John Molyneux Archive | ETOL Main Page

From Irish Marxist Review, Vol. 11 No. 34, November 2022, pp. 9–31.

Copyright © Irish Marxist Review.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

The present crisis is in important respects unprecedented and symptomatic of a capitalist system which is in profound decay. It is what Gramsci called an ‘organic crisis’ and comprises multiple interlocking elements. These statements are not made lightly and the first purpose of this article is to justify them. Its second purpose is to draw out some political conclusions from this diagnosis.

Let us begin with the obvious, and what is obvious is that there are four main elements in this crisis: the economic crisis of inflation and likely recession; the health crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic; the geo-political crisis of the Ukraine War and growing international tension; and the climate change crisis.

I will take each of these in turn, starting with the economy.

Approximately twenty thousand people marched through Dublin on September 24th in what was the largest demonstration since the campaign to Repeal the 8th Amendment in 2018. It was called by the Cost of Living Coalition. This is because the economic crisis of capitalism currently presents itself first and foremost in terms of inflation. The current rate of inflation in Ireland stands at 8.7 percent for August 2022, slightly down from 9.1 percent in July, the highest for thirty-eight years.

This is part of an international trend with inflation across the Eurozone running at 10 percent; in Germany at 10 percent; in the UK at 9.9 percent; in the Netherlands at 14.5 percent, in Russia at 13.7 percent, Sweden 9.8 percent and in the US at 9.1 percent. Obviously rates vary considerably by country, with China claiming only 2.5 percent, Japan 3 percent, France 5.6 percent (still considerable), and India 7 percent. But in Poland it is 17.2 percent, Ukraine 24.6 percent, and Nigeria 20.5 percent. There are also a number of countries where the figure is extremely high, for example Argentina at 78.5 percent, Turkey 83.5 percent, and Sudan 125.4 percent. [1] In terms of the impact on the mass of people, this is compounded by the fact that in many countries the rate of increase of the essentials of food and energy is above the general rate of inflation. In the US, food prices are rising at 11.1 percent and energy at 32.9 percent. In the UK, the rate for food is 13.1 percent and energy a massive 57.7 percent. Across the OECD it is 14.4 percent for food and 35.2 percent for energy.

The cause of this inflationary surge is ‘officially’ attributed (i.e. by our and other Western governments) to the war in Ukraine – ‘Don’t blame us, blame Putin!’ is their message. In reality prices had started on their upward spiral before Putin’s invasion. The Ukraine War is, of course, a substantial contributor, particularly by virtue of its effect on energy prices, but before Ukraine there was the Covid-19 pandemic, which severely disrupted multiple supply chains and created an accumulation of unspent funds looking for an outlet in the hands of the middle classes, and climate change, which is seriously affecting food production and driving food prices up.

While the inflationary impact of energy prices on food costs is readily apparent, it is becoming clear that climate issues are also a growing inflationary force and one that is likely to intensify.

At its most simplistic, climate change, resulting in rising global temperatures and environmental degradation, is eroding agricultural productivity, driving up the cost of food ... As the planet is placed under greater stress, its productivity will fall. According to the IPCC WGII Sixth Assessment Report, published in October 2021, global warming is affecting agricultural productivity in both land- and ocean-based systems. Crop yields are impacted by degrading soil conditions; rising temperatures affect crop developments, and extreme weather impacts crop harvests. [2]

Then there is the factor never mentioned by mainstream commentators, the massive competitive profiteering by big corporations. Thus, in the second quarter of 2022, British Petroleum (BP) tripled its profits to £7 billion [3], Shell raised its earnings to $11.1 billion (up from $9.1 billion in the first quarter) [4], and in July, Exxon Mobil announced second-quarter earnings of a staggering $17.85 billion, up from ‘only’ $5.48 billion in the first quarter. [5] This is particularly important in the context of a long period of stagnant or declining profits in what Michael Roberts has called ‘the long depression’ since 2008. [6]

Inflation is very troublesome and dangerous for capitalism and capitalist governments. In the first place it is highly disruptive of their own projects and ‘action plans.’ For example, a headline in the Business Post on the 9th of October read, ‘Soaring inflation puts “vital” new gas-fired power plants at risk.’ [7] Similarly, as Kieran Allen has pointed out, inflation has driven a coach-and-horses through the already inadequate plans of the Irish government for rolling out electric cars (to reduce carbon emissions) and for tackling the housing crisis. [8] And this applies internationally. The absolute mess the (admittedly incompetent) British Tory government has gotten into over recent weeks is evidence of this. Here it is worth noting that, alongside the comic-opera meltdown of Liz Truss and her cabinet with their spinning U-turns, they nearly collapsed the UK pensions market, which would have had catastrophic implications.

In the second place, inflation generates mass resistance. It can lead – as it has in the UK and Northern Ireland in recent months, and as it did in the UK, Ireland, and elsewhere on a huge scale in the late 1960s and ’70s – to wage militancy and strike waves. It can also produce mass riots and feed into revolutionary outbursts. It is not accidental that the two countries seeing the most dramatic popular uprisings in 2021 have been Sri Lanka and Iran. [9] In Sri Lanka in July, inflation was running at 60.2 percent, and in August it surged to 70.2 percent. [10] In Iran it is currently at 52.2 percent. [11] Price hikes, especially in the price of bread, were a background feature of the Arab Spring in 2011, and it is worth remembering that the closest Germany ever came to a socialist revolution (that would have changed world history) was during the crazy hyperinflation of the summer and autumn of 1923. [12]

Precisely because inflation is so dangerous to the system, it became capitalist orthodoxy that suppressing it was the first priority of economic policy. This was what lay behind the shift in the late seventies from the hitherto dominant Keynesianism to what was then called the ‘monetarism’ of Thatcher, Reagan, Milton Friedman, and the Chicago School. Their central idea was that inflation was caused by ‘too much money chasing too many goods’ and that the remedy for inflation lay in governments acting to restrict the money supply. The main mechanism for doing this was by raising interests. This was what was done by Paul Volker of the US Federal Reserve Bank in 1979-84, and the effect was indeed to curb inflation but also to plunge the US and much of the world into a deep recession. [13]

In this respect, there are many signs that history is repeating itself. The US Federal Reserve Bank has started to raise interest rates – by 0.75 percent three times so far this year – and as I write these lines, Reuters reports:

The Federal Reserve is seen delivering another large interest-rate hike in three weeks’ time and ultimately lifting rates to 4.75–5 percent by early next year, if not further, after a government report showed inflation remained stubbornly hot last month. [14]

The likelihood is that this will tip the already fragile global economy into recession with immense if incalculable economic, social, and political consequences.

In terms of the mainstream media and mainstream political discourse, the pandemic is now being treated as effectively over, a nightmare from which we have successfully emerged thanks largely to vaccination programmes and which is best forgotten about.

But the most elementary facts fail to bear this out. According to the officially registered figures, global cases are currently running at about five hundred thousand cases a day (548,075 on September 14th, 2022). This compares to 3.8 million cases on January 29th, 2022, at the very height of the pandemic, and 1.2 million in July 2022, or indeed 440,000 in February 2021. In other words, things are far better than they were at their worst, especially in terms of deaths rather than cases – a current average of 1,500–2,000 a day, compared 16,600 a day in January 2021 – but certainly not ‘over.’ Also, it is increasingly evident that while vaccination programmes have been crucial for mitigating the spread and seriousness of infection, they not by themselves been capable of eliminating the virus or offering guaranteed protection against it, even for the vaccinated. It remains, at the very least, possible that there will be further Covid-19 surges.

But what is the scale of the disaster so far? According to the ‘official figures’ (i.e., officially registered cases and deaths), total global cases stand at 617,108,036 and total deaths at 6,530,616. This is a higher death toll than any war since WW2. However, these figures mask a multitude of problems. First, the enormous variation between different countries. For example, in the US there have been ninety-seven million cases and over one million deaths (compared to US deaths of 655,000 in the Civil War, 405,000 in WW2, and 58,000 in Vietnam), whereas in India, a country with more than four times the population, there have been, on official figures, only forty-four million cases and 528,000 deaths, giving a death rate of only 375 per million of the population compared to 3,218 per million in the US.

What explains such a great disparity, with the much poorer country seeming to fare so much better than the much richer country? Moreover, this apparent anomaly turns out to be far from rare. Thus, Bangladesh, one of the poorest and most densely populated countries in the world, with a population nearly half that of the US, reports only two million cases and 29,000 deaths, giving a death rate of only 174 per million. One possible explanation for these otherwise puzzling variations may lie in the countries’ respective testing regimes: the US, with a population of 335 million, has carried out 1,110 million tests, or 3.3 million per million of the population; in contrast, Bangladesh, with a population of 168 million has administered only 14.8 million tests, or only 88,000 per million. India provides an intermediate case with 891 million tests in a population of 1.4 billion, or 632,100 per million.

But once we start to interrogate the official statistics in this way, their wider reliability comes into question. For example, how credible is it that in Nigeria, population 217 million, there have been only 3,155 recorded deaths, or fifteen per million, or that in China, population 1.4 billion, there have been only 5,226 recorded deaths, or four per million, when in little Ireland there have been 7,862, or 1,554 per million?

Obviously such an in-depth investigation of these statistics could continue almost indefinitely and would probably require at least a book-length study, but two reports – by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Economist magazine – provide a very useful corrective. On May 5th, 2022, the WHO reported:

New estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO) show that the full death toll associated directly or indirectly with the COVID-19 pandemic (described as ‘excess mortality’) between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2021 was approximately 14.9 million (range 13.3 million to 16.6 million). [15]

And the Economist estimates a death total of twenty-two million, or 3.4 times the official figure, with a possibility of over twenty-four million. World in Data comment:

This work by The Economist is one of the most comprehensive and rigorous attempts to understand how mortality has changed during the pandemic at the global level. But these estimates come with a great deal of uncertainty given the large amount of data that is missing and the known shortcomings even for data that is available.

We can think of them as our best, educated – but still ballpark – estimates. Some of the specific figures are highly uncertain, as the large uncertainty intervals show. But the overall conclusion remains clear: in many countries and globally, the number of confirmed deaths from COVID-19 is far below the pandemic’s full death toll. [16]

So any kind of certainty or exactitude is impossible, but it is clear we are looking at a death toll that exceeds that of WW1 and that this in turn ignores the wider economic and social implications of this global calamity: the loss and disruption of production with its implications for inflation, the augmentation of poverty and inequality, the increase in mental distress, the assistance it rendered (in some countries) to the far right and conspiracy theorists, and so on.

But however deeply we investigate the effects and consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic, we still fail to grasp its dimensions if we do not refer to its causation and to the likelihood of its recurrence. These questions are for all intents and purposes completely passed over in the mainstream discourse, but they are obviously linked and of profound importance. Covid-19 is an example of zoonotic infection, a virus that has leapt from animals to humans. And as the Marxist epidemiologist Rob Wallace has shown, such cross-infection is made enormously more likely by the profit drive of giant agri-business to encroach ever deeper into the wild and by modern methods of intense large-scale factory farming. Then the spread of any such infection is made wider and more rapid by the huge expansion in global food chains and global travel.

As Lee Humber put it at the start of the pandemic:

Viral epidemics are not uncommon. This year’s flu season is shaping up to be the worst in years, according to the US Centre for Disease Control. In the US alone there have been 19 million illnesses, 180,000 hospitalisations and 10,000 deaths ...

Globally, the 2009-10 strain of flu – H1N1 (2009) – killed 579,000 people in its first year, although this was fewer than predicted. It produced long-term complications in 15 times as many cases as initially projected, having spread globally in less than nine days. Major flu epidemics have been a constant feature across North and South America in the 21st Century. This is the context in which to understand the coronavirus outbreak, which began in China. We live in a world in which there is a real threat of deadly viral pandemics ...

Industrial practices inherent in the capitalist mode of production, now globalised and intensified by 50 years of neoliberalism, are actively breeding more and more virulent and deadly pathogens. This pattern of epidemics is not accidental. It is a consequence of the way the food we eat is produced. [17]

In other words, the possibility of the emergence of a different virus, even a more deadly virus, in the not too distant future, is all too real. As Rob Wallace, reflecting on the succession of viruses in recent years before Covid-19, ominously put it:

Hendra, Ebola, Malaria, SARS, XDR-TB, Q fever, simian foamy virus, Nipah, and influenza. One of these bugs, or an as yet undiscovered cousin, will likely kill a few hundred million of us someday soon. [18]

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the war that has followed it has, with no end in sight, already claimed many thousands of lives and raised the spectre of the use of nuclear weapons in a way not seen since the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. The Doomsday Clock, maintained by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, was set at seven minutes to midnight in 1947 at the onset of the Cold War; it was put back to seventeen minutes to midnight in 1991, and set at one hundred seconds in 2022. [19]

If the statistics on the pandemic are unreliable, those for casualties in Ukraine are even more so. This is often ascribed to the ‘fog of war,’ as if it were a weather phenomenon, when really it is the fog of war propaganda and lies. However, various current estimates suggest Russian military casualties run to over 20,000 killed and perhaps much more injured, up to say 100,000, with a similarly broad range of estimates for Ukrainian military and civilian casualties. [20]

But whatever the truth of these claims, what is beyond dispute is that the war has produced a massive exodus of refugees. According to the UN, over one million refugees fled Ukraine in the first week of the invasion, rapidly rising to eight million but then falling to 6.1 million as some refugees returned. To this should be added the figure of approximately eight million displaced within the country. Regarding the destination of refugees, the UN High Commission for Refugees states that, as of May 13th, there were 3,315,711 refugees in Poland, 901,696 in Romania, 594,664 in Hungary, 461,742 in Moldova, 415,402 in Slovakia, and 27,308 in Belarus, while Russia reported it had received over 800,104 refugees. As of March 23rd, over 300,000 refugees had arrived in the Czech Republic. Turkey has been another significant destination, registering more than 58,000 Ukrainian refugees as of 22 March, and more than 58,000 as of 25 April. [21]

To this we must add the economic impact of the war. Here we have to note that for the Irish government and many other governments Ukraine is serving as their alibi for the cost-of-living crisis and soaring energy prices, when in fact the inflationary surge began before the Russian invasion. Nevertheless, the war has undoubtedly made things considerably worse, and the fact that the region is one of the world’s largest producers of wheat and grain has had major consequences.

According to the European Commission, Ukraine accounts for 10 percent of the world wheat market, 15 percent of the corn market, and 13 percent of the barley market. With more than 50 percent of world trade, it is also the main player on the sunflower oil market. According to statistics from the US Department of Agriculture, Ukraine was the world’s seventh-largest producer of wheat in 2021/22, with thirty-three million tons. Only Australia, the US, Russia, India, and China produced more. [22]

Ukraine exported up to 6 million tonnes of grain a month before Russia invaded the country on Feb. 24, but in recent months the volumes have fallen to about 1 million tonnes, sparking global grain shortage concerns and price spikes. Ukraine reached 54.9 million tonnes of wheat, corn and barley exports in 2019–2020, but dipped to 44.9 million tonnes in 2020–21, mostly on lower wheat production, according to the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Feb. 1 Foreign Agricultural Services (FAS) quarterly report. Before Russia’s invasion, Ukraine had been projected to export 63.7 million tonnes of the grains in 2021–22. [23]

Inevitably, the most devastating impacts of this have been seen in north-eastern African countries (Somalia, Ethiopia, and Kenya, among others), which were already poor and suffering food insecurity due to climate change related droughts, but the consequences are also severe across North Africa and the Middle East. Yemen is an example. Yemen imported 90 percent of its food, including 42 percent of its wheat, from Ukraine, and the country, affected by seven years of devastating war, saw the price of basic foods increased by up to 45 percent between March and June of this year. Indeed, ultimately, they impact the total global market.

It would, however, be a serious mistake to treat the Russian invasion and subsequent war as if it was a stand-alone shock, a factor exogenous to the system as a whole which suddenly erupted to disturb business as usual. Even in the narrowest factual terms this is not the case, in that Russian and Ukraine had been engaged in an ongoing war, largely ignored by the media but claiming about ten thousand lives, since 2014. But the main point is that the current war is just one episode, one particular escalation, in a developing global inter-imperialist rivalry. Five years ago I wrote following:

At the same time we see the return, especially over the Ukraine, of the spectre of the Cold War, supposedly long laid to rest. Even more importantly in the long run, we see growth of tension between the US and China in the South China Sea which is symptomatic of emerging rivalry between the world’s two largest economies. In terms of real policy rather than media rhetoric (overwhelmingly focused on the threat of Muslim ‘extremists’) the US under Obama has already undertaken its ‘Asian pivot’ making China the real object of its long-term strategic concerns.

While US share of world GDP has been declining, that of China has been rising (from 4.5 percent in 1950 to 15.4 percent in 2014) displacing first Germany and then Japan in the pecking order of the world economy and placing it within striking distance of the US. What this could mean in military terms is shown by a 2014 report from the UK Ministry of Defence which outlines projected defence expenditure of major powers for the year 2045 as follows:

|

Obviously, such a projection for thirty years ahead is guess work but it is a guess that will haunt the minds of the strategists in the Pentagon. And one thing we can be fairly sure of is that fear of such parity will drive the policies of the American ruling class for decades to come. An era of peace and stability is not on the agenda. [24]

The US and its NATO allies saw in Putin’s invasion a major opportunity: a) to recoup the ground lost in their defeats in Iraq and Afghanistan; b) to seriously weaken Russia by means of a proxy war ‘to the last Ukrainian,’ without the political risk of US or EU casualties; c) to over-reinforce the hegemony of the US over its European allies as a leader of ‘the democracies’ against the ‘authoritarian’ states. Whatever the immediate outcome in Ukraine, which remains unpredictable, it is clear that this will be only an episode in an ongoing conflict likely to stretch into the foreseeable future.

Inter-imperialist rivalries go back over centuries: England versus the Dutch in the seventeenth century; Britain versus France in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; Britain and France versus Germany and Austria in the first half of the twentieth century; the US versus the Soviet Union in the Cold War. These rivalries have involved numerous wars: the Anglo-Dutch Wars of 1652–54 and 1665–67; the Seven Years’ War of 1756–63; the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars of 1793–1815; the First World War; the Second World War; the Korean War; the Vietnam War – to cite only the leading examples. It is more than likely that the same will happen in the twenty-first century with incalculable consequences.

The three crises we have discussed so far – the economic, the pandemic, and the Ukraine War – have tended to eclipse the environmental crisis in terms of government responses during this year; witness the substantially reduced media hype surrounding the Cop 27 conference in Sharm El-Sheikh compared to Cop 26 in Glasgow in 2021. But in reality, far from abating, it has actually become much more severe, and it remains ultimately the most intractable and most dangerous of the multiple threats faced by humanity. The environmental crisis emphatically cannot be reduced to climate change. It has many different dimensions ranging from river and air pollution to toxic waste in working-class neighbourhoods, to the biodiversity crisis [25], all of which are symptomatic of the metabolic rift between capitalism and nature, but I will focus here on the question of climate, because it is the leading and most devastating edge of the overall crisis.

The very specific geological and climatic position of Ireland insulates it from much of what is afflicting the planet globally, but here is a succinct summary by John Bellamy Foster of recent events in terms of heat waves:

Since the 1980s, there has been a seven-fold increase in concurrent large heat waves affecting multiple regions in the medium and high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. A large heat wave is defined in the scientific literature as a high-temperature event lasting three or more days, occupying at least 1.6 million square kilometers (close to the size of Alaska). Concurrent heat waves of this size or larger have increased by 46 percent in mean spatial extent over the last four decades. In the 1980s concurrent heat waves occurred approximately twenty days per year. This has now risen to 143 days, with a maximum intensity 17 percent higher.

This July, concurrent heat waves spread across the Northern Hemisphere threatening the lives, living conditions, and general welfare of hundreds of millions of people. Major wildfires arose in Greece, Portugal, Spain, and France. In Spain and Portugal alone, more than 1,700 people died from the July heat waves and wildfires. Temperatures in the United Kingdom broke all historic records. In North America, tens of millions were subjected to searing heat, drought, and out-of-control wildfires. Heat waves also struck North Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, South Asia and China. The vast territorial range of these concurrent heat waves, stretching around the globe, indicates that heat waves and other extreme weather events emanating from climate change are now emerging as a universal phenomenon requiring universal solutions.

The other side to heat waves is flooding. In recent weeks we have all seen the appalling floods that have hit Pakistan, with thousands dead and millions displaced, but this is only one extreme example of an epidemic of disastrous flooding. In July 2021, severe floods spread across Europe. They started in the UK but then moved to several river basins, including in Austria, Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and elsewhere. At least 243 people died, including 196 in Germany. The Belgian minister of home affairs described the events as ‘one of the greatest natural disasters our country has ever known’. [26] In Durban, severe flooding and landslides caused by heavy rainfall on 11–13 April of this year caused the death of 448 people, displaced over 40,000 people, and completely destroyed over twelve thousand houses in the south-east part of South Africa. In Kentucky in July, a total of thirty-eight people were killed as a direct result of floods, and these in turn were part of wider flooding which claimed forty-eight lives in all. In Australia there were, in this year alone, life-claiming floods in January, February March, and July. As I am writing these words, on September 23rd, the website Flood List reports as occurring over the last few days deadly floods in Nigeria (300 dead, 100,000 displaced), Niger (168 dead, 227,000 displaced), Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. [27]

Unfortunately, the most important, ultimately decisive facts about climate change can only be expressed in the language of dry, ‘abstract’ statistics, not emotive human consequences. First there is the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Carbon dioxide measured at NOAA’s Mauna Loa Atmospheric Baseline Observatory peaked for 2022 at 420.99 parts per million in May, an increase of 1.8 parts per million over 2021, pushing the atmosphere further into territory not seen for millions of years. Scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, which maintains an independent record, calculated a similar monthly average of 420.78 parts per million.

|

Carbon dioxide levels are now comparable to the Pliocene Climatic Optimum, between 4.1 and 4.5 million years ago, when they were close to, or above 400 parts per million. During that time, sea levels were between 5 and 25 meters higher than today, high enough to drown many of the world’s largest modern cities. Temperatures then averaged 7 degrees higher than in pre-industrial times. [28]

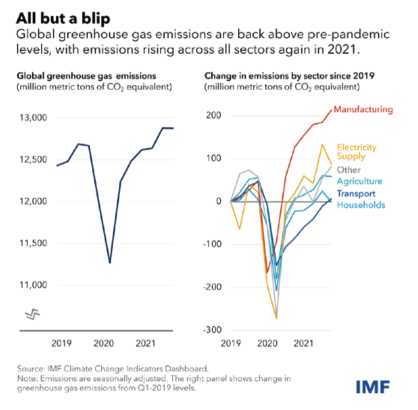

The fundamental fact is that, no matter what declarations are made by politicians, what plans and pledges are issued by governments or mission statements by corporations, as long as this easily checkable statistic continues to rise, global warming will continue. So what is the current trend? According to the IMF, emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases plunged 4.6 percent in 2020, as lockdowns in the first half of the year restricted global mobility and hampered economic activity, but in 2021 annual global greenhouse gas emissions rebounded 6.4 percent last year to a new record, eclipsing the pre-pandemic peak as global economic activity resumed.

The problem is that these statistics do translate inexorably into an ever-growing tide of terrible disasters which we see on our television screens, a few of which I listed above.

This horrific prospect should not however be taken to mean that humanity faces imminent extinction. This was an understandable but mistaken conclusion that many activists drew from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report in 2018. But the notion that the IPCC was predicting human extinction by 2030 was wrong. It was saying that we had until 2030 to stay within 1.5 °C warming. Today we can say that it is almost certain that warming will exceed 1.5 °C and that it will most likely head for more than 2 °C in short order, but the world population is close to eight billion, and that many people will not be wiped out overnight. What it means is those eight billion will face increasing climate-generated disasters, but they will be able to respond and fight back.

The most striking and significant feature of the four crises discussed above is how they intersect and interact with each other to form an organic crisis of the capitalist system as a whole. I now want to look at some examples of this intersection, advance a proposition about theorising the root of the crisis, and then consider the political implications, including the implications for socialist strategy.

When we looked at the causes of the cost-of-living crisis, we found that the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and climate change, along with profiteering of course, were all factors in the surge in inflation. When we looked into the causes of the Covid-19 pandemic, we found it was profoundly linked to capitalism’s relationship to nature, to the metabolic rift between society and nature that also lies at the root of climate change. When we look at the responses to Covid-19 of governments and the effects of the pandemic, we find they were deeply affected by the commitment to profit and by the class and racialised structure of society. [29] The inter-imperialist rivalry fuelling the war in Ukraine and careering towards conflict with China has among its causes not only the economic and military rise of China but also the relative decline of the US, itself a product of the underlying decline of the rate of profit. The war in Ukraine immediately served as an excuse for governments to long-finger plans to combat climate change and move away from fossil fuels while the war itself also threatens an environmental catastrophe at Ukraine’s fifteen nuclear plants. Above all, we have the fact that if the system (and it is a very big if) is able to negotiate the cost-of-living crisis without plunging into recession, or even if it emerges the other side of recession and resumes capitalist economic growth, this will only drive further climate change, and escalating climate change means poverty, hunger, war, and uncountable refugees. So capitalism has no foreseeable way out the crisis other than through unimaginable catastrophes.

A useful way of theorising the organic nature of this crisis is to go back to Marx’s classic statement on the dynamics of history and revolution in his Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy.

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production ... At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or – this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms – with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution. [30]

The contradiction between the development of the forces of production and capitalist relations of production lies at the heart of all the crises we face as well as their manifest interconnection. In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels wrote, ‘The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the instruments of production,’ and that it ‘has accomplished wonders far surpassing Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts, and Gothic Cathedrals.’ That was written in 1848. Consider these figures:

|

World GDP Total output of the world economy adjusted for inflation |

||

|

1000 |

$210.14 billion |

|

|

1500 |

$430.53 billion |

[c. The Renaissance and Reformation, Columbus] |

|

1820 |

$1.20 trillion |

[c. The Industrial Revolution] |

|

1900 |

$3.32 trillion |

[c. Classic imperialism] |

|

1950 |

$9.25 trillion |

[c. post-WW2 – beginning of ‘the great acceleration’] |

|

2015 |

$108.12 trillion |

|

|

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/world-gdp-over-the-last-two-millennia |

||

By their very nature these figures, especially the older ones, are approximations, and the method of calculating them can be disputed in numerous ways, but the basic facts that for thousands of years growth of global production was at a snail’s pace, that with the birth of capitalism in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries it started to speed up, that the Industrial Revolution was a huge turning point, and that since WW2 (with the Anthropocene and ‘the great acceleration’ as it is known [31]) production has exploded – these are indisputable. And with this expansion of the productive forces have come huge increases in scientific knowledge, in technology, and in medicine of all kinds. And yet humanity is still staring at catastrophe.

In the most immediate national terms this means that Ireland can be ranked the third-richest country in the world (by GDP per capita [32]) and yet have over ten thousand people in homeless accommodation and approximately 20 percent of its population in poverty. Particularly telling is the story of the United States, which we are so accustomed to thinking of as the richest country in the world. The US is still, in absolute terms, the biggest economy in the world, with gross GDP of $22,996 billion in 2021, followed by China, catching up fast, at €17,734 billion (with Japan, Germany, and the UK a long way behind). [33] In terms of military spending, the lead of the US is even greater. In 2021, its military budget stood at $801 billion, more than the next nine countries (China, India, the UK, Russia, France, Germany, Saudi Arabia, Japan, and South Korea) combined. [34] But when it comes to the UN Human Development Index (HDI), a statistical composite index of life expectancy, education, and per capita income, the US stands in only twenty-first place, way below Ireland in eighth and even South Korea in nineteenth place. [35]

According to UNICEF, US infant mortality in 2020 stood at 5.4 per 1000 live births, compared to the UK at 3.6, France at 3.4, Germany at 3.1, Ireland at 2.6, and Norway at only 1.7. [36] And in terms of life expectancy, the US, at an average of 79.11 years, stands in a scandalous forty-sixth place behind countries such as Costa Rica, Chile, Cuba, and even Puerto Rico. [37]

In short, the US, which holds the greatest absolute accumulation of wealth and of armaments in the history of the world, is a disaster when it comes to the welfare of its own people, and it is getting worse. In August 2022 it was announced that

life expectancy in the U.S. declined again in 2021, after a historic drop in 2020, to reach the lowest point in decades. In 2021, the average American could expect to live until age 76, which fell from 77 in 2020 and 79 in 2019. That marks the lowest age since 1996 and the largest 2-year decline since 1923. [38]

But the US is just the lead example of what is a general and global trend. On September 8th, the United Nations issued its latest Human Development Index Report which records that:

For the first time in the 32 years that the UN Development Programme (UNDP) has been calculating it, the Human Development Index, which measures a nation’s health, education, and standard of living, has declined globally for two years in a row.

This signals a deepening crisis for many regions, and Latin America, the Caribbean, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia have been hit particularly hard. [39]

The foreword to the report states:

We are living in uncertain times. The Covid-19 pandemic, now in its third year, continues to spin off new variants. The war in Ukraine reverberates throughout the world, causing immense human suffering, including a cost-of-living crisis. Climate and ecological disasters threaten the world daily. It is seductively easy to discount crises as one-offs, natural to hope for a return to normal. But dousing the latest fire or booting the latest demagogue will be an unwinnable game of whack-a-mole unless we come to grips with the fact that the world is fundamentally changing. There is no going back. Layers of uncertainty are stacking up and interacting to unsettle our lives in unprecedented ways. People have faced diseases, wars and environmental disruptions before. But the confluence of destabilizing planetary pressures with growing inequalities, sweeping societal transformations to ease those pressures and widespread polarization present new, complex, interacting sources of uncertainty for the world and everyone in it. That is the new normal. [40]

In one respect, Marx’s diagnosis of the contradiction between the forces and relations of production should be modified. He speaks of the relations of production as a ‘fetter’ on the development of the forces of production. This fitted very well for the transition from feudalism to capitalism, but more important today is the distortion and perversion of the productive forces into forces that are alien and hostile to humanity, that are turned against their makers. This also was anticipated by Marx. In his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 he argued that capitalism rested on alienated labour (i.e., labour not owned or controlled by the worker but sold to the capitalist) and as a consequence, the object which labour produces – labour’s product – confronts it as something alien, as a power independent of the producer ...

The alienation of the worker in his product means not only that his labour becomes an object, an external existence, but that it exists outside him, independently, as something alien to him, and that it becomes a power on its own confronting him. It means that the life which he has conferred on the object confronts him as something hostile and alien.

Nuclear war and catastrophic climate change are two extreme examples of humanity being dominated, threatened, and perhaps ultimately destroyed, literally by the ‘hostile and alien’ products of our own labour. [41]

We have said more than enough to indicate the scale and depth of the present crisis, but how will it develop in the future? Antonio Gramsci issued a salutary warning regarding attempts to predict the future.

In reality one can ‘scientifically’ foresee only the struggle, but not the concrete moments of the struggle, which cannot but be the results of opposing forces in continuous movement, which are never reducible fixed quantities since within them quantity is continually becoming quality. [42]

Manifestly, the global crisis is one in which there are ‘opposing forces in continuous movement.’ Will the standard neo-liberal response of raising interest rates squeeze inflation out of the system as it did with the Volcker Shock of 1980, and will this provoke a new recession, as seems very likely? Or will we face the combination of inflation and repression? If there is a new recession, how long will it last? Will capitalism, at least temporarily, revive? Will there be another surge of Covid-19, or will a new, more deadly virus emerge? And what would be the economic consequences of another pandemic? Will the war in Ukraine grind on indefinitely or will it escalate further? Could there be some kind of peace deal, albeit a rotten one? And if there is such a peace, how long before the underlying rivalry between the US and China erupts in conflict in the South China Sea or over Taiwan?

The answers to these questions are, I think, imponderable. But there are some things we can say with confidence: on the economic front there will be no return to stable prosperity or steady growth in the system’s core countries; and with the greatest certainty that, without a major change in direction (of which there is no sign), climate change and the wider environmental crisis will escalate with immense economic, social, and political consequences over the next decade. With equal certainty we can say that we are looking at an era of intense political turmoil.

One of the most important features of political life in recent decades, especially since the 2008 crash, has been the erosion and decline of the mainstream so-called moderate centre. In Ireland, Fianna Fail, for long the dominant party in the state, has shrunk to the point where it is stuck in the mid-teens in the opinion polls. Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, one or other of whom won every general election since 1927, were forced in 2020 into coalition with each other (and the Greens) in order to cling to power, and found that even together they are matched by Sinn Féin. In the US, still the most influential country in the world politically, we have seen ‘mainstream’ Republicanism devoured by Trumpism, even after the debacle of January 6th, 2021, and a serious challenge to centrist Democrats from Bernie Sanders, AOC, and the like. The US is now a society in which an internet awash with far-right and fascist conspiracy theories exists alongside the biggest street mobilizations in the country’s history for Black Lives Matter, and as I write these lines, thousands of school students in Virginia are walking out of schools in support of their transgender schoolmates.

In Sweden, the classical land of social democracy, the Social Democrat vote has fallen from 50.1 percent in 1968 to 28.3 percent in 2018 and 30.3 percent30.3 percent in 2022. Significantly, in 2002 50 percent of blue-collar workers still voted Social Democrat: by 2022 that had fallen to 32 percent. [43] In contrast, the far-right Swedish Democrats have risen from 0.1 percent in 1991, to 5.7 percent in 2010, to 20.5 percent in 2022. [44] In the first round of the French Presidential Election earlier this year, the far-right Marine le Pen came second with 23.15 percent (to Macron’s 27.85 percent), with the radical-left Melenchon on 21.95 percent but the once mighty Communist Party (PCF) languishing on 2.28 percent and the Socialist Party of François Mitterrand and François Hollande reduced to only 1.75 percent. [45] In Italy, what was once the largest political party of any kind in Europe, the Italian Communist Party (PCI), ceased to exist in 1991. Its moderate centre-left replacement polled percent 19.07 percent in 2022 (as part of a motley ‘left-of-centre’ coalition which got 26.13 percent). But the far-right Brothers of Italy, founded in 2012, has rocketed upwards from only 2 percent in 2013 and 4.4 percent in 2018 to victory with 26 percent (as leading party of a right-wing coalition with 43.79 percent). [46] Nor is this kind of development restricted to Europe. In India, Congress, the traditional party of the Indian bourgeoisie, which ruled almost continuously from 1947 to 1991 and regularly polled votes in the forties, crashed to 19.3 percent in 2014 and 19.5 percent in 2019. [47] The far right BJP (a Hindutva, anti-Muslim Hindu-supremacist party), however, leapt from 18.9 percent in 2009 to 31.3 percent in 2014, and has now reached 37.4 percent. [48]

These are just snapshots, and are far from presenting a rounded or complete picture. The overall situation is extremely complicated, mixed, and uneven. In Germany, the far-right AfD have so far been held at bay with 10.3 percent in 2021, and an increase for the SPD to 25.7 percent. [49] In the UK, the Tory Party has been captured (under Johnson and Truss) by the Brexit Right, but the outright far right and fascists have been marginalised and the Truss Government is in meltdown as I write, with Starmer’s right-wing flag waving Labour seventeen points ahead in the polls. [50] (The previous line was written on the morning of September 29th. By the afternoon there was a new opinion poll showing Labour a record thirty-four points ahead!) In Ireland, the far right seem confined to the ranks of the lost and bewildered. Nevertheless, some limited generalisations are possible.

First, the political situation is very fluid and volatile; old loyalties are breaking down and ‘all that is solid is busy melting into air.’ Parties can move from the margins to centre stage very rapidly. The dramatic successes of the far right are predicated above all on the repeated failures of mainstream politics, including and especially of social democracy, to deliver anything, not even much in the way of protection, for working-class people. Business-as-usual simply isn’t working, and where anger and bitterness remains unsatisfied, they seek expression elsewhere. Also a factor in this situation is the failure of the far left, of real socialists and revolutionaries, even to register as players in the consciousness of most working people in most countries (Ireland is an exception here), and I will return to this in a moment. The only thing that prevents the present political conjuncture being utterly catastrophic is that on their journey towards office, parties such as the Swedish Democrats and Brothers of Italy – and the same applies to Marine le Pen and National Rally – have tried to distance themselves from their fascist roots. As a result, they do not have the street-fighting forces needed (and possessed by both Mussolini and Hitler) to suppress bourgeois democracy, smash the trade unions and the left, and install fascist dictatorships. There is no justification for complacency in this, but it does give the left the time and the opportunity to heed the deadly warnings that are being given and mount a serious challenge to the system.

This, of course, is easier said than done. The inability of reformist social democracy (including in its Eurocommunist form) to resolve any of the multiple crises engulfing capitalism in decay is, I believe, inherent and incurable. It lacks either the political will or the political means to overcome the resistance of the forces of capital and the capitalist state to any attempt at even serious reform. The left reformist strategy has been subject to two major tests in the last decade: the Syriza government in Greece and the Corbyn moment in the British Labour Party. In the Syriza case, the party leadership simply capitulated in the face of economic pressure from the European Central Bank, the EU, and the IMF, and was allowed to do so by the majority of the party. In the case of Corbyn, the majority of the Parliamentary Labour Party twice undermined his attempts to win general elections and collaborated with the media (and Zionist and state forces) to destroy his leadership and the left as a whole. In both examples, reformist leaderships crumbled even before any decisive battle with the system was joined. The notion that they would have held firm in a real confrontation is entirely fanciful. Moreover, these failures were repetitions of failures that go back a century through Chile in 1973, the Popular Fronts in the thirties, to German Social Democracy in the Weimar Republic. [51] Interestingly, the notion put forward by Podemos in the Spanish state that it could transcend the division between left and right and the debate between reform and revolution through some form of intellectual gymnastics simply evaporated into thin air with the passing of time as it settled down into being another centre-left reformist formation. This does not mean socialists should not campaign for and support left parties and left governments against the right, but this is not enough to produce a fundamental solution.

But what of the revolutionary socialist left? Internationally, the main problem of the real Marxist and socialist left is that it is small and isolated from the working class. This rift with the mass of the working class developed originally for historical reasons. It was produced by the great historical defeats of the fascist and Stalinist counter-revolutions of the 1920s and ’30s. But prolonged isolation also damaged the revolutionaries and produced all sorts of sectarian habits and practices through decades in which small groups got accustomed to speaking mainly to themselves and like-minded individuals. In the current historic crisis of the system, it is a matter of urgency that these habits be overcome.

Concretely, this means taking the risks necessary to break out of small-circle politics and relate to the working class as it is today. This does not mean making concessions to racism, sexism, homophobia, or transphobia, but it does mean championing what working-class people need and are actually fighting for, not attempting to impose ready-made schemas or programmes. [52]

This is not a question, as is sometimes supposed, of counterposing ‘economic’ class politics to identity politics or environmentalism. The working class today is enormously more internationalised, multi-ethnic, feminised, and generally diverse than was the case a generation or so ago. No workers’ movement, no mass strike movement, today can fail to combat oppression without destroying its own unity: it is a necessary part of the working class reconstituting itself as a fighting force. It doesn’t mean shying away from the climate crisis on the basis of narrow trade and national protectionism. Vast swathes of the working class internationally are already, and are destined to be in the near future, immediate victims of climate change. The cause of a just transition is the cause of labour, to echo James Connolly. [53] We must bring climate struggles and workers’ struggles together, and there are welcome signs that this may be happening, for example with climate activists and unions combining to demand climate justice and support picket lines and cost-of-living mobilisations.

What it means is understanding that if, in a desperate cost-of-living crisis or indeed a recession or other crises facing the class, we do not step forward with demands and actions that articulate the anger of the mass of working people, we leave the door open to the right. This in turn requires a willingness to learn how to work together in united fronts or other formations with people with whom we have only partial agreement and sometimes substantial disagreements. It is past failures of the far left (not only of the Stalinists and the reformists) that created in Italy the vacuum into which Giorgia Meloni and the Brothers of Italy stepped. And it means grasping that industrial and street mobilization needs to be complemented, as part of the struggle for the political consciousness of the working class, with serious electoral invention. [54] Again, vacating this space gifts it to the right.

The points made here about the revolutionary left are a compressed version of an argument I have made elsewhere at much greater length. [55] They also approximate broadly the project we have made a modest start on with People Before Profit. [56] My view is that they have a certain general validity. In an inverse way, the rapid rise of the Swedish Democrats and the Brothers of Italy shows, as did the spectacular rise of Corbyn, what can be achieved by the far left in the conditions of today, provided we are ‘at the races’ (i.e., a factor in the consciousness of wide layers of the working class). At any rate, with capitalism in serious decay, the basic problem of overcoming the rift between socialists and the working class is a vital necessity if we are to avoid the dreadful fate of fascist barbarism and seize the real opportunities available to us.

1. All these figures are taken from https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/inflation-rate. It should also be said that all these figures are changing continually and are bound to be different by the time this article is printed or read.

2. https://kraneshares.com/climate-change-is-a-growing-and-persistent-driver-of-inflation/.

3. See https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/aug/02/bp-profits-oil-prices-ukraine-war-energy-prices-cost-of-living-crisis.

4. https://www.shell.com/investors/results-and-reporting/quarterly-results/2022/q2-2022/_jcr_content/root/main/section/simple/simple/call_to_action_copy/links/item0.stream/1662989240428/ea8d3faec80bcc2622226933fa722b4955a5e83a/q2-2022-quarterly-press-release.pdf.

5. https://corporate.exxonmobil.com/news/newsroom/news-releases/2022/0729_exxonmobil-announces-second-quarter-2022%20results#.

6. Michael Roberts, The Long Depression: Marxism and the Global Crisis of Capitalism, London 2016.

7. ‘Eamonn Ryan ... said it was “vital” the projects were developed to offset the power supply crisis facing this country. It has now emerged that some of the plants may not go ahead. Industry sources have told the Business Post that the projects are no longer economically viable due to rising cost inflation.’ Business Post, 9-10 October, 2022.

8. See Kieran Allen, The politics of inflation, IMR, 33. p. 6.

9. In Iran, of course, the issue of the enforced hijab and the oppression of women was central to the revolt, along with the overall tyrannical nature of the regime, but the economic crisis contributes to the mass discontent and the popularity of the rebellion.

10. https://tradingeconomics.com/sri-lanka/inflation-cpi.

11. https://tradingeconomics.com/iran/indicators.

12. See Chris Harman, The Lost Revolution: Germany 1918–1923, London 1982.

13. See the account in Kieran Allen, as above.

14. https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/fed-seen-driving-interest-rates-higher-inflation-sears-2022-10-13/.

15. New estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO) show that the full death toll associated directly or indirectly with the Covid-19 pandemic (described as “excess mortality”) between January 1st, 2020, and December 31st, 2021, was approximately 14.9 million (range 13.3 million to 16.6 million).

16. https://ourworldindata.org/excess-mortality-covid#estimated-excess-mortality-from-the-economist.

17. Lee Humber, What makes a disease go viral?, Socialist Review, 455, March 2020, https://socialistworker.co.uk/socialist-review-archive/what-makes-disease-go-viral/.

18. [No note in printed edition].

19. https://thebulletin.org/2022/03/bulletin-science-and-security-board-condemns-russian-invasion-of-ukraine-doomsday-clock-stays-at-100-seconds-to-midnight/.

20. See, for example, the various estimates here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2022_Russian_invasion_of_Ukraine#Casualties.

21. See statistics here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2022_Russian_invasion_of_Ukraine#Refugee_crisis.

22. Rob Wallace, Big Farms Make Big Flu, p. 280.

23. https://www.world-grain.com/articles/16997-ukraine-grain-exports-reach-472-million-tonnes-so-far-for-2021-22.

24. John Molyneux, Lenin for Today, London 1917, pp. 14–15.

25. On October 14th, the World Wildlife Fund issued a ‘devastating’ report recording a 69 percent decline in the global world wildlife population since 1970. https://www.rte.ie/news/newslens/2022/1014/1329197-living-planet-report/.

26. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2021_European_floods.

27. https://floodlist.com/africa.

28. https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidbressan/2022/06/05/carbon-dioxide-peaked-in-2022-at-levels-not-seen-for-millions-of-years/#:~:text=%5B%2B%5D&text=NOAA-,Carbon%20dioxide%20measured%20at%20NOAA's%20Mauna%20Loa%20Atmospheric%20Baseline%20Observatory,seen%20for%20millions%20of%20years.

29. See, for example, Mark Walsh, Intellectual Property, Patents and the Pandemic, IMR, 32: http://www.irishmarxistreview.net/index.php/imr/article/view/450 and Sean Mitchell, Last Exit to Socialism?, IMR, 27: http://www.irishmarxistreview.net/index.php/imr/article/view/371.

30. www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1859/critique-pol-economy/preface.htm.

31. See the discussion and data in Ian Angus, Facing the Anthropocene, New York 2014, especially pp. 38–58.

32. This does not mean Ireland’s people are the third-richest in the world, as GDP per capita figures are greatly inflated by the fact that Ireland functions as a tax haven.

33. https://www.worlddata.info/largest-economies.php#:~:text=With%20a%20GDP%20of%2023.0,ninth%20place%20in%20this%20ranking.

34. Figures from the Stockholm Peace Research Institute: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_military_expenditures.

35. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_Development_Index#2021_Human_Development_Index_(2022report).

36. https://data.unicef.org/resources/data_explorer/unicef_f/?ag=UNICEF&df=GLOBAL_DATAFLOW.

37. https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/life-expectancy/.

38. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2022/20220831.htm.

39. https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/09/1126121.

40. https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2021-22pdf_1.pdf.

41. www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/manuscripts/labour.htm.

42. Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, London 1971, p. 438.

43. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swedish_Social_Democratic_Party#Statistical_changes_in_voter_base.

44. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sweden_Democrats#2022_election_(2022–.

45. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2022_French_presidential_election#First_round.

46. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2022_Italian_general_election#Results.

47. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_National_Congress#General_Election_Results.

48. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bharatiya_Janata_Party#General_election_results.

49. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2021_German_federal_election

50. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opinion_polling_for_the_next_United_Kingdom_general_election#2022.

51. For a fuller analysis, see John Molyneux, Understanding Left Reformism, IMR, 6.

52. It is worth remembering that this is just a paraphrase of what Marx said in The Communist Manifesto. ‘[Communists] have no interests separate and apart from those of the proletariat as a whole ... They do not set up any sectarian principles of their own, by which to shape and mould the proletarian movement. The theoretical conclusions of the Communists are in no way based on ideas or principles that have been invented, or discovered, by this or that would-be universal reformer. They merely express, in general terms, actual relations springing from an existing class struggle, from a historical movement going on under our very eyes.’

53. ‘The cause of Ireland is the cause of labour.’

54. It probably needs to be said again that this not some sort of electoralist or reformist deviation but orthodox Leninism. See Lenin, Left-Wing Communism: an Infantile Disorder.

55. See John Molyneux, Socialism and the Working Class Today, in John Molyneux, Selected Writings on Socialism and Revolution, London 2022, pp. 41–72.

56. See John Molyneux, What is People Before Profit?, IMR, 32: http://www.irishmarxistreview.net/index.php/imr/article/view/448.

John Molyneux Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 2 January 2023