Go

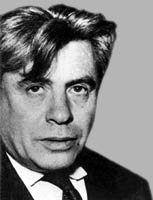

Gödel, Kurt (1906-1978)

Austrian-born mathematician, logician, and author of Gödel's theorem, which states that within any consistent mathematical system there are propositions that cannot be proved or disproved on the basis of the axioms within that system and that, therefore, it is uncertain that the basic axioms of arithmetic will not give rise to contradictions. Gödel’s theorem applied Hilbert’s formalist mathematical method, and put a final end to the Logicism of Bertrand Russell and Gottlob Frege; his approach contributed to the algorithmic methods of Alan Turing, the founder of modern computer science. He was an advocate of Kant’s epistemology, and many people see Gödel’s theorem as important in proving the essentially open-ended nature of knowledge.

Austrian-born mathematician, logician, and author of Gödel's theorem, which states that within any consistent mathematical system there are propositions that cannot be proved or disproved on the basis of the axioms within that system and that, therefore, it is uncertain that the basic axioms of arithmetic will not give rise to contradictions. Gödel’s theorem applied Hilbert’s formalist mathematical method, and put a final end to the Logicism of Bertrand Russell and Gottlob Frege; his approach contributed to the algorithmic methods of Alan Turing, the founder of modern computer science. He was an advocate of Kant’s epistemology, and many people see Gödel’s theorem as important in proving the essentially open-ended nature of knowledge.

A member of the faculty of the University of Vienna from 1930, Gödel was also a member of the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton; he emigrated to the United States in 1940 and from 1953 served as a professor at the institute.

Gödel's proof first appeared in an article in the Monatshäfte für Mathematik und Physik, vol. 38 (1931), On formally indeterminable propositions of the Principia Mathematica of Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell. This article ended nearly a century of attempts to establish axioms that would provide a rigorous basis for all mathematics.

Further Reading: The Development of the Foundations of Mathematics in the Light of Philosophy. See also, Ernst Kolman and Sonya Yanovskaya's Hegel & Mathematics and Value & Quantity.

Goldman, Emma (1869 - 1940)

American anarchist, lecturer and writer in the United States and later a participant in the Spanish Civil War.

American anarchist, lecturer and writer in the United States and later a participant in the Spanish Civil War.

Born in Lithuania, her family owners of a small hotel, Goldman spent her early years in in Königsberg, East Prussia and later (in 1882) moved to St. Petersburg. As semi-wealthy Jews, Goldman and her family at times suffered from social and political persecution. By the time she was 16 (1885), in conflict with her father who tried to marry her off, she emigrated with her half-sister to the United States (Rochester, New York), where she began working in clothing factories. At 19, she was married for ten months, when she divorced her husband. Her two volume, 56 chapter autobiography Living My Life , begins three years after her arrival in the United States:

IT WAS THE 15TH OF AUGUST 1889, THE DAY OF MY ARRIVAL IN New York City. I was twenty years old. All that had happened in my life until that time was now left behind me, cast off like a worn-out garment. A new world was before me, strange and terrifying. But I had youth, good health, and a passionate ideal. Whatever the new held in store for me I was determined to meet unflinchingly.

After her move, she became close to Alexander Berkman, who together (in 1892) attempted to assassinate Henry Clay Frick, during the homestead steel strike. To raise money for buying the gun, Goldman unsuccessfully tried to prostitute herself. Their attempt of assassination was a failure, Frick was slightly injured, and workers were not at all incited to revolt. Berkman was sentenced to 22 years in prison, while Goldman attempted to defend Berkman with a passionately moral argument; her own involvement in the assassination was not tried.

By 1893, however, Goldman was imprisoned for her first time, after attempting to incite striking workers to revolt. Goldman was again imprisoned after distributing birth control literature. In 1906, Berkman was freed early from his prison term, and together they began again political education – founding Mother Earth, a periodical Goldman edited until it was forcibly suppressed by the U.S. government in 1917. In 1908 her naturalization as a U.S. citizen was revoked. Goldmann nevertheless stayed in the U.S., and continued to publicly speak on anarchism and also on the current European drama of Henrik Ibsen, August Strindberg, George Bernard Shaw, and others.

In 1917, Goldman was imprisoned again (for two years) for setting up "No Conscription" leagues and speaking out against the US involvement in the war. In 1919, along with Berkman and 247 others, she was forcibly deported from United States to Soviet Russia as a subversive.

Here Goldman saw Russia for the first time under Soviet rule and strongly disapproved. She was horrified by the terrible living conditions in Russia and the repressive Soviet government. In the beginning she strongly spoke out against the government for its repressive measures against those who were attacking it during the Civil War. After the end of the (Western) Civil War, the nation in ruins by the destruction, Goldman chastised the government for the poor living conditions. When the Soviet government began encouraging the opposition parties, once brutally repressed, to help rebuild the nation, Goldman was outraged, believing that this was the ultimate compromise of revolutionary principles – to allow these "bourgeois" into the government. A few other anarchists joined Goldman in voicing extreme opposition to this, and attempted to start another Civil War. The first and last result of these attempts happened at Kronstadt, where mutinying soldiers attempted to lead a Civil War against the Soviet government. After this was brutally crushed by the Soviet government, Goldman, to disillusioned to continue to be revolutionary, left Soviet Russia for Western Europe.

In the last 20 years of her life she remained active through lecturing and writing. She later joined the antifascist cause in Spain during its Civil War and died working on its behalf.

See: Emma Goldman Reference Archive

Goldman, Lucien (1913-1970)

Renowned sociologist, socialist humanist, born in 1913 in Botosani, Romania, and studiedin Vienna under Max Adler, studied Law at Bucharest and Paris, and philosophy at Vienna, Zurich and Paris, and subsequently worked with Jean Piaget in Geneva. At the Sorbonne, he was director of studies at the École Pratique de Hautes Études, Paris, and directed the Center for Studies of Literature at the Université Libre de Bruxelles and Solvay Institute. Died in Paris in 1970.

Renowned sociologist, socialist humanist, born in 1913 in Botosani, Romania, and studiedin Vienna under Max Adler, studied Law at Bucharest and Paris, and philosophy at Vienna, Zurich and Paris, and subsequently worked with Jean Piaget in Geneva. At the Sorbonne, he was director of studies at the École Pratique de Hautes Études, Paris, and directed the Center for Studies of Literature at the Université Libre de Bruxelles and Solvay Institute. Died in Paris in 1970.

Goldman's major works are Human Community and the Universe according to Kant, Human Sciences and Philosophy, The Hidden God, Dialectical Research and Three Studies on the Sociology of the Novel.

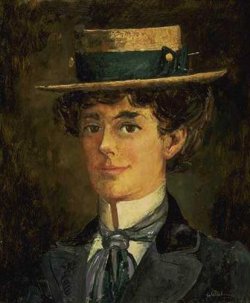

Goldstein, Vida (1869-1949)

Australian Feminist and Suffragist, born Portland, Victoria, 1869, died 15 August 1949. One of five children. Educated at Presbyterian Ladies College. Goldstein was the president of the feminist Women’s Federal Political Association, and also edited Women’s Sphere (1900-1908). She stood as an Independent Woman Candidate for the Senate in 1910, and for the House of Representatives in 1913 and 1914. Although she was not elected, this made her the first woman to nominate for Australian Parliament. She helped found the National Council of Women, and was the Delegate from Australia and New Zealand to the International Woman Suffrage Conference, Washington D. C. in 1902. She was chairperson of the Australian Peace Alliance in 1914 and led its radical wing into the new Women’s Peace Army, which she helped found in 1915. She was owner-editor, by turn, of Women’s Sphere and the Woman Voter. Throughout her life Goldstein campaigned on many social issues including women’s franchise, the Queen Victoria women’s hospital, peace, birth control and naturalisation laws.

Australian Feminist and Suffragist, born Portland, Victoria, 1869, died 15 August 1949. One of five children. Educated at Presbyterian Ladies College. Goldstein was the president of the feminist Women’s Federal Political Association, and also edited Women’s Sphere (1900-1908). She stood as an Independent Woman Candidate for the Senate in 1910, and for the House of Representatives in 1913 and 1914. Although she was not elected, this made her the first woman to nominate for Australian Parliament. She helped found the National Council of Women, and was the Delegate from Australia and New Zealand to the International Woman Suffrage Conference, Washington D. C. in 1902. She was chairperson of the Australian Peace Alliance in 1914 and led its radical wing into the new Women’s Peace Army, which she helped found in 1915. She was owner-editor, by turn, of Women’s Sphere and the Woman Voter. Throughout her life Goldstein campaigned on many social issues including women’s franchise, the Queen Victoria women’s hospital, peace, birth control and naturalisation laws.

See Australian Woman Movement Archive.

Gollan, John (1911-1977)

Born 1911, in Edinburgh, of socialist parents, Gollan—a sign writer in his youth—was involved in socialist and Communist Party activity in the city from an early age. His first political activity was selling bulletins during the 1926 General Strike. He joined the Young Communist League and the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1927. In July 1931, he was arrested for selling papers to soldiers and sentenced to six months solitary confinement. A mass campaign developed in Edinburgh in support of him, culminating in a demonstration of some 5,000 supporters.

Born 1911, in Edinburgh, of socialist parents, Gollan—a sign writer in his youth—was involved in socialist and Communist Party activity in the city from an early age. His first political activity was selling bulletins during the 1926 General Strike. He joined the Young Communist League and the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1927. In July 1931, he was arrested for selling papers to soldiers and sentenced to six months solitary confinement. A mass campaign developed in Edinburgh in support of him, culminating in a demonstration of some 5,000 supporters.

He went on to be successively editor of the Young Communist League’s newspaper Challenge in 1932 and General Secretary of the League in 1935. His book, Youth in British Industry (1936) was a choice for the Left Book Club, which analysed the fundamental changes in the workforce that were affecting youth.

Gollan was the Communist Party District Secretary for the North East England from 1939 and then for Scotland in 1941. He was appointed Assistant General Secretary of the Party in 1947. From 1949 to 1954 he was assistant editor of the Daily Worker. The role of National Organiser followed in 1954 and General Secretary, succeeding Harry Pollitt from 1956-1976.

by Graham Stevenson

See John Gollan Archive.

Gompers, Samuel (1850-1924)

Samuel Gompers was born in London, England, on 27th January, 1850. His emigrated to the United States in 1863 and the family settled in New York City. Gompers and his father worked as cigar makers. After attending a lecture in 1879 given by Thomas Hughes the British M.P. and Christian Socialist, Gompers became an active trade unionist and helped to reorganize the Cigarmaker's Union.

Samuel Gompers was born in London, England, on 27th January, 1850. His emigrated to the United States in 1863 and the family settled in New York City. Gompers and his father worked as cigar makers. After attending a lecture in 1879 given by Thomas Hughes the British M.P. and Christian Socialist, Gompers became an active trade unionist and helped to reorganize the Cigarmaker's Union.

In 1881 the Federation of Trades and Labour Unions (ATLU) was founded. This organisation was based on the structure of the Trade Union Congress in Britain. Gompers was the chairman of this new organisation and when it changed its name to the American Federation of Labour in 1886, he was elected its first president.

Gompers held conservative political views and believed that trade unionists should accept the economic system. As a result, a rival, more radical organisation, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was formed. However, numbers of members remained small compared to American Federation of Labour.

Gompers supported United States involvement in the First World War and became a member of the Council of National Defense. In 1919 Woodrow Wilson appointed Gompers as a member of the Commission on International Labour Legislation at the Versailles Peace Conference.

Samuel Gompers, who was president of the American Federation of Labour from 1886-1894 and 1896-1924, died in San Antonio, Texas on 13th December, 1924. His autobiography, Seventy Years of Life and Labor (1925), was published after his death.

From http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USAlewisJL.htm

See Samuel Gompers Eight Hours

Gomez, George (1927-present)

Born in a fishing village in Madras Presidency (now Tamil Nadu), son of progressive Catholic parents. Moved to Ceylon after finishing school. Joined Bolshevik Leninist Party of India, 1948. Moved to Bombay, became a dock worker, and union activist for thr rest of his political career. Resides in Thoothukudi (Tuticorin), Tamil Nadu.

Compiled by Charles Wesley Ervin

Gomulka, Wladyslaw (1905-)

Became leader of Polish Workers Party in 1943 under the Nazi occupation, and remained the most popular leader in post-War Poland. Removed under Soviet pressure after he objected to the 1948 left-turn, in particular the proposed forced collectivisation of agriculture. At the peak of the European political revolution, Gomulka was restored to leadership, and negotiated a compromise between Khrushchev and the Polish workers. While Gomulka organised the repression of the Warsaw students in 1968, he is generally believed to have opposed, though in vain, the subsequent upsurge of anti-Semitism in the leadership of the Polish CP. A true Polish nationalist, Gomulka was however no democrat and preferred personal control to delegation. Finally discredited after ordering the use of force against Gdansk strikers in 1970 and replaced by Edward Gierek.

Goonewardene, Cholomondeley (1917– 2006)

Born Kalutara, Ceylon, son of Muhandiram Arnold Goonewardene, a wealthy landowner and local leader (muhandiram ) originally from Panadura. Educated Holy Cross College, Kalutara, and St. Thomas’ College, Mt. Lavinia. Joined Lanka Sama Samaja Party, 1937. Entered the Kalutara bar, 1946. Affiliated with the LSSP (Philip Gunawardena-N.M. Perera) in the post war split, 1945-50. Member, Kalutara Urban Council, 1940-70, and Chairman 1954-56 and 1963-64. Member of Parliament (Kalutara Constituency), 1947-52 and 1956-77. Minister, Public Works, LSSP-SLFP coalition government, 1964. Left LSSP, 1982; formed rival Sri Lanka Sama Samaja Party. Deputy President, Sri Lanka Mahajana Party (formed in 1985).

Compiled by Charles Wesley Ervin

Goonewardene, Leslie Simon (1909– 1983)

Party pseudonyms: Tilak, V.S. Parthasarathi.

Born Panadura, Ceylon, son of Andrew Simon Goonewardene, a popular doctor in the area. Educated St. John’s College, Panadura, St. Thomas’ College, and a public school in North Wales. Earned B.Sc. in Economics, London School of Economics. Read law at Gray’s Inn; admitted to the bar, 1933. Returned to Ceylon, 1933. Secretary, Lanka Sama Samaja Party, 1935-77. Delegate to Indian National Congress, Tripuri, 1939. Sent to Bombay, 1941. Member Provisional Committee, Bolshevik Leninist Party of India, 1942. National Secretary, BLPI, 1942-44; worked in BLPI groups in Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta, 1941-46. BLPI Central Committee, 1944-47. Attended BLPI conferences, 1947 and 1948. Editor, Bolshevik Leninist , 1942-43. Editorial Board, New Spark , 1947-48. Alternate member, International Executive Committee of FI, 1948. Member of Parliament, 1956-60. Minister of Communications, LSSP-SLFP-CP United Front coalition government, 1970-75. Author: From the First to the Fourth International (1944), The Rise and Fall of the Comintern (1947), Open Letter to Socialist Party Members: The Coming Crisis in the Socialist Party (1947), The Differences Between Trotskyism and Stalinism (1954), What We Stand For (1959), and Short History of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (1960).

Compiled by Charles Wesley Ervin

Goonewardene, Violet Vivienne (1916– 1996)

Party pseudonym: Ashok Kumari Tilak

Born Colombo, Ceylon, daughter of Dr. Don Allenson Goonetilleke and Emily Angeline Gunawardena, sister of Philip and Robert Gunawardena. Educated Musaeus College, Colombo. Participated in Suriya Mal movement. Worked on Straight Left . Joined Lanka Sama Samaja Party. Delegate to Indian National Congress, Tripuri, 1939. Married Leslie Goonewardena, 1939. Sent to India, 1941; worked in Bolshevik Leninist Party of India groups in Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta, 1941-46. Author: “Rosa Luxemburg—The Legend and the Truth” (Permanent Revolution , vol. 1, no 3, 1943). Returned to Ceylon, 1946. Municipal Councilor, Colombo, 1949-54 and 1960-69. Vice President, All-Ceylon Congress of Samasamaja Youth Leagues. Member of Parliament, 1956-60, 1964-65, 1970-77. Junior Minister, SLFP-LSSP coalition government, 1973. President, All-Ceylon Local Government Workers’ Association.

Compiled by Charles Wesley Ervin

Gorbachev, Mikhail (1931-)

Studied law at Moscow University; joined the Party in 1952 at age 21; began as a district organiser of the CPSU in Stavropol from 1970 to 1978. He was elevated to the Politburo in 1979 where he received the patronage of Yuri Andropov, head of the KGB and also a native of Stavropol, and promoted during Andropov's brief time as leader of the Party before his death in 1984. After the death of the ageing Chernyenko, Gorbachev became General Secretary of Party in March 1985. Gorbachev launched his campaign for glasnost (openness) and perestroika. (restructuring) at the 27th Congress of CPSU in February 1986. After the break up of the USSR in 1991 Gorbachev commented: 'The main work of my life is done. I have done all that I could, I think that in my place others would have given up long ago. But I managed to drag the idea of perestroika through, if not without mistakes... [the CIS] have begun carving up the country like a pie'. The final session of the Congress of the USSR was legally without the number of members required to make any decision valid. In adjourning the session, Gorbachev commented 'I respect your decision, but please carry on without me'. Gorbachev was seen from the West as a driving force for change in the Soviet Union. Gorbachev later made television commercials to sell western products around the world; among them such fast food restaurants as Pizza Hut.

Studied law at Moscow University; joined the Party in 1952 at age 21; began as a district organiser of the CPSU in Stavropol from 1970 to 1978. He was elevated to the Politburo in 1979 where he received the patronage of Yuri Andropov, head of the KGB and also a native of Stavropol, and promoted during Andropov's brief time as leader of the Party before his death in 1984. After the death of the ageing Chernyenko, Gorbachev became General Secretary of Party in March 1985. Gorbachev launched his campaign for glasnost (openness) and perestroika. (restructuring) at the 27th Congress of CPSU in February 1986. After the break up of the USSR in 1991 Gorbachev commented: 'The main work of my life is done. I have done all that I could, I think that in my place others would have given up long ago. But I managed to drag the idea of perestroika through, if not without mistakes... [the CIS] have begun carving up the country like a pie'. The final session of the Congress of the USSR was legally without the number of members required to make any decision valid. In adjourning the session, Gorbachev commented 'I respect your decision, but please carry on without me'. Gorbachev was seen from the West as a driving force for change in the Soviet Union. Gorbachev later made television commercials to sell western products around the world; among them such fast food restaurants as Pizza Hut.

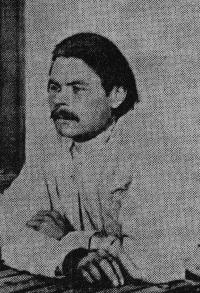

Gorky, Maxim (1868-1936)

Maxim Gorky was a founder of Soviet literature and the author of

world-famous works such as Mother, Childhood, My Apprenticeship, My

Universities, The Life of Klim Samgin and many plays, stories and

publicistic articles.

Maxim Gorky was a founder of Soviet literature and the author of

world-famous works such as Mother, Childhood, My Apprenticeship, My

Universities, The Life of Klim Samgin and many plays, stories and

publicistic articles.

Destitute as a youth, became Russia's foremost writer; he joined the Bolshevik party in 1905 and helped organise their first legal newspaper, but drifted away during the first world war.

In 1905, the first meeting between Lenin, leader of the Russian Revolution, and the great proletarian writer took place in St. Petersburg. Maxim Gorky came to know Lenin more closely in 1907 at the London Party Congress, of which he has written a detailed description. These two men were linked by true friendship and profound mutual respect. Lenin highly appreciated Maxim Gorky's work. "There can be no doubt," he wrote in 1917, "that Maxim Gorky's is an enormous artistic talent which has been, and will be, of great benefit to the world proletarian movement.

Gorky opposed the revolution in October 1917 and left USSR in 1921, but returning in 1931, he accommodated himself to Stalin.

See Maxim Gorky Archive.

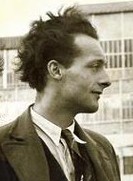

Gorter, Herman (1864-1927)

Herman Gorter was born on November 26, 1864, the son of a famous Dutch litterateur. He was keen student of the classics and became a teacher of Greek and Latin. Gorter created a great stir with his poem, May, which expressed a worship of nature in a language never heard before. He broke with tradition and established rules and expressed the feelings as they were actually felt. In 1880, Gorter gathered about him a group of young poets and developed the literary revolution known as “the movement of the Eighties.”

Herman Gorter was born on November 26, 1864, the son of a famous Dutch litterateur. He was keen student of the classics and became a teacher of Greek and Latin. Gorter created a great stir with his poem, May, which expressed a worship of nature in a language never heard before. He broke with tradition and established rules and expressed the feelings as they were actually felt. In 1880, Gorter gathered about him a group of young poets and developed the literary revolution known as “the movement of the Eighties.”

But Gorter soon perceived that this movement did not go very far and he turned to a study of ancient of Greek and Egyptian culture to understand the reason of their powerful development. The result was expressed in an essay: Critique of the movement of the Eighties.

Gorter studied philosophy, translating Spinoza’s Ethics, studying Immanuel Kant and finally reading Marx’s Capital. In Marx he had found what he wanted and he began a deep study of the writings of Marx and Engels.

In 1890, Gorter joined the social Democratic Labour Party in Holland, S.D.A.P. At first the party rejoiced in his membership, but he soon found himself in conflict with the Party leadership. Nevertheless, he emerged as a great marxist theoretician and one of the most powerful speakers in Holland. Het Volk, the social democratic organ, complained that socialism was, to him a fine dream, an unattainable utopia. He was a clear and convincing speaker, they said, but he disrupted the party with his accusations of political corruption and careerism.

As the tendency towards reformism became more marked in the S.D.A.P.. Gorter exposed the capitalistic compromises and treacheries of the S.D.A.P. and the fight became very sharp. A marxist group was formed within the S.D.A.P., but most of this group was expelled in 1909 and formed a Marxist party under the title of the SPD (Sozialistische Partei Deutschlands, Social-Democratic Party) . Gorter joined the SDP.

That year the SDP published Gorter’s work, Marxism and Revisionism, defending Marxist ideas against Bernsteinian revisionism, and supporting the SDP’s analysis of capitalist society. At the outbreak of the First World War, the SDP leaders, Winjnkoop and Ravensteijn, were elected to Parliament. The unionised workers of Holland, the mass base of the SDP, were in a majority opposed to “Prussianism” and inclined to sympathy with “allied” imperialism. As a result of this pressure, Winjnkoop and Ravensteijn upheld the “allied cause” in Parliament .

When the world war broke out, Herman Gorter opposed the way in which the leaders of Social Democracy placed itself at the disposal of “their own” bourgeoisie. He analysed the causes of the collapse of the socialist movement, in his work, Imperialism, Social Democracy, and World War.

Gorter showed that it made no difference to the workers which of the imperialist alliances won the war. For the workers in all lands the issues remained the same. Imperialism was not destroyed by capitalist wars. There was only one way in which the workers could destroy Imperialism: that was the way of World revolution.

The Russian Revolution of October 1917, found in Gorter an enthusiastic defender. Gorter held that to triumph, the revolution had to be a world revolution.

With his friend, Anton Pannekoek, Gorter analysed the Russian Revolution in terms of historical materialism. They show how this revolution was in part a proletarian, and in part a peasant, and therefore bourgeois revolution. The peasants desired and private property and division of the land. Against 10 million workers, inclined to socialist understanding, there were over 100 million peasants, with capitalistic ideology. If the world revolution all the proletariat came to help, these ten millions would become part of the mighty proletariat that conquered and emancipated the world. But if they world revolution did not come to the aid of the Bolsheviks, then it was determined by the class conditions existing in Russia that a new capitalist period would set in. And the consequence would be that Russia would change from being the centre of world revolution, into a powerful ally of world Capitalism, allied to other capitalist states, in enmity to the working class struggle.

In 1921, Gorter travelled illegally to the Third Congress of the Third International, as a delegate of the K.A.P.D. Lenin had published his work “Left-Wing” Communism an Infantile Disorder, cautioning against attempts to replicate the Russian Revolution in Europe without the necessary conditions and preparation.

Gorter opposed the analysis Lenin made in this work. He responded with a pamphlet entitled Open Letter to Comrade Lenin claiming that Lenin’s strategy of compromise with the peasantry must lead to the failure if applied to Western Europe and therefore undermine the world struggle for socialism. Leninism, he held, would prolong the struggle and increase the cost in suffering and hardship to the workers.

In opposition to what he saw as a Leninist “dictatorship over the proletariat,” and reduction of the Communist Parties to “legal” parties, Gorter developed left wing tactics anti-Parliamentarism. Gorter saw the construction of workers’ councils (soviets) as an achievement of the workers’ movement itself, not that of theoreticians, and declared that every period of the class struggle has its own laws, according to which the rank-and-file develops its own forces. The workers had discovered that in those countries where they had built parliamentary parties and trade unions, these same organisations opposed every proletarian action. Thus, the shop committee (or council, or soviet) became, in Gorter’s view, the form in which the proletarian consciousness found its expression.

Gorter thought that Lenin did not understand the different conditions in the West, and, therefore, erred in the tactics he urged on the workers of Western Europe.

Gorter and Pannekoek developed the theoretical statement of the Left Wing. They declared that in the West the proletariat is the only power for revolution, and must grow in class consciousness and power consciousness. Parliamentarism must be destroyed as the safety valve of class society, and trade unions must be repudiated as parliamentarism on the industrial field, an extension bourgeois society. The Left-wing would not except the 21 points for admission to the Communist International, and was expelled. But Gorter viewed the breaking down of the Third International as inevitable, but saw communism as certain to revive and eventually triumph.

Herman Gorter died in Brussels on September 15, 1927. He had gone to Switzerland from his home in Holland to renew his health, but he felt that the end of his life was near, and so he broke off his stay in Switzerland and tried to return home. But he was obliged to break his journey at Brussels, and died the same night in the hotel. He spent his last ten hours making arrangements for his unpublished writings and issuing strict instructions that nobody should speak at his grave.

Gorz, André (1923-2007)

French writer and philosopher. Born Gerhard Hirsh in Vienna, he spent the war years in Switzerland, moving to Paris in 1949. After working for the pacifist group Citizens of the World, Gorz entered journalism, working for Paris -Presse until he was hired by L’Express in 1955. In 1961 Gorz joined the editorial committee of Sartre’s Les Temps Modernes, which he became editor of in 1969. His article “Destroy the University” in 1970 led to the resignation of two members of the editorial committee, and in 1974 Gorz himself left the journal over an issue dedicated to the Italian ultra-Left group Lotta Continua.

French writer and philosopher. Born Gerhard Hirsh in Vienna, he spent the war years in Switzerland, moving to Paris in 1949. After working for the pacifist group Citizens of the World, Gorz entered journalism, working for Paris -Presse until he was hired by L’Express in 1955. In 1961 Gorz joined the editorial committee of Sartre’s Les Temps Modernes, which he became editor of in 1969. His article “Destroy the University” in 1970 led to the resignation of two members of the editorial committee, and in 1974 Gorz himself left the journal over an issue dedicated to the Italian ultra-Left group Lotta Continua.

By the late ’60s Gorz was already involved in an alternative vision of the Left less interested in the working class than the classical Left, and by the ’70s he was an important and influential voice in what would later develop into the Green movement.

His final book was the moving “Lettre ŕ D.,” his homage to his gravely ill wife of over fifty years, Dorine. Its final lines were: “Neither of us would want to survive the other. We often said that if it were someway possible to have a second life, we would want to live it together.” On September 22, 2007, they committed suicide together.

Gotz, Abram Raphailovich (1882-1940).

Leader of the Socialist Revolutionary fraction in the Petrograd Soviet in 1917. Opposed October Revolution and fought Soviets till 1920. Condemned to death 1922, freed, re-arrested in 1937 and sentenced to 25 years captivity.

Leader of the Socialist Revolutionary fraction in the Petrograd Soviet in 1917. Opposed October Revolution and fought Soviets till 1920. Condemned to death 1922, freed, re-arrested in 1937 and sentenced to 25 years captivity.

Gould, Bob (1937-2011)

Australian Trotskyist who introduced a new generation to Marxism in the 1960s and was renowned for the Left bookshop he ran in Sydney.

Australian Trotskyist who introduced a new generation to Marxism in the 1960s and was renowned for the Left bookshop he ran in Sydney.

Born in 1937 into an Irish Catholic family, Bob saw himself as a child of 1917-1918: ‘the years of the Russian Revolution, the conscription referendum, my grandfather standing for parliament, the great strike, and the year my dad was blown up in the first great imperialist war’.

He joined the ALP in 1954 at the age of 17 and threw himself into the battle against the Groupers, learning invaluable lessons about the labour movement which would stay with him for the rest of his life. Bob was a lifelong member of the ALP, campaigning for socialist policies at every opportunity, fighting to maintain the party’s trade union base and urging close cooperation between Labor and Green members. He memorably attended the 1971 ALP Federal Conference on behalf of the Socialist Left.

Among decisive moments in his political life he included his major role in the movement against the Vietnam War, a seven-year campaign which finally led to the withdrawal of Australian troops.

He also included his break with Stalinism after Kruschev’s secret speech of 1953. Influenced by Nick Origlass and Issy Wyner, he became active in the Trotskyist movement. He denounced the crushing of the Hungarian Revolution by Soviet tanks in 1956 and every later effort by supporters of the Moscow bureaucracy to cover up its counter-revolutionary role. For him Stalinism represented a ‘monstrous perversion of the socialist project’.

He always stood for greatest unity in the struggle against capitalism and fought to overcome the splits in the Trotskyist movement, both in Australia and internationally. Instead of splits he advocated measures such as public factions and a broad political discussion across the left.

Bob was an excellent polemicist and in later years used various left-wing websites as major vehicles for his views and he contributed over 330 articles in a ten-year period to Ozleft alone. His articles covered a wide range of topics, including theoretical issues in Marxism, book reviews and ongoing polemics with a number of left groups. Throughout he maintained principled positions on every major political issue.

He was also a highly-skilled orator who could intervene at decisive points in meetings, often to the considerable displeasure of his political opponents.

One of Bob’s great strengths was his knowledge of the history of the labour movement in Australia and internationally and he continually urged younger activists to study and learn from this rich, and at times contradictory, body of experience: he had no time for empty sloganising.

Bob had a deep love of books and his bookshops reflected his wide-ranging interests. He carried an invaluable collection of labour movement material, much of it difficult to find anywhere else.

Revolutionary, Trotskyist, lifelong ALP member, polemicist, agitator, orator, raconteur, anti-censorship campaigner, lover of books, an atheist from an Irish Catholic background and much more: Bob Gould was full of life and passion and he will be sorely missed.

His long-time comrades Nick Origlass, Issy Wyner and George Petersen are no longer with us and now Bob’s death marks another stage in the struggle for socialism in Australia.

See Bob Gould Archive.

Obituary by Phil Sandford, 23 May 2011

Govindarajulu, C. (? - present)

Born Vadugapatti (Theni District, Tamil Nadu), son of prosperous landowners. Educated Madurai College. Recruited to Trotskyism by the Lanka Sama Samaja Party field organizers sent to Madurai, V. Balasingham and B.M.K. Ramaswamy, 1941. Arrested and jailed. Joined Bolshevik Leninist Party of India in Madurai, 1942. Joined SP with BLPI, 1948. When SP merged with KMPP, remained with the dissidents. Elected member of the Madurai District Ad Hoc Committee for the SP (Loyalists), September 1952. Delivered Presidential Address at the SP (Loyalists) conference in Madurai, November 2, 1952. Elected Convenor, Madurai District Ad Hoc Committee for SP (Loyalist). Pesident, Bellary District [Karnataka] Motor Workers union. Survives on his Freedom Fighters’ Pension. Resides in ill-health in Madurai.

Compiled by Charles Wesley Ervin