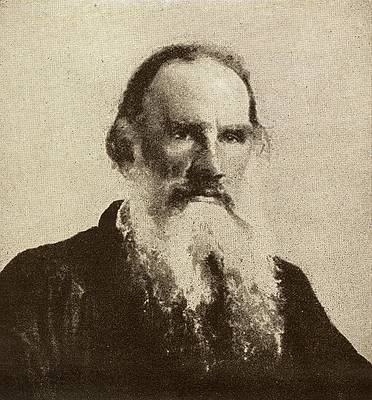

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1887

Source: Original Text from Gutenberg.org

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

At seven o'clock in the evening, dusty and weary, we entered the wide, fortified gate of Fort N——. The sun was setting, and shed oblique rosy rays over the picturesque batteries and lofty-walled gardens that surrounded the fortress, over the fields yellow for the harvest, and over the white clouds which, gathering around the snow-capped mountains, simulated their shapes, and formed a chain no less wonderful and beauteous. A young half moon, like a translucent cloud, shone above the horizon. In the native village or aul, situated near the gate, a Tatar on the roof of a hut was calling the faithful to prayer. The singers broke out with new zeal and energy.

After resting and making my toilet I set out to call upon an adjutant who was an acquaintance of mine, to ask him to make my intention known to the general. On the way from the suburb where I was quartered, I chanced to see a most unexpected spectacle in the fortress of N——. I was overtaken by a handsome two-seated vehicle in which I saw a stylish bonnet, and heard French spoken. From the open window of the commandant's house came floating the sounds of some "Lízanka" or "Kátenka" polka played upon a wretched piano, out of tune. In the tavern which I was passing were sitting a number of clerks over their glasses of wine, with cigarettes in their hands, and I overheard one saying to another,—

*

"Excuse me, but taking politics into consideration, Márya Grigór'yevna is our first lady."

A humpbacked Jew of sickly countenance, dressed in a dilapidated coat, was creeping along with a shrill, broken-down hand-organ; and over the whole suburb echoed the sounds of the finale of "Lucia."

Two women in rustling dresses, with silk kerchiefs around their necks and bright-colored sun-shades in their hands, hastened past me on the plank sidewalk. Two girls, one in pink, the other in a blue dress, with uncovered heads, were standing on the terrace of a small house, and affectedly laughing with the obvious intention of attracting the notice of some passing officers. Officers in new coats, white gloves, and glistening epaulets, were parading up and down the streets and boulevards.

I found my acquaintance on the lower floor of the general's house. I had scarcely had time to explain to him my desire, and have his assurance that it could most likely be gratified, when the handsome carriage, which I had before seen, rattled past the window where I was sitting. From the carriage descended a tall, slender man, in uniform of the infantry service and major's epaulets, and came up to the general's rooms.

"Akh! pardon me, I beg of you," said the adjutant, rising from his place: "it's absolutely necessary that I tell the general."

"Who is it that just came?" I asked.

"The countess," he replied, and donning his uniform coat hastened up-stairs.

In the course of a few minutes there appeared on the steps a short but very handsome man in a coat without epaulets, and a white cross in his button-hole.* Behind him came the major, the adjutant, and two other officers.

In his carriage, his voice, in all his motions, the general showed that he had a very keen appreciation of his high importance.

"Bon soir, Madame la Comtesse," he said, extending his hand through the carriage window.

A dainty little hand in dog-skin glove took his hand, and a pretty, smiling little visage under a yellow bonnet appeared in the window.

From the conversation which lasted several minutes, I only heard, as I went by, the general saying in French with a smile,—

"You know that I have vowed to fight the infidels; beware of becoming one!"

A laugh rang from the carriage.

"Adieu donc, cher général."

"Non, au revoir," said the general, returning to the steps of the staircase; "don't forget that I have invited myself for to-morrow evening.".

The carriage drove away.

"Here is a man," said I to myself as I went home, "who has every thing that Russians strive after,—rank, wealth, society,—and this man, before a battle the outcome of which God only knows, jests with a pretty little woman, and promises to drink tea with her on the next day, just as though he had met her at a ball!"

There at that adjutant's I became acquainted with a man who still more surprised me; it was the young lieutenant of the K. regiment, who was distinguished for his almost feminine mildness and cowardice. He came to the adjutant to pour out his peevishness and ill humor against those men who, he thought, were* intriguing against him to keep him from taking part in the matter in hand.

He declared that it was hateful to be treated so, that it was not doing as comrades ought, that he would remember him, and so forth.

As soon as I saw the expression of his face, as soon as I heard the sound of his voice, I could not escape the conviction that he was not only not putting it on, but was deeply stirred and hurt because he was not allowed to go against the Cherkess, and expose himself to their fire: he was as much hurt as a child is hurt who is unjustly punished. I could not understand it at all.