are the graveyards of the ‘scientific’ productions of speculative humanism, are there to prove it.

In this connection it may be useful to point out that while the concept of use-time put forward here appears open to empirical investigations at the level of real biographies, investigations which sociological works on time expenditure (le budget-temps) help us to envisage, the confusion of these two concepts would nevertheless be disastrous. It is well known that recent years have opened up comparative investigations on workers’ time-expenditure in capitalist and socialist countries, investigations from which numerous writers have imagined it possible to draw the conclusion that nothing resembled the time-expenditure of a worker in a capitalist factory more than the time-expenditure of a worker in a socialist factory. It is not our intention to discuss here the concept of time-expenditure underlying this result from the sociological point of view, even though its agreement with the fundamentally mystifying thesis of the unity of ‘industrial society’ behind the diversity of the social systems through which it develops cannot but make one reflect. The only thing which is important to us here is whether the principle on which the sociological investigation of time-expenditure is founded, and which leads to distinguishing essentially four headings, (labour-time in production, time for domestic pursuits, time for satisfaction of physiological needs, leisure time), is acceptable from the point of view of the psychology of personality. The answer is obviously no. While it might be permissable from the sociological point of view to classify under the same heading of labour-time in production both alienated labour, provided by a worker in selling his labour-power as a commodity that produces surplus-value for a capitalist, and socially emancipated labour (which does not mean labour freed from every constraint) for which a worker in a socialist society receives a share of the social product proportional to the quantity and quality of the labour provided, so that eight hours of social labour of a metal-worker in Gorki are sociologically equivalent to eight hours of social labour of a metal-worker in Detroit, this represents in the psychological perspective defined earlier at length, a simply absurdity. For even before having elaborated the topology of use-time, one can easily grasp that alienated labour, of which the order of magnitude of the psychological product is determined in advance by the value of labour- power, i.e. by the commodity form of the personality, and emancipated labour, of which the order of magnitude of the psychological product determines itself in the actual labour-process, individually as well as socially, cannot, other things being equal, have analagous relations of P/N, nor could they have similar roles to play in the production of capacities and the reproduction of the whole personality. Time- expenditures are quantitatively commensurable, use-times are qualitatively opposed: from the psychological standpoint, the former do not go beyond a use-time which is still apprehended in empirical terms, whereas the latter reflect the real infrastructure.

The crucial problem for the theory of use-time is therefore first of all the identification of those psychological activities which must be considered to be objectively infrastructural. I propose the hypothesis that they are all the psychologically productive activities, meaning by that the ensemble of activities which produce and reproduce the personality in whatever sector. Defined like this, infrastructural psychological activities on the one hand leave out natural biological functionings, even the most essential (breathing, for example), which do not constitute psychological activities strictly speaking, and on the other, superstructural activities in the broadest sense of the term, i.e. all the activities which are not psychologically productive but organisational or simply derivative at any level whatever (e.g. reflection on ideal usetime). This hypothesis is the only one which is consistent with all the phenomena considered above: if the developed personality is essentially activity, basic activities are all those which produce and reproduce the personality. It is psychological production and not need that distinguishes the infrastructure: here one can undoubtedly see to what extent the long critical analyses of this concept of need were necessary. The range of infrastructural activities being circumscribed, what objective categories of activity can one identify? This question is as decisive for the theory of personality as the identification of social classes is for the science of social formations. But, as a matter of fact, as we showed as early as Chapter 2, at the same time as historical materialism provides us with the theory of social relations it provides us with that of the forms of individuality, in other words the objective social conditions of the activity of individuals who correspond to them. In their topology the infrastructures of personalities necessarily reflect social infrastructures: this statement is nothing other than the projection of the 6th Thesis on Feuerbach into the conception of the concrete individual. Therefore there can be no question of a universal topology of ‘the’ human personality. At the level of approximation at which these few extremely schematic hypotheses are put forward, it will be enough here to suggest the general shape which this topology seems to have in a society in which capitalist relations predominate almost universally, as is the case in France in the stage of State monopoly capitalism.

In most individuals (not in all), the ensemble of psychologically infrastructural activity is dominated by the opposition between activities of socially productive labour on the one hand, and activities directly relating to oneself on the other, with various other activities occupying a complex position between these two basic categories. To prevent the most serious misunderstandings it is of exceptional importance not to confuse the classic, if not always well-understood, Marxist concept of socially productive labour, which we use here to designate one fundamental category of basic psychological activities, with the notion of psychologically productive activity, suggested above as a new linguistic usage to designate on the terrain of psychology the ensemble of the infrastructural activities of the personality. And in a sense, all the essential contradictions of the topology of the personality in capitalism result precisely from this distinction. In capitalism, as Marx showed forcefully,‘productive labour is that which alone produces capitital’.

That labourer alone is productive, who produces surplus-value

for the capitalist, and thus works for the self-expansion of capital. If we

may take an example ... a schoolmaster is a productive labourer, when, in addition

to belabouring the heads of his scholars, he works like a horse to enrich the

school proprietor.

A writer is a productive labourer not in so far as he produces ideas, but in

so far as he enriches the publisher who publishes his works, or if he is a wage-labourer

for a capitalist.

In other words, the nature of capitalism is that only labour which assumes the abstract form, and in so far as it assumes this abstract form, tends to function as socially productive labour. Concrete labour, as concrete, at the very most may give rise to direct exchange or provision of reciprocal services which cannot create surplus-value and therefore produce capital. This is precisely one of the most obvious forms of the alienated character of social labour within capitalist relations, since the productive character which labour possesses as concrete human activity is only socially recognised through its opposite, labour in its dehumanised abstract form.

Thus we can briefly describe the personal activity of socially productive labour (in the capitalist sense) as abstract activity –– although naturally it also has a concrete aspect – since it is as abstract labour that it is socially productive, and this also constitutes what is essential in its psychologically productive character: it is above all through the purchasing power of wages that wage-labour intervenes in the production and reproduction of the personality. And we shall call concrete activity all personal activity which directly relates to the individual himself, for example aus directly satisfying personal needs learning of new capacities unconnected with the carrying out and requirements of social labour. Between these two massifs of the concrete personality and the abstract personality generally extends the diversified ensemble of more or less intermediary psychologically productive activities, concrete activities which tend to be assimilated by abstract activity, such as for example, personal training or leisure activities being assimilated to efforts to compensate for the moral depreciation of the value of labour-power, the lowering of its social position; and on the other hand, formerly abstract activities which begin to function partly as personal satisfaction of needs, for example do-it- yourself work, etc. But besides all these sorts of activity, which are intermediary as it were contingently, it is necessary to consider activities which are intermediary in essence – interpersonal relations and above all, domestic relations. The psychologically productive activities which unfold on this terrain of familial relations differ profoundly from concrete activities relating immediately to oneself in that, since they essentially involve relations with others, this implies that the activity takes on a double aspect, as every exchange does: in the provision of the simplest service, the act on the one hand is an individual’s but on the other it is also an act for others, at least partly necessarily determined by the conditions of the exchange, by the objective relations of the couple, the family. In short, we are now dealing with a supraindividual logic of activity, with the specific contradictions which this involves. However, this is a radically different logic from that which we met with in investigating socal labour strictly speaking, which rests directly on those relations which are decisive in all respects: the social relations of production.This means in particular that the most fundamental phenomena from the standpoint of the specifically capitalist topology of the personality, i.e., the transformation of a central part of man into a commodity, and of concrete activity and concrete personality into abstract activity and abstract personality, occur only on the terrain ot social labour, or at all events immediately originate from this terrain. In the exchange of acts within domestic life, within the couple, the logic of the exchange does not by itself transform psychological activity into abstract activity. From this point of view, the essential dividing line passes between social labour and abstract personality on the one had, and on the other all the rest of psychological activity which remains concrete, whether in direct relations with oneself or in interpersonal exhanges. It would no doubt be highly instructive, moreover, to study closely the problems of tracing this dividing-line, as well as the secondary effects brought to bear on the intermediary categories by the two basic groups of activity.

In the concept of it that we propose here, use-time, the infrastructure of the personality, is therefore the temporal system of relations between the two broad categories of activity, i.e., essentially, concrete personal activity and abstract social activity. It is only if one adopts this global point of view of real use-time that one can fully understand the problems evoked above at the level of the analysis of the basic elements, and can see others appear which the investigation of the initial concepts separately did not yet reveal. Thus consideration of use-time makes it possible to grasp the nature and importance of a need which is absolutely specific and which is inconceivable on any other basis: the need for time. We have here, characteristically, one of those needs produced entirely by the development of the personality and which consists of a structural effect of use-time, i.e., produced in the last resort by the objective position of the individual in a determinate system of social relations. The need for time is the eruption of the contradiction between the needs and the conditions of activity, the general background to which is the opposition between the limitations of individuality and the inexhaustible character of the social heritage, which appears in capitalism in the form of the manysided conflict between the logic of development of the concrete personality and the constraints of the abstract personality, and between the various aspects of the abstract personality itself. Thus a crucial need for millions of men, and still more of women, is that of time for living (temps de vivre). Looking at it in simple-minded terms such a need is absolutely enigmatic in so far as ‘time’ is equally twenty-four hours a day for all human beings. Here one can see strikingly why a possible solution to the problems of the theory of the developed personality only exists ‘from above’, on the basis of the concrete whole that it constitutes, and not ‘from below’ on the basis of ‘simpler’ elements drawn from the sciences of the psychism or from childhood phenomena. The need for time for living is only comprehensible if one is able to account theoretically for the radical difference which exists between time-to-belived (temps a vivre) and time for living (temps de vivre), a difference which is by no means a psychic given but a social result affecting the personality to its core. To demand time for living in practice – the practice of the workers’ movement, in the school of which the science of personality has so much to learn – is to criticise the separation between abstract personality and concrete personality which capitalism carries out in our very soul with an invisible knife, to criticise a mode of life which requires the sacrifice of concrete personal life to abstract social life and abstract social life to the requirements of the ceaseless reproduction of the whole system.

More extended analysis of the effects of this need for time, which there can be no question of undertaking here, helps us to understand concretely how use-time subsumes all its elements, i.e. all the elements of the infrastructure of the personality. For if every act represents a certain physiological expenditure, it also presupposes a certain expenditure of psychological time. Now the total disposable psychological time in a day, a week, or a year is finite, so that the importance of the expenditure of time required by an act is not only determined by the absolute magnitude of this time but by the corresponding density of use-time. There would be room here for a marginalist type of analysis: the marginal utility or disutility of an act or of foregoing an act depends on the total activity. One can see that the composition of the psychological product of an act, considered as its time cost, is closely related, in this connection alone, to the place which it occupies in a concrete use-time, and that the real P/N, and therefore the actual incentive to an activity, is not the P/N of the act considered in isolation but a P/N mediated by the overall structure of activity. This, it seems, is an aspect of motivation in the adolescent and the adult which plays an enormous part in real life and which, however, entirely escapes the usual conceptions of the personality.

In the same way, the temporal conditions of simple reproduction and expanded reproduction of sector I and sector II of activity present problems which cannot find a solution if one does not state them by way of use-time considered in its entirety. Thus through a direct necessity, with which economists have become very familiar in the treatment of the homologous problem of growth-rates, the increase in learning of new capacities, simplifying in the extreme an~i taking all conditions to be constant, requires an increase in time set aside for sec:or I of activity and consequently a decrease of time available for sector II. One can glimpse the chain of innumerable effects and secondary contradictions which this presupposes. All these negative effects have repercussions on the real P/N of the additional activities of learning and at the level of lived experience may be expressed in an aversion to progress, from which one can guess what psychologistic or physiologistic ideology would be able to conclude. There are huge undeveloped problems here which we shall reconsider somewhat in connection with the laws of development of the personality. At all events, it appears legitimate to conclude that the investigation of use-time presents the features required for a scientific approach to the infrastructure. Economy of in both senses of the word economy, is clearly the key to the developed personality. Here, it is true, we are in the midst of theoretical from the psychological point of view; but, highly remarkable, at the same time we are at the heart of the Marxist science of society, i.e. of social man. And in a sense, all the foregoing is only a broad commentary on this analysis in the Grundrisse,

The less time the society requires to produce wheat, cattle, etc., the more time it wins for other production. Just as in the case of an idividual, the multiplicity of its development, its enjoyment and its activity depends on economisation of time. Economy of time, to this all economy ultimately reduces itself. Society likewise has to distribute its time in a purposeful way, in order to achieve a production adequate to its overall needs; just as the individual has to distribute his time correctly in order to achieve knowledge in proper proportions or in order to satisfy the various demands of his activity.

This last sentence, which there is no need to force in order to see in it the central role of personal use-time, shows at what a deep level the psychology of personality and the science of social relations are articulated, and to what extent Marxism is a fruitful basis for a science of man.

But, all things considered, what is important to us is not simply to identify and describe the infrastructure of the personality; it is above all to locate its principal contradictions and thereby to have access to its laws of development. Let us therefore bring together the various facts which we have already encountered concerning the central contradiction of the topology of activity in the conditions of capitalism. This contradiction can be summed up like this: the scission between concrete and abstract personality opposes psychological activity to itself and imposes a mode of development on it which encloses it within almost impassable limits: as a result all personalities formed on the basis of capitalist relations have a common topology, but the diversity of concrete conditions through which this appears and the forms of contradictory development which it assumes are inexhaustible. The concrete personality first presents itself as an ensemble of personal, indeed inter-personal, non-alienated activities, unfolding as self- expression; but, without examining here the historical process of which it bears the scars, the general rule of capitalist society is that the concrete personality is both cut off from social labour and essentially subordinated to its products, i.e. to the abstract personality,which more or less severely besets it, assails it, overwhelms it and crushes it, not only from without but from within. Abstract activity, on the contrary, presents itself right away as alienated activity, subject to external necessity, more or less estranged from the aspirations of the concrete personality; and yet it is in abstract activity that the individual is face to face with the developed productive forces and social relations, the vast means created in the course of human history to dominate nature and organise society – in a word, the sound heritage, the main part of the. real essence of humanity, i.e. it is activity in which the individual ought to be able actually to appropriate the human essence. This contradictory relation, which one rediscovers in all kinds of ways within particular biographies produced on the basis of capitalism, defines the closed circle of their use-time. The conditions of development of the concrete personality essentially depend on social activity, and therefore on the abstract personality, but the latter, far from making available the social conditions of full development which are generally lacking to the concrete personality, is merely the appendage, or at all events the instrument, of capital: thus the two men who dwell in every individual are each the alienation of the other; and to live in these conditions always therefore presupposes relinquishing some reason for living. Such a topology does not exclude the possibility of personalities of a certain greatness but it is always the greatness of an antagonistic contradiction.

To follow the internal movement of this contradiction in the concrete and singular forms which it assumes in each personality structured like this, is to trace on the theoretical level the moments of the cycle of use- time, to analyse the problems of balancing the psychological day, week or year, possibly to grasp the mechanism of the partial crises in which the principal contradiction periodically explodes without being fundamentally resolved. In short, it is already to confront the problem of the laws of development. Before coming to this point it is vitally important to note the essential differences which appear between the infrastructure of the personality as we conceive it here and the infrastucture of society as it is understood in Marxism, in order to forestall the possible temptaion to deduce too simply from the latter domain to the former. The first of these differences, from which all the others flow, is that the social infrastructure, the system of social relations, in the last analysis is determined by the character, the level of development of the productive forces. Certainly, numerous secondary or removed determinations come to modify this essential relation, but the infrastructure of a social formation nevertheless decisively derives from a determination internal to this formation. Things are different for the infrastructure of the personality. No doubt, on the one hand, the infrastructure appears as the expression of psychological capacities, i.e. as the product of a determination likewise internal to the personality; and in fact observation of biographies shows very clearly that when what a man knows how to do changes substantially, his use-time and personality are affected to their core. But it is in the nature of the individual to be also in a juxtastructural position in relation to society, i e. as a general rule it is impossible for him freely to change his use time as the increase in his capacities requires; on the contrary, the existing social relations impose from without a use-time, or at all events an objective logic of use-time, against which the individual will by itself is totally powerless. Here again, in different form, we come across the contradiction between concrete personality and abstract personality, which is also the contradiction between psychologically demanded use- time and socially necessary use-time. The excentration of the human essence is thus expressed in the excentration of the origin of use-time, but the exteriority of the origin does not mean that use-time is not an internal characteristic of the personality. This twofold contradictory determination, external and internal, is a specific property of human psychological individuality.

Another very important aspect of the differences between personality and social formation with regard to their respective infrastructures is the relative contingency of use-time as opposed to the broad historical necessity of social relations. In the development of a society social relations slowly form and change with the generations and through enormous numbers of productive acts, exchanges, superstructural interventions, etc., so that the consequence is a statistical result in which the dominant necessity carves its way in the midst of innumerable accidents. In an individual’s biography, on the contrary, the conditions of statistically eliminating the role of accidents are far from being fulfilled. Certainly, as we have seen, the limits of contingency within which the individual moves are themselves socially determined, but within those limits and particularly within the limits which capitalism fixes, the room for chance and thus for a formal freedom is not negligible. Social contingency in the determination of individual use- time appears to us to be an essential fact for the theory of personality and for the critique of the incredibly prolific ideologies which too often take its place, for example the ideology of ‘natural aptitudes’. Child psychology would possible benefit from searching in this direction too. If there is one thing which a child even of school-age, can hardly do, it is to structure his use-time coherently by himself; on the contrary, as soon as the externally imposed division of time is suspended for some reason and for whatever period his activity tends towards the most anarchic forms. This clearly shows to what extent use-time is an essential reality in the developed personality and at the same time what extent the origin of the developed personality lies out childhood. But this also helps us to understand the process throgh which the bases of the developed personality form in childrens’ relations with adults. While children are obviously not direct psychological images of their parents, on the other hand many things lead one to think that they might be rather like X-ray pictures of them, and even more than X-ray pictures taken of the parents separately they are like those of the couple which they form, of the family as a whole, and thereby of social relations. Is not the real use-time of the parents and of the family an essential element in this dialectical modulation of childrens’ nascent personality? The work of a Makarenko, in particular, constitutes a conclusive proof on this point.

Here we again meet with one of the fundamental bones of contention between the Marxist and the psychoanalytic conceptions of the personality. It has long been objected to the Freudian concept of the Oedipus complex, by Marxism and culturalism alike, that no Oedipal situation can exist in itself independently of the sociologically variable structure of the family. But to this objection, which has been standard since Malinowski ‘s works, the contemporary structural interpretation of Freud gives rise to the reply that,

the Oedipus complex is not reducible to an actual situation – to the actual influence exerted by the parental couple over the child. Its efficacity derives from the fact that it brings into play a proscriptive agency (the prohibition against incest) which bars the way to naturally sought satisfaction and forms an indissoluble link between wish and law (a point which Jacques Lacan has emphasised). Seen in this light, the criticisms first voiced by Malinowski and later taken up by the “culturalist” school lose their edge. The objection raised was that no Oedipus complex was to be found in certain civilisations where there is no onus on the father to exercise a repressive function. In its stead these critics postulated a nuclear complex typifying one or another given social structure. In practice, when confronted with the cultures in question, psychoanalysis have merely tried to ascertain which social roles – or even which institution – incarnate the proscriptive agency, and which social modes specifically express the triangular structure constituted by the child, the child’s natural object and the bearer of the law.

Such a reply undoubtedly has some validity against sociological and ethnological empiricism. But it does not meet what constitutes the ground of Marxist criticism. When Freud writes that ‘a child’s superego is in fact constructed on the model not of its parents but of its parents’ super-ego; the contents which fill it are the same and it otnes the vehicle of tradition and of all the time-resisting judgements ~value which have propagated themselves in this manner from generation to generation’, one can certainly state that to understand Freud clearly, one must not reduce the parents’ super-ego simply to concrete psychological forms of their repressive relations with their children but identify the essential prohibitive law of which they are merely the empirical bearers. But in doing this one merely makes more obvious the reduction of familial and social relations to their superstructural aspect, the reduction on which the Freudian interpretation, and also the structural anthropology which takes it up again on its own terrain today, rest. A structural, non-empiricist concept of the super-ego and law is nevertheless still a non-materialist concept impregnated with sociological idealism, which presupposes as a back-cloth the reduction of society to the law, i.e., to certain of its superstructures, ethico-juridical institutions, ideologies, forms of social consciousness, taken independently of their economic infrastructure; the oedipal triangle, child-parent relations and the super-ego are themselves directly connected with this purely superstructural law independently of the infrastructures of the personalities and familial relations in question. In my opinion it is this flagrant absence of social, familial and individual infrastructures, in other words, of labour, which is masked in Freud by a typically pseudo-materialist biologism of instincts. In this sense, we may ask ourselves whether the nonbiologistic and structural reading of Freud which is offered to us today is not a sort of epistemological transference in which the psychoanalyst, even while having a presentiment of its impossibility, makes a final attempt to think what man is while doing without the fundamental services of Marxism.

At any event, the contradictory external and internal twofold determination, and the relative contingency of use-time find expression n the fact, once again quite specific it seems, of the multiplicity of use- times partially co-existing at the level of the infrastructure of the personality. If this fact is altogether correct, it would then be necessary to analyse acts and their P/N in an even more complex way than this has been done so far. Indeed, every act is part of a determinate use- time not simply through temporal position but in its inmost self: the particular relations which it exhibits between capacities, needs and products make it intrinsically dependent on the general system of these relations, and this is precisely what the use-time is, and within which it fulfils a function which is in no wise interchangeable. This is why going from one act to another may sometimes express not the division of activities within one use-time but the transition from one use-time to another. To our way of thinking this is not an arbitrary theoretical construction but a fact of which every individual has more or less intuitive experience. For example, it is commonly observed that have to choose between several acts which are important and urgent, but the very congestion of which makes the contradictions of the use-time to which they belong immediately perceptible, we may choose to carry out a different act which is neither important nor urgent and the P/N of which, within this use-time, is much weaker but which, in point of fact, expresses a change, or at least a desire to change, to a different use-time the general P/N of which, if it were possible, would be much higher. Studying these phenomena of oscillating use-times would possibly be instructive as far as the deepest consistency of personalities and certain aspects of their pathology are concerned. To ensure the dominance of a use-time of general P/N as high as the objective conditions make possible appears to be the most decisive psychological function of a life. On the other hand, chronic oscillation of use-time and constant ambiguity of acts seem characteristic of a personality which at least partially gives up under the excessively contradictory pressure of circumstances. And this last observation gives rise to the question which, from our standpoint, dominates the whole science of personality, that of the prospects for full development which are open to it: to what extent does the solution of its basic contradictions depend on the personality itself? If use-time is determined by capacities only within the limits which social relations. prescribe, is not the personality inherently unable to solve, by itself and in a truly basic way, its own problems? And is not the excentration of the conditions required to achieve this itself the source of the critical and revolutionary dynamism, in the broadest sense, which individuals are capable of displaying with regard to society? Once again we encounter that very remarkable proposition in The German Ideology: ‘to assert themselves as individuals’ the proletarians ‘must overthrow the State’. And thereby we stand on the very threshold of the problem of the general laws of development of the personality.

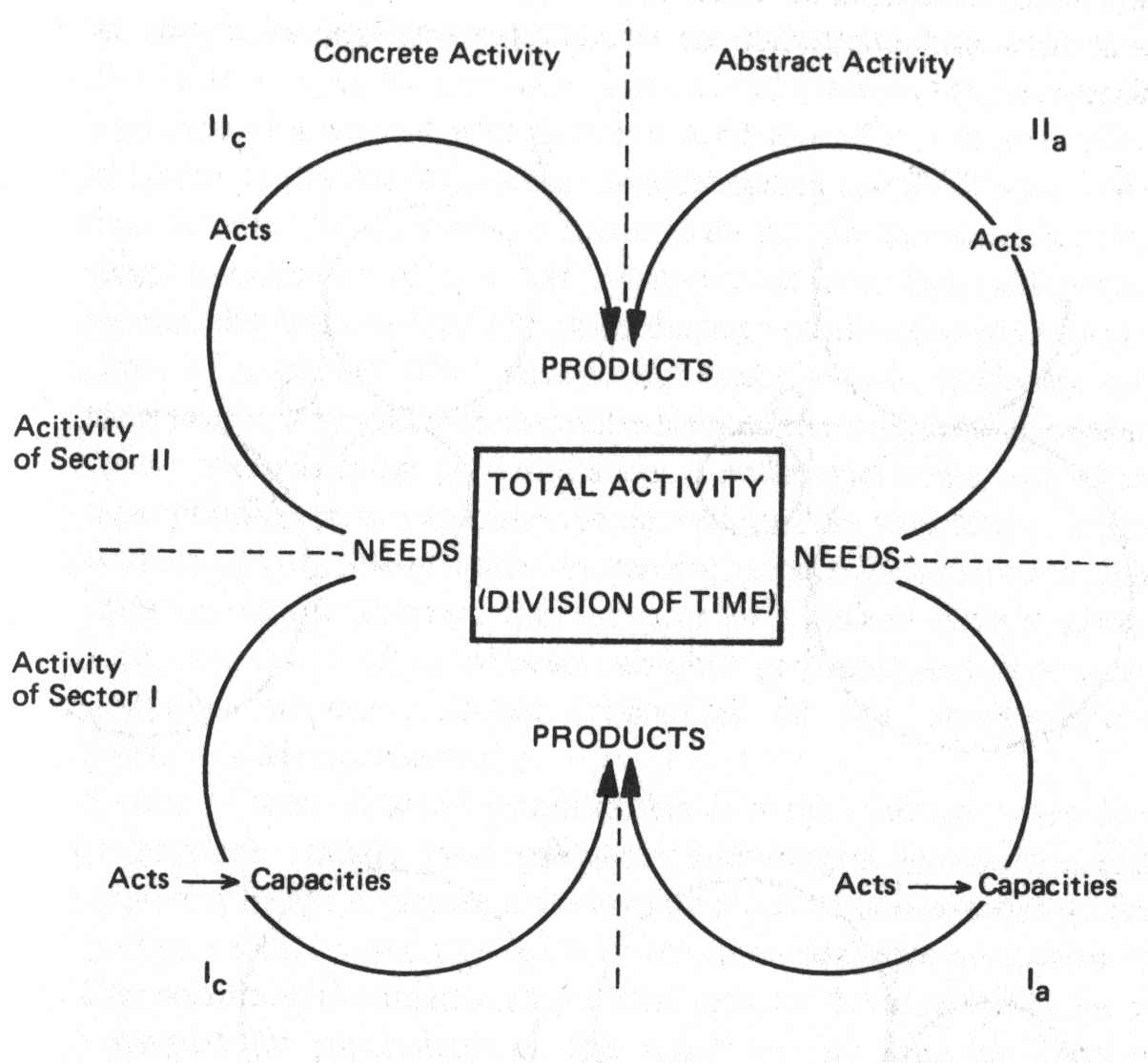

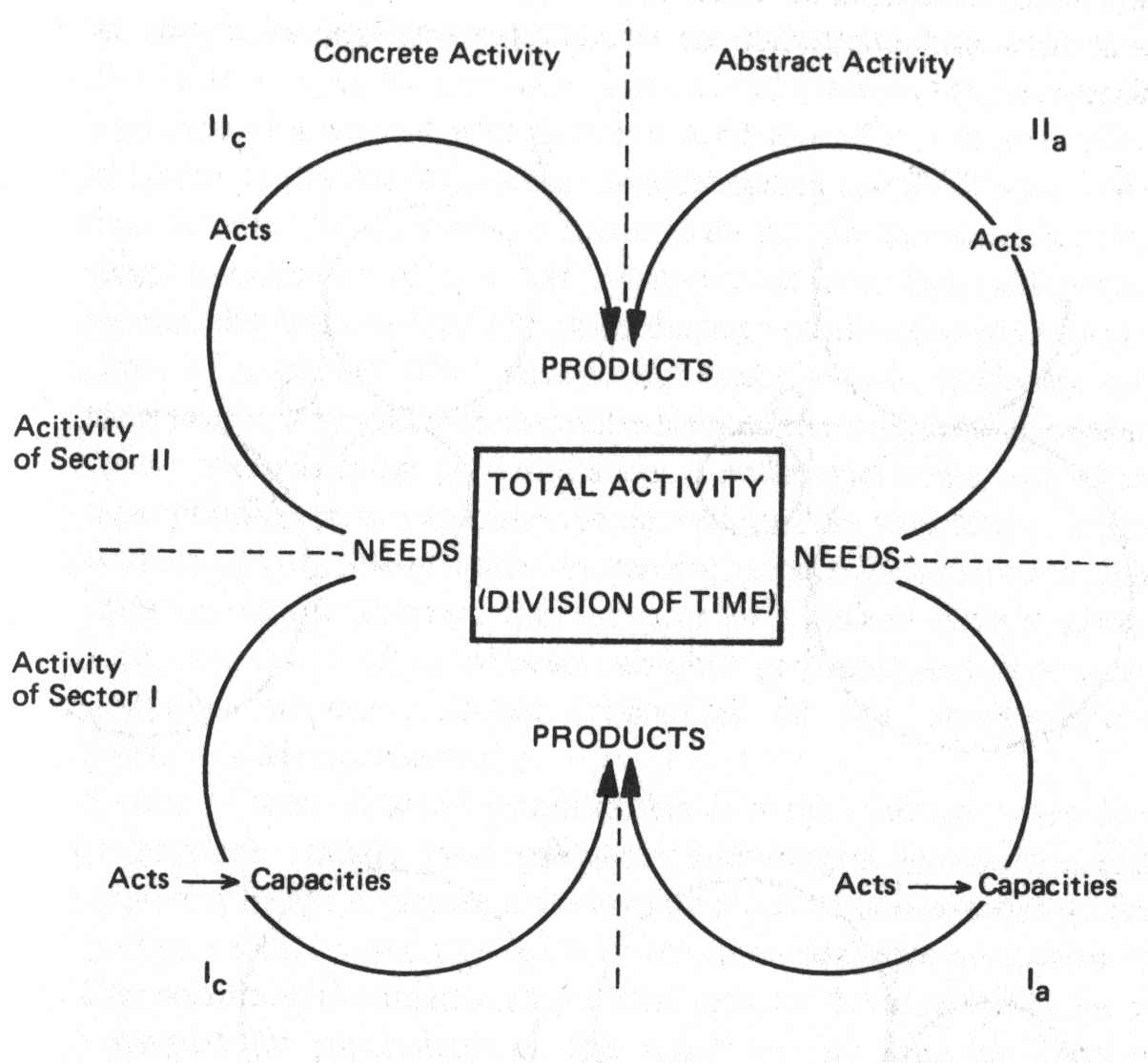

Thus, very schematically and hypothetically, but to our way of thinking fruitfully,

the topology of the real use-time, the infrastructure of the personality within

capitalist relations, seems to us to look like this – dialectical relation

of acts and capacities, of sector I and sector II of activity; constant mediation

from psychological needs to products and vice-versa in cycles which are determined

intrinsically through their integration in the general system of activity; then,

beyond intermediary activities, supporting and subordinating the preceding relations,

opposition within a living unity between the concrete personality, the of direct,

personal, and particularly consumer, activities, and the abstract personality,

the ensemble of social, but alienated, productive activities. If it is of any

interest, the general topology of activtity which we are seeking can therefore

be rigorously represented graphically as a complex interlocking of four basic

cycles:

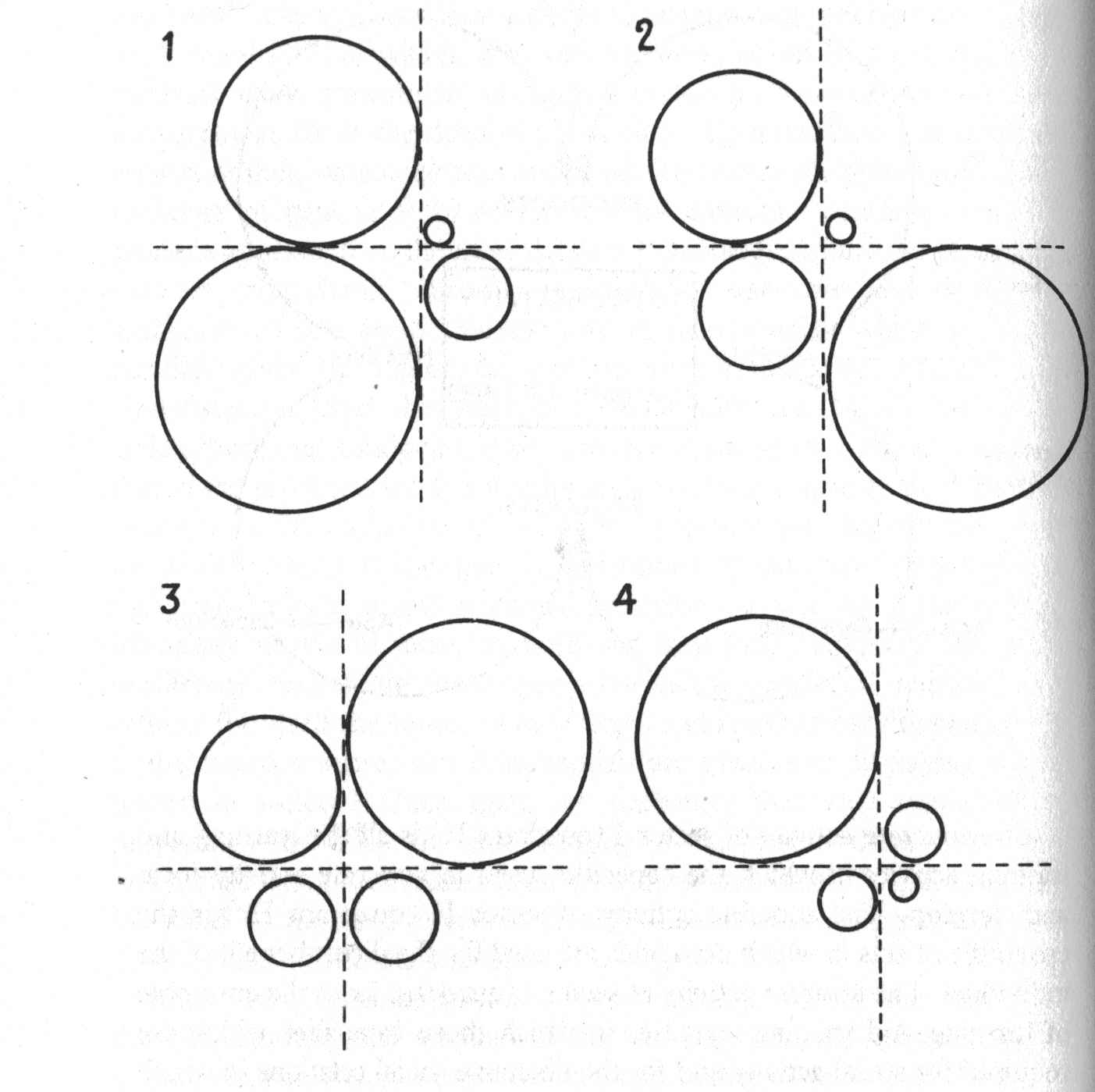

The concrete activity of sector I (quadrant 1c) is all the learning and training activity in which the capacities used in concrete activity form and develop. The concrete activity of sector II (quadrant 2c) is the ensemble of acts in which capacities are used for the direct benefit of the individual. The abstract activity of sector I (quadrant 1a) is the ensemble of learning and training activities in which those capacities which are required for social activity and for the objective social relations in which it is inscribed form and develop. The abstract activity of sector II (quadrant 2a) is the ensemblc of acts of which this social labour directly consists. Such a schema, it must be remembered, by no means claims to represent the personality of a typical individual. It corresponds to a hypothetical outline of the general topology of personalities produced within capitalist forms of individuality. Nevertheless, on the basis of this general topology it is clearly possible to construct the real use-time of a particular personality. But in order to do this numerous theoretical, methodological, and practical problems must still be solved, At the very most, by purely quantitative representation of the relative importance the four basic cycles, i.e. the percentage of total use-time which th represent, we can, in an extremely simplified way, suggest the variety structures and contradictions of real personalities as shown in the diagram.

These four diagrams do not illustrate a four term typology: we saw earlier that the conception of the psychology of personality upheld here exludes the very principle of a typology. They are simply four hypothetical examples, considered for their indicatory value, in themselves and in their relative variation. The first one might correspond to the use-time of a child of school-age: predominance of learning activities oriented towards the cycle of the concrete personality with a highly subordinate aspect of indirect preparation for social importance of concrete consumption acts, total absence of abstract activity, at the most taking part in the provision of domestic services : the virtual non-existence of the right hand side of the diagram, i e. of abstract activity, takes account of the fact that, in such a case, theory of the developed personality has as yet very little occasion to be involved with its specific approach. The second diagram might illustrate the use-time of a student who does not need to perform wage-earning social labour to pay for his studies: predominance of learning for future abstract activity, learning which secondarily has an aspect of concrete ‘earning, importance of concrete consumption activities, still virtual absence of abstract activity. The third diagram might correspond to the use-time of a worker who, outside his factory work, performs only personal leisure activities and domestic tasks to the exclusion of militant activities: overwhelming predominance of abstract activity, acquisition of corresponding new capacities being reduced to very little, limited importance of concrete activities in general, especially of sector I. The last diagram might illustrate the use-time of a retired elderly person carrying out a few small social tasks: absolute predominance of concrete consumption activities, drastic reduction of the other sectors, particularly of abstract learning.

In spite of their extreme simplification it is not difficult to see how these diagrams already raise problems and suggest investigations in connection with the structure and contradictions of personalities of this order. For example, one can see how the anti-clockwise succession of the four sectors of dominance may throw light on the question so far so little studied by psychology of the stages of life and the laws of psychological growth, the last two diagrams, in contrast to the first two, being clearly characterised by the drastic reduction of the two lower quadrants (sector I). Once one is used to reading the diagrams one can immediately see, for example, the phenomenon of capitalist exploitation inscribed in the very depths of the personality in the third diagram, in the form of an extreme predominance of quadrant hha (productive social activity) to which nothing comparable corresponds in the way of personal, concrete, consumption activities. Together with the collection of numerous essential biographical facts, much more complex representations based on first attempts at serious quantification and a sharpening of qualitative criteria may make it possible to initiate a process of effective scientific research.

Thus far we have only been concerned with a rough outline of the problematic of the infrastructure. But in our view the investigation of what may be referred to by the general term of psychological uperstructures promises to be every bit as fruitful. By psychological superstructures we mean the ensemble of activities which do contribute directly to the production and reproduction of the personality, but which play a regulating role in relation to the processes. By going from what is more to what is less immediate and narrowly subjective in this domain, one can first of all identify the manysided ensemble of spontaneous controls which are essentially of internal origin. This is the level of the emotions in the sense conferred on this notion by Pierre Janet’s analysis, mentioned above, of secondary actions, for example reactions to the cessation of primary action (reactions of triumph or failure). There is equally a case for investigating their connections with the psychoanalytic concept of unconscious controls. But it is also a matter, and first of all perhaps, of controls which so far have been investigated, no doubt because no psychological theory has made it possible to grasp them rationally: I mean to refer to this universal phenomenon, which is of paramount significance, the inclination (gout) immediately felt for this or that act and the lack of inclination, ennui, indeed the extraordinary passive resistence of disinclination (paresse) with regard to other acts. I put forward the hypothesis that, on the terrain of the dynamism of activity, this inclination and disinclination are the immediate expression of the quasi-ideological (in a psychological sense of the word) intuitive evaluations of the general P/N, the P/N of the use-time of the activities in question. Every individual is habituated to this intuitive evaluation which functions as steadily, for example, as perception itself, and a simple example of which is the very subtle and complex modulation of the inclination to get out of bed and of the ‘affective’ dispositions which result from this highly important act: without ignoring the strictly neurophysiological determinations and the often broadly constraining role of the social bases of use-time, is it not observable that an evaluation which is direct or which is at times arrived at to some extent by the anticipatory imagination, of the general P/N of the psychological day, typically intervenes here? The extended investigation of this form of psychological control would not only provide a valuable elucidation of this control itself but would also undoubtedly enable us to understand the nature and function of what we might call the optative use-time, the primary superstructural form of the use-time; and the analysis of the discrepancies, tensions and contradictions between operative use-time and real use-time could well be among the psychological investigations best able to reveal the actual foundation of a particular personality.

Apart from these spontaneous and highly endogenous controls of activity we must also consider the voluntary control through which a personality attempts to gain control over its use-time, i.e. depending on different cases and sectors, attempts to change it or, on the contrary, to maintain it. These voluntary controls are, for example, the rules of conduct that an individual endeavours to follow, the self-image which he projects, the deliberated use-time which he takes as a norm – superstructures which more or less elaborated and objective psychological ideologies correspond to and support. Generally these volutary controls have the distinctive characteristic of being, at least mainly, not endogenous but exogenous: at the level of the superstructures of the personality, as at that of the superstructures, social relations play an essential role of functional determination. However, it is advisable to be particularly careful here not to conceive this essential excentration of the voluntary superstructures of the personality in a way which would make one relapse into sociological idealism, for which society is above all constraining law and not in the first place relations of production. This misrecognition of the real basis of society results in masking the concrete class contradictions, society’s contradictions with itself, behind a speculative contradiction between the individual and the society. This being so, it is impossible to make ‘the will’ (in the usual psychological terminology) or better, the voluntary superstructures, in the concrete individual of capitalist society, appear as the result of a straightforward and direct interiorisation of the law, the institutions and the values of the corresponding society, without uttering a word about either psychological or social infrastructures.

What will always remain incomprehensible in such a perspective is the reason why individuals interiorise a law which, in relation to their aspirations, is itself purely fortuitous, external and constraining, and how they can go more or less from heteronomy to autonomy in observing this law. The example of Linton, led to postulate a ‘need for favourable response’ in order to escape from this insurmountable difficulty, clearly shows in what impasses one traps oneself on the terrain of the human sciences if one neglects the social infrastructures. Actually, in our view, the voluntary controls of the personality are not essentially formed through direct interiorisation of social institutions and values but through their assimilation on the psychological basis of the abstract personality. Very schematically, spontaneous controls may be considered as the superstructural instrument of the concrete Personality: for this reason they are fundamentally endogenous, like the concrete personality itself. Voluntary controls are the instrument of the abstract personality; they are therefore endogenous too, in the sense that they develop by way of a psychological basis internal to the personaljty. but at a deeper level they are exogenous, for the same reason depending on the same overall process as the abstract personality, i.e.. on the general basis of the juxtastructural character of individual life juxtastructural relation to social relations, and the incorporation of these relations and their contradictions into the personality through social activity and the corresponding use-time. The superstructural psychological contradictions between spontaneous and voluntary controls, between the desired act and the act which is required, are not original’ contradictions, as the mystifying ideology of the metaphysical contradiction between ‘nature’ and ‘culture’, ‘individual’ and ‘society’, imagines; beyond their relative specificity they are the reflection of the infrastructural contradictions between concrete and abstract personality, between self-expression and alienated labour, i.e. in the last analysis they also bear witness to class contradictions And the question arises whether the at least partial failure, not only of all classical theories of the ‘the will’, but even of the best informed research on the interiorisation of the law, from the psychoanalytic concept of the parental super-ego to Piaget’s works on moral judgement in the child, is not the, result precisely of the fact that, in spite of their extreme differences, all have failed to grasp the fundamental role in this connection of psychological and social infrastructures, in other words, once more, the fundamental role of labour.

But another basic problem of psychological superstructures is the level and value of consciousness of the self and the world which they make possible: does their psychological functionality condemn this consciousness never to be anything else in the last resort than a process of ‘rationalisation’ in the psychoanalytic sense, of ‘ideologisation’ in a sense derived from Marxism, i.e., a mystified interpretation of a reality the true nature of which remains misunderstood, thus enclosing man in illusion, alienation and dependence; or do they, on the contrary, precisely as a result of their functionality, make it possible, and under what conditions, to reach demystified self-consciousness, true knowledge of objective reality in so far as this depends on prerequisite psycho-epistemological conditions, and of freedom in so far as this depends on personal development? We will try to answer this huge question further on. But if, as Marx, and later in quite a different way, Freud, have taught us, the conquest of true consciousness over its opposite is very difficult, then we can tackle such a problem with some chance of success only by way of a truly scientific theory of lack of awareness (l’inconscience). Now it may seem remarkably bold to propose such a theory today (albeit with the extreme modesty of an indicative hypothesis) which does not at all refer to the Freudian science of the unconscious (1 ‘inconscient) and in fact questions its de facto monopoly in the matter. However, we do not altogether understand why the organised effort of the vanguard of the workers’ movement to promote the transition, repeated unceasingly in millions of men, from lack of awareness to class consciousness, from mystification by spontaneous illusions and dominant ideologies to political awareness, for example, should not in its own way constitute as valuable a basis as the analytic clinic for an attempt at a theory of lack of awareness, nor in what respect the delineation of a specific concept of the unconscious correspondmg to a historical materialist conception of the personality could be less permissable than that made by Freud with reference to a conception of the infantile development of the psychic apparatus.

The lack of awareness which we encounter on the terrain of the theory of the developed personality cannot at all be reduced to the neurophysiological fact that the conditions of consciousness are far from being mature at birth and that in every way their development is a long and complex process: without an unacceptable play on words, the mere absence, at some stage of development, of the forms and level of consciousness which will appear in a later stage, cannot be identified with the positive reality of a constitutional lack of awareness, just as one should not confuse a magnitude not yet measured with an unmeasurable magnitude. But as a matter of fact, beyond this simply relative and negative limitation of the field of consciousness, the basic structures of the developed personality appear to us to be dominated by a reality productive of a positive lack of awareness, namely the social excentration of the human essence. This excentration, the immediate consequence of which is that the circuit of acts goes enormously beyond the limits of organic individuality and beyond the field directly knowable by the individual, means even more that the capacity of social relations necessarily produces a corresponding opacity of the relations constituting the personality. Thus we showed earlier how fetishism of psychological functions and of the personality itself corresponds to what Marx analysed under the name of commodity fetishism, through which, in a commodity economy, particularly as predominant as it becomes with the rise of capitalism, relations between men are hidden from view behind relations between things, and this not at all through a wholly subjective phantasmagoria which scientific awareness is enough to dispel, but as an objective illusion inscribed in the abstract form, and therefore in the actual reality of social relations, an illusion which it will only be possible to abolish along with these relations; similarly the illusion of the movement of the sun in the sky depends on the objective conditions of the terrestial perception we have of it, and has not been abolished by Copernicus’ theory. All the illusions of vulgar psychological naturalism, of which abstract humanism is the elaboration at the level of philosophical ideology, thus have their origin in the objective characteristics of class society and their significance is basically no different from that of religious illusions, the links of which with commodity fetishism were shown by Marx. This false consciousness of the self and of man does not merely oppose the screen of obviousness to the analysis of real relations but, being at the same time an ideology justifying alienating social conditions and the corresponding forms of use–time, it manifests a resistance to occasions and attempts at demystification, a resistance characteristic of its superstructural functions. The rapidly impassioned turn often taken by critical discussion with defenders of ‘natural aptitudes’ is a good example of the underlying biographical meaning of these resistances: for many men the transition to true consciousness of the conditions of their own making or of that of those who are close to them would directly question the very bases of their life.

We are therefore dealing with a real constitutional lack of awareness of individuals with regard to the objective bases and productive processes of their own personality: for his part capitalist man is not immediately transparent to himself, anymore than capitalist society comes into existence with a true self-consciousness. Nevertheless, basic differences exist between this essentially historical lack of awareness and the Freudian unconscious. Thus the lack of awareness to which we refer does not specifically refer back to childhood and is not rooted in internal instincts, but it goes with the developed personality as such and constantly arises from the objective characteristics of the social circuit of its acts. Being connected in origin not to desires but to labour, it is also an essentially practical matter in the historical materialist sense: that which gives an individual’s psychological lack of awareness its remarkable weight is the social powerlessness which characterises him as an individual in relation to social relations whose creature, however much he may try to free himself from them, he remains. And this is why such a lack of awareness is not part of a structural conception in which the eternal Oedipal triangle does not allow anyone caught up in it to escape unless they are fortunate enough to arrive at an individual cure, but of a historical perspective which urges man to collective struggle and opens onto a society rid of fetishism and the opacities of class relations, a society in which as Marx said, men’s social relations are ‘simple and intelligible, and that with regard not only to production but also to distribution’. Lack of awareness and the false consciousness which overlays it, are not the immutable destiny of and while we must certainly guard against the belief that lived consciousness could ever coincide with scientific knowledge, we would be no less mistaken in thinking that human life must be forever enclosed in ideological illusions. In The German Ideology, Marx writes:

In the present epoch, the domination of material conditions over individuals, and the suppression of individuality by chance, has assumed its sharpest and most universal form, thereby setting existing individuals a very defmite task. It has set them the task of replacing the domination of circumstances and of chance over individuals by the domination of individuals over chance and circumstances.

And he adds that within communist society, in which this inversion will be carried out, ‘the individuals’ consciousness of their mutual relations will, of course, likewise become something quite different’.He returns to this point in the Grundrisse:

The real development of the individuals from this basis (the universal development of productive forces, communications, and science) as a constant suspension of its barrier, which is recognised as a barrier, not taken for a sacred limit. Not an ideal or imagined universality of the individual, but the universality of his real and ideal relations. Hence also the grasping of his own history as a prcess, and the recognition of nature (equally present as practical power over nature) as his real body.

And it is the same theme which he takes up yet again in Capital, in connection with the fetish nature of the commodity:

The religious reflex of the real world can, in any case, only

then finally vanish, when the practical relations of everyday life offer to

man none but perfectly intelligible and reasonable relations with regard to

his fellowmen and to Nature.

The life-process of society, which is based on the process of material production,

does not strip off its mystical veil until it is treated as production by freely

associated men, and is consciously regulated by them in accordance with a settled

plan

In the last resort, transparent knowledge of oneself for oneself is not therefore psychological, individual and contemplative but social, collective and practical. And this is no doubt why, while it works no miracles, the militant revolutionary life in the very midst of capitalist society is nevertheless so often disalienating: to participate in the conscious transformation of social relations, the real human essence, is to be in the best position to penetrate the secret of their origin and consequently one’s self-origin: within the historically existing limits it to accede to freedom.