Introduction to

The New Review

(1913 — 1916)

Throughout its early history, the American radical movement was marked by a certain dualism between the country’s two urban centers — New York and Chicago. Socialist, Anarchist, and Syndicalist groups emerged and developed in each of these cities, often with a certain competitive tension felt towards their comrades in the opposite metropolis. Some of the rampant factionalism of American radicalism makes best sense when seen through this prism — rough and tumble Chicago versus erudite New York.

Following the ouster of the fastidious A.M. Simons as editor of the Chicago monthly International Socialist Review in 1908, publisher Charles H. Kerr and chief editor Mary Marcy moved the magazine leftward ho, shortening the length of articles, simplifying the prose, and adding photographs of people engaged in The Struggle. The new ISR was open in its embrace of the controversial and rowdy anti-capitalist activities of the Industrial Workers of the World. It was not shy in pushing the sometimes staid Socialist party of America toward greater militance. The magazine, now glossy and accessible, quickly emerged as the publication of record of advocates of revolutionary industrial unionism in America.

But the International Socialist Review was, after all, a Chicago magazine — unwashed and boisterous. The Socialists of New York City felt a continued need for a theoretical magazine closer to them in temperament, more reflective of their more cosmopolitan concerns.

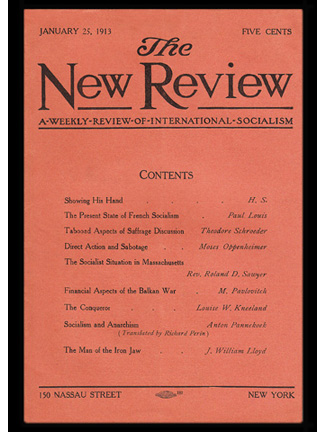

So in January 1913 a new publication was born — The New Review

The lead editorial in the magazine’s debut issue took a subtle jab at the post-1908 nature of Charles Kerr’s magazine, declaring it would be “devoted to education, rather than agitation” and intended to instill “a better knowledge and clearer understanding of the theories and principles, history and methods of the International Socialist Movement.” The new journal declared its purpose to make known “the intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors” to the “awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation.” In practice, it proved to be a theoretical magazine by intellectuals, for intellectuals. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

Never intending to be ideologically homogeneous, the trend of The New Review over the three-and-a-half years of its existence was from Center to Left. The magazine was active in attempting to make sense of the hot button issues of syndicalism and mass action in 1913, maintaining a sympathetic posture. It provided a forum for the writing of two of the principals of left wing New York literary-artistic magazine The Masses, Max Eastman and Floyd Dell. It dealt extensively with the issues of feminism, American intervention in Mexico, the growth of militarism, and the role of the International Socialist movement in the war.

Over time the wunderkind of American radicalism, Louis C. Fraina, came to play an increasing role in the magazine, helping move it on its generally leftward path. Other editorial contributors of note over the publication’s history included Herman Simpson, Louis B. Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, William E. Bohn, Frank Bohn, and Isaac Hourwich.

The June 1916 issue proved the be the publication’s last. Lack of money, as always, proved terminal.

Tim Davenport

Corvallis, OR

August 2011

Special Note of thanks to the following individuals and institutions that made copies of The New Review available and help scan and process them for this archive: Dr. Marty Goodman and Robin Palmer of the The Riazanov Project and David Walters from the Marxists Internet Archive.

The New Review, Volume 1, 1913

The New Review, Volume 2, 1914

The New Review, Volume 3, 1915

The New Review, Volume 4, 1916