Graph 1: LEVELS OF INEQUALITY IN EDUCATION

ISJ 2 Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From International Socialism 2:90, Spring 2001.

Copyright © International Socialism.

Copied with thanks from the International Socialism Archive.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

The landslide election of Tony Blair’s Labour government in May 1997 raised expectations that there would be changes after the miserable and miserly Tory years. Officially the government spoke of the need for restraint and following Tory spending plans – but it also bombarded us with Things Can Only Get Better, and many, up and down the country, believed it. With a huge majority of 175 and government financial surplus in the bank, it clearly could have reversed many of the cuts and privatisations of the Tory years. The approaching general election gives us the opportunity to look at New Labour’s record and ask a simple question – has it made things better?

What follows is not a complete review of every area of government social and public policy. Instead we focus on five representative areas where New Labour promised to be different from its Tory predecessor – dealing with poverty and inequality, taxation policy, race and asylum policy, crime and civil liberties, and finally education provision.

On coming to office in May 1997 Blair’s government inherited a country more unequal than at any time since the end of World War Two. During the 18 years of Tory rule Britain had become one of the most unequal countries in the West. [2] The election of Thatcher in 1979 marked the reversal of a trend towards greater equality that had characterised much of the post-1945 period. [3] In its place there was – as a deliberate political objective – an increasing divide between rich and poor. A brief glimpse of the poverty landscape in 1997 makes for grim reading. In 1996–1997 almost one quarter of the population were living on incomes below 50 percent of the national average, while one in three children were being brought up in poverty. Between 1979 and 1993–1994 the bottom tenth of the population saw their incomes fall by 13 percent, while the richest tenth saw their incomes increase by a staggering 65 percent over the same period. [4]

The reasons for this, while varied, are not too difficult to identify. One of the major contributing factors was the massive increase in unemployment during the period from the mid-1970s through to the 1990s. Rising unemployment not only forced many millions of workers and their families to seek state benefits, it also acted as a downward pressure on the wages of those in employment. A key factor, then, in helping to explain the rise in poverty under the Tories was the rapid growth in the working poor.

In a climate of rising demand for benefits of one kind or another, however, the Tories sought to punish the poor. Ideological attacks on ‘welfare scroungers’ and the so-called ‘dependency culture’ were backed up by policies which sought to reduce not only the real levels of benefits, but also further limit entitlements to state support. As recompense for their increasing poverty and hardship the poor would be increasingly policed by a range of state agencies in an effort to drive them into poorly paid employment.

Importantly, the Tories made great efforts to legitimise their policies by attacking the idea of ‘dependency’ itself. Largely borrowed from the US policy-making and academic communities, the idea of state or welfare dependency was centred upon the notion of an ‘underclass’. [5] Popularised by right wing US academic Charles Murray, the notion of an underclass suggested not only that welfare dependency was undermining the work ethic, but the concept also condensed all the pet hates of right wing conservatism – ‘family breakdown’, increasing ‘illegitimacy’ and ‘moral breakdown’, crime, ‘delinquency’, and general ‘disorder’ in all its forms.

During the 1980s and 1990s the Tories had made great play of their goal of reforming the welfare state. New Labour was to pick up this particular thread and run with it in ways that both diverged in some respects with the Tory reforms but also embraced key elements of Tory thinking. In Labour’s green paper on welfare reform in 1998, for example, one of the key rationales for reform was to reduce welfare expenditure, with the Thatcher and Major governments attacked for having failed not only to reduce public expenditure in this respect but also for presiding over a massive increase in social security spending. [6] New Labour also expressed a number of those other ‘concerns’ long beloved of the Tories, notably over crime, rising divorce rates and family ‘breakdown’. Here the rise in lone-parent families during the 1980s and 1990s was highlighted as a particular factor contributing to the continuing prevalence of poverty.

In arguing for the ‘reform’, or in their preferred term ‘modernisation’, of welfare, Blair and other leading Labour politicians were at pains to stress that this would not mean a return to the ‘tax and spend’ policies of ‘Old Labour’. In place of both this and the Tories’ market-based policies, a new ‘Third Way’ would be developed. [7] Since this notion was first mooted there has been considerable debate as to its meaning. What is clear is that it represents both a departure from the commitment of past Labour governments to redistribution and a greater degree of material equality, and an embracing of the market. This is couched in terms of another favourite slogan beloved of Thatcher, that ‘there is no alternative’.

For New Labour there is ‘no alternative’ because we now live in an era of ‘globalisation’. [8] For New Labour globalisation means that it is both impossible and undesirable for the government to control multinational capital – any restrictions on their activities will merely chase them away to another location. The only way for Britain to prosper is through the development of a ‘strong’ economy, characterised by low taxation and flexible labour markets. Through this, it is claimed, employment will be created, opportunity enhanced, and poverty reduced.

This emphasis on paid employment represents a key aspect of Labour’s approach to poverty. Work, defined as paid employment, is held up as the source of salvation for those who find themselves ‘socially excluded’. Thus for single parents or those with disabilities improved welfare benefits are not the answer – but work, any work, is. As ex social security secretary Harriet Harman put it on taking up office in May 1997, ‘The best form of welfare for people of working age is wor.k’ [9]

The launch of the ‘New Deal’ for employment, or ‘Welfare to Work’, built upon the Tories’ Jobseeker’s Allowance introduced in 1996. But there was another influence on Labour’s thinking at this time – the ‘workfare’ policies being pursued by Clinton and the Democrats in the US. Key to both Labour and Clinton’s policies were attacks on what were termed the ‘workshy’. Thus Harriet Harman and other Labour ministers attacked not only single parents, but also ‘squeegee merchants’, ‘beggars’, and increasingly, refugees and ‘illegal immigrants’. As part of this process they were diverting attention away from the real causes of poverty: miserly benefits, ‘poor work’ and a system geared to enriching the minority at the expense of the majority – the poor get poorer because the rich get richer.

Welfare to Work represents one of the key policies introduced by Labour to address the problems of poverty – there have been many others. What stands out from these is the shift in key aspects of the language being used by New Labour. Important here is the notion of ‘social exclusion’. The establishment of a Social Exclusion Unit in Westminster in 1997, and the declared objective of the Scottish Parliament to achieving greater ‘social inclusion’, reflect the gradual but significant replacement of the notion of poverty under New Labour. While the government has made several statements announcing its commitment to tackling poverty, the issue of poverty as such has slipped off its agenda. ‘Social exclusion’, while open to differing definitions, is almost wholly defined by Labour as exclusion from paid work. Inclusion, in turn, results from paid employment. That low wages may contribute to the continuing poverty of the poor is largely sidetracked.

New Labour has made much of its commitment to greater ‘social justice’ and achieving ‘equality’, albeit defined in terms of equality of opportunity, not outcome. [10]

The government has made a number of commitments to abolish child poverty within 20 years, and has introduced several policies widely seen as progressive including the national minimum wage – albeit at a very low level – and a series of tax credits for low income groups. But in terms of tackling inequality Labour has done little to reverse the growing social polarisation that was such a pronounced feature of Britain under the Tories. During the first two years of Labour rule the widening gap between rich and poor pushed another 500,000 people into poverty. Thus roughly at the midway point of the life of the first Blair government over 14 million people (including over 4 million children) live in poverty (defined as less than half average income). This is more than double the number of the early 1980s. Department of Social Security figures published in July 2000 showed that the proportion of the population living on less than half the average income rose from 16.9 percent to 17.7 percent between 1997 and 1999. [11]

While Labour has argued that it will take time to tackle poverty, the rich continue to prosper. A breakdown of the government’s own figures shows that the incomes of the richest have been rising faster under Labour than under the Tories. The richest 10 percent of the population saw their incomes rise by 7.1 percent during the first two years of Labour rule, compared with 4.3 percent under the final two years of the Tories. The poorest 10 percent, by contrast, saw their incomes rise by a meagre 1.9 percent.

One of the key election battlefields between Labour and the Tories will undoubtedly be over taxation. Each of the main parties will no doubt claim that tax cuts are in the offing, and that by voting for them people will have more of their income at their disposal and hence greater freedom, or choice over what to spend their money on.

Expressing the debate in these terms emphasises the extent to which both parties have bought into a wider neo-liberal agenda – consumers know best, market mechanisms are the best form of provision of goods and services, state provision is inefficient and bureaucratic, the state should have a minimal role in social provision.

But what neither party will talk about is the way in which changes in taxation over the last 20 years have increased inequality. Taxation is a complex area, but we will deal with changes in three areas – direct personal taxation (income tax), National Insurance payments, and VAT. The changes in these three areas since 1979 have been quite astonishing.

When the Tories were elected in 1979 personal direct taxation was levied at a basic rate of 33 percent with earnings-related increases to a maximum top rate of 98 percent (on unearned income) and 83 percent (on earnings). By 2000 the basic rate was down to 22 percent (with a low start 10 percent tax rate on the first £1,520 of taxable income), while the top rate had been reduced to a mere 40 percent.

There are a couple of points to emphasise about these figures. First, everyone starts at the 10 percent tax rate, even the richest. Second, the top rate of 40 percent actually starts at quite a low level, on taxable earnings over £28,400 (or earnings just over £32,000 [12]) – this rate of tax will be applied at the same level to those earning £33,000 as to those earning £1 million a year or more. In 1979 approximately 3 percent of the population were paying the top tax rate (83 percent). In the year 2000 some 10 percent of the population were paying the 40 percent levy. These changes to personal taxation have been introduced gradually since 1979, as table 1 shows.

|

Table 1: INCOME TAX RATES ON EARNED INCOME, 1978–2001 [13] |

|||

|

Fiscal year |

Lower rate (%) |

Basic rate (%) |

Higher rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1978–1979 |

25 |

33 |

40–83 |

|

1979–1980 |

25 |

30 |

40–60 |

|

1980–81 to 1985–86 |

– |

30 |

40–60 |

|

1986–1987 |

– |

29 |

40–60 |

|

1987–1988 |

– |

27 |

40–60 |

|

1988–89 to 1991–92 |

– |

25 |

40 |

|

1992–93 to 1995–96 |

20 |

25 |

40 |

|

1996–1997 |

20 |

24 |

40 |

|

1997–98 to 1998–99 |

20 |

23 |

40 |

|

1999–2000 |

10 |

23 |

40 |

|

2000–2001 |

10 |

22 |

40 |

The astonishing point to take from table 1 is that the top tax rate under New Labour has remained lower than it was during the whole of the first two Thatcher administrations!

New Labour has argued that the low start rate is an effective means of dealing with poverty, yet unemployment and low pay (two major causes of poverty) mean that approximately one third of the adult population in Britain do not earn enough to even pay tax. In these circumstances low start tax rates are an ineffective means of combating poverty.

National Insurance (NI) has its roots in the Liberal welfare reforms of 1911. From that time it has been portrayed as an insurance payment, not a tax, made up of contributions from employers, state and employees. It is in reality simply another form of taxation. There is no connection between what workers pay in NI contributions and the levels of benefits they receive. Once again changes to NI rates have benefited the rich and employers. In 1979 the basic rate payment was 6.5 percent of earnings. This has grown to 10 percent in 2000. The employers’ contribution has declined over the same period from 13.5 percent to 12.2 percent. Once again the tax is banked heavily in favour of the rich. There are both lower and upper payment thresholds which mean that an individual has to earn over £76 per week to pay contributions (the lower limit) and payments stop on any earnings over £535 per week. Employers only start paying their contributions when their employees earn over £84 per week. One of the more unsavoury consequences, according to the Institute of Fiscal Studies, is that this has produced ‘labour market bunching’ – in other words it encourages employers to pay workers below the £84 per week employer entry level. [14]

Finally, the most dramatic shift in the tax burden since 1979 has been the growth of indirect taxation. In 1979 the standard rate of VAT was 8 percent. It now stands at 17.5 percent. The argument from both New Labour and the Tories is that this increases incentives to work. Yet there is something illogical about this claim – if a high direct tax discourages people from working because they can not afford to buy goods, why will reducing direct taxation (and giving people slightly more disposable income) encourage them if they still can not afford to buy goods which are subject to high indirect taxation? The answer, of course, is that the change from direct to indirect taxation has meant that for the rich the tax burden is reduced while for the poor it is increased. The old adage that to encourage the rich we give them more money, to encourage the poor we give them less, seems to fit perfectly.

Since Labour’s election in 1997 two sets of events have dominated the struggle against racism in Britain – the continuing fallout from the publication in February 1999 of Sir William Macpherson’s report into the death of the black teenager Stephen Lawrence, and the unfolding implementation of the 1999 Immigration and Asylum Act. Before Labour’s landslide in 1997 anti-racism had been one of the factors fuelling the deep opposition to John Major’s Tory government. For most of those who had fought against racism in numerous campaigns it seemed inconceivable that Labour – even New Labour – would fail to be an improvement on the Tories.

In the event, the first phase of Labour’s rule seemed to bring a welcome change. By agreeing to set up the Macpherson inquiry, home secretary Jack Straw appeared to be breaking with the past. Of course it was the years of hard campaigning by the Lawrences and their supporters which was the motor force, but the Macpherson inquiry finally revealed to very wide layers of white people the level of racist violence in Britain and the complicity of the police. Moreover, unlike the last major government inquiry into racism in Britain, the Scarman report which followed the 1981 riots, Macpherson finally accepted that ‘institutional racism’ existed in the police, the criminal justice system and elsewhere. This earned him the enmity of the right. The Daily Telegraph in particular has fought a rearguard action to roll back the findings of Macpherson by painting it as the cause of a crisis in police morale and a rise in crime. These claims were taken up by William Hague at the end of 2000. [15]

Yet two years on from the publication of the Macpherson report the sense has grown that any change has been cosmetic. ‘Institutional racism’ is in danger of becoming a required phrase, emptied of real content. As the Campaign Against Racism and Fascism (CARF) noted, ‘Those agencies which assert that they are concerned about tackling institutional racism are not examining racism in new ways to find radical cures but merely resorting to old-style palliatives (reminiscent of 20 years of equal opportunities programmes), increasing ethnic recruitment of staff and providing more culturally-appropriate service delivery.’ [16]

In practice, the police and criminal justice system still do not take racist violence seriously. Witness the failure, twice, of the police and Crown prosecutors to convict the murderers of Surjit Singh Chhokar in Wishaw, Lanarkshire. [17] Racism remains rife in the Metropolitan Police, according to an internal report by Sir Herman Ouseley, former chairman of the Commission for Racial Equality. [18] Even worse, the police are still killing black people and getting away with it. In January 1999 Roger Sylvester died after being ‘restrained’ by police. In December 2000 the Crown Prosecution Service claimed there was insufficient evidence to charge anyone. [19] These deaths are the extreme end of a systematic racism which leads to black people being five to six times, and in places 7.5 times, more likely than whites to be stopped and searched by police. [20]

It is also the case that Labour’s authoritarianism continually cuts across any subjective commitment to anti-racism. For example, its plan to remove the right to opt for jury trial rather than trial by magistrate for certain offences will affect black defendants disproportionately, taking away a measure of protection against racism. Likewise, Labour’s contempt for freedom of information and its determination to entrench secrecy compounds the police’s lack of acountability and contradicts Macpherson’s call for openness and disclosure.

The other major area highlighted by Macpherson was education. Recent research has confirmed the institutional racism which exists in education, often despite the best efforts of anti-racist teachers: ‘Available evidence suggests that the inequalities of attainment for African-Caribbean pupils become progressively greater as they move through the school system ... Black pupils are often treated more harshly [in disciplinary terms].’ [21]

Yet Labour is committed to competition, streaming and league tables in education, and refuses to tackle the exclusions which are a product of such competition and which disproportionately affect black pupils. (The exclusion of black pupils runs at five times that of whites. [22]) Anti-racist teachers have been left to use whatever space may exist in the new citizenship lessons without any government support in the form of a strong anti-racist component in the national curriculum, nor any programme to tackle black exclusions.

Even for those who succeed – in the sense of gaining educational qualifications – discrimination in the labour market is not reduced. In fact, men and women from minority ethnic communities with higher educational qualifications are two to three times more likely to be unemployed than their white counterparts – a higher rate of disadvantage than among those with no qualifications! [23] This alone should be enough to prove that Labour’s obsession with training and education (without regard to the temporary and low paid nature of many of the jobs available) will never in itself deal with the systematic racist discrimination in employment which still exists at all levels.

Thus neither in its education nor its employment policies does Labour seriously deal with continued institutional racism. In policing and criminal justice, its commitment to a powerful state far outweighs any concern about racism.

It is on the issues of asylum and immigration, however, that Labour’s record has been truly shameful. While decrying institutional racism in words, it has been busily entrenching it in deeds. As Imran Khan, solicitor to the Lawrence family, argued, ‘There is hypocrisy at the heart of this government. They are trying to promote anti-racism by using the Lawrences but they are also undermining it completely by bringing out racist asylum and immigration legislation.’ [24]

The 1999 Immigration and Asylum Act was explicitly premised on an acceptance of the fallacy that it was cash benefits which attracted economic migrants to the UK: ‘... experience has shown that [provision in kind] is less attractive and provides less of a financial inducement for those who would be drawn by a cash scheme’. [25] Just like the Tories and the gutter press, Labour ministers have twisted the phrase ‘economic migrant’ from its original meaning of ‘labour migrant’ into a synonym for ‘international benefit scrounger’. Having adopted this kind of logic, no wonder the government was prepared to pick and mix the worst aspects of other European Union states’ asylum policies. As CARF put it, ‘Most European countries now have an asylum reception system involving a degree of compulsion, or a voucher system. Britain has gone for both, for about the harshest possible option for those who need support.’ [26] Labour’s asylum policy has generalised the worst practices found across the EU and the worst aspects of the existing asylum system developed by the Tories. The policy has three main aspects. [27]

Increased deportation and detention: Under Labour the Oakington ‘reception centre’ near Cambridge has been opened, Aldington prison near Ashford has been turned into a special detention centre, and one wing of South Yorkshire’s Lindholme prison has become a detention centre. These are in addition to the existing centres at Campsfield House near Oxford and Harmondsworth near Heathrow airport. Around 1,000 asylum seekers are incarcerated in detention centres and ordinary prisons at any one time.

Labour’s record on deportations is actually worse than the Tories’. In 1997 three people an hour were kicked out of Britain. By the end of 2000 Labour was kicking out five people an hour from Britain. Between May 1997 and October 2000 Labour deported 24,103 people. If account is taken of those who are administratively ‘removed’, the figure was an astonishing 131,378 people. Not only is this harsher than under the Tories, the rate is accelerating. Home Office figures showed that for the first nine months of 2000 there was a 25 percent increase in the number of deportations and removals over the same period in 1999. [28]

Introduction of vouchers: Voucher schemes for asylum seekers were pioneered by local authorities after the Tories’ 1996 Asylum Act. Councils acquired the responsibility for supporting asylum seekers who made their claim ‘in country’, but were only allowed to provide support ‘in kind’ to adults without children. Labour decided to generalise this principle of cashless support to all new asylum seekers, whether single adults or families. Moreover the value of the vouchers, of which only £10 can be exchanged for cash, was set at only 70 percent of Income Support. Such is Labour’s infatuation with the private sector that the voucher scheme’s operation was awarded to a multinational company, Sodexho. In its attempt to encourage retailers and supermarkets to sign up to the scheme Sodexho boasted that the government was letting shops pocket the change, or as they put it, offering ‘a revenue-raising opportunity’.

The voucher scheme has received more publicity and caused more revulsion than any other aspect of Labour’s brutal new asylum system. Its deliberate stigmatisation of asylum seekers is an open invitation to racist discrimination against them. Transport and General Workers Union general secretary Bill Morris argued that Home Office policies on asylum had ‘given life to the racists’, and called for the scrapping of the ‘degrading and inhuman’ asylum voucher scheme. [29] This demand was taken up by the TUC and threatened to win the support of delegates at Labour’s 2000 annual conference. In order to avoid losing the vote, Labour’s leadership promised a ‘comprehensive review of the asylum support system’. The government’s betrayal was swift. By November it transpired that the ‘comprehensive review’ was to be an ‘operational’ not a ‘policy’ review, carried out by immigration minister Barbara Roche, with a clear preference to simply provide vouchers in smaller denominations. Morris declared himself ‘utterly disillusioned’ but insisted that ‘vouchers are an affront to human dignity on which my union will not compromise’. [30]

Forced dispersal: From 2000 asylum seekers became the responsibility of a punitive and chaotic new agency within the Home Office, the National Asylum Support Service. Asylum seekers are now forcibly dispersed to areas outside of London, regardless of any family, friends or specialist support which is more often available to them in the capital. If they refuse to go they are deemed to have forfeited any right to accommodation. Again, dispersal was a practice pioneered by local councils in London and the south east of England after the 1996 Asylum Act, a practice which Labour has now generalised to almost all asylum seekers.

In theory, the Home Office planned to send people to ‘cluster zones’ which were ‘multi-ethnic’ (thus supposedly reducing the likelihood of racist attack) and could provide services for particular nationalities and languages. In practice, dispersal has been to the poorest areas with high levels of empty housing stock. In its cynical disregard for the wellbeing of asylum seekers, the Home Office has commissioned accommodation from private landlords at rock-bottom prices. The Home Office has also driven down the price it is prepared to pay to the regional consortia of local authorities, which are organising the reception of dispersed asylum seekers. Indeed, the South West Consortium reported an admission by Barbara Roche that ‘price is the main driver in arranging accommodation for asylum seekers’. [31] So all the talk of ‘cluster zones’ and ‘multi-ethnic communities’ was diversionary window dressing for the dumping of vulnerable people, often without any support whatsoever. No wonder there is evidence of many people refusing to be dispersed at all, and others returning to London, ‘disappearing’ from the authorities if they have to. [32]

Instead of restoring asylum seekers’ right to claim social security benefits and giving them the right to work [33] – which would be right and cheaper – Labour has created a new apartheid social security system separate from and deliberately inferior to the already miserable levels of the welfare state. Dispersal constitutes authoritarian social engineering on a huge scale. It would be difficult to create conditions as likely to promote racist attacks if you tried.

By the end of 2000 a slight shift in Labour’s rhetoric could be detected, with greater emphasis in ministerial speeches on the positive contributions made by immigrants to Britain. In part this may have been because Labour realised that the nakedly reactionary nature of its immigration and asylum policy had left it exposed to criticism from the left and isolated from some of the middle class forces it always seeks to co-opt. [34] In part, it reflected attempts by Britain, in line with other European states, to deal with growing shortages of skilled labour in certain occupations by easing the availability of some work permits. [35] Yet the hypocritical praise of immigrants only appears in obscure publications and specialist forums while in practice the stigmatisation and punishment of asylum seekers continues unabated, ready to be wheeled out during election campaigns to appease racist sentiment.

When the notion of ‘institutional racism’ was first developed by the Black Power movement of the 1960s it was an attempt to capture the way that racism is about more than the ideas or actions of prejudiced individuals. Rather it is structured into society in a much more fundamental and systematic way. As Stokely Carmichael argued, institutional racism ‘originates in the operation of established and respected forces in the society’. [36] By contrast, New Labour is fully committed to actually existing capitalism, and has repudiated even the social democratic aim of using the levers of government to ameliorate poverty and inequality. The market will somehow deliver if only the state sets capital free to work its magic. The last thing Labour wants is to challenge established and respected forces. This means that although language and other surface manifestations may change, there is an inability and an unwillingness to strike at the heart of racist practice.

Much worse, however, is the way that Labour’s commitment to the existing state and to nationalism leads it to maintain one of the main practices underpinning institutional racism and feeding popular racism – immigration controls. Labour claims that its asylum policy is not racist and acts as if it can be segregated from any ‘post-Macpherson’ initiatives to tackle institutional racism. Labour ministers also claim that because, unlike the Tories, their legislation is not motivated by a desire to win electoral advantage by pandering to racism (‘playing the race card’) it cannot be racist. Even if this were true in terms of their subjective motivation, it is the content and consequences of its actions on which government must be judged.

Labour remains wilfully blind to the way that racism already informs and permeates the battery of immigration controls built up since the 1960s. The function of these controls has never been to prevent immigration full stop. What they do is discriminate against particular nationalities – those from the countries outside Western Europe, the US and the ‘old’ white commonwealth – who are overwhelmingly non-white. The justification for exclusion has always been made in racist terms – the immigrant is a scrounger and a job stealer. This is the basis of the culture of suspicion which suffuses the operation of immigration controls, making them racially discriminatory in outcome. This is how the theory of national interest which informs immigration controls inevitably translates into the practice of racial discrimination which constantly threatens to spill over from the current wave of migrants to those already in the country whose ‘race’ marks them out as different.

Thus the political consequence of Labour’s action is – as it was in the 1960s – to open the door to the right. Witness the frenzied campaign against asylum seekers in much of the national press in early 2000, accompanied by Tory talk of being ‘flooded’ by ‘bogus’ asylum seekers in an attempt to recover electorally by using racism. That this atmosphere of racist paranoia can then be picked up on by the Nazis was revealed by British National Party leader Nick Griffin:

The asylum seeker issue has been great for us ... It’s been quite fun to watch government ministers and the Tories play the race card in far cruder terms than we would ever use, but pretend not to. This issue legitimises us. [37]

Fortunately the racist reaction has been matched by a counter-reaction from a hardening anti-racist minority, often led by socialists. Asylum seekers have joined trade unionists on May Day marches and pickets of supermarkets participating in the voucher scheme. Thousands have signed public statements in defence of asylum seekers, including many trade union general secretaries. [38] Churches and charities have begun to campaign over the unequal treatment of refugees by the government. [39] When 58 Chinese people were found suffocated in the back of a lorry at Dover in June 2000, the official reaction was essentially one of callous indifference, but for many people it evoked a basic human sympathy which could begin to undermine the racist caricature of the wily, grasping asylum seeker.

It will be essential to continue these struggles, with particular vigilance required against potential racist campaigns in the areas to which asylum seekers are being dispersed. However, socialists need to go further. It is our job to ensure that anti-racism is integrated into the growing anti-capitalist movement; to expose the hypocrisy and brutality of a globalisation which tears down all barriers to capital while building them up against those who are fleeing persecution or looking for work; and to wage the battle within the working class to ensure that racism and despair are overcome by class consciousness, internationalism and hope for a better world.

During the 11 years in which Margaret Thatcher was prime minister, annual crime rates in Britain more than doubled to over 6 million crimes in England and Wales alone. [40] At the same time the criminal justice system became overloaded with a massive increase in people passing through British courts and prisons. During this same period police detection rates fell, so that currently only around one in every four recorded crimes is ‘cleared up’, in police terminology. This deterioration occurred despite a Treasury expenditure on the criminal justice system which reached over £10 billion annually by the early 1990s. [41] The then Conservative government was highly embarrassed by this seemingly uncontrollable rise in the crime numbers. They had been elected in 1979 on a ‘law and order’ ticket, but by the mid-1980s crime had come to be seen as a normal, everyday experience affecting many people’s lives.

Thatcher’s government was highly criticised and were accused of ‘losing the fight against crime’. Jock Young has written that the police and other crime control agencies across Britain were deeply pessimistic about their chances of reducing crime and that there was a general feeling that ‘nothing works’ in the prevention of crime. [42] This criticism came from all quarters. Remarkably, a 1986 report from the Metropolitan Police attacked the Thatcher government for initiating policies which contributed to the high crime rate, arguing that:

… the government ... pursues an economic policy, which includes a Treasury-driven social policy, that has one goal – the reduction of inflation. Any adverse social byproducts are accepted as necessary casualties in the pursuit of the overall objective. [43]

In this climate of ‘crisis’ Thatcher turned her attention anew to the law and order debate. In keeping with her general philosophy which placed emphasis on individual rather than state responsibility for social problems, the government embraced the idea of ‘community safety’ which held that everyone in a neighbourhood – residents, private businesses and community groups alike – was to be held responsible for reducing crime. This philosophy was designed to turn attention away from the failures of the police and government, and encouraged private and public sector crime prevention partnerships. It also spawned numerous Neighbourhood, Business and Shop Watch schemes to encourage individuals to become the eyes and ears of the police. In 1994 Michael Howard even went so far as to say that patrols of ‘active citizens’ should ‘walk with a purpose’ around their estates in order to deter any potential offenders.

And 1994 was also the year in which a particularly vicious Criminal Justice and Public Order Act was passed. This law criminalised trespass and extended police powers to stop, search and detain those suspected of criminal intentions. Travellers, outdoor ravers and football supporters groups, in particular, saw the act as an attack on their lifestyles and as responsible for criminalising the activities of many young people.

When Labour came to office in 1997 these Conservative law and order policies had had little effect in stemming the increases in recorded crime. Tony Blair famously fought this general election on the law and order slogan of ‘Tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime’. The law and order issue was seen to be a great vote-winner. After all, according to the statistics, more people were being victimised than ever before.

In 1998 the Social Exclusion Unit produced a detailed list of areas of concentrated poverty across Britain. [44] It listed literally hundreds of acutely disadvantaged areas across the length and breadth of the country. The New Labour government could have used this information to make the link between increasing poverty and crime (which the previous Tory governments had vehemently denied), but instead it chose to follow the Tory lead and to hold residents in these areas responsible for countering crime and ‘anti-social behaviour’.

Its first piece of law and order legislation was the Crime and Disorder Act 1998. This went further than the Conservatives had dared. A whole raft of practices, such as anti-social behaviour orders, parenting orders and curfews for children, were put in place which gave the courts powers to regulate the behaviour of individuals. Failure to comply with these orders would mean breaking the law and possible criminalisation of people who had never committed a criminal offence in the first place! Alongside these measures the partnership approach to the prevention of crime was enshrined in law, so that local authority officers must now work closely with the police to fulfil a statutory obligation to prevent crime.

New Labour has continued to place the blame on individuals’ behaviour, rather than challenging a system which spawns crime and which also criminalises increasing numbers of young people. Concerned at the rising cost of crime prevention to the Treasury, the government has sought to cut the costs of the criminal justice system rather than question its practices. To this end, access to Legal Aid has been removed for many cases, and the government is keen to push through legislation which will remove the right to a jury trial for many. In probably the last Queen’s Speech of this government, it has signalled its intention to increase the numbers and range of curfews and behaviour orders, to increase the range of community-based punishments, to tighten up drug testing of suspected offenders, and to continue with its programme to remove the right to jury trial. The civil liberties campaigning group Liberty has criticised the government for putting forward coercive legislation which is in danger of breaching human rights on a number of different levels. [45]

When the government publicly responds to high profile crimes, such as the murder of Damilola Taylor in Peckham, it is to place the blame squarely upon the shoulders of local residents, who it says do not care enough to prevent crime. While it continues to deny the link between economic and social disadvantage and offending, it can offer no solution to the problem of crime. Instead it falls back on the old tricks, placing the blame on the behaviour of a few individuals and denying its own responsibility in perpetuating disadvantage and despair.

The NHS aside, the poor state of Britain’s education system has proved to be one of the key political battlegrounds since the 1997 general election. Blair was elected on a platform that promised to prioritise education. For many millions of working class students, pupils and parents, however, the slogan ‘Education, education, education’ seems little more than a sick joke. [46]

The Conservatives had made education one of their priorities during the 1980s and 1990s. As in other areas of social policy, they were concerned to reverse some of the more progressive aspects of state education that were introduced in the 1960s and 1970s. Notably this included an attack on ‘comprehensiveness’ and on ‘progressivism’ – that is, ideas and ways of teaching that were seen as undermining traditional values and morality. The other key targets of Tory attacks were teachers themselves. The 1988 Education Reform Act represents one of the clearest illustrations of the entire Tory approach to education. Its importance stretches beyond this in that it has set the scene for the policies pursued by New Labour.

The 1988 act placed an emphasis on individual achievement and the individual causes of educational failure. While considerable evidence existed to demonstrate that class background was the major factor contributing to educational achievement, and of the role of poverty in influencing school performance, the Tories largely marginalised this. Instead of addressing such structural inequalities, the Tories were concerned to bolster the fortunes of those groups that were already privileged. The notion of education as a consumer product was to be extended through the provision of parental choice in the selection of schools, with parents also given more influence over schools through the establishment of school boards. That this ‘choice’ was effectively only an option to some middle class parents was ignored.

In addition the 1988 act introduced a wide range of measures that have now become commonplace in the language of education provision – league tables, monitoring and inspection, regular testing and, in England and Wales, the introduction of a national curriculum and the establishment of Ofsted, the schools inspectorate. The 1988 act was founded on the assumption that the key to successful educational provision was control and management, and the rooting out of ‘problem’ or ‘trendy’ teachers. Schools were encouraged to ‘opt out’ of local authority control, with the ‘local management’ of schools favoured. Not surprisingly throughout the period of Tory rule tax breaks and other measures to support and extend the provision of private education were a key weapon in bolstering privilege and elitism. Competition between schools for pupils of a certain standard and background was now the order of the day.

As in other areas, New Labour sought to retain many of the key aspects of Tory policy. Private schools were told that they had little to fear from New Labour, and Gordon Brown has not moved to tax private education. In addition Labour has sought to further extend the marketisation of education introduced by the Tories. Parental choice and the ‘diversification’ of provision – that is, opting out – have been extended. Elsewhere the private sector has been encouraged through the establishment in England of Education Action Zones (EAZs), while the extension of the Private Finance Initiative, now termed Public-Private Partnerships, has allowed private companies greater access to the education sector, opening up schools and colleges to a myriad of profit-making ventures. In addition to building new schools, the private sector increasingly plays a role in the direct running of schools, and of key areas of their educational provision such as information technology. Non-teaching staff suddenly find themselves transferred to the control of private firms, and to all the increased pressures and uncertainties that this brings.

New Labour has sought to comply with and even broaden other areas of Tory policy. Thus the monitoring and inspection of school performance and target setting has been promoted, and Labour has continued to use Ofsted as a weapon to root out ‘defective’ teachers. Like the Tories before it, Labour has also presented teachers and teachers’ unions as the key barriers to its plans to ‘modernise’ education provision. Thus the government is attempting to introduce, in face of mounting opposition, performance-related pay for teachers. Taken together, these developments represent the increasing surveillance and regulation of schools.

For New Labour, the modernisation of the education system is part and parcel of its objective of creating a ‘modern, dynamic economy’, equipping Britain to compete in the new climate of ‘globalisation’. In this respect ‘social exclusion’ is viewed as a waste of potentially valuable ‘human capital’. For Labour, tackling social exclusion in education is primarily about tackling truancy and exclusion from school. Not only are some teachers to blame for this, so are working class parents. Thus, in addition to increasing the regulation of teachers, Labour has sought to increasingly regulate parents. They have to become more ‘responsible’, to be enforced if necessary through various home working and family learning schemes. ‘If only working class parents were more like middle class parents’, appears to be the central philosophy underpinning Labour’s approach in this respect, completely ignoring the fact that it is poverty, poor wages, slum housing and the ‘dumbing down of expectations’ among working class children that are the key factors that affect educational attainment. As in other areas of its political project Labour’s educational policies have a strong moral authoritarian streak. The rhetoric of social inclusion, citizenship and opportunity are frequently couched in terms that focus on individual behaviour, the family and issues of values and morality.

Thus far we have focused on the school system. We would be remiss not to mention other areas of education provision. While some measures have been introduced in both further and higher education to encourage the increasing participation of people from ‘disadvantaged’ backgrounds, in important ways Labour has sought to shift the costs of post-school education onto those less able to pay. The introduction of tuition fees represented a fundamental attack on the principles of free education, and acted as a disincentive to participation in education. While tuition fees have been removed in Scotland after widespread protest, those attending colleges and universities will still eventually have to pay for the costs of their education, with many leaving with huge debts.

The story of Labour’s approach to education is one that has sought at each and every opportunity to increase the opportunities for the free market to penetrate state education and reap vast profits. [47] Teachers’ pay demands have been ignored, and chronic underfunding characterises huge swathes of British education, the small but privileged private sector apart. Despite the rhetoric of social inclusion, meagre funds have been made available for the EAZ programme. Like the Tories, New Labour sidesteps the structural inequalities that continue to be the most significant factors shaping educational performance.

Champagne corks popped in staffrooms across the country in November 2000 at the news that the man who pompously insisted on being called ‘Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Schools’ had resigned. Chris Woodhead spent six years at Ofsted blazing a trail for Tory policies which stifled creativity in the classroom. They imposed a narrow focus upon examination results and performance league tables as the sole yardstick for measuring pupils’ and schools’ achievement. Along the way he stoked up anger amongst teachers by denouncing and blaming them for the supposedly falling standards.

It is ironic therefore that Woodhead’s departure coincided with the publication by Ofsted of an outstanding piece of research looking at educational inequality in schools. The paper, Educational Inequality: Mapping Race, Class and Gender, was written by two highly respected researchers, Dr David Gillborn, head of policy studies at the University of London Institute of Education, and Professor Heidi Safia Mirza, head of race equality studies at Middlesex University. Their research is based upon submissions made to the Department for Education and Employment (DfEE) by schools applying for funds under the Ethnic Minority Achievement Grant (EMAG), a new scheme which replaced Section 11 funding [48] in 1999, and a Youth Cohort Study carried out in England and Wales.

The first point that Gillborn and Mirza acknowledge is that, contrary to Woodhead’s declarations, there has been a general improvement in standards in schools over the past decade. Public examination results should not be regarded as the sole legitimate measurement of educational achievement but, nevertheless, the headline-grabbing reports of improved GCSE and A level results are not illusory. This success is a tribute to the hard work and dedication of teachers in the face of budget cuts and Ofsted’s crude attacks.

The researchers then look at the ethnic group data and suggest:

The most interesting fact to emerge from the EMAG data is that for each of the major ethnic groups we studied there is at least one LEA [Local Education Authority] where that group is the highest attaining. The significance of this finding should not be overlooked, and is a reminder of the variability of attainment and the lack of any necessary preordained ethnic ordering.

In short, the evidence explodes the myth that black pupils are naturally less intelligent than their white peers. Indeed, the report confirms research which indicates that Indian pupils are amongst the highest performing of all the major ethnic groups. This clearly shows that the problems that black children face in schools cannot simply be put down to racism. It also shows that having English as an additional language, as many Indian pupils do, ‘is not an impenetrable barrier to achievement’.

However, having welcomed both the general improvement in standards and the particular success of various groups in different areas, Gillborn and Mirza go on to assert that beneath the surface there are major discrepancies: ‘... there is still a picture of marked inequality elsewhere: there are almost four times as many LEAs where the picture is reversed and white pupils outperform each of the black groups.’

The most recent figures show a slight closing of this gap, but over a ten-year period overall inequality in achievement has widened.

Educational Inequality confirms a widely held belief that many black pupils begin school with a higher baseline level than their white peers. For example, in one large urban LEA with a sizeable African-Caribbean pupil population, children from this ethnic group entered school with baseline levels 20 percent above the average for the area. By the time these children leave primary school, they have already fallen below the average for the authority, and by the time they complete their GCSE examinations, they are 21 percent below the local average. This depressingly steep pattern of decline has also been identified in research carried out in schools in London.

There has been a great deal of speculation about the causes of this trend. David Gillborn and Deborah Youdell provide one of the more interesting and imaginative theories in their book Rationing Education. They identify a phenomenon in schools which they call ‘triage’. The term is borrowed from hospital casualty departments that constantly have to prioritise those patients in need of immediate attention as against those who will comfortably survive and whose case is not therefore urgent, and the hopeless cases who cannot be rescued. Applied to education, triage explains the bitter and divisive competition both within and between schools that was so brilliantly exposed by Nick Davies in a study for The Guardian newspaper which has now been published as The School Report. Schools are under constant pressure to achieve high GCSE grades in order to move up the local league table, and consequently attract more pupils and a greater share of the local resources. Constrained by their limited budgets, they are forced to distinguish between three groups of pupils – the ‘safe’ pupils, those ‘without hope’ and the ‘underachievers’.

The safe pupils can be trusted to do well in their GCSEs and therefore require little attention. Similarly, those without hope can be systematically marginalised or even excluded, as they cannot be relied upon to enhance the school’s position. It is the underachievers, those who, with a little extra coaching, can be lifted up into the higher grades, that schools are forced to concentrate upon. There is, according to Gillborn and Youdell, an ‘A*–C economy’ operating in education. The whole focus of the education system is upon the achievement of the highest grades in those final examinations. The reference to an economy is not accidental. There is a clear and direct link between the education system, the labour market and the needs of business.

Socialists have always argued that under capitalism the principal aims of the education system are to produce the next generation of workers and to inculcate the dominant ideas of society, which are those of the ruling class. However, within those constraints there have been genuine attempts by teachers to establish a comprehensive ethos, which encourages creative and collective learning. Comprehensive education that included a commitment to mixed ability teaching and other progressive elements such as equal opportunities and anti-racism was never fully implemented, but it was sufficiently widespread and potentially dangerous that it required a conscious political offensive to destroy it. Hence prime minister Margaret Thatcher argued in 1987:

In the inner cities where youngsters must have a decent education if they are to have a better future, that opportunity is all too often snatched from them by hard-left education authorities and extremist teachers. Children who need to be able to count and multiply are learning anti-racist mathematics – whatever that is.

Similarly, her successor John Major declared:

I also want a reform of teacher training. Let us return to basic subject teaching, not courses in the theory of education. Primary teachers should teach children to read, not waste their time on the politics of gender, race and class.

Teachers, educational researchers and teacher training colleges were attacked for their apparent obsession with ‘trendy’ issues rather than a commitment to the three ‘R’s of reading, writing and arithmetic.

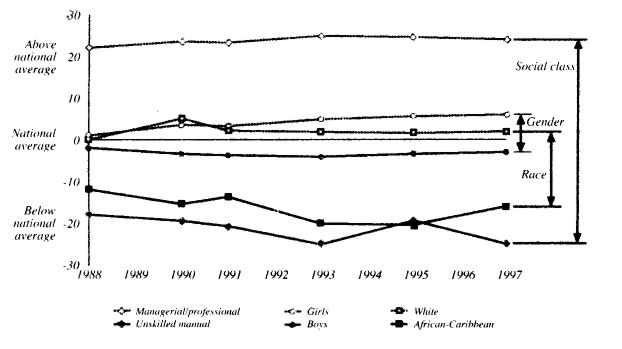

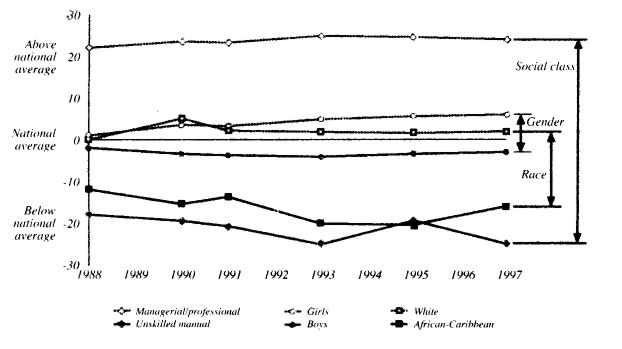

Suddenly, however, there has been something of a revival of concern with these issues. In particular, there has for some time now been a great deal of concern focused upon a so-called ‘gender divide’, with alarm being expressed at the relative decline of boys. Gillborn and Mirza acknowledge that there has been an increase in the gender gap, from 6 percent in 1989 to 10 percent in 1999. However, they go on to argue that:

… the gender gap is considerably smaller than those associated with race and class. In the latest figures, the black/white gap is twice the size of the gender gap. In relation to the national average it is clear that black pupils and their peers from unskilled manual homes experience the greatest disadvantage.

In reality, of course, the various factors that contribute to inequality, whether in education or society generally cannot crudely be separated out from one another. Gillborn and Mirza are right in their assertion that ‘all pupils have a gender, class and ethnic identity – the factors do not operate in isolation’. Nevertheless, whichever way the statistics are examined – whether by race, gender or social class – however crudely defined, it is clear that the children from more privileged backgrounds are more likely to achieve exam success than those from more disadvantaged families. Moreover, the figures show a marked widening of this social class divide.

DfEE figures for 1997 show that children from ‘managerial/professional’ backgrounds are three times more likely to gain five A*–C grade GCSEs than those from ‘unskilled/manual’ backgrounds. In 1988 some 52 percent of children from managerial/professional backgrounds gained five or more higher grade GCSEs; 12 percent of children from unskilled/manual backgrounds reached this benchmark. In 1997 some 69 percent of children from managerial/professional backgrounds achieved five or more higher grade GCSEs, with 20 percent of children from less privileged backgrounds achieving this level.

|

Graph 1: LEVELS OF INEQUALITY IN EDUCATION |

|---|

|

Graph 1 starkly illustrates the extent to which social class is the principal factor in determining educational achievement.

The report does reveal something of the impact of institutional racism in education. Over the ten-year period, as a group, it was only the white pupils who recorded year on year improvements. Pupils from all other major ethnic groups recorded stagnation and decline at various points. Most worryingly, recent evidence suggests that African-Caribbean pupils from ‘non-manual’ homes have been struggling to keep up with children from manual backgrounds in the other major ethnic groups. Overcoming educational inequality will necessarily involve specific initiatives aimed at addressing the problems faced by black pupils. However, this must be part of a wide agenda, which challenges the crude A*–C economy that blights the life chances of millions of young people, black and white.

It was suggested at the beginning of this section that the coincidental publication of Educational Inequality at the time of Woodhead’s resignation was ironic. In actual fact, on receipt of the researchers’ findings, Ofsted initially refused to issue the paper. Rebecca Smithers, The Guardian’s education correspondent, has suggested that Ofsted was bounced into publishing the document only because the Institute of Education embarrassed it by indicating that it would produce the report independently.

It is worth noting the circumstances in which the report was originally commissioned. In the aftermath of the Macpherson report the government established an ‘action plan’. This is something of a misnomer. There have been numerous plans but very little effective action. As part of this plan Ofsted was given ‘lead responsibility’ for promoting race equality in schools. In the wake of this and in the face of bitter criticism from, among others, the Commission for Racial Equality, Ofsted authorised the research, presumably with the expectation that it would back up its own narrow agenda and enable it to carry on business as usual. Woodhead clearly underestimated David Gillborn and Heidi Safia Mirza, and found their conclusions unpalatable. In particular he will have reviled their assertion that social class is the single biggest factor affecting educational achievement.

Woodhead has shuffled off to write for The Daily Telegraph, and there have been rumours that he will become a Tory peer and shadow education secretary. His pretence at lofty independence has finally been exposed. Given his apparent hostility to New Labour, one might wonder why he was not only retained but reappointed by Tony Blair. The truth is that New Labour is committed to the A*–C economy as it fits the government’s wider commitment to serving the needs of big business.

This fixation has been supplemented by a number of ill-conceived schemes such as the EAZs and Fresh Start, which have failed and are being quietly abandoned. EAZs were intended to rejuvenate schools, and to tackle disadvantage and ‘social exclusion’ by clustering groups of primary, secondary and special schools together under the dynamic leadership of firms such as Arthur Andersen, NatWest and Tate & Lyle. Elsewhere it was believed that the reopening of ‘failing’ schools under trendy new names with highly paid ‘super-heads’ would give them a ‘fresh start’ that would lead them to the promised land of exam success. In January 2001 The Times Educational Supplement reported that the EAZ scheme was being dropped, and the Fresh Start initiative has been an unmitigated disaster, with a number of the super-heads having already resigned and examination results achieved which are worse than those posted before the cosmetic transformations. Other initiatives such as the introduction of performance-related pay will add to the competition, destroy the harmony that is essential in effective schools, and add to the inequality which Gillborn and Mirza’s study has exposed.

Finally, many readers will remember Blunkett’s famous ‘read my lips’ declaration, that New Labour would allow no selection in schools by interview or examination. Rather than standing up for this principle, he was forced into an absurd and embarrassing ‘clarification’, which amounted to a pledge to retain this divisive and unfair system.

The comprehensive ideal has now been sacrificed on the altar of big business, to the disgust of Old Labour stalwarts, including many on the right wing such as former deputy leader Roy Hattersley. Challenging inequality will therefore require a dynamic alliance of teachers, pupils, parents and community activists. This coalition of forces will have to struggle against the iniquities of current provision. In addition, however, we must fight for a world in which all talents can freely flourish.

In the run-up to the election of May 1997 socialists rightly argued that Labour was unlikely to deliver significant reforms. But for many working people the experiences of 18 miserable Tory years, the belief that things ‘could only get better’ and certainly could not get worse, and the size of Labour’s majority seemed to hold out the possibility that Labour might just deliver. New Labour has smashed the hopes of May 1997. Its record in government shows it has continued with the agenda put in place by the Tories. It has presided over a government that has increased inequality and poverty, that has criminalised and stigmatised the very poorest amongst the working class, that has proscribed an increasingly vicious, morally authoritarian policy agenda, that has whipped up racism, and that has stood by as education has been privatised and class-based inequalities within that system reinforced. Even in terms of traditional Labour or social democratic concerns, the extent of New Labour’s horrible record is astonishing.

Yet alongside Labour’s woeful record there is increasing evidence that people are looking for something better. This is being expressed via the anti-capitalist movement, the reviving industrial struggles and, electorally, through the Socialist Alliances and Scottish Socialist Party. For the first time since World War Two there is the real prospect of a united, sustained campaign by the far left in a general election. We have got to make the choice clear: a vote for Labour is a vote for continuing inequality, poverty, privatisation and slavish devotion to the market; a vote for the Socialist Alliances and Scottish Socialist Party is a vote to fulfil the hopes that many had in 1997 – to increase spending on welfare, to tax the rich, to stand up to the multinationals and the global economy, to protect the environment and promote workers’ rights. ‘Things can ... get better’ – a vote for the Socialist Alliances and Scottish Socialist Party is a first step to ensuring that they do.

1. This piece was put together to offer an account of New Labour’s record during its first term of government. Different people had responsibility for different sections. Ed Mynott wrote about asylum seekers, Karen Evans about crime and civil liberties, Gerry Mooney and Brian Richardson did two different pieces on education, and Gerry Mooney also did the part on poverty. The other sections and the ‘editing’ were done by Michael Lavalette – whose responsibility it is if it doesn’t hang together.

2. United Nations, Human Development Report 1998 (Oxford 1998). See also J. Seymour, Poverty in Plenty: A Human Development Report for the UK (London 2000).

3. This was a trend. We are not saying that the rich were being expropriated, or class becoming irrelevant, just that the gap between the rich and the poor closed slightly during the post-war boom years.

4. A. Walker and C. Walker (eds.), Britain Divided (London 1997), pp. 22–23.

5. See A. Rogers, Is There A New “Underclass”?, International Socialism 40 (Autumn 1988); and C. Jones and T. Novak, Poverty, Welfare and the Disciplinary State (London 1999).

6. Secretary of State for Social Security and Minister for Welfare Reform, New Ambitions for Our Country: A New Contract for Welfare (London 1998).

7. See M. Lavalette and G. Mooney, New Labour, New Moralism: The Welfare Politics and Ideology of New Labour Under Blair, International Socialism 85 (Autumn 1999).

8. See C. Harman, Globalisation: A Critique of a New Orthodoxy, International Socialism 73 (Winter 1996).

9. Department of Social Security press release, 6 May 1997.

10. See A. Callinicos, Equality (Cambridge 2000), especially ch. 4.

11. Department of Social Security, Households Below Average Income:1994/5–1998/9 (London 2000). See also D. Gordon et al., Poverty and Social Exclusion in Britain (York 2000).

12. The personal allowance for people under 65 is £4,385, thus people start paying the top rate when they earn £32,785.

13. L. Chennells, A. Dilnot and N. Roback, A Survey of the UK Tax System (Institute for Fiscal Studies, Briefing Paper No. 9), p. 18, www.ifs.org.uk/consume/taxsurvey.pdf.

14. Ibid, p. 22.

15. William Hague announced his turn against Macpherson in a speech to the Centre for Policy Studies in December 2000. See Hague To Attack Lawrence Report In Call For More Stop And Search, The Guardian, 14 December 2000.

16. Wasting the Macpherson Opportunity, Campaign Against Racism and Fascism 53, December 1999/January 2000.

17. System Let Murderers Walk Free, Socialist Worker, 9 December 2000.

18. Racism “Remains Rife” In The Met, Financial Times, 14 December 2000.

19. Police Get License To Kill, Socialist Worker, 9 December 2000.

20. Statewatch Bulletin, vol. 8, no. 5, September–October 1998.

21. D. Gillborn and H.S. Mirza, Educational Inequality – Mapping Race, Class and Gender: A Synthesis of Research Evidence (London 2000), p. 17. The Guardian Education (31 October 2000) reported that Ofsted officials decided it was so controversial there was doubt it would be published. After the Institute of Education, where the authors are based, offered to publish it Ofsted had a change of heart – only for the report to coincidentally appear on the same day as (and be overshadowed by) the BSE inquiry.

22. Wasting the Macpherson Opportunity, op cit.

23. Labour Force Survey figures, cited in Employment Observatory Trends, no. 32 (Summer 1999), p. 91.

24. The Damning Verdict On Government Policies, The Independent, 15 April 2000.

25. Home Office, Fairer, Faster and Firmer: A Modern Approach to Immigration and Asylum (London 1998), p. 39.

26. Exclusion: New Labour Style, Campaign Against Racism and Fascism, April/May 1999.

27. Labour’s record on immigration shows that for every meagre progressive reform of the immigration rules, such as the abolition of the primary purpose rule and the ‘concession’ allowing women fleeing violent relationships to claim ‘exceptional leave to remain’, there has been a flood of attacks. These have included Jack Straw’s grisly promise to deport every passenger on the hijacked Afghan jet which arrived at Stansted airport in February 2000, Barbara Roche’s beggar-bashing, and the government’s decision to retain the essence of the Habitual Residence Test in social security which penalises black people who spend protracted periods away from Britain.

28. Home Office figures, compiled by National Coalition of Anti-Deportation Campaigns. Available at www.ncadc.org.uk.

29. The Independent, 15 April 2000.

30. Bill Morris cited in Asylum Seekers» Voucher Scheme Reforms “Shelved”, The Independent, 23 November 2000.

31. Cited in South West Consortium for Asylum Seekers, Newsletter no. 5, 3 October 2000.

32. Some 37 percent of asylum seekers who were referred to a voluntary dispersal initiative established by local authorities in the run-up to the introduction of the national scheme were unwilling to be dispersed. Audit Commission, Another Country: Implementing Dispersal Under the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 (London 2000), p. 3.

33. Currently asylum seekers must wait six months before they can apply for permission to work. Permission is often further delayed for months and may be denied. Even with permission, employers can use the asylum seeker’s insecure status to discriminate. See H. Pile, The Asylum Trap: The Labour Market Experiences of Refugees with Professional Qualifications (London 1997).

34. See Barbara Roche’s speech to the Institute for Public Policy Research in September 2000, available at www.ippr.org.uk. See also National Asylum Support Service, Full and Equal Citizens: A Strategy for the Integration of Refugees into the United Kingdom (London 2000).

35. See Work Permit Bureaucracy To Be Slashed – Blunkett, Department for Education and Employment press release 185/00, 2 May 2000.

36. S. Carmichael and C. Hamilton, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America (London 1967), p. 4.

37. K. Toolis, Race To The Right, The Guardian Weekend, 20 May 2000.

38. ‘Tyneside’s May Day march was inspiring. Around 250 asylum seekers joined local trade unionists and campaigners to unite on international workers’ day. The refugees had marched together from Newcastle’s West End carrying placards demanding an end to scapegoating. On meeting up with the main body of the march, the refugees were greeted with cheers and handshakes.’ D. Wilson, Letters, Socialist Worker, 13 May 2000. For reports of demonstrations see the Committee to Defend Asylum Seekers website at www.defend-asylum.org.

39. See, for example, S. Macaskill and M. Petrie, ‘I Didn’t Come Here For Fun’: Listening to the Views of Children and Young People who are Refugees or Asylum Seekers in Scotland (Edinburgh 2000).

40. See the Criminal Statistics for England and Wales, published annually by the Home Office.

41. A. Crawford, Crime Prevention and Community Safety: Politics, Policies and Practices (London 1998).

42. See, for example, J. Young in A. Marlow and J. Pitts, Planning Safer Communities (London 1998).

43. Metropolitan Police, Strategy Plan (London 1986), pp. 115–116.

44. Social Exclusion Unit, Bringing Britain Together (London 1998).

45. See Liberty’s website for further details. This can be found at www.liberty-human-rights.org.uk.

46. C. Rosenberg and K. Ovenden, Education: Why Our Children Deserve Better than New Labour (London 1999).

47. N. Davies, The School Report (London 2000).

48. Established under the Local Government Act 1966, Section 11 funding was extra resources made available from central government for local authorities to provide services for minority ethnic communities, such as English as a second language teachers, translators or bilingual social workers.

ISJ 2 Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 28 May 2021