Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1899

Source: Anna Karenina, by Leo Tolstoy, translated from Russian to English by Constance Clara Garnett

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

Whether it was because there were fewer peasants present, or because he was not occupied with himself, but with the matter in hand, Nekhludoff felt no agitation when the seven peasants chosen from the villagers responded to the summons.

He first of all expressed his views on private ownership of land.

"As I look upon it," he said, "land ought not to be the subject of purchase and sale, for if land can be sold, then those who have money will buy it all in and charge the landless what they please for the use of it. People will then be compelled to pay for the right to stand on the earth," he added, quoting Spencer's argument.

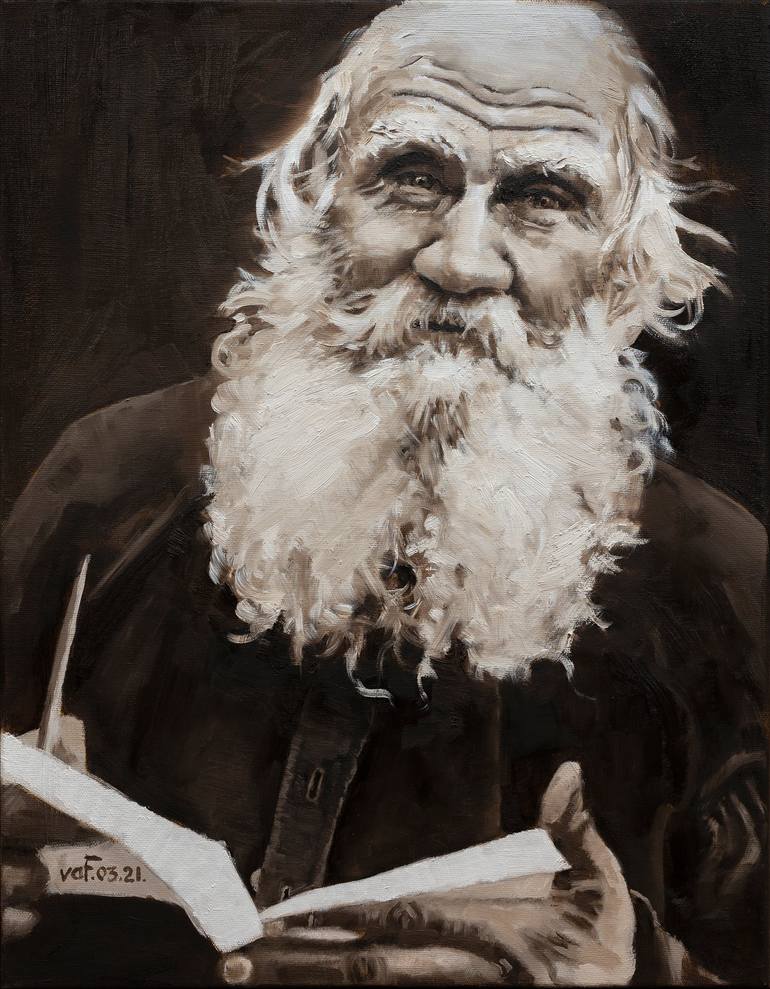

"There remains to put on wings and fly," said an old man with smiling eyes and gray beard.

"That's so," said a long-nosed peasant in a deep basso.

"Yes, sir," said the ex-soldier.

"The old woman took some grass for the cow. They caught her, and to jail she went," said a good-natured, lame peasant.

"There is land for five miles around, but the rent is higher than the land can produce," said the toothless, angry old man.

"I am of the same opinion as you," said Nekhludoff, "and that is the reason I want to give you the land."

"Well, that would be a kind deed," said a broad-shouldered old peasant with a curly, grayish beard like that of Michael Angelo's Moses, evidently thinking that Nekhludoff intended to rent out the land.

"That is why I came here. I do not wish to own the land any longer, but it is necessary to consider how to dispose of it."

"You give it to the peasants—that's all," said the toothless, angry peasant.

For a moment Nekhludoff was confused, seeing in these words doubt of the sincerity of his purpose. But he shook it off, and took advantage of the remark to say what he intended.

"I would be only too glad to give it," he said, "but to whom and how shall I give it? Why should I give it to your community rather than to the Deminsky community?" Deminsky was a neighboring village with very little land.

They were all silent. Only the ex-soldier said, "Yes, sir."

"And now tell me how would you distribute the land?"

"How? We would give each an equal share," said an oven-builder, rapidly raising and lowering his eyebrows.

"How else? Of course divide it equally," said a good-natured, lame peasant, whose feet, instead of socks, were wound in a white strip of linen.

This decision was acquiesced in by all as being satisfactory.

"But how?" asked Nekhludoff, "are the domestics also to receive equal shares?"

"No, sir," said the ex-soldier, assuming a cheerful mood. But the sober-minded tall peasant disagreed with him.

"If it is to be divided, everybody is to get an equal share," after considering awhile, he said in a deep basso.

"That is impossible," said Nekhludoff, who was already prepared with his objection. "If everyone was to get an equal share, then those who do not themselves work would sell their shares to the rich. Thus the land would again get into the hands of the rich. Again, the people that worked their own shares would multiply, and the landlords would again get the landless into their power."

"Yes, sir," the ex-soldier hastily assented.

"The selling of land should be prohibited; only those that cultivate it themselves should be allowed to own it," said the oven-builder, angrily interrupting the soldier.

To this Nekhludoff answered that it would be difficult to determine whether one cultivated the land for himself or for others.

Then the sober-minded old man suggested that the land should be given to them as an association, and that only those that took part in cultivating it should get their share.

Nekhludoff was ready with arguments against this communistic scheme, and he retorted that in such case it would be necessary that all should have plows, that each should have the same number of horses, and that none should lag behind, or that everything should belong to society, for which the consent of every one was necessary.

"Our people will never agree," said the angry old man.

"There will be incessant fighting among them," said the white-bearded peasant with the shining eyes. "The women will scratch each other's eyes out."

"The next important question is," said Nekhludoff, "how to divide the land according to quality. You cannot give black soil to some and clay and sand to others."

"Let each have a part of both," said the oven-builder.

To this Nekhludoff answered that it was not a question of dividing the land in one community, but of the division of land generally among all the communities. If the land is to be given gratis to the peasants, then why should some get good land, and others poor land? There would be a rush for the good land.

"Yes, sir," said the ex-soldier.

The others were silent.

"You see, it is not as simple as it appears at first sight," said Nekhludoff. "We are not the only ones, there are other people thinking of the same thing. And now, there is an American, named George, who devised the following scheme, and I agree with him."

"What is that to you? You are the master; you distribute the land, and there is an end to it," said the angry peasant.

This interruption somewhat confused Nekhludoff, but he was glad to see that others were also dissatisfied with this interruption.

"Hold on, Uncle Semen; let him finish," said the old man in an impressive basso.

This encouraged Nekhludoff, and he proceeded to explain the single-tax theory of Henry George.

"The land belongs to no one—it belongs to the Creator."

"That's so!"

"Yes, sir."

"The land belongs to all in common. Every one has an equal right to it. But there is good land, and there is poor land. And the question is, how to divide the land equally. The answer to this is, that those who own the better land should pay to those who own the poorer the value of the better land. But as it is difficult to determine how much anyone should pay, and to whom, and as society needs money for common utilities, let every land owner pay to society the full value of his land—less, if it is poorer; more, if it is better. And those who do not wish to own land will have their taxes paid by the land owners."

"That's correct," said the oven-builder. "Let the owner of the better land pay more."

"What a head that Jhorga had on him!" said the portly old peasant with the curls.

"If only the payments were reasonable," said the tall peasant, evidently understanding what it was leading to.

"The payments should be such that it would be neither too cheap nor too dear. If too dear, it would be unprofitable; if too cheap, people would begin to deal in land. This is the arrangement I would like you to make."

Voices of approval showed that the peasants understood him perfectly.

"What a head!" repeated the broad-shouldered peasant with the curls, meaning "Jhorga."

"And what if I should choose to take land?" said the clerk, smiling.

"If there is an unoccupied section, take and cultivate it," said Nekhludoff.

"What do you want land for? You are not hungering without land," said the old man with the smiling eyes.

Here the conference ended.

Nekhludoff repeated his offer, telling the peasants to consult the wish of the community, before giving their answer.

The peasants said that they would do so, took leave of Nekhludoff and departed in a state of excitement. For a long time their loud voices were heard, and finally died away about midnight.

The peasants did not work the following day, but discussed their master's proposition. The community was divided into two factions. One declared the proposition profitable and safe; the other saw in the proposition a plot which it feared the more because it could not understand it. On the third day, however, the proposition was accepted, the fears of the peasants having been allayed by an old woman who explained the master's action by the suggestion that he began to think of saving his soul. This explanation was confirmed by the large amount of money Nekhludoff had distributed while he remained in Panov. These money gifts were called forth by the fact that here, for the first time, he learned to what poverty the peasants had been reduced and though he knew that it was unwise, he could not help distributing such money as he had, which was considerable.

As soon as it became known that the master was distributing money, large crowds of people from the entire surrounding country came to him asking to be helped. He had no means of determining the respective needs of the individuals, and yet he could not help giving these evidently poor people money. Again, to distribute money indiscriminately was absurd. His only way out of the difficulty was to depart, which he hastened to do.

On the third day of his visit to Panov, Nekhludoff, while looking over the things in the house, in one of the drawers of his aunt's chiffonnier, found a picture representing a group of Sophia Ivanovna, Catherine Ivanovna, himself, as student, and Katiousha—neat, fresh, beautiful and full of life. Of all the things in the house Nekhludoff removed this picture and the letters. The rest he sold to the miller for a tenth part of its value.

Recalling now the feeling of pity over the loss of his property which he had experienced in Kusminskoie, Nekhludoff wondered how he could have done so. Now he experienced the gladness of release and the feeling of novelty akin to that experienced by an explorer who discovers new lands.