Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1887

Source: Original Text from Gutenberg.org

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

"Is our lady asleep, or not?" asked a muzhík's hoarse voice suddenly near Aksiutka. She opened her eyes, which had been tightly shut, and saw a form which it seemed to her was higher than the wing. She wheeled round, and sped back so fast that her petticoat did not have time to catch up with her. With one bound she was on the steps, with another in the sitting-room, and giving a wild shriek flung herself on the lounge.

Duniasha, her aunt, and the second girl almost died of fright; but they had no time to open their eyes, ere heavy, deliberate, and irresolute steps were heard in the entry and at the door. Duniasha ran into her mistress's room, dropping the cerate. The second girl hid behind a skirt that was hanging on the wall. The aunt, who had more resolution, was about to hold the door; but the door opened, and a muzhík strode into the room.

It was Dutlof in his huge boots. Not paying any heed to the affrighted women, his eyes sought the icons; and, not finding the small holy image that hung in a corner, he crossed himself toward the cupboard, laid his cap down on the window, and thrusting his thick hand into his sheepskin coat, as though he were trying to scratch himself under the arm, he drew out a letter with five brown seals, imprinted with an anchor. Duniasha's aunt put her hand to her breast; she was scarcely able to articulate,—

*

"How you frightened me, Naumuitch![23] I ca-n-n't sa-y a wo-r-d. I thought that the end ... had ... come."

"What do you want?" asked the second girl, emerging from behind the skirt.

"And they have stirred up our lady so," said Duniasha coming from the other room. "What made you come up to the sitting-room without knocking? You stupid muzhík!"

Dutlof, without making any excuse, said that he must see the mistress.

"She is ill," said Duniasha.

By this time Aksiutka was snorting with such unbecomingly loud laughter, that she was again obliged to hide her head under the pillows, from which, for a whole hour, notwithstanding Duniasha's and her aunt's threats, she was unable to lift it without falling into renewed fits of laughter, as though something were loose in her rosy bosom and red cheeks. It seemed to her so ridiculous that they were all so frightened—and she again would hide her head, and, as it were in convulsions, shuffle her shoes, and shake with her whole body.

Dutlof straightened himself up, looked at her attentively as though wishing to account for this peculiar manifestation; but, not finding any solution, he turned away and continued to explain his errand.

"Of course, as this is a very important business," he said, "just tell her that a muzhík has brought her the letter with the money."

"What money?"

*

Duniasha, before referring the matter to the mistress, read the address, and asked Dutlof when and how he had got this money which Ilyitch should have brought back from the city. Having learned all the particulars, and sent the errand-girl, who still continued to laugh, out into the entry, Duniasha went to the mistress; but to Dutlof's surprise the lady would not receive him at all, and sent no message to him through Duniasha.

"I know nothing about it, and wish to know nothing," said the mistress, "about any muzhík or any money. I can not and I will not see any one. Let him leave me in peace."

"But what shall I do?" asked Dutlof, turning the envelope around and around; "it's no small amount of money. It's written on there, isn't it?" he inquired of Duniasha, who again read to him the superscription.

It seemed hard for Dutlof to believe Duniasha. He seemed to hope that the money did not belong to the gracious lady, and that the address read otherwise. But Duniasha repeated it a second time. He sighed, placed the envelope in his breast, and prepared to go out.

"I must give it to the police inspector," he said.

"Simpleton, I will ask her again; I will tell her," said Duniasha, detaining him when she saw the envelope disappearing under his coat. "Give me the letter."

Dutlof took it out again, but did not immediately put it into Duniasha's outstretched hand.

"Tell her that Dutlof Sem'yón found it on the road."

"Well, give it here."

*

"I was thinking—well, take it. A soldier read the address for me—that it had money."

"Well, let me have it."

"I didn't dare to go home on account of this," said Dutlof again, not letting go the precious envelope. "Well, let her see it."

Duniasha took the envelope, and once more went to her ladyship.

"Duniasha,"[24] said the mistress in a reproachful tone, "don't speak to me about that money. I can't think of any thing else except that poor little babe."

"The muzhík, my lady,[25] knows not who you want him to give it to," insisted Duniasha.

The lady broke the seals, shuddered as soon as she saw the money, and pondered for a moment.

"Horrible money! it has brought nothing but woe," she mused.

"It is Dutlof, my lady. Do you wish him to go, or will you come and see him? Is all the money there?" asked Duniasha.

"I do not wish this money. This is horrible money. What harm it has done! Tell him that he may have it if he wants it," suddenly exclaimed the lady, seizing Duniasha's hand.

"Fifteen hundred rubles," remarked Duniasha, smiling gently as to a child.

"Let him have it all," repeated the lady impatiently. "Why, don't you understand me? This is misfortune's money: don't ever speak about it to me again. Let this muzhík have it, if he brought it. Go, go right away!"

Duniasha returned into the sitting-room.

"Was it all there?" asked Dutlof.

*

"Count for yourself," said Duniasha, handing him the envelope: "she told me to give it to you."

Dutlof stuffed his cap under his arm, and bending over tried to count.

"Haven't you got a counting-machine?"

Dutlof understood that it was a whim of the mistress's not to count, and that she had bidden him to do it.

"Take it home, and count it. It's yours,—your money," said Duniasha severely. "Says she, 'I don't want it; let the man have it who found it.'"

Dutlof, not straightening himself up, fixed his eyes on Duniasha.

Duniasha's aunt also clapped her hands. "Goodness gracious![26] God has given you such luck! Goodness gracious!"

The second girl could not believe it. "You're joking! Did really Avdót'ya Nikolóvna say that?"

"What do you mean—joking! She told me to give it to the muzhík. Now take your money, and be off," said Duniasha, not hiding her vexation. "One has sorrow, another joy."

"It must be a joke,—fifteen hundred rubles!" said the aunt.

"More than that," said Duniasha sharply. "Now you will place a great big candle for Mikola,"[27] she continued maliciously. "What! have you lost your wits? It would be good for some poor fellow. And you have so much of your own."

Dutlof finally arrived at a comprehension that it was meant in earnest; and he began to fold together and smooth down the envelope with the money, which in the counting he had burst open: but his hands trembled, and he kept looking at the women, to persuade* himself that it was not a jest.

"You see you haven't come to your senses with joy," said Duniasha, making it evident that she despised both the muzhík and money. "Give it to me, I'll fix it for you."

And she offered to take it, but Dutlof did not trust it in her hands. He doubled the money up, thrust it in still farther, and took his cap.

"Glad?"

"I don't know; what's to be said? Here it's"—He did not finish his sentence, but waved his hand, grinned, almost burst into tears, and went out.

The bell tinkled in the mistress's room.

"Well, did you give it to him?"

"I did."

"Well, was he very glad?"

"He was like one gone crazy."

"Oh, bring him back! I want to ask him how he found it. Bring him in here. I can't go out to him."

Duniasha flew out, and overtook the muzhík in the hall. He had not put on his hat, but had taken out his purse, and bending over was opening it; but the money he held between his teeth. Maybe it seemed to him that it was not his until he had put it in his purse. When Duniasha called him back, he was startled.

"What ... Avdót'ya?... Avdót'ya Mikolavna? Is she going to take it away from me? If you would only take my part, I would bring you some honey,—before God I would."

"All right, bring it,'"

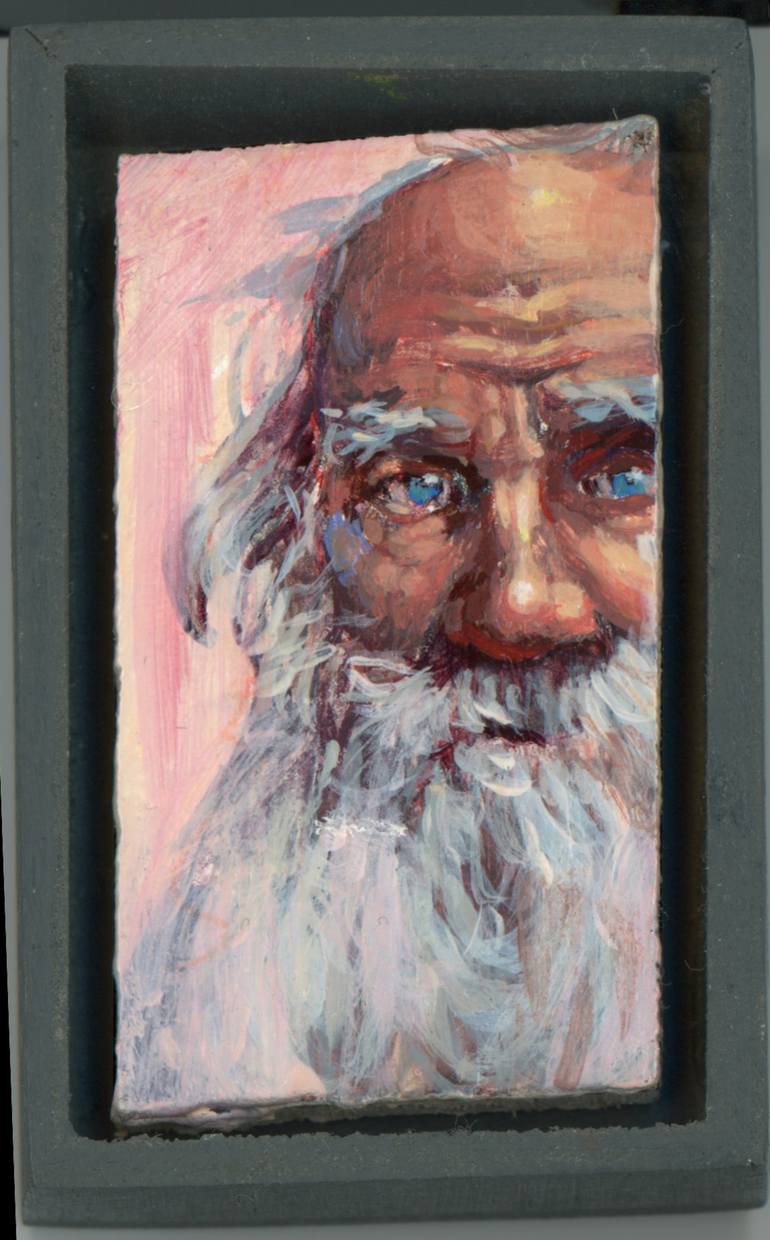

Again the door opened, and the muzhík was led into the mistress's presence. It was not a happy moment for him. "Akh! she's going to take it back!" he said to himself, as he went through the rooms, * lifting his feet very high, as though walking through tall grass, so as not to make a noise with his big wooden shoes. He did not comprehend, and he scarcely noticed what was around him. He passed by the mirror; he saw some flowers, some muzhík or other lifting up his feet shod in sabots, the bárin painted with one eye and something that seemed to him like a green tub, and a white object.... Suddenly, from the white object issued a voice. It was the mistress. He could not distinguish any one clearly, but he rolled his eyes around. He knew not where he was, and every thing seemed to be in a mist.

"Is it you, Dutlof?"

"It's me, your ladyship.[28] It's just as it was. I didn't touch it," he said. "I wasn't glad,—before God, I wasn't. I almost killed my horse."

"It's your good luck," she said with a perfectly sweet smile. "Keep it, keep it. It's yours."

He only opened wide his eyes.

"I am glad that you have it. God grant that it prove useful to you. Are you glad to have it?"

"How could I help being glad? Glad as I can be, mátushka! I will always pray to God for you. I am as glad as I can be, that, glory to God, our mistress is alive. Only it was my fault."

"How did you find it?"

"You know that we can always work for our lady for honor's sake, and, if not that" ...

"He's getting all mixed up, my lady said," Duniasha.

"I carried my nephew, who's gone as a necruit, and on my way back I found it on the road. Polikéï must have dropped it accidentally."

*

"Well, now go, now go! I am glad."

"So am I glad, mátushka," said the muzhík.

Then he recollected that he had not thanked her, but he did not know how to go about it in the proper manner. The lady and Duniasha both smiled, as he again started to walk, as though through tall grass, and by main force conquered his impulse to break into a run. But all the time it seemed to him that they were going to hold him, and take it from him.