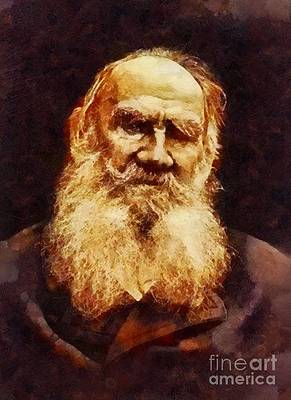

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1887

Source: Original Text from Gutenberg.org

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

The storm became more and more violent, and the snow fell dry and fine; it seemed as if we were in danger of freezing. My nose and cheeks began to tingle; more frequently the draft of cold air insinuated itself under my furs, and it became necessary to bundle up warmer. Sometimes the sledges bumped on the bare, icy crust from which the snow had been blown away. As I had already gone six hundred versts without sleeping under roof, and though I felt great interest in the outcome of our wanderings, my eyes closed in spite of me, and I drowsed. Once when I opened my eyes, I was struck, as it seemed to me at the first moment, by a bright light, gleaming over the white plain: the horizon widened considerably, the lowering black sky suddenly lifted up on all sides, the white slanting lines of the falling snow became visible, the shapes of the head troikas stood out clearly; and when I looked up, it seemed to me at the first moment that the clouds had scattered, and that only the falling snow veiled the stars. At the moment that I awoke from my drowse, the moon came out, and cast through the tenuous clouds and the falling snow her cold bright beams. I saw clearly my sledge, horses, driver, and the three troikas, plowing on in front: the first, the courier's, in which still sat on the box the one yamshchík driving at a hard trot; the second, in which rode the two drivers, who let the horses go at their own pace, and had* made a shelter out of a camel's-hair coat[7] behind which they still smoked their pipes as could be seen by the sparks glowing in their direction; and the third, in which no one was visible, for the yamshchík was comfortably sleeping in the middle. The leading driver, however, while I was napping had several times halted his horses, and attempted to find the road. Then while we stopped the howling of the wind became more audible, and the monstrous heaps of snow piling through the atmosphere seemed more tremendous. By the aid of the moonlight which made its way through the storm, I could see the driver's short figure, whip in hand, examining the snow before him, moving back and forth in the misty light, again coming back to the sledge, and springing sidewise on the seat; and then again I heard above the monotonous whistling of the wind, the comfortable, clear jingling and melody of the bells. When the head driver crept out to find the marks of the road or the hayricks, each time was heard the lively, self-confident voice of one of the yamshchíks in the second sledge shouting, "Hey, Ignashka![8] you turned off too much to the left. Strike off to the right into the storm." Or, "Why are you going round in a circle? keep straight ahead as the snow flies. Follow the snow, then you'll hit it." Or, "Take the right, take the right, old man.[9] There's something black, it must be a post." Or, "What are you getting lost for? why are you getting lost? Unhitch the piebald horse, and let him find the road for you. He'll do it every time. That would be the best way."

The man who was so free with his advice not only did not offer to unhitch his off-horse, or go himself* across the snow to hunt for the road, but did not even put his nose outside of his shelter-coat; and when Ignashka the leader, in reply to one of his proffers of advice, shouted to him to come and take the forward place since he knew the road so well, the mentor replied that when he came to drive a courier's sledge, then he would take the lead, and never once miss the road. "But our horses wouldn't go straight through a snowdrift," he shouted: "they ain't the right kind."

"Then don't you worry yourselves," replied Ignashka, gaily whistling to his horses.

The yamshchík who sat in the same sledge with the mentor said nothing at all to Ignashka, and paid no attention to the difficulty, though he was not yet asleep, as I concluded by his pipe which still glowed, and because, when we halted, I heard his measured voice in uninterrupted flow. He was telling a story. Once only, when Ignashka for the sixth or seventh time came to a stop, it seemed to vex him because his comfort in traveling was disturbed, and he shouted,—

"Stopping again? He's missing the road on purpose. Call this a snowstorm! The surveyor himself could not find the road! he would let the horses find it. We shall freeze to death here; just let him go on regardless!"

"What! Don't you know a poshtellion froze to death last winter?" shouted my driver.

All this time the driver of the third troïka had not been heard from. But once while we were stopping, the mentor shouted, "Filipp! ha! Filipp!" and not getting any response remarked,—

"Can he have frozen to death? Ignashka, you go and look."

*

Ignashka, who was responsible for all, went to his sledge, and began to shake the sleeper.

"See what drink has done for him! Tell us if you are frozen to death!" said he, shaking him.

The sleeper grunted a little, and then began to scold.

"Live enough, fellows!" said Ignashka, and again started ahead, and once more we drove on; and with such rapidity that the little brown off-horse, in my three-span, which was constantly whipping himself with his tail, did not once interrupt his awkward gallop.