C.W.R. Nevinson, French Soldiers Resting

John Molyneux Archive | ETOL Main Page

From Irish Marxist Review, Vol. 3 No. 10, June 2014, pp. 20–33.

All links have been checked and modified where necessary. (September 2020)

Copyright © Irish Marxist Review.

A PDF of this article is available here.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

Art reflects society. This statement, which is based on a core proposition of historical materialism, is fundamentally true – all art has its roots in developing human social relations – but it is also a condensation of a very complex interaction. This is because the social relations that art reflects are antagonistic relations of exploitation, oppression and resistance. So we should also remember Brecht’s words that ‘Art is not a mirror to reflect reality, but a hammer with which to shape it’. In Europe in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance art ‘reflected’ society in that a huge amount of it was commissioned by the church and religious subject matter was predominant. But this didn’t stop Michelangelo, for example, using an ostensibly religious subject, such as David, to express both revolt of the people of Florence against rule by the Medici bankers and homoeroticism. Rembrandt ‘reflected’ the early bourgeois society of the 17th century Dutch Republic by painting numerous portraits of Dutch burghers but also drew attention to, and showed his sympathy with, the outcasts of that society in his etchings of beggars. Constable ‘reflected’ the industrial revolution sweeping Britain at the time not by painting factories but by painting the English landscape as a rural idyll, much as Wordsworth and Coleridge took off to the Lake District. William Morris expressed his hatred for late Victorian capitalism by celebrating the visual culture medieval Europe.

A very large amount of art, in many different countries, reflected the cataclysm of the First World War but it did so in a wide variety of ways.

But first we should see this in historical perspective. War has been an important theme in art since war became a central feature of human society – with the division of society into classes and the development of the state. Thus in the art of Pharaonic Egypt, we find depictions of Ramses II in his war chariot; in Ancient Greece, numerous representations of the Trojan wars in sculptures and on vases; in medieval Florence, Paulo Ucello gives us The Battle of San Romano, which also pioneers the development of single point perspective. 17th century Dutch art features a whole school of maritime paintings which specializes in naval battles (reflecting the major role played by sea power in the Dutch Revolt and in the establishment of the Dutch Republic with its empire stretching from New Amsterdam to Batavia).

The overwhelming majority of all these art works, whether they are masterpieces or mediocre, do not just depict war, they celebrate it. ‘The ruling ideas in society are the ideas of the ruling class’, says Marx, ‘The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production’, and this applies even more strongly to painting and sculpture than to poetry and literature, because of its dependence on commissions, on wall space in palaces, churches and public buildings and its embodiment in very expensive physical materials (e.g. marble and bronze). Consequently, from the Parthenon marbles depiction of the Battle of the Centaurs and the Chinese Terracotta Army, through Leonardo’s lost Battle of Anghiari, Titian’s portrait of Charles V at the Battle of Marburg, to David’s Oath of the Horatii and Napoleon Crossing the Alps, and Lady Elizabeth Butler’s Scotland Forever!, we find literally innumerable works glorifying war and military leaders. 18th and 19th century British art, in particular, is filled with (generally second rate) paintings recording the progress of Britain’s military exploits and colonial conquests – Woolf at Quebec, Clive of India, Nelson, Wellington, Gordon at Khartoum, the Battle of Omdurman and so on. The only important exception to this pattern is provided by Goya’s extraordinary series of etchings The Disasters of War born out of his direct experience of the Spanish peasants’ resistance to Napoleon’s occupying army. To this day, these brutal works remain the most searing sustained indictment of the inhumanity and horror of war in the history of art. But as I said they were absolutely an exception – until the First World War.

Before we come to how that change occurred we need briefly to review the development of art leading up to the War.

The emergence of modern art dates roughly from the mid-19th century with Courbet and Manet, followed by the Impressionists (Monet, Pissarro, Sisley, etc.), Symbolists (Redon, Moreau, Klimt) and post-impressionists (Seurat, Cezanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh). In the early 20th century this development accelerated and, in artistic terms, radicalized with the swift and overlapping succession of avant-garde movements such as the Viennese Secession, Fauvism, Analytic and Synthetic Cubism, Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter (Expressionism), Orphism, Futurism, Rayonism, Vorticism and the beginnings of abstract art with Kandinsky. [1] Artistically it was cubism that was to prove the most profound and most important of these movements [2] but in the years just leading up to the War it was Futurism that held centre stage and made the biggest impact in avant-garde artistic circles across Europe.

Futurism was a poetic and artistic movement founded in Milan in 1909 by the Italian poet, Filippo Marinetti who authored its grandiloquent manifesto. Futurism was a response to the dramatic eruption of modernity – modern industrial capitalism concentrated in Italy’s northern cities – within traditional Italian society. It denounced the past and all its works in favour of the new and the modern, enthusiastically and uncritically celebrating the machine, speed, the automobile and the aeroplane. With great fanfare, Marinetti’s manifesto declares:

Given the historic moment, the extraordinary burst of urbanization combined with electrification and numerous other startling technical innovations and scientific breakthroughs, the appeal of this one-sided intoxication with the machine and speed is not hard to understand. And it managed to inspire some powerful works of art such as Boccioni’s sculpture, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space and Balla’s Abstract Sound + Speed. However, the Manifesto went on to say:

Here we see revealed the reactionary arrogance, brutality and incipient fascism that lay at the heart of Italian Futurism. [3] In the event, the eagerly anticipated War was to claim the lives of a number of Futurist artists, most notably Umberto Boccioni and the architect Antonio Sant’Elia, and destroy Futurism as an art movement. Marinetti’s militarist bravado could not survive the brutal reality of the war experience, at least not as an inspiration for avant-garde art.

Much the same happened with the British incarnation of Futurism, namely Vorticism. The Vorticist art movement was formed in 1914 by the artist and writer, Wyndham Lewis, in loose association with a number of other artists including David Bomberg, William Roberts, Christopher Nevinson, Henri Gaudier-Bresca, Jacob Epstein and Edward Wadsworth. The aesthetic of Vorticism , as displayed in its magazine BLAST [4] was a combination of cubism and futurism but Lewis’s general world view and attitude to war was similar to that of Marinetti. Nevinson was also strongly influenced by Marinetti and another influence on Vorticism was the poet, Ezra Pound, who gave it its name. Like Marinetti, Pound went on to become a fascist and Mussolini supporter. Vorticism did not survive the war. A number of the artists went to war and some became official war artists but the war changed their attitudes and their art practice. [5]

The two most important British war artists were Christopher Nevinson and Paul Nash. Between them they produced some of the most powerful depictions and expressions of the horrific reality of the war.

Nevinson was the son of a war correspondent and a suffragette. He trained as an artist the Slade School of Art. At the start of the war Nevinson joined an ambulance unit where he tended wounded French soldiers and for a while served as a volunteer ambulance driver. In January 1915 ill health forced his return to Britain but he was later made an official war artist and returned for a while to the Western Front.

At first he used a Futurist and Vorticist approach to produce extremely effective representations of soldiering which did not romanticize or glorify war but also stopped short of actually showing the slaughter. Probably the best example of his work at this period was La Mitrailleuse, which his fellow artist, Walter Sickert, called ‘probably the most authoritative and concentrated utterance on the war in the history of painting’. [6]

|

|

|

|

But Nevinson was deeply affected by his work with the wounded, especially a group he found more or less dumped and left to die in a shed outside Dunkirk. The memory of this haunted him and it was some time before he found the strength to depict it. The result when he did was a dark brooding and compassionate painting ironically entitled La Patrie in which no trace of Futurist enthusiasm remains.

|

|

At first when he became an official war artist Nevinson seemed to lose his critical edge, and focused on relatively sanitized images of aerial combat, but when, after a while, he produced tougher images he immediately fell foul of army censorship. In particular they refused to permit him to exhibit his 1917 work Paths of Glory on the grounds that it showed British dead.

|

|

Significantly this work was straightforwardly naturalist and showed no trace of Futurist/Vorticist influence.

Paul Nash, whose work is described by Richard Cork as ‘the most impressive made by any British artist during the conflict’ [7] was a very different case from Nevinson. Before the war Nash was a rather anaemic water colourist and landscape painter with no radical or avant-garde tendencies. The experience of the war transformed him and by November 1917 he was writing to his wife:

I am no longer an artist interested and curious, I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate, will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth, and may it burn their lousy souls. [8]

What Nash did to convey his message, and get round the problem of the censor at the same time, was use landscape in such a way show the full horror of the war without depicting dead soldiers.

|

|

|

|

|

|

No one looking at these pictures of land that has been tormented and tortured can fail to grasp that they are gazing on killing fields of appalling dimensions.

Some of the most haunting images of the war – they are close to unbearable to look at – come from a very unlikely source. Henry Tonks was a surgeon who became Professor of Fine Art at the Slade School of Art where he taught amongst others Augustus John, Gwen John, Wyndham Lewis, Stanley Spencer, David Bomberg, John Nash and William Orpen. When war broke out he resumed his medical career and in 1916 became a lieutenant in the Royal Army Medical Corps. This led him to produce pastel drawings recording facial injury cases.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Henry Tonks, Faces of Battle (1916) |

|

Here the most straightforward artistic naturalism turns, simply by virtue of the reality it depicts, into a devastating indictment of the war.

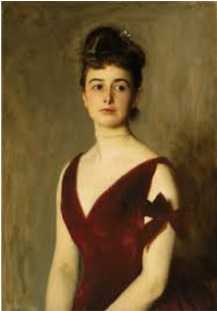

Many British artists – William Orpen, John Nash, Stanley Spencer, William Roberts, David Bomberg and others produced war related work – but the dramatic effect of the First World War on British art is, perhaps best summed up by the example John Singer Sargent. Before the war Sargent was one of London’s most successful society portraitists painting pictures like this:

|

|

|

John Singer Sargent (Pre-WW1 Portraits) |

|

Serving as a war artist turned him into the painter of this:

|

|

The story of art on the other side of no-man’s land is not, of course, the same but it is remarkable similar. In pre-war Germany it was Expressionism rather than Futurism that was artistically dominant but there were a number of links between the two tendencies (particularly via the influence of Kandinsky and Robert Delauney). In addition the powerful influence of the philosophy of Nietzsche ensured that there was no shortage of artists willing to greet the outbreak of war as a great ‘cleansing’ and ‘purification’. [9]

Two examples are August Macke and Franz Marc, founding members in 1911 (along with Kandinsky) of the Expression avant-garde group, Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). Prior to the war both produced work that was brightly coloured, optimistic even ‘exalted’.

|

|

|

|

In his major study of the period Richard Cork writes of Macke:

Like so many of his contemporaries, he greeted the declaration of war with an initial enthusiasm that led him to anticipate ‘walloping’ the French in August ... (Max) Ernst recalled, ‘Influenced by Futurism, he accepted war not only as the most grandiose manifestation of the modern age but also as a philosophical necessity’. [10]

His close friend, Franz Marc, took a similar view and both signed up to fight. But both were rapidly disillusioned by the reality. Cork continues:

Macke was sent with his Rhineland Regiment to France on 8 August. Whatever Nietzschean illusions he may have harboured about the purgative value of war were quickly destroyed. ‘It is all so ghastly that I don’t want to tell you about it’, he wrote to his wife. [11]

Within two months Macke, after fighting in seven battles, was dead – to the dismay of Marc. Eighteen months later Marc was also killed, at Verdun, but not before he produced a bleak Sketchbook from the Battlefield including The Greedy Mouth which shows the war as a strange devouring monster.

|

|

Another example is the expressionist sculptor, Ernst Barlach, for whom it was a ‘holy war’ which he depicted as a charging swordsman of ferocious power.

|

|

Three months participation as an infantry soldier in 1915 (after which he was invalided out) was enough to turn Barlach into a convinced opponent of the War and this so influenced all his subsequent work that he was later denounced by the Nazis as a ‘degenerate’ artist.

Many other German artists went through this transformation. Max Slevogt is a case that parallels John Singer Sargent. Before the war he was a painter of pleasant impressionist landscapes. He became an official war artist and what he saw turned him into an artist who produced searing indictments of the slaughter.

|

|

|

|

Otto Dix was an enthusiastic volunteer in 1914 and fought on the Western and Eastern Fronts, including at the Somme, until his discharge in December 1918. But after the war produced nightmarish prints that are reminiscent of Goya in their unflinching depiction of the brutality of war.

|

|

|

|

Käthe Kollwitz is in some ways a special case because of her politics, artistic style, gender and different, gender-related, experience. As a committed socialist (and member of the SPD) she was producing naturalistic, or one could say social realist, depictions of working people, the poor and their sufferings long before the war. She was not really part of the expressionist, cubist or futurist avant-garde and, perhaps for personal biographical reasons (the death of her siblings. including her younger brother Benjamin) death, grief and mourning were always central themes in her work. One of her most powerful pieces, Woman with Dead Child, dates from 1903. Despite this, she initially supported the war, doubtless influenced by the SPD, but then in October 1914 her son, Peter, was killed on the battlefield and this sent her into prolonged depression. However, she turned profoundly against the war and eventually came to the conclusion ‘that Karl Liebknecht was proved right’. [12] Her artistic response to the war focused not on the horror of battle but on the grief of widows and mothers.

|

|

|

|

Perhaps the most radical of all the war artists was George Grosz who viewed the war with hostility from the start and already in 1914 produced an ink drawing, Pandemonium, which depicted crowds in the grip of ‘patriotic’ frenzy and war fever. In 1915 he made a series of drawings and lithographs which, in the words of Richard Cork, were ‘obsessed with corpses’ such as Battlefield with Dead Soldiers and The Shell. But what also distinguished Grosz was the satirical savagery with which he depicted the profiteers and bourgeois whom he held responsible for the war.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Grosz was an active revolutionary as well as an artist. He took part in the Spartacist Rising of January 1919 and went on to be a founder member of the German Communist Party.

What has been presented here is, necessarily, a highly selective sample of the vast amount of art generated by the First World War in all the belligerent countries. A huge number of artists produced war related work – John Nash, Stanley Spencer, William Roberts, William Orpen, Albin Egger-Lienz, Oscar Kokoshka, Natalia Goncharova, Max Beckmann, George Leroux, Fernand Leger, Pierre Bonnard and Felix Vallotton are just a few of those not specifically discussed here. Consequently a comprehensive survey is completely beyond the range of this article. What I have tried to show is the general trajectory of war art at the time, which was overwhelmingly in the direction of opposition to the war, and some of what I consider to be the most powerful images.

However, there is one further and very different artistic reaction to the war which needs to be highlighted – that of the Dadaist movement. At the start of this article I noted that Constable ‘reflected’ the industrial revolution by painting its opposite, the English countryside, my point being that the fact that the relationship between art and its social context is often complex and dialectical does not make that relationship any the less real. Dadaism responded to the war not by depicting its battles or its horrors but with its own iconoclastic revolt against all past and existing culture.

Dada was founded in early 1916 at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich by a group of artists and poets who included Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, Richard Huelsenbeck, Hans Arp, Marcel Janco and Hans Richter. As Dawn Ades notes, ‘It was essentially an international movement: of the Zurich Dadaists, Tzara and Janco were Rumanian, Arp Alsatian, Ball, Richter and Huelsenbeck were German.’ [13] What brought them to Zurich was the same thing that brought Lenin there – its location in neutral Switzerland. The participant, Hans Richter, observes:

To understand the climate in which Dada began, it is necessary to recall how much freedom there was in Zurich, even during a world war. The Cabaret Voltaire played and raised hell at No. 1 Spiegelgasse. Diagonally opposite, at No. 12 Spiegelgasse, the same narrow thoroughfare in which the Cabaret Voltaire mounted its nightly orgies of singing, poetry and dancing, lived Lenin. Radek, Lenin and Zinoviev were allowed complete liberty the Swiss authorities were much more suspicious of the Dadaists, who after all were capable of perpetrating some new enormity at any moment, than of those quiet studious Russians even though the latter were planning a world revolution. [14]

Dada was born out of disgust at the war. Richard Huelsenberg wrote in 1920, ‘we were agreed that the war had been contrived by the various governments for the most autocratic, sordid and materialist reasons’. [15] Whereas Lenin and his comrades aimed to turn the imperialist war into a civil war and thus overthrow capitalism, the Dadaists declared war on the art and culture of a rotten society believing that it was irredeemably corrupted and complicit. To all official and established art they counterposed the defiant and nihilistic gesture, art that claimed to be anti-art.

The idea of destroying bourgeois art with art or with gestures was always an illusion – capitalist society and the capitalist art world has demonstrated again and again its ability to incorporate this kind of artistic rebellion. And viewed in retrospect the actual art works produced by the Zurich Dadaists do not stand out as exceptionally radical, outlandish or extreme within the story of modern art. Nor do they appear as in any way protests against the war.

|

|

|

|

Nevertheless the Dada concept and the Dada attitude proved highly fertile in terms of the development of modern art in the 20th century. Within a few years there were Dadaist groups in Berlin, New York, Paris, Cologne and other cities involving artists as diverse as Max Ernst, Francis Picabia, George Grosz and John Heartfield (the great photomontage artist). Dada typography was taken up by Russian constructivism. Dada also led directly to Surrealism, perhaps the most important and influential avant garde art movement after World War I. And in New York Dadaism produced the genuinely iconoclastic work of Marcel Duchamp, which really did change the course of modern art and our whole understanding of what constitutes art.

|

|

|

|

Having thus shown the profound effect of the First World War on European art at the time, it remains to try to say why this happened, why the artistic response to the war was so qualitatively different to any previous war (war, after all, has always involved immense brutality) and then to reflect on longer term consequences of this.

When it is matter of understanding why art developed as it did Marxism, with its historical materialist method, comes into its own. As Trotsky wrote:

It is very true that one cannot always go by the principles of Marxism in deciding whether to reject or to accept a work of art. A work of art should in the first place be judged by its own law, that is, by the law of art. But Marxism alone can explain why and how a given tendency in art has originated in a given period of history. [16]

Nevertheless, even with the aid of historical materialism, such explanation, seeking to show the relationship between general social historical development and specific developments within in the history of art, must involve a certain element of speculation. As Marx noted:

It is always necessary to distinguish between the material transformation of the economic conditions of production, which can be determined with the precision of natural science, and the legal, political, religious, artistic or philosophic – in short, ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out. [17]

In this case I think we can identify the convergence of two main historical phenomena: the changed social position of artists and the specific nature of the war.

From about 1848, when the bourgeoisie lost its role as a revolutionary class and moved firmly into the camp of reaction, a split opened up between the more advanced artists and the aristocratic/bourgeois ruling classes. Beginning with Courbet and progressing through the Impressionists to the likes of Seurat, Van Gogh, and Toulouse Lautrec the artists, in Clement Greenberg’s phrase ‘migrated to Bohemia’. We are not talking about proletarian art here – the artists remain predominantly of middle class origin and petty bourgeois in their objective class position [18] – but in many cases they live and work along side the working class and the poor and this is reflected in the art – its subjects and their treatment. Courbet paints stone breakers and supports the Paris Commune, Seurat depicts workers on the banks of the Seine, Van Gogh paints peasants and postmen not kings and emperors, and Picasso’s blue period gives us the Parisian poor. The development of capitalist society with its growing educated middle class also made it more possible for artists to survive, albeit with difficulty, by selling their work, independently of state, church or ruling class patronage. [19] In art, as in life, there were right wing as well as left wing tendencies but both right and left were in some sense in revolt against the old order. Thus, the late 19th and early 20th century prepared the ground for artistic revolt against the war.

However, the main factor was undoubtedly the character of the war itself. The imperialist nature of the war and the absence of a significant element of national liberation was important in that, once the early illusions disappeared, there was widespread perception that it ‘wasn’t worth it’ and that lives were being sacrificed ‘for nothing’ i.e. for no legitimate political or moral purpose. But history had long been replete with brutal dynastic and imperialist wars, without producing anti-war art. Here the sheer scale and duration of the war, and of the slaughter, was hugely important. Previous wars had fought largely either by mercenaries or relatively small professional armies and even if they lasted a long time consisted of a series of battle of shortish duration. There was no precedent for the mass conscription and prolonged war of position in trenches that dominated the First World War.

This meant, as we have seen in our brief survey, that significant numbers of artists were drawn into the war as participants, and became casualties, in a way that had not happened before. The enormous casualty rate also ensured that the war reached back into and affected the whole of society. When in his Anthem for Doomed Youth, the poet Wilfred Owen evokes the image of young men drawn from ‘sad shires’ and ‘the drawing down of blinds’ we see this happening all across England. No town or village, scarcely a family, remained untouched by the catastrophe.

Thus history created both a supply of potentially anti-war artists and a social demand for anti-war art. Moreover the shift from initial, naive, enthusiasm to bitter disillusionment and opposition which we have seen among artists was a reflection a much wider societal reaction.

When it comes to consequences we can note three main things. First, the profusion of anti-war art became part (a small part, of course, compared to the revolt of the masses) of the struggle against the war, not just ‘a mirror to reflect reality but a hammer to shape it’. Second, the art, like the poetry and novels, helped to fix the image of the war as a disaster in the popular consciousness and social memory, thus making it much more difficult to rehabilitate it or retrospectively ‘celebrate’ it. Third, it put an end – one cannot say ‘forever’ but up to the present and for the foreseeable future – to art that seeks to romanticise or glorify war and that is a small but permanent step forward.

1. The pivotal role of Picasso’s Les Demoisel les D’Avignon in this process is discussed in John Molyneux, A revolution in paint: 100 years of Picasso’s Demoiselles, International Socialism 115, July 2007. http://www.isj.org.uk/?id=341.

2. See John Berger, The moment of cubism, in The Moment of Cubism: And Other Essays, London 1969.

3. In 1919 Marinetti was to co-write another famous manifesto – the Fascist Manifesto of Benito Mussolini.

4. BLAST was edited by Lewis. Only two issues appeared, one in Summer 1914 and one in 1915, but they had a lasting impact on British art.

5. With the partial exception of Wyndham Lewis.

6. Walter Sickert, The Burlington Magazine, September/October 1916.

7. Richard Cork, A Bitter Truth: Avant-Garde Art and the Great War, Yale University Press, 1994, p. 196.

8. Paul Nash (1949), Outline: an autobiography and other writings, Faber and Faber, London.

9. The backing of the war by German Social Democracy was also a significant factor in securing the initial support of many artists including Käthe Kollwitz who will be discussed later.

10. Richard Cork, as above, p. 42.

11. As above, p. 43.

12. Karl Liebknecht, close comrade of Rosa Luxemburg, voted 1 out of 111 SPD Reichstag deputies against War Credits. He went on to form the Spartakus League (forerunner of the German Communist Party, and participate in the Spartakus Rising in the German Revolution. As a result he, along with Rosa Luxemburg, were murdered by counter-revolutionary Freikorps in January 1919. Kollwitz marked his death with a powerful woodcut, Memorial Sheet for Karl Liebknecht.

13. Dawn Ades, Dada and Surrealism, in Nikos Stangos (ed.), Concepts of Modern Art, London 1981, p. 111.

14. Hans Richter, Dada: Art and Anti-Art, London 1966, p. 16.

15. Cited in Dawn Ades, as above, p. 111.

16. L. Trotsky, Literature and Revolution, London 1991, p. 207.

17. K. Marx, 1859 Preface.

18. In their large majority, artists remain owners of their own means of production, and sellers of the products of their labour, not of their labour power.

19. In a way that was not possible for Goya or Velasquez or Michelangelo.

John Molyneux Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 22 September 2020