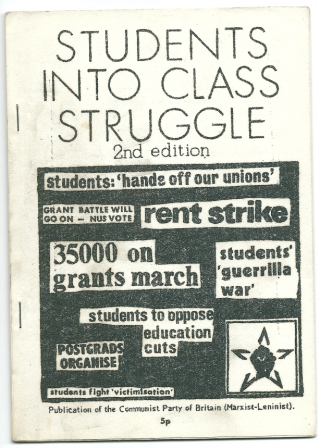

First Published: 1971. [This version from the Second Edition].

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

This pamphlet represents the collective experience of comrades of the Communist Party of Britain (Marxist-Leninist) engaged in struggle on the student front. It is an application of the line of the Party embodied in its Programme “The British Working Class and Its Party”.

The only purpose of this pamphlet, being a theoretical one in its true sense, i.e. derived from practice, is as a guide to action, to develop the struggle of students by deepening it and broadening it in a political way.

It is not intended to be, indeed it cannot be, a blueprint or list of formulae for would-be Marxist “mechanics”, to go through the motions of acting out.

Much thought has gone into its production and even more thought must be given to its creative application. This being the case we are confident that we as students with the leadership of the Party can play our part in the struggle of our class to smash capitalism and build socialism.

In the three years since this pamphlet was first written, the struggle amongst students has developed enormously. The quality and character of the battles has improved, touching new sections and areas never before drawn into action. From the fight against the Thatcher proposals (the student equivalent of the Industrial Relations Act) to the continuing grants campaign, and in numerous local disputes and battles, we have gained also a wealth of experience from which we can further develop our theory.

Three years’ experience has shown that the original “Students Into Class Struggle” fulfilled the Marxist principle of “Practice, Theory, Practice”, for it is as true and accurate today as when it was first published, and has successfully been put into practice.

Yet practice is the greatest teacher, and never ceases to provide more lessons and, if considered correctly, a better understanding. So the pamphlet has been updated, strengthened and broadened to improve its value to all who are or are becoming involved in the student movement.

Education in Britain is now being dismantled.

It is no longer a good investment. Profits are greater abroad, the workers less well organised, less of a threat. British capital is therefore flowing to these areas. So what is the point of training workers here when there will be no industry for them to run, when such an education might give them expectations beyond their future place in life!

Yet the greatest asset for any nation is its people’s skill, ingenuity and knowledge. The means of passing these on and developing them is now being wrecked by tile capitalist class.

The only solution open to us is to wreck these wreckers, destroy them, and replace their rule with our own socialist rule. The fight against the cuts are part of this revolutionary battle.

The defence of health and education is the responsibility of the whole working class. In higher education students are necessarily in the front line, but to be effective we need a unity of all working in education.

Without a clear understanding of basic questions – where do students stand in today’s society, what contributions can they make, how should they strive to develop their struggle and with what sort of perspective? – we will hesitate and flounder in confusion. And the capitalist class will gain and keep the initiative, forcing us into a passive situation.

In this revolutionary situation the lessons of this pamphlet are more important than ever. We must all learn them well and apply the lessons to the developing struggles.

W R E C K THE W R E C K E R S !

* * *

The past few years have seen-the appearance of a new phenomenon, that of student struggle becoming a regular occurrence. Significant numbers of students have now been forced into conflict and ferment as they find themselves in growing contradiction with the system itself and the educational system in particular. A qualitative change has, and is taking place among students and the system of capitalism is weaker for it.

No longer can students be used as a force to scab on workers’ strikes – no longer can the ruling class expect and rely on students to operate as a reactionary shock force in times of social conflict and crisis, as they did as volunteers in the 1926 General Strike though the bourgeoisie will try to develop such action. In this respect times have changed. Of course, the level and frequency of struggle, as well as the numbers of students involved, has varied from college to college and between the different types of educational institutions – the Polytechnics, the Colleges of Education, the Universities, the Technical Colleges, and so on. In some places, maybe little or nothing has yet occurred. However, the change is basic, and continuing and growing action is the trend, ensuring that in the present crisis 1926 shall not be repeated.

But a qualification is that students are relatively new to struggle and inexperienced in it. Further we enter it with many disadvantages and weaknesses – which of course has never been an argument not to fight, only to give more consideration and thought to it. In composition our section is transient and continually changing each year. In power and bargaining strength we seem to be weak; our organisations are young and the development of strong student unions recent and uneven. Yet in the building of true unions, the student movement has moved on from the early battles of the late sixties: sporadic, uncoordinated and with little concerted effort, struggles which were engaged in without enough understanding of students actually as a force in serious battle, without enough involvement indeed of the student mass and without enough consideration being given to good tactics and strategy.

To help develop further the qualitative change taking place, students must have a clear understanding of their position in Britain, examine their contradiction as a force with the ruling class and capitalism, understand the need for the leadership and organisation of the true Marxist-Leninist Party involved in this student struggle, and how this fight is to be developed so that students see it as a component part of the fight of the entire working class, the force that alone can destroy capitalism.

Before coming in detail to the struggle of students and the role of our Party in it, we must dispense with notions that have wreaked much confusion, the notions that students are middle class or indeed classless. The supporting argument to these notions is that students are privileged because they are getting education and also because of the opportunities it opens up in the way of employment and job. But the argument holds water only if it is left stated and unanalysed and if reality is left out of the picture somehow – which of course is impossible.

What is the actual position of students in this the oldest and most proletarianised of capitalist countries, Britain? Britain has only two classes – those who sell their labour power and those who exploit the labour of others. All those intermediate classes, such as the peasantry, that were left over from feudalism have been absorbed into the proletariat. Students do not own the means of production and are not going to exploit the labour of others.

Capitalism in its anarchy and inefficiency may train some students only for the dole queue, and produces many who can make no use of what they have learnt in later employment. Nevertheless the educational system serves its broad purpose for capitalism – the training of hundreds of thousands of students, who are in an educational apprenticeship, acquiring and being taught skills for future employment and jobs. Many (such as student teachers) have to give many days and weeks of unpaid labour as part of this apprenticeship.

After finishing their education students are going to be wage slaves of capitalism, generally in the white-collar and professional areas where recently a growing trade union development has occurred, among draughtsmen, technicians, scientific workers, teachers to name but a few. Many students are already seeing that they will be wage earners pure and simple, and often badly paid at that. That is if they are lucky; for with the application of rationalisation and productivity workings by management to white-collar and professional areas, students are rapidly becoming a new unemployed that capitalism has created. Qualifications are no passport to success and a way out of the class struggle any longer, if they ever were.

Indeed the whole idea that education was a privilege granted by capitalism was superficial and mistook what was happening. A brief reflection on the fact that students are paid according to the absolute minimum thought necessary to exist, and moreover are forced into a dependent relationship with their parents or spouses into the bargain, should be enough to squash such notions for ever. Capitalism did not erect the educational system because it liked the idea of people getting cultured for the sake of it, out of a altruism or philanthropy; rather because capitalism had need of it, it needed skilled workers, scientific and research workers, and people to be cogs in the ever growing bureaucracy and administration and for the professional ranks.

Our training, far from being a luxury bestowed upon a lucky few, is essential. It is essential both to the society as a whole and specifically to the capitalist class who depend upon it for the extraction of maximum profit. Their economic need for our skill is the root of our power in the class struggle. Yet it must not be forgotten that capitalism is in crisis, and as the crisis deepens, the ruling class is being forced to jettison even the essentials in its attempt to stay a float. They are faced with the contradiction that they cannot do without us yet cannot afford to keep us. We must analysis this contradiction in every particular instance in order to assess the best demands and tactics. The ruling class alone would like to see this notion of “privilege” have continued existence, for it has been their strategy towards the developing struggle always to malign students as living off the taxpayers’ money. They foster illusions that higher education is dispensible, an unnecessary luxury which returns nothing to the society which is paying for it. They want if they can to have students in isolation and are preparing the ground for cutbacks and the running down of even the most indispensible parts of higher education. The myth of “privilege” is to them a most useful ally.

However the fact is that education is a right, not a privilege, and with regard to, the finance of it the capitalist class with ’its capitalist state gives us nothing. Furthermore, if the iniquitous suggestions for giving us loans instead of grants became reality we would be reduced to the position of serfs! At a time when more students are quite quickly realising the truth of their position, as future wage earners in educational training our job is not to lag or obstruct such a development but to lead and develop it further.

The “privileged student” idea must be got rid of as the hindrance to struggle that it is. Ultimately it becomes a handy rationale for inactivity, a useful excuse for not getting involved with political work with the mass – “they’re middle class and’ privileged, they’re apathetic” – as well as being a stock superficial analysis when things fail and go wrong.

But students are fighting, and realising that the way out of the individual endeavour to make ends meet on a student grant, is collective struggle to improve their conditions. The economics of student life show that we can be as determined and enthusiastic in struggle as any other section.

Out of the attacks on the education and living standards of students has come a growing understanding of our true class position. More and more students are acting as would any other section of the working class, and now beginning to do so with a higher degree of consciousness. The necessity to fight or be pushed down is being learnt.

Capitalism is attacking our standard of living and the mass of students have maintained a protracted fight to restore the value of their grant. Capitalism is attacking education, cutting back building and teaching, and the quality of the education that we receive is dropping. In the early 1970s it was envisaged that student numbers would reach 375,600, 180,000 and 110,000 in universities, polytechnics and colleges of education respectively by the end of the decade. By 1974 it was expected that there would be 325,000,140, 000 and 60,000 and that these figures would drop further. All over the country research projects, computer centre library extensions etc. are being axed or temporarily postponed. Staff student ratios are worsening and teaching vacancies left unfilled. It is in effect selling the future to save itself today. The threat of the corporate state – fascism imposed by either Labour or Tory – is growing and students are as threatened as any other section.

Students have an essential role to play; our job is to develop the change and ferment that is spreading through our ranks, till the memory of our 1926 General Strike role is but an unrepeatable memory of our infant beginnings. Students should welcome that they are part of the working class, the force for revolution, which in Britain has had a long experience of struggle. By learning from this experience and supplementing it, building it among our own section, we shall make an incalculable contribution to the movement towards revolution.

Not only are students apprentices in the sense that they are getting a training for the job they will do when they leave college; it is only recently that students have entered the arena of class politics, and they are still only apprentices in the strategy and tactics of class warfare. Given that there is such a rapid turnover in the student population, and that for many students their studies only occupy one half of the year, there is a need for us to take this aspect of our apprenticeship seriously, for there are no past masters around to guide us.

Learning how to conduct the struggle has been long and hard, but there is nothing like practice to teach us to distinguish true from false in politics. Over the years the broad masses of students have demonstrated their ability to learn and develop; correct lines have been taken up and diversionary ones which were incorrect have been swept aside.

In the early years of student history, many students were concerned with anti-imperialist issues, especially the war in Vietnam. But some, misunderstanding the nature of real class politics, used this very genuine internationalist aspiration to declare that students were the “revolutionary vanguard” because they were interested in these “political” problems, while workers were still fighting merely “economic” battles. Having no understanding of the situation and the fighting history of the British working class, they tried to use people’s interest in such struggles abroad to dismiss those at home as being reformist and economic. However, this was a sign of the infancy of student politics, and the mass of students quickly moved away from this erroneous idea. It soon became clear that the best way students could genuinely support such struggles was by fighting the same enemy at home, where they could actually have an effect. For students to have gone through the purely “anti-imperialist” stage in their political development is no shame. What was inexcusable, however, was the refusal of the doctrinaire “leftists” to advance beyond this immature stage. As the mass of students advanced, the “leftists” became isolated and they retreated into “revolutionary socialist” student organisations to debate each with one another, which seemed to be an easier option. And others went to the factories to teach the workers politics, and became offended when they were told where to go.

One lesson which some had failed to learn was that adequate attention should be paid to academic work for to neglect this is to risk expulsion or failure, hence demoralisation.

Students now clearly understood that they were not a revolutionary vanguard of any sort, but what was their part in the class struggle? The next diversion came from those who suggested that students were not really being exploited, and had no economic power to fight with in the class war, the best they could do was to stand on the sidelines of workers’ battles, manning the pickets and strike cheering. But this line could not last long. The level of the students’ grant was dropping steadily and in 1971 the DES launched an all-out attack on student unions.

Now students were forced to fight to defend themselves, and it is this that marked the entry of students into real class politics. The original student unions had no autonomy. The college authorities held final control over all finances and constitutions. A union was even hampered in its attempts to organise socials for its members, let alone a campaign for higher grants. So over a period of years, college by college, the unions had won themselves measures of autonomy. The government, taking fright at this development, attacked by circulating a set of proposals, outlining how the power of student unions might be curbed. This was a consultative document but it never reached its first objective for, up and down the country, students, far from consulting with anybody on the subject of autonomy, rather demonstrated that they had it by organising sit-ins, lecture boycotts and demonstrations.

As students fight over these issues, the claims of those who said that students could only play a supporting role in the class struggle were increasingly being rejected. It is becoming obvious that capitalism is at the root of all human problems and that exploitation is not something only found in manufacturing industries. Capitalism will take any human skill and try to make a profit out of it, as any hospital worker or artist will tell you. Students are coming to understand that they are going to have to fight the capitalist system of education if they are to defend themselves, and also that they have the strength to do so.

More recently a new variant of these diversions has been heard. No one nowadays doubts that students have a right to a higher grant, for example, and that they will have to fight to get it, but they argue that others are much worse off than we are. It is right that we should feel concern for the casualties of capitalism, the old and the homeless, but if this concern turns into guilt and inhibit us from taking action over such issues as grants, then we are letting the capitalist class get away with even more exploitation than before. All reformists from the Federation of Conservative Students to the ultra left have attempted to divert the struggle by using this inhibition. The Conservative students argued that because old age pensioners need money more than we do, we should not fight for ourselves. But students have seen through this argument and know full well that the money saved by the exchequer through not increasing grants would not find its way into the pockets of old age pensioners.

During the grants campaign, social democrats of every hue from the Labour Party to the ultra-left put forward an argument of this sort. They pressed for the whole campaign to give priority to students who only receive discretionary awards. But this is a dangerous tendency for several reasons.

First, it is reckless idealism to suggest that students on mandatory awards are better at class struggle than those who are not, and can afford to delay their own demands. Second, when the whole student body has only just begun to take up the fight over its own grievances, it is incorrect to start suggesting that all efforts should be concentrated on one section. The grants campaign is still immature, localised and uneven. Students must be given every support when they decide to take action over a demand they have, not told to give up and go and fight for somebody else.

That is why the slogan put forward by the CPB (ML) demanding a ’Full Grant For All Full-time Students’ was the correct one. It included an end to t he means test, an end to parental contributions, abolition of discretionary awards, an end to discrimination against married women and of course a cash award it summed up the demands of all sections and put forward a slogan which united the whole of the student body. And indeed the mass of the students have shown by their actions that they have taken up this slogan as the correct one for the campaign.

Since then it has become clear that we will never have an adequate grant as long as capitalism remains. The tremendous victory of a 25% increase in the level of the grant in 1974 resulted from hard-fought battles in the colleges, but the battle wasn’t over when the award was announced; the college authorities immediately tried to get as much of it back as possible in increased college charges. Students have coma to see that these authorities are not independent middle-men, but objectively the local agents of the state, whose job it is to implement state education policy. And so the struggle is intensified as the class nature of these bodies is more clearly revealed. Moreover the true nature of the state becomes more apparent as it resorts to destroy individual student unions.

Along with this the tactics have developed. The myth that students have no economic power meant that at first actions were designed as glorious forms of protest. Now students have concrete evidence of their economic power. Demonstrations are no longer the focal point of our campaigns. They have been superceded by such tactics as rent strikes, canteen boycotts, disruption of important research, picketing supplies and occupying buildings vital to the functioning of the colleges, in some cases effective enough to paralyse whole campuses. The social democrats then round on the ordinary students who fail to respond to their time-tabled marching orders and call them apathetic. What slander! Of course every student is very concerned about the level of his or her grant, but this does not mean that they should respond like mindless automatons to the orders of would-be student generals. We are fighting a war, not organising a jamboree.

But some still doubt the student mass. They feel convinced that there is a need for revolutionary change, but they doubt their ability to persuade their fellow students. The days are long past, however, when student activity was restricted to a small band of roving revolutionaries. No section of students has been left untouched by the massive developments of the past three years. From teachers to doctors, undergraduates and postgraduates, there has been growing struggle, even though of course it has not been uniform. No college has been left unaffected.

Where the line of the Party has been applied and these lessons correctly drawn the advances have been tremendous.

The crisis of capitalism in Britain has never been deeper, sharper. In its weakness capitalism turns for salvation to corporatism with the introduction of wage restraints, both Labour and Tory, Industrial Relations Act and the social contract. We workers for our part have resisted these measures; and the AUEW with the Party playing a major and leading role struck a massive blow at the capitalist state, forcing it into humiliating defeat over the attempt at sequestration of AUEW funds by the Industrial Relations Court. In reply the state can only fight harder, more viciously. In education, the crisis is fully revealed. The contradictions cannot by their very nature be solved under capitalism since it is capitalism, the system which reduces everything to the cash nexus, which gives rise to the problems. The only solution is for the working class in Britain to seize power from the bourgeoisie by destroying its state. Then, once the overwhelming majority are fully in control of their own lives, will the problems within education receive proper attention.

But how do you make a revolution? Certainly the day to-day struggle over conditions of work and pay do not automatically lead to revolution; these struggles have been going on in Britain for over 200 years; and we would surely have had a revolution by now if they were sufficient. And 60 years experience of the Labour Party politicking should be enough to convince us that parliamentary roads to socialism are doomed to fail – the capitalist state is strong enough to accommodate the social democratic manoeuvres of the so-called left wing. Revolution will only occur in Brit ain when the working class mobilises in an attack on the whole capitalist class and its state machine.

This is not a task that anyone can hope to achieve overnight. The balance of class forces in Britain at the moment is such that while capital weakens daily and becomes more ferocious, the working class has not yet consciously espoused socialism. The working class is fighting – it has always had to fight for its survival – but that fight is not yet consciously revolutionary.

Only the guerilla struggle line of the Party can develop the mass political consciousness which will lead the way forward to the dictatorship of our class.

Guerilla struggle is class war fought at the stage when all out attack on the bourgeois state machine is not yet possible. It aims to tip the balance of forces in favour of the working class through the development of its struggle and political clarity over a long period of time. It is primarily waged at one’s place of work where capitalist exploitation begins, and it is consciously directed towards extracting the political essence from every situation and learning from it, so destroying illusions about ,reforming capitalism into socialism or solving capitalism’s problems by some form of class compromise. Guerilla struggle is of the mass, not troops automatically obeying generals’ orders, but where the initiative of the rank and file is given play. It actually’ weakens’ the capitalist class when it is fought successfully, and strengthens the morale and fighting spirit of the working class. It is above all an ideological question – class compromise or class struggle, slavery or change through revolution. Guerilla struggle is explicitly aimed at raising the consciousness of the mass wherever that struggle takes place.

Guerilla struggle enables us to exploit the contradictions within our class enemy, particularly the contradiction between individual employers, educational institutions etc and the centralised state of the capitalist class. The state may issue edicts for running down education but these cannot be put into effect smoothly and evenly in all colleges at once. By concentrating our forces in a particular college on one or two issues where we are strong, we can force the college to give way. Repeated up and down the country, using the utmost flexibility and relying on mass initiative, this is the strategy which will allow us to repel the attacks by the, capitalist class on our education.

The CPB (ML) has always said, against “leftists” who argued otherwise, that all action by organised labour for however limited gains is political as well as economic. But in a situation where the employers have more and more to rely on the state in their exploitation of the working class, the political aspect of workers’ action has become more apparent and the social democratic illusions harder to maintain.

By its very nature, there is no blueprint which can be handed out to would-be practitioners. This pamphlet could never be a manual giving advice to students how to wage guerrilla struggle. It is rather like learning to swim – you have to jump in the water.

This is not to advocate spontaneity. Guerilla struggle is the strategy and tactics of this period of the class war, and therefore must be carefully planned, based on a correct appraisal of the situation and on knowledge of the strengths and weaknesses of a particular college and the students in it. To conduct such a war, we have to know our specific conditions, and for everyone of us this can only come through involvement in the struggles of our colleges over a long period of time; and if possible research into its union, history of struggles, finances and research projects. Once college might have a tradition of fighting over one particular issue – union autonomy perhaps – and clarity on this issue will be greater and hence more sure of a solid response. But to automatically expect the same response over academic standards for example would be wrong. There will always be uneven development of political consciousness, and attempts to level it out or to reduce all battles in colleges to the lowest common denominator of consciousness would be disastrous. This demands that those who lead do a great deal of preparation, so that even those who are not active understand the issues and are in support. They will then constitute a strong reserve to be called upon if needed. For struggle to be revolutionary, it must be of the mass and not of the few. If the mass in its organisations is not prepared to fight, we must oppose adventurist decisions to try to increase the level of action. A sit-in by 50 can be mass action if it springs from the level of understanding of the mass- its organisation, its policy and commitment, and if it is tactically sound. Because of this we can learn the true lessons, of class war from it. A sit-in by 250 can be adventurist if it springs from the sleight of hand of a few false leaders or demagogues – tactically unsound, politically elitist, ideologically uncertain with a false target. It can only lead to demoralisation, division and confusion.

Mass struggle demands and creates a special kind of leadership. New class warriors emerge to lead the battles with vigour and tenacity. They may be people who do not regularly attend union meetings, but once a rent-strike begins will throw themselves into organising it, conducting it with ingenuity and humility. Giving full rein in such initiative at the local level can be enhanced by correct national leadership. Truly national leadership knows the mass and its situation so well that it can guide and foster struggle, not by straitjacketing the mass but by taking the ideas of the mass, refining, concentrating them and returning them to provide new impetus and insight for mass struggle.

When we know our own particular situation well, we need not be afraid to take a positive lead. On the basis of this knowledge we should attempt to formulate a demand or a call which unites, which wins maximum support where there is maximum clarity; a clear issue (threatened rise in canteen prices) and a clear objective (no rise in canteen prices). Then in the course of the struggle we must abstract from the details of battle those aspects which are of a fundamental class nature.

When there is an issue affecting more than one college, we should not wait until the situation is ripe in all colleges. One college which has been particularly successful can be an encouragement, an example, for other colleges to learn from and apply. National campaigns cannot be built by decree or wait and see attitudes.

There is no shortage of tactics available. Universities with large campus residences might fight with rent strikes, and other colleges with continual harassment of lightning occupations or canteen boycotts. Only those involved at that place will be able to, use everyone’s thinking, initiative to devise the correct tactics. Our choice should be governed by the golden rule, causing maximum hurt to the enemy with minimal risk to ourselves. If a struggle ends up with isolation and successful victimisation of leaders, then it has been a failure, for victimisation can always be avoided if the mass of students are actively involved. There is little gain in political consciousness if the students see the college as powerful enough to kick somebody out, and it usually has the effect of dampening down student activity in subsequent year. We retreat when we are in danger of defeat. In living to fight another day, retreat from the main objective is not an admittance of defeat, just a matter of tactics.

Keep the initiative firmly in t he student camp. We have to learn to be one step ahead of the authorities, anticipating their next move and countering it before they make it. They might try to take the wind out of the campaign by benevolent smiles of “support”, (the Vice-Chancellors calling for higher grants but condemning the campaign), or they might react with threats and intimidation. We must know which, they will do and be able to distinguish bluffs from real threats.

We attack where we are strong and the enemy is weak; we are not yet strong enough to defeat the capitalist education system at Whitehall, but we can often win victories against college authorities locally. In the national grants campaign we did not fully achieve our demand for higher grants. Yet locally, the colleges have held down increases in hall fees as a result of student pressure – effectively raising the level of the grant of students in those halls. From these victories comes increased understanding of our own strength and increased morale. Only through waging successful battles, however small, will the truth of our own indispensability for capitalism be brought home.

Now the main lesson for us must be that our perpetual struggle to defend our standards of living and education will amount only to permanent subjection if it is not developed into the fight to destroy capitalism itself. At every stage of struggle students are being forced to face up to questions of what path to take, what tactics to adopt, what their ultimate goal is. We are faced, time and time again, with two different lines, the revolutionary one and the social democratic one. Suppose there was a rent strike in a college and the Vice-Chancellor or Principal pleads financial hardship, and presents the students with the choice of “ruining the college” or stopping the rent strike. Is the understanding of the strategy behind the rent strike sufficiently clear in everybody’s minds that they understand that it is only when they really threaten the college financially that they are likely to have any effect? Does everyone clearly see the college authorities as the enemy, or do some still see the Principal as an independent force mediating between the students and the state? Do some people secretly hope that: the press will give the rent strike a sympathetic write-up? Do others hope that the NUS executive will do the, job for them, and that the local union executive is to blame when things go wrong? How many doubts and questions are revealed once struggle begins!

Most importantly, the reason why our Party, the CPB (ML) advocates guerilla struggle is because we know that the situation is not static. British capitalism is moving into its deepest crisis ever, and is having to resort to increasingly repressive measures as the working class fights back. The working class needs a strategy which both defends the class in a practical way against these onslaughts while preparing for the revolutionary battles to come. The task is an urgent one. The Social democrats have a revamped war-cry – “the social contract” – with which they try to lull the class into a false sense of security. What contract can we have with capitalism which exists by exploiting us?

Guerilla struggle is the first, part of the strategy of protracted war; no one rent strike can hold college charges down for ever, and no one occupation will forever stay off the threat of victimisation. The realisation of this is growing among students, and the task before us is to transform this realisation into an understanding that ultimately the working class ids going to have to come to grips with the question of state power. We must convince students that only by smashing the bourgeois state and building a state of the proletariat that the long-term future of education in this country will be secured.

The leadership of the mass must be conscious of its revolutionary aim. Only those whose sights are set on winning the long-term war will have the tactical sense to withdraw in order to prepare better for the next battle. Conducting guerilla struggle is hard work, as we have seen, and requires much preparation. The revolutionary can see that the only real gains come through increased mass consciousness and has that as his goal; the trade unionist who sees no further than the immediate battles may be tempted into opportunism; he may see no reason why he should not retreat behind the closed doors of committee politics so long as he delivers the goods in the end. Destroying the state power of the bourgeoisie is a long and arduous task, and requires conscious political leadership – it cannot be left to chance or a notion of spontaneous working class action.

Such a leadership cannot be imposed on an unwilling class from the outside. It must be a development from that class, and a lasting development through these leaders being recruited to the Party of the working class, the CPB (ML).

Parliamentary forms of politics are obsolete, and the capitalist state could readily dispense with Parliament altogether if it ever proved troublesome. Guerilla struggle, for all sections of the working class, is the only strategy possible at this point in time. Only when Party and class, leaders and mass are fully part of one another can revolution happen in this country.

Britain has the oldest and most experienced proletariat in the world. When that proletariat flexes its muscles, capital quakes. When it decides to strike, the bourgeois state machine will be dealt its death blow. Students have a vital and important part to play in bringing this about, and it is their honour and duty to cake sure that they do not shrink from the task.