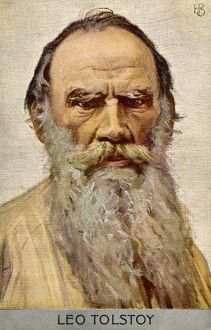

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1904

Source: Original Text from Gutenberg.org

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

I began again to analyze the matter from a third and purely personal point of view. Among the phenomena which particularly impressed me during my benevolent activity, there was one,—a very strange one,—which I could not understand for a long time.

Whenever I happened, in the street or at home, to give a poor person a trifling sum without entering into conversation with him, I saw on his face, or imagined I saw, an expression of pleasure and gratitude, and I myself experienced an agreeable feeling at this form of charity. I saw that I had done what was expected of me. But when I stopped and began to question the man about his past and present life, entering more or less into particulars, I felt it was impossible to give him 3 or 20 kopecks; and I always began to finger the money in my purse, and, not knowing how much to give, I always gave more under these circumstances; but, nevertheless, I saw that the poor man went away from me dissatisfied. When I entered into still closer intercourse with him, my doubts as to how much I should give increased; and, no matter what I gave, the recipient seemed more and more gloomy and dissatisfied.

As a general rule, it always happens that if, upon nearer acquaintance with the poor man I gave him three rubles or even more, I always saw gloominess, dissatisfaction, even anger depicted on his face; and sometimes, after having received from me ten rubles, he has left me without even thanking me, as if I had offended him.

In such cases I was always uncomfortable and ashamed, and felt myself guilty. When I watched the poor person during weeks, months, or years, helped him, expressed my views, and became intimate with him, then our intercourse became a torment, and I saw that the man despised me. And I felt that he was right in doing so. When in the street a beggar asks me, along with other passersby, for three kopecks, and I give it him, then, in his estimation, I am a kind and good man who gives “one of the threads which go to make the shirt of a naked one”: he expects nothing more than a thread, and, if I give it, he sincerely blesses me.

But if I stop and speak to him as man to man, show him that I wish to be more than a mere passerby, and, if, as it often happened, he shed tears in relating his misfortune, then he sees in me not merely a chance helper, but that which I wish him to see,—a kind man. If I am a kind man, my kindness cannot stop at twenty kopecks, or at ten rubles, or ten thousand. One cannot be a slightly kind man. Let us suppose that I give him much; that I put him straight, dress him, and set him on his legs so that he can help himself; but, from some reason or other, either from an accident or his own weakness, he again loses the great-coat and clothing and money I gave him, he is again hungry and cold, and he again comes to me, why should I refuse him assistance? For if the cause of my benevolent activity was merely the attainment of some definite, material object, such as giving him so many rubles or a certain great-coat, then, having given them I could be easy in my mind; but the cause of my activity was not this: the cause of it was my desire to be a kind man—i.e., to see myself in everybody else. Everyone understands kindness in this way, and not otherwise.

Therefore if such a man should spend in drink all you gave him twenty times over, and be again hungry and cold, then, if you are a benevolent man, you cannot help giving him more money, you can never leave off doing so while you have more than he has; but if you draw back, you show that all you did before was done not because you are benevolent, but because you wish to appear so to others and to him. And it was because I had to back out of such cases, and to cease to give, and thus to disown the good, that I felt a painful sense of shame.

What was this feeling, then?

I had experienced it in Liapin's house and in the country, and when I happened to give money or anything else to the poor, and in my adventures among the town people. One case which occurred lately reminded me of it forcibly, and led me to discover its cause.

It happened in the country. I wanted twenty kopecks to give to a pilgrim. I sent my son to borrow it from somebody. He brought it to the man, and told me that he had borrowed it from the cook. Some days after, other pilgrims came, and I was again in need of twenty kopecks. I had a ruble. I recollected what I owed the cook, went into the kitchen, hoping that he would have some more coppers. I said,—

“I owe you twenty kopecks: here is a ruble.”

I had not yet done speaking when the cook called to his wife from the adjoining room: “Parasha, take it,” he said.

Thinking she had understood what I wanted, I gave her the ruble. I must tell you that the cook had been living at our house about a week, and I had seen his wife, but had never spoken to her. I merely wished to tell her to give me the change, when she briskly bowed herself over my hand and was about to kiss it, evidently thinking I was giving her the ruble. I stammered out something and left the kitchen. I felt ashamed, painfully ashamed, as I had not felt for a long time. I actually trembled, and felt that I was making a wry face; and, groaning with shame, I ran away from the kitchen.

This feeling, which I fancied I had not deserved, and which came over me quite unexpectedly, impressed me particularly, because it was so long since I had felt anything like it and also because I fancied that I, an old man, had been living in a way I had no reason to be ashamed of.

This surprised me greatly. I related the case to my family, to my acquaintances, and they all agreed that they also would have felt the same. And I began to reflect: Why is it that I felt so?

The answer came from a case which had formerly occurred to me in Moscow. I reflected upon this case, and I understood the shame which I felt concerning the incident with the cook's wife, and all the sensations of shame I had experienced during my charitable activity in Moscow, and which I always feel when I happen to give anything beyond trifling alms to beggars and pilgrims, which I am accustomed to give, and which I consider not as charity, but as politeness and good breeding. If a man asks you for a light, you must light a match if you have it. If a man begs for three or twenty kopecks, or a few rubles, you must give if you have them. It is a question of politeness, not of charity.

The following is the case I referred to. I have already spoken about the two peasants with whom I sawed wood three years ago. One Saturday evening, in the twilight, I was walking with them back to town. They were going to their master to receive their wages. On crossing the Dragomilor bridge we met an old man. He begged, and I gave him twenty kopecks. I gave, thinking what a good impression my alms would make upon Simon, with whom I had been speaking on religious questions.

Simon, the peasant from Vladímir, who had a wife and two children in Moscow, also stopped, turned up the lappet of his caftan, and took out his purse; and, after having looked over his money, he picked out a three-kopeck piece, gave it to the old man, and asked for two kopecks back. The old man showed him in his hand two three-kopeck pieces and a single kopeck. Simon looked at it, was about to take one kopeck, but, changing his mind, took off his cap, crossed himself, and went away, leaving the old man the three-kopeck piece.

I was acquainted with all Simon's pecuniary circumstances. He had neither house nor other property. When he gave the old man the three kopecks, he possessed six rubles and fifty kopecks, which he had been saving up, and this was all the capital he had.

My property amounted to about six hundred thousand rubles. I had a wife and children, so also had Simon. He was younger than I, and had not so many children; but his children were young, and two of mine were grown-up men, old enough to work, so that our circumstances, independently of our property, were alike, though even in this respect I was better off than he.

He gave three kopecks, I gave twenty. What was, then, the difference in our gifts? What should I have given in order to do as he had done? He had six hundred kopecks; out of these he gave one, and then another two. I had six hundred thousand rubles. In order to give as much as Simon gave, I ought to have given three thousand rubles, and asked the man to give me back two thousand; and, in the event of his not having change, to leave him these two also, cross myself, and go away calmly, conversing about how people live in the manufactories, and what is the price of liver in the Smolensk market.

I thought about it at the time, but it was long before I was able to draw from this case the conclusion which inevitably follows from it. This conclusion appears to be so uncommon and strange, notwithstanding its mathematical accuracy, that it requires time to get accustomed to it. One is inclined to think there is some mistake, but there is none. It is only the terrible darkness of prejudice in which we live.

This conclusion, when I arrived at it and recognized its inevitableness, explained to me the nature of my feelings of shame in the presence of the cook's wife, and before all the poor to whom I gave and still give money. Indeed, what is that money which I give to the poor, and which the cook's wife thought I was giving her? In the majority of cases it forms such a minute part of my income that it cannot be expressed in a fraction comprehensible to Simon or to a cook's wife,—it is in most cases a millionth part or thereabout. I give so little that my gift is not, and cannot be, a sacrifice to me: it is only a something with which I amuse myself when and how it pleases me. And this was indeed how my cook's wife had understood me. If I gave a stranger in the street a ruble or twenty kopecks, why should I not give her also a ruble? To her, such a distribution of money is the same thing as a gentleman throwing gingerbread nuts into a crowd. It is the amusement of people who possess much “fool's money.” I was ashamed, because the mistake of the cook's wife showed me plainly what ideas she and all poor people must have of me. “He is throwing away ‘fool's money’”; that is, money not earned by him.

And, indeed, what is my money, and how did I come by it? One part of it I collected in the shape of rent for my land, which I had inherited from my father. The peasant sold his last sheep or cow in order to pay it.

Another part of my money I received from the books I had written. If my books are harmful, and yet sell, they can only do so by some seductive attraction, and the money which I receive for them is badly earned money; but if my books are useful, the thing is still worse. I do not give them to people, but say, “Give me so many rubles, and I will sell them to you.”

As in the former case a peasant sells his last sheep, here a poor student or a teacher does it: each poor person who buys denies himself some necessary thing in order to give me this money. And now that I have gathered much of such money what am I to do with it? I take it to town, give it to the poor only when they satisfy all my fancies and come to town to clean pavements, lamps, or boots, to work for me in the factories, and so on. And with this money I draw from them all I can. I try to give them as little as I can and take from them as much as possible.

Now, quite unexpectedly, I begin to share all this said money with these same poor persons for nothing; but not with everyone, only as fancy prompts me. And why should not every poor man expect that his turn might come to-day to be one of those with whom I amuse myself by giving them my “fool's money”?

So everyone regards me as the cook's wife did. And I had gone about with the notion that this was charity,—this taking away thousands with one hand, and with the other throwing kopecks to those I select!

No wonder I was ashamed. But before I can begin to do good I must leave off the evil and put myself in a position in which I should cease to cause it. But all my course of life is evil. If I were to give away a hundred thousand, I should not yet have put myself in a condition in which I could do good, because I have still five hundred thousand left.

It is only when I possess nothing at all that I shall be able to do a little good; such as, for instance, the poor prostitute did who nursed a sick woman and her child for three days. Yet this seemed to me to be but so little! And I ventured to think of doing good! One thing only was true, which I at first felt on seeing the hungry and cold people outside Liapin's house,—that I was guilty of that; and that to live as I did was impossible, utterly impossible. What shall we do then? If somebody still needs an answer to this question, I will, by God's permission, give one, in detail.