I think it fair to say that the impression conveyed by Amnesty International reports on Albania is that the country is a vast prison camp.

I think it fair to say that the impression conveyed by Amnesty International reports on Albania is that the country is a vast prison camp.

Source: Albanian Life, No. 38/No. 1, 1987

Transcription/Markup: The American Party of Labor, 2018

Public Domain: Marxists Internet Archive (2018). You may freely copy, distribute, display and perform this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit “Marxists Internet Archive” as your source.

I think it fair to say that the impression conveyed by Amnesty International reports on Albania is that the country is a vast prison camp.

I think it fair to say that the impression conveyed by Amnesty International reports on Albania is that the country is a vast prison camp.

But if one goes to Albania, one finds a radically different picture. One finds a country where malarial marshes have been drained and transformed into fertile land, where barren hills have been transformed into terraces of citrus fruits. One finds a country where railways, power stations and modern industrial complexes are being built, so that industrial production is today 164 times the level of 1938.

Nor does the lion's share of this rapidly growing wealth go to some privileged class or bureaucratic elite. For Albania is unique in many respects - not least in the fact that differential incomes are limited by law to a maximum of 2:1 - a figure which may be compared with current figures in Britain of 6,000:1 - making it the most equalitarian society in the world. There is no unemployment, and the right to work and to choose one's occupation is written into the Constit ution and applied in practice. There is no inflation - the prices of consumer goods consistently fall as pro duction rises - and the citizen pays no rates or taxes. There is a free and non-contributory health service, and pensions - fixed at 70% of retiring pay - are also non-contributory and are payable as young as 50 in certain occupations considered especially arduous. More than 80% of the population live in, dwellings built since Liberation in 1944, and rents are fixed at approximately 3% of a single wage. As a result of these achievements, average expectation of life has been raised from 38 years in 1938 to 70 today. And in the field of culture, there can be few countries with a population of only three million which support seven symphony orchestras.

Clearly, this is not a society - as Amnesty International reports appear to suggest - which cares little for humanity.

True, Albanians regard with great scepticism much of the talk about "human rights" which emanates from Western politicians. As an Albanian worker remarked to me on my last visit: "When Reagan and Thatcher prattle about 'human rights', it usually means they are about to drop bombs on women and children somewhere!" Indeed, Peter Benenson, the founding father of Amnesty International, recently expressed regret in The Observer that the expression "human rights" had become "a weapon in the cold war". I cannot, of course, speak for the Albanian government or the Albanian people. But I have no doubt that most Albanians recognise the value of much of the work carried out by Amnesty International in exposing what they accept as true violations of human rights in various countries of the world. At the same time, they could, I feel, be forgiven if they have the impression that the members of Amnesty International are largely comfortably-off intellectuals who see human rights mainly in terms of freedom of expression. "What human rights", an Albanian could ask, "does an unemployed black teenager living in a slum ghetto in Liverpool, have?" Yet one finds no mention of such things in Amnesty International reports.

It is also, in my view, very understandable that Albanians should feel that the leadership of Amnesty International, if not itself politically prejudiced, is so concerned to appear politically "neutral" that it feels compelled to present the left-wing regime in Albania, irrespective of facts, in the same unfavour able terms as it correctly- portrays right-wing repressive dictatorships such as those of Chile and South Africa.

Indeed, Albanians could justifiably cite many examples of this lack of objectivity. For example, Amnesty International makes much of the fact that the death penalty is retained in Albania as a non obligator y "temporary and extraordinary" penal measure for certain crimes considered exceptionally socially dangerous. Amnesty International is, of course, entitled to hold the view that the death penalty is unjustified in all circumstances. Yet if one turns to the British section of Amnesty International's last annual report, one finds no mention of the fact that the death penalty is retained in Britain for certain offences, and is even retained for murder in part of the United Kingdom.

Again, Albanians could point out that Amnesty International claims to base its principles on the United Nations international covenants on human rights. Article 6 of the UN Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights lays down the right to work as one of the fundamental human rights. Yet the British section of Amnesty International's 1985 report makes no mention of the fact that this right is denied to some four million British citizens.

If you ask an Albanian constitutional lawyer whether he would not prefer to live under "democracy" such as we have in Britain, he could well raise an eyerbrow and ask: "What democracy?"

"Your head of state", he might say, "is a hereditary monarch; ours is an elected President. Your elected chamber is constrained by a non-elected upper house, which can hold up legislation; we have a single, directly-elected chamber, the People's Assembly. Your hereditary monarch has the constitutional power to veto legislation; our elected President does not. Your Prime Minister is appointed by the monarch, and selects his or her Ministers; all our Ministers are elected by the People's Assembly. Your MPs can be elected on a minority vote; our deputies cannot. Your electors have no power to choose who shall be their candidate, only to vote for a party nominee; our electors choose their candidate by a democratic pre-election process. Your elected MPs can cross the floor of the House to another party the day after the election, and there is nothing the electors can do about it for five years; our electors can recall their deputy by a simple petition if he or she fails to live up to expectations. Your judges are appointed from above; ours are directly elected. Your judges can make law; in Albania we have no such thing as case law…"

Albanians are normally very polite to questioning visitors, but our Albanian lawyer might well ask: "What gives you the right to come here and lecture us on democracy?"

If you go on to say: "But at least our electors can choose between several parties", our Albanian lawyer might well reply "Your leading jurist Walter Bagehot, like the American Abbot Lowell, has pointed out that parliamentary pluralism can function only when all the parties capable of forming a government are agreed on fundamental social principles. Here in Albania we have transformed society from the roots, abolishing all profit-making private enterprise and establishing a fully-planned socialist economy, geared to maximising the welfare of the people. You could not have pluralist parliamentarism, with its "loyal opposition", in such circumstances and having brought about a revolutionary change which has transformed society to their great advantage, our people are not prepared to allow a counter-revolutionary party to operate. Our Party of Labour is not a political party in your sense. It is an organisation of those who have proved themselves to be the most sincere, the most active, the most dedicated socialists. Building socialism cannot be a spontaneous process; it requires scientific leadership. Our party has no legislative power; it operates as an organisation of leadership which can function only by persuasion. The confidence of our working people in this leadership rests on its achievements in their interests. But, of course, candidates for office may or may not be members of the Party. Democracy means "government by the common people", and this is what we assuredly have in Albania. We don't measure democracy by the number of parties that exist".

And if you say: "But in Albania anti-socialist propaganda is illegal; in Britain we have complete freedom of expression", our Albanian lawyer might well say: "You mean, provided you don't infringe the Trades Description Act; the Official Secrets Act; the Race Relations Act; the laws on blasphemy, obscenity, sedition, contempt of court, contempt of parliament and insulting words and behaviour; or a court injunction". And he may go on to point out that restrictions on freedom of expression are endorsed by the United Nations Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Article 5 of which states:

"Nothing in the present Covenant may be interpreted as implying for any . . group of person any right to engage in any activity…aimed at the - destruction of any of the rights or freedoms recognised herein".

But Article 6, of the Covenant, as has been said, recognises the right to work as a fundamental human right, and Albanians agree. And so our Albanian lawyer will argue that to campaign for the restoration of capitalism, for the return of employers with the right to hire and fire workers according to the ^demands of the profit motive is to campaign, in fact, against the right of all to work, so that the Albanian restriction on anti-socialist political activity is in defence of human rights.

It should be noted that this restriction in no way means restriction of criticism of official actions. Every town and village has its public notice-board on which citizens may - and do - put up complaints, which must be officially replied to within a few days.

Amnesty International is critical of the fact that religious propaganda and activity are prohibited by law in Albania. But Article 18 of the United Nations Covenant on Civil and Political Rights lays down that freedom of religion may be subject to

" … such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary to protect … morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others".

And so our Albanian lawyer may quote to you the Christian Beatitudes:

"Blessed are the meek…

Blessed are the poor in spirit".

"This is the morality", he will argue, "not of free people, but of slaves - which is no doubt why Constantine made Christianity the official religion of the slave-owning Roman Empire".

And, since Islam was formerly the dominant religion in Albania, he may quote to you the Koran:

"Men are the managers of the affairs of women.

Righteous women are therefore obedient.

And those you fear may be rebellious: banish them to their couches and beat them".

"So", our Albanian lawyer may insist, "to permit such teachings under the pretence that they are divinely inspired, would be in breach of morality and of the human rights of half the population. Our restrictions on religion are therefore in defence of human rights".

It may be mentioned, however, that no lay person has ever been prosecuted under the law banning religious propaganda.

Amnesty International is also concerned at the fact that, to travel abroad, an Albanian citizen must obtain an exit visa. This is not because the Albanian authorities believe that masses of Albanians would like to come and live in the "West". Emigration in search of work was, in fact, one of the major curses of pre-war Albania. Hundreds of ordinary Albanians do go abroad each year as members of amateur cultural groups, while the health service provides free treatment abroad for the decreasing number of cases where this cannot yet be provided within the country. And I must say that most Albanians I have met working abroad are only too nostalgic for their motherland.

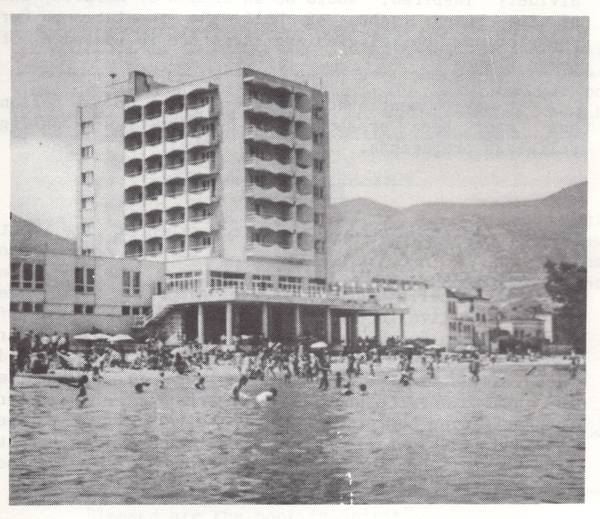

But freedom to go abroad is empty unless it carries with it the right to foreign currency. This is limited, and its use - for example, for buying imports to further Albania's vast programme of economic devel opment - forms part of the state plan. Thus foreign currency is allocated according to national need, and holidays abroad are not regarded as a first priority in the state plan. I must say, however, that I have never met an Albanian who felt deprived of his human rights by the fact that he was compelled to spend his holidays, subsidised by his trade union, in the sun of the Albanian Riviera instead of wandering round Lowestoft in the rain trying to find a hotel receptionist who spoke Albanian. Of course, if our government could be persuaded to return to Albania her looted gold reserve, which has lain in the vaults of the Bank of England for the last forty years, this would ease the country's foreign exchange problems to some extent.

|

This is a very popular resort in summer, being much cooler than the coast. Enver Hoxha passed many holidays here. Trade unions run subsidsised holiday hotels here for their members, as they do throughout Albania. Children usually spend their summer holidays in Pioneer Camps, which are also heavily subsidised and are to be found along the coast and in the mountains. |

So far I have dealt with aspects of Amnesty International reports which are factual, but on the inter pretation of which the Albanian authorities - and most Albanian citizens - would disagree. I want to conclude by dealing with aspects which Albanians would agree were violations of human rights, but which they emphatically deny take place in Albania.

Firstly, Amnesty International reports charge that defendants in criminal cases in Albania do not receive a fair trial.

Far from being a police state, however, one sees very few police in Albania, there are no moves to arm them with water cannon and CS gas, and relations between the police and the public are very different to those that exist in Britain, where an increasing section of the population has come to regard them as formed predominantly of racist thugs who constitute the employers' private army.

Indeed, Albania is unique in that its police have no power of arrest, nor do they investigate alleged crimes. The amount of crime is very small indeed, and the Albanian authorities attribute this to the elimination of many of the social causes of crime which exist in other countries.

An apparent crime is investigated-by an investigator of the Ministry of Internal Affairs - the nearest equivalent to which is, perhaps, a French examining magistrate. His task is to ascertain if a crime has been committed and, if so, whether the evidence establishes beyond doubt that it has been committed by a certain person. If the answer to either of these questions is "no", the case is halted. If the answer to both is "yes", then the investigator may charge the person concerned and send the case to court for trial. The number of criminal cases going to court averages just over 100 a year, and there is nothing sinister in the fact that most defendants are found guilty. The investigator's instructions are that if there is the slightest doubt concerning the guilt of a person, the case shall be halted before going to court. And it must be noted that a mere technical breach of the penal code is not a crime; to become so, the social harmfulness of the act committed must be established.

An Albanian court consists of one professional judge, and two so-called assistant judges drawn from a panel of ordinary citizens. All decisions are by majority vote, so that the two assistant judges may - and sometimes do - outvote the professional judge.

All trials are held in public, except where state secrets or intimate sexual matters are involved. Every defendant is entitled to have an adviser to sit with him, but it is only obligatory in certain cases (for example, where the defendant is under 18 years of age) for this to be a lawyer. In other cases, this is at the discretion of the court. In all cases where a defence lawyer acts, no legal fees are payable by the defendant.

The principal difference between procedure in British and Albanian criminal courts, apart from the greater informality of the latter, lies in the fact that Albanian courts reject the adversarial system. The official view is that it is the task of the court to ascertain the truth, and that it is as important for no person guilty of a crime to escape conviction as for no innocent person to be convicted. Indeed, it is held that the conviction and reeducation of a criminal is not merely in the interests of society, but in the interests of the criminal himself. They thus reject the adversarial system as not the best way of ascertaining the truth, since under this system a guilty person may employ - if he has the money - a brilliant barrister to try to convince the court, falsely, of his client's innocence.

The Albanian authorities therefore maintain that their system of justice is incomparably fairer and more just than the adversarial system, and can indeed point to numerous examples of admitted miscarriages of justice in other countries which have resulted from the latter system.

Secondly, in its 1984 report on Albania, Amnesty Inter national gives a vague estimate, based on the statements of political émigrés, of "several thousand" persons serving sentences of deprivation of liberty for political crimes.

When I visited Amnesty International headquarters by invitation in early 1983, I discussed with the young woman in charge of Albanian affairs the official figures of political detainees issued by the Albanian leader Enver Hoxha in November 1982, in response to the propaganda then being circulated by the government of Greece - figures which worked out to a total of just over 200. Yet when the report on Albania was published more than a year later it contained the statement on page 36 that there was "a lack of any official figures" on the number of political detainees. This statement was not only untrue, but was known by the leadership of Amnesty International to be untrue more than a year before the report was published.

Thirdly, and finally, I come to the allegations of torture and ill-treatment of detainees which make up a large part of the 1984 report on Albania…"

From discussions with Albanians concerned with the penal system at levels up to that of judge of the Supreme Court, and from translating the materials used in their training, I am completely satisfied that the whole aim of the Albanian penal system is to transform anti-social offenders into useful members of society. It is clear that the slightest affront to the dignity of a prisoner - let alone his ill-treatment - runs directly counter to this aim, and that is why it is subject to the most severe penalties.

Albanian detainees have the right not only to family visits, but to address letters of complaint to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which must investigate such complaints immediately. The great majority of political detainees are confined in work camps - there are only two small prisons in the country - and they enjoy regular conjugal visits in order that family life may be disrupted as little as possible. Further more, a judge who has sentenced a defendant to deprivation of liberty must visit his "patient" (the official term) regularly to ascertain his progress, and may remit the rest of the detainee's sentence when he considers this to be no longer necessary. It is not without interest that, of the nine "case histories" published in the Amnesty International report on Albania, seven narrators state that they were released prior to the expiry of their sentences.

Ethical education - designed to inculcate the attitude that the individual should gain his happiness by working for the happiness of his fellow human beings -is a feature of Albanian society, from the nursery school onward. In the case of a criminal, it is clear that normal ethical education has failed and the purpose of a penal measure such as deprivation of liberty is to create the most effective special conditions in which ethical reeducation may be successful.

In countries where a privileged minority rule over and exploit the majority, their rule cannot be defended by reason. Consequently terror - the instillation of fear - is an essential part of the penal system of such a society, because "re-education" of the offender to the social justice of the society is logically impossible. But the Albanian authorities maintain that socialist society is so inherently just that it is relatively easy in most cases to reeducate the offender to a true ethical outlook.

The allegations of the "ill-treatment" of prisoners published in the report come from persons claiming to be ex-prisoners, and the report admits (on page 4) that their statements

"...undoubtedly sometimes contain inaccuracies and may be suspected of bias".

It must be remembered that, to the extent that the narrators are genuine emigres from Albania - and in some cases their stories cast doubt even on this - they arrive abroad in most cases without funds. Many of the allegations made in the Amnesty International report have already been published in the press, which will generally pay well for any "horror story" about Albania, true or false.

Such allegations become evidence only if the author is prepared to submit himself to cross- examination with the aim of testing his truthfulness. The Albanian Society requested Amnesty International for facilities for an objective expert to interview its witnesses with this aim, but the request was refused.

The young woman in charge of Albanian affairs made it clear to me that she did not understand the Albanian language, and was dependent upon, emigres - almost without exception politically hostile to the post-war socialist regime - for most of her information about Albania. Indeed, relations with these emigres were so close that Amnesty International admitted to me in a letter dated 11 June 1982 that "special permission" had been granted to Anton Logoreci to have access to a report of one émigré which was too confidential for anyone else to be allowed to see. Logoreci, who had been private secretary to Sir Jocelyn Percy, the British officer in charge of Zog's notoriously repressive gendarmerie, was also permitted to use this otherwise secret report in a book which constituted a vitriolic political diatribe against the People's Socialist Republic of Albania.

When the Greek Alternate Minister for Foreign Affairs, Karolos Papoulias, visited Albania in December 1984 - the first visit by a Greek Minister since World War II - he was asked at a press conference on his return how it was that his favourable account of the country contrasted so markedly with the picture drawn by Amnesty International. He replied:

"Amnesty International has to rely on the accounts of émigrés, which are not always accurate".

Indeed, we may judge the accuracy of Amnesty Inter national's sources of information of Albania merely by looking at the first two pages of its 1984 report. Anyone with an elementary knowledge of the country would know that Albania was not - as is said - annexed by Italy during World War II, that Albania did not break off relations with the Soviet Union in 1961, that Albania did not sever economic links with China in 1978; that political links with China have not been severed.

Amnesty International has, of course, every right to express its opinions about the facts of Albanian life - whether one agrees with those opinions or not. What is, in my view, impermissible for a responsible organ isation is to present secret - and mostly anonymous - allegations from politically hostile sources as though they were irrefutable fact. This lowers Amnesty Inter national to the level of The Sun. Not merely the Albanian authorities, but most Albanians, regard, in particular, the allegations of torture as deeply insulting.

It may be a matter of regret to the leadership of Amnesty International that the Albanians tried and shot their war criminals instead of electing them President, But I can assure this meeting that, in deciding to deprive themselves of such ''Western" amenities as a hereditary monarch and a House of Lords; of bishops, pimps, stockbrokers and porn-shops; of benevolent employers like Rupert Murdoch and films like Rambo; of nuclear weapons and foreign bases; of inflation, unemployment and taxes… the overwhelming majority of the Albanian people are convinced that they are not thereby depriving themselves of human rights but, on the contrary, are raising human rights to the most advanced level in the world today.