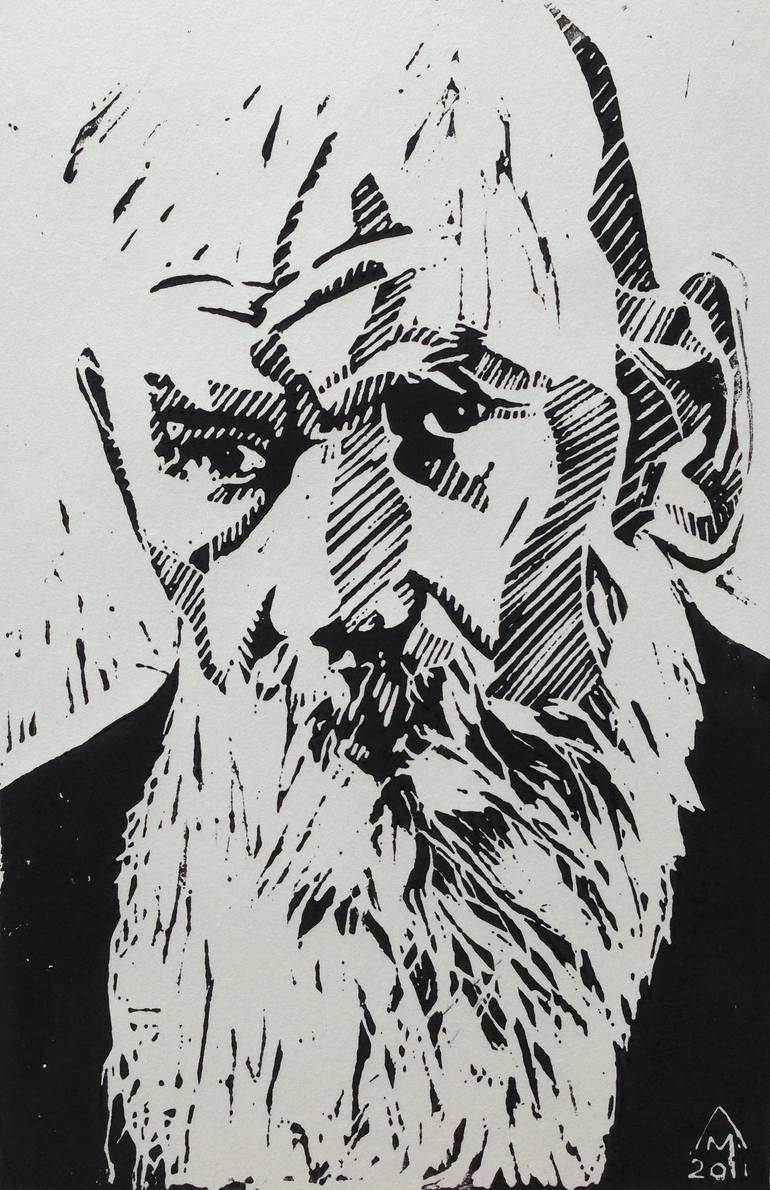

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1887

Source: Original Text from Gutenberg.org

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

At seven o'clock in the evening, having taken my tea, I started from a station, the name of which I have quite forgotten, though I remember that it was somewhere in the region of the Don Cossacks, not far from Novocherkask. It was already dark when I took my seat in the sledge next to Alyoshka, and wrapped myself in my fur coat and the robes. Back of the station-house it seemed warm and calm. Though it was not snowing, not a single star was to be seen overhead, and the sky it seemed remarkably low and black, in contrast with the clear snowy expanse stretching out before us.

We had scarcely passed by the black forms of the windmills, one of which was awkwardly waving its huge wings, and had left the station behind us, when I perceived that the road was growing rougher and more drifted; the wind began to blow more fiercely on the left, and to toss the horses' manes and tails to one side, and obstinately to lift and carry away the snow stirred up by the runners and hoofs. The little bell rang with a muffled sound; a draft of cold air forced its way through the opening in my sleeves, to my very back; and the inspector's advice came into my head,* that I had better not go farther, lest I wander all night, and freeze to death on the road.

"Won't you get us lost?" said I to the driver,[1] but, as I got no answer, I put the question more explicitly: "Say, shall we reach the station, driver? We sha'n't lose our way?"

"God knows," was his reply; but he did not turn his head. "You see what kind of going we have. No road to be seen. Great heavens!"[2]

"Be good enough to tell me, do you hope to reach the station, or not?" I insisted. "Shall we get there?"

"Must get there," said the driver; and he muttered something else, which I could not hear for the wind.

I did not wish to turn about, but the idea of wandering all night in the cold and snow over the perfectly shelterless steppe, which made up this part of the Don Cossack land, was very unpleasant. Moreover, notwithstanding the fact that I could not, by reason of the darkness, see him very well, my driver, somehow, did not please me, "nor inspire any confidence. He sat exactly in the middle, with his legs in, and not on one, side; his stature was too great; his voice expressed indolence; his cap, not like those usually worn by his class, was large and loose on all sides. Besides, he did not manage his horses in the proper way, but held the reins in both hands, just like the lackey who sat on the box behind the coachman; and, chiefly, I did not believe in him, because he had his ears wrapped up in a handkerchief. In a word, he did not please me; and it seemed as if that crooked, sinister back looming before me boded nothing good.

"In my opinion, it would be better to turn about,"* said Alyoshka to me: "fine thing it would be to be lost!"

"Great heavens! see what a snowstorm's coming! No road in sight. It blinds one's eyes. Great heavens!" repeated the driver.

We had not been gone a quarter of an hour when the driver stopped the horses, handed the reins to Alyoshka, awkwardly liberated his legs from the seat, and went to search for the road, crunching over the snow in his great boots.

"What is it? Where are you going? Are we lost?" I asked, but the driver made no reply, but, turning his face away from the wind, which cut his eyes, marched off from the sledge.

"Well, how is it?" I repeated, when he returned.

"Nothing at all," said he to me impatiently and with vexation, as though I were to blame for his missing the road; and again slowly wrapping up his big legs in the robe, he gathered the reins in his stiffened mittens.

"What's to be done?" I asked as we started off again.

"What's to be done? We shall go as God leads."

And we drove along in the same dog-trot over what was evidently an untrodden waste, sometimes sinking in deep, mealy snow, sometimes gliding over crisp, unbroken crust.

Although it was cold, the snow kept melting quickly on my collar. The low-flying snow-clouds increased, and occasionally the dry snowflakes began to fall.

It was clear that we were going out of our way, because, after keeping on for a quarter of an hour more, we saw no sign of a verst-post.

"Well, what do you think about it now?" I asked* of the driver once more. "Shall we get to the station?"

"Which one? We should go back if we let the horses have their way: they will take us. But, as for the next one, that's a problem.... Only we might perish."

"Well, then, let us go back," said I. "And indeed"—

"How is it? Shall we turn about?" repeated the driver.

"Yes, yes: turn back."

The driver shook the reins. The horses started off more rapidly; and, though I did not notice that we had turned around, the wind changed, and soon through the snow appeared the windmills. The driver's good spirits returned, and he began to be communicative.

"Lately," said he, "in just such a snowstorm some people coming from that same station lost their way. Yes: they spent the night in the hayricks, and barely managed to get here in the morning. Thanks to the hayricks, they were rescued. If it had not been for them, they would have frozen to death, it was so cold. And one froze his foot, and died three weeks afterwards."

"But now, you see, it's not cold; and it's growing less windy," I said. "Couldn't we go on?"

"It's warm enough, but it's snowing. Now going back, it seems easier. But it's snowing hard. Might go on, if you were a courier or something; but this is for your own sake. What kind of a joke would that be if a passenger froze to death? How, then, could I be answerable to your grace?"