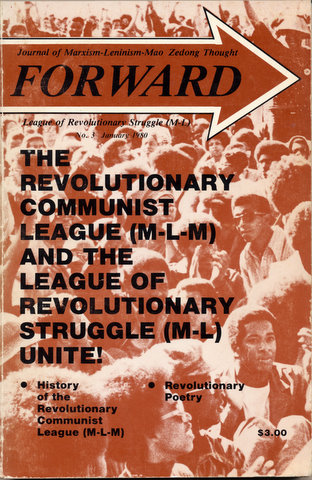

First Published: Forward, No. 3, Jauary 1980.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

Two major Marxist-Leninist organizations, the Revolutionary Communist League (M-L-M) and the League of Revolutionary Struggle (M-L), have united into one organization, the League of Revolutionary Struggle (M-L). This is a significant step forward in the struggle for Marxist-Leninist unity and the U.S. revolutionary movement.

The RCL and the League carried out a process of principled struggle for unity, a process which integrated joint discussions on theoretical questions and joint practice. The two organizations also summarized their histories. Throughout the unification process, the two organizations desired unity, adhered to Marxist-Leninist principle, and practiced criticism and self-criticism. As a result, they were able to resolve their differences and reach unity on all major points of political line.

RCL and the League had substantial political unities which in part reflected the similarity of the two organizations. Both RCL and the League have their origins in the mass movements of the oppressed nationality peoples of the 1960’s, and over the years carried out extensive work among the masses. While there were also differences in each organization’s development, each organization has a rich and complex history, having grown and deepened their understanding of making revolution and Marxism-Leninism through a process of twists and turns.

From the beginning of the merger process, RCL and the League had unity on the national question in the U.S. Both upheld the view that the national movements are a powerful revolutionary force and a component part of the socialist revolution. Both upheld in theory and in practice the right of self-determination for the Afro-American nation in the Black-belt South and for full and equal rights for Afro-Americans in the North. RCL and the League had unity in their view of self-determination and equal rights as democratic demands that can only be won through a revolutionary struggle for political power. The two organizations also united in seeing the necessity for building a broad united front within the national movements and waging a class struggle in the national movements for communist leadership. RCL and the League also were united in their view of the oppressed Chicano nation in the Southwest with the right to self-determination.

RCL and the League also had unity on the international situation and adherence to the theory of the three worlds; support for socialist China and the Communist Party of China under the leadership of Chairman Hua Guofeng; a general line on labor and trade union work; and other questions, including the need for communists to improve their work around the woman question.

These unities provided a strong basis to struggle over the differences, separating major and minor points, to forge a solid and principled basis for unification.

In the merger process, RCL and the League also resolved differences through criticism and self-criticism and pinpointed weaknesses in each of the two organizations.

In the course of RCL’s history of taking up Marxism-Leninism there were twists and turns and mistakes were made, such as certain tendencies of mechanicalness and abstractness and “left” line influenced by the “Revolutionary Wing.” By 1976 RCL was able to criticize the “Wing” and committed itself to the break with ultra-leftism. But this occurred in the course of struggle and there were remnants of these weaknesses that still existed. For example, on party building, while under the influence of the “Wing’s” line, RCL did not pay enough attention to practice and building mass ties. These are component parts of party building dialectically related to the struggle to develop a living line of the U.S. revolution and to uniting Marxist-Leninists. These errors were criticized in the merger process and unity was reached on the view of party building.

The League recognized that it had not paid enough attention to its theoretical work and that its newspaper, UNITY, needed more theoretical articles. This reflected a weakness of not taking up the struggle to win over independent Marxist-Leninists and make a general presentation of its line in the newspaper. These errors were summed up in the merger process.

As the political unity between RCL and the League increased, they tested unities and strengthened their ties through joint work. The two organizations worked together in the Anti-Bakke Decision Coalition (ABDC); the New York tour of the United League; and in the Baraka Defense Committee. This committee was formed to bring justice for Amiri Baraka who was beaten by the New York City Police, as well as to generally educate and organize people against police brutality and Black national oppression.

One of the significant parts of the unification of RCL and the League was the affirmation of their histories, in particular the summarization of the history of RCL.

At the time of the merger of the August 29th Movement (M-L) and I Wor Kuen to found the League of Revolutionary Struggle (M-L) in 1978, ATM and IWK both summarized their histories as an important part of the history of the entire revolutionary and communist movements. They affirmed the overwhelmingly positive contributions of the two organizations which grew out of the Chicano and Asian national movements; took up Marxism-Leninism-Mao Zedong Thought; and carried out communist work in the working class, national movements, student movement and other sectors. They also criticized weaknesses and errors made, as a way of learning from past experience.

Since its founding the League has grown as a nationwide, multinational organization that has made some important strides forward. Its newspaper, UNITY, is now published biweekly. The League also has a theoretical journal, FORWARD, which has included a major position on the Chicano national question. The League also broadened its work in the working class and national movements as well as among other sectors, and has also made principled efforts to unite with other Marxist-Leninists towards forging a single, vanguard party.

RCL has nearly 15 years experience in the Afro-American people’s struggle for self-determination, for equal rights and against national oppression. RCL has its roots in the Black Liberation Movement of the 1960’s when the Afro-American people rose up in a storm of struggle against their national oppression, shaking U.S. monopoly capitalism at its foundations. Many revolutionary fighters and organizations came forth during this period even though there was no genuine communist party to lead the masses.

RCL grew out of the Congress of Afrikan Peoples (CAP), one of the major revolutionary nationalist organizations of the Black Liberation Movement between 1970 and 1974. The main predecessor of CAP was the Committee for a Unified Newark (CFUN), a community-based group in Newark, New Jersey, which was organized in 1967 by Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), a leading Black revolutionary playwright and poet. The CFUN took up mass struggles, built mass “alternative” programs like its Afrikan Free School, and also played a major role in the 1970 election of Kenneth Gibson, the first Black to be elected mayor of a major northeastern city.

The founding of the Congress of Afrikan Peoples in Atlanta in 1970 was attended by 3,000 people, representing a broad cross section of the mainstream Black Liberation Movement and community; and was attended by mass activists, and well-known and diverse personages like Julian Bond, Jesse Jackson, Owusu Sadaukai and Louis Farrakhan. CAP brought together in a national organization some of the major currents of the cultural nationalist and Pan Africanist trends of the Black movement, with hundreds of revolutionary and progressive activist cadre in chapters in 17 cities.

CAP engaged in many mass struggles, some of the most well-known of which were the Stop Killer Cops campaign, carried out in 12 cities, and the fight for Kawaida Towers in Newark as a low-and medium-income housing project for Blacks and Puerto Ricans.

CAP also played a major role in broad united front work such as the first National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana, in 1972, which was attended by 8,000 people; and the National Black Assembly (NBA) of which Amiri Baraka was the Secretary General until 1975. CAP also did extensive work in organizing the African Liberation Support Committee (ALSC), along with other forces, to support the liberation struggles in Africa.

CAP published a newspaper Black Newark and then Unity and Struggle that had a distribution of as high as 12,000.

As a cultural nationalist and Pan Africanist formation arising directly out of the mass movement of the 1960’s, CAP fought on the side of the masses, and stood openly for revolution and an end to national oppression. But it did not have a scientific ideology guiding its work until 1974. CAP erroneously believed that white people are the enemy of Blacks. It also had certain reformist tendencies, such as its tendency to view gaining Black political power through the electoral process. This was due, in part, to CAP’s desire to unite broad sectors of the Black movement and to seek alternatives to the reactionaries in power like the notorious racists Addonizio and Imperiale in Newark. But CAP learned from its own experience that the election of Blacks into political office did not fundamentally change the conditions of the masses, and that the upper stratum of the Black bourgeois politicians, more often than not, actually sided with the bourgeoisie against the mass movement of their own people. At the same time, CAP gained significant experience in major electoral political campaigns.

Through its work and experience, CAP gradually broadened its political outlook and gained a more scientific understanding of the conditions of the Afro-American struggle and its relationship to the international and domestic revolutionary struggle. CAP began to study Marxism-Leninism in 1974, and in that year, summarizing its own experience and influenced by struggle in the NBA and ALSC, adopted Marxism-Leninism-Mao Zedong Thought as its ideology. This was a major turning point for the organization. CAP, and later RCL, went through a process of transforming itself into a communist organization.

As a communist organization RCL did work in a number of midwestern and northeastern cities and made contributions to the developing communist movement. It continued its involvement in the mass struggles of the Afro-American people, including work against police brutality, against national oppression in education, the building of the Black Women’s United Front (a mass organization of Black women) and revolutionary cultural work. RCL also developed work in the industrial working class. It continued to publish Unity and Struggle and also made important theoretical contributions in applying Marxism-Leninism to the U.S. revolution on the Afro-American national question.

In late 1975-76, RCL came under the influence of the ultra-left line supported by the “Revolutionary Wing.” Later it struggled to break with the “Wing’s” influence and establish a more correct orientation and line.

The history and development of CAP/RCL provide valuable lessons on revolutionary work in the Black Liberation Movement. They have gone through a process of struggle to recognize the path which will lead to winning Black liberation and the overthrow of imperialism – the path of Marxism-Leninism. They have learned many lessons. They have also made contributions to the Black Liberation Movement in the U.S., a struggle which is vital and a component part of the U.S. revolution.

The merger of RCL and the League means it will be possible to broaden the scope of work and to do more to take up the struggles of the masses, to integrate Marxism-Leninism with the concrete practice of the U.S. revolution, and to seek unity with other Marxist-Leninists towards forging a single party. The League has a wealth of experience, and its cadre have been tempered in the heat of class struggle. At the same time the League recognizes that there is a continuing struggle against weaknesses, and that much needs to be done to improve its theoretical work and newspaper work; to deepen its ties with the masses and to improve its united front work; and to play an active and aggressive role in fighting opportunism and uniting Marxist-Leninists in party building.

As was presented in a statement by the Central Committees of the RCL and League upon the two organizations’ merger, “Our unity signals a big advance in the struggle for Marxist-Leninist unity and for a single, unified, vanguard communist party. It represents a strengthening of the communist forces and a blow against revisionism, Trotskyism and opportunism .... Both our organizations have rich histories and experience in the U.S. revolutionary movement. There are many similarities in our histories, as well as differences in the way we developed. In the course of our unity talks, the histories of both organizations have been affirmed, and we are determined to carry on the revolutionary tradition and Marxist-Leninist stand and attitude in the ranks of a single organization, the League of Revolutionary Struggle (M-L).”