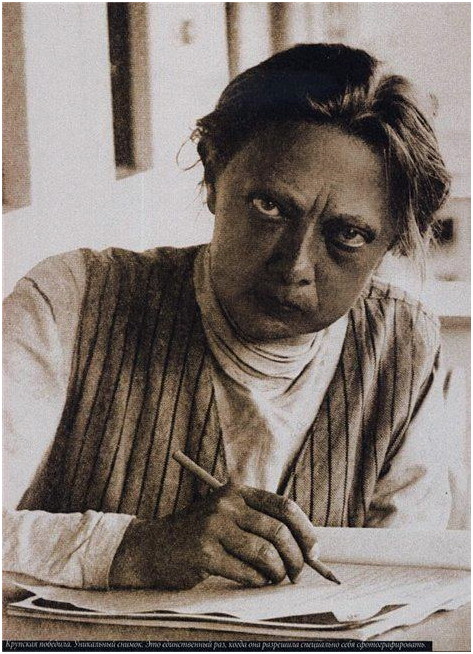

Nadezhda Krupskaya 1921

First Published: Red Virgin Soil, 1921, No 1, pp. 140-145;

Translated: Mark Alexandrovich, introduction by Renato Flores;

Source: https://cosmonaut.blog/tag/translation/.

Nadezhda Krupskaya is unfairly remembered by the identity of her husband. A glance at her page in Marxists.org predominantly shows texts related to Lenin’s persona. One of her most detailed biographies is titled “Bride of the Revolution.” But as many women of the time who have been written out of history, she was a revolutionary in her own right, standing alongside Alexandra Kollontai or Inessa Armand. She was the chief Bolshevik cryptographer and served as secretary of Iskra for many years. She was hailed by Trotsky as being “in the center of all the organization work.” After the revolution, she contributed decisively to the revamping and democratization of the Soviet library system, always pushing for more campaigns that would increase literacy and general education.

Her persistent interest in education and organization was a result of her life story. Krupskaya was the daughter of a downwardly mobile noble family: her father was a radical army officer, who combated prosecution of Polish Jews and ended up ejected from the government service, and her mother Elizaveta came from a landless noble family. Nadezhda was provided a decent, albeit unsteady education. She was committed to radical politics early on in her life, starting off as a Tolstoyan. Tolstoyism emphasized “going to the people,” so Krupskaya became a teacher to educate Russian peasants and seasonally spend time working in the fields. However, she found it hard to penetrate the peasant mistrust for outsiders and realized this was a political dead end.

Krupskaya became a Marxist when enmeshed in the radical circles of St. Petersburg. Marxism appealed to her because it provided a methodology for revolution, with its science substituting the failures of Tolstoyan mystique. After her “conversion,” Krupskaya worked as an instructor in the industrial suburbs of St. Petersburg between 1891 and 1896. The “Evening-Sunday school” was financed by a factory owner, and provided evening classes for his workers. Although she nominally taught just reading, writing and basic arithmetic, she would also teach additional illegal classes on leftist topics and helped grow the revolutionary movement. Her first-hand experience in the factories of St. Petersburg would inform her life-long interests, heavily influencing her views on the organization of production.

In this piece, Krupskaya looks at Frederick Taylor’s principles of scientific management and shows how they could be applied to the Soviet government. The early “collegiality"-based Soviet State was leading to inefficiencies all around, which produced a stagnant and unresponsive bureaucracy. Krupskaya believed that scientifically-driven organization would alleviate these organizational problems, and at the same time raise everyone’s consciousness of the work they were doing. She provided several prescriptions for the organization of production to achieve these goals, as well as a rationale for them.

Taylorism is a dirty word in leftism today. But as Krupskaya did, we have to understand that we should not hate technology itself. Technology is deployed by certain class interests. Krupskaya mentions that workers rightly hated Taylor because the scientific organization of production had been deployed to the advantage of the capitalists. But Krupskaya also believed that Taylorism could be a weapon wielded by the Soviet State so that it could be more responsive to workers’ needs. Taylorism could even be used by the workers themselves to increase productivity and work shorter hours.

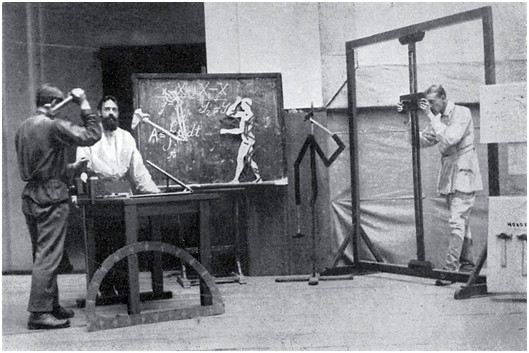

Krupskaya was not alone in her support of a Soviet Taylorism. Gastev’s Central Institute of Labor wanted the full application of Taylor’s principles to production as the best way to organize the scarce resources available. Others opposed Taylorism, understanding that it came with insurmountable ideological baggage and would alienate workers from production. This old debate sees new spins played out today in the context of automation. And while there is no longer a Soviet state to organize scientifically, we can still use the principles of Taylorism in our political organizing as Amelia Davenport recently discussed in “Organizing for Power.”

The strange thing is that every communist knows that bureaucracy is an extremely negative thing, that it is ruining every living endeavor, that it is distorting all the measures, all the decrees, all the orders, but when the communist starts working in some commissariat or other Soviet institution, he will not have time to look back, as he will see himself half mired in such a hated bureaucratic swamp.

What’s the matter? Who is to blame here – evil saboteurs, old officials who broke into our commissariats, Soviet ladies?

No, the root of bureaucracy lies not in the evil will of one or another person, but in the absence of the ability to systematically and rationally organize the work.

Management is not an easy thing to do. It is a whole science. In order to properly organize the work of an institution, you need to know in detail the work itself, you need to know people, you need to have more perseverance, etc., etc.

We, Russians, have so far been little tempted in this science of management, but without studying it, without learning to manage, we will not move not only to communism, but even to socialism.

We can learn a lot from Taylor, and although he speaks mainly about the way the work is done at the plant, many of the organizational principles he preaches can, and should, be applied to Soviet work.

Here’s what Taylor himself writes about the application of the well-known organizational principles:

“There is no work that cannot be researched to the benefit of the study, to find out the units of time, to divide it into elements... It is also possible to study well, for example, the time of clerical work and to assign a daily lesson to it, despite the fact that at first it seems to be very diverse in nature” (F. Taylor, “Industrial Administration and Technology Organization,” pp. 148).

Already from this quote it is clear that one of the basic principles of F. Taylor considers the decomposition of the work into its elements and the division of labour based on this.

Let’s take the work of people’s commissariats. Undoubtedly, there is a well-known division of labor in them. There is a people’s commissariat, there is a board of commissariats, there are departments, departments are divided into subdivisions, there are secretaries, clerks, typists, reporters, etc. But this, after all, is the coarsest division. Very often there is no borderline between the cases under the jurisdiction of the commissioner, board, department. This is usually determined by somehow eyeballing. The functions of different subdivisions are not always precisely defined and delineated. There are also states. But in most cases, these “states” are very approximate. There is no precise definition of the functions of individual employees at all. Hence, the multiplicity of institutions follows. There are, say, 10 people in an institution, and their functions are not exactly distributed. Eight of them are misinterpreted, the other two are overwhelmed with work over and above measure. The work is moving badly. It seems to the head of the institution that there are not enough people, he takes another ten, but the work is going badly. Why? Because the work is not distributed properly, the employees do not know what to do and how to do it. The swelling of commissariats is a constantly observed fact. But does it work better?

The question of “collegiality and identity,” a question that has grown precisely because of the lack of division of labour, the lack of separation between the functions of the commissioner and the functions of the collegium, the lack of separation between the responsibilities of the collegium and those of the commissioner. A misunderstanding of this seemingly simple thing often leads to administrative fiction. Thus, during the period of discussion in the Council of People’s Commissars of the question of collegiality and identity, one absolutely monstrous project was presented in the Council of People’s Commissars. It proposed to destroy not only the board, but also the heads of departments and subdivisions, it was proposed to leave only the commissioner and technical officers, to whom the people’s commissar had to give direct tasks. This project revealed a complete lack of understanding of the need for a detailed and strict division of labour. The authors wanted to simplify the office, but overlooked one small detail: if there was only a commissioner and technical staff, the commissioner would have to give several thousand tasks to the staff every day. No commissioner can do that.

The division of labour in the factory is very thorough and far-reaching. There, no one will ever doubt the usefulness of such a division.

The division of labour in Soviet institutions is the most crude, and there is no detailed division of functions. It must be created. The responsibilities of each employee should be defined in the most precise way – from the commissioner to the last messenger.

The terms of reference of each employee must be formulated in writing. These responsibilities can be very complex and extensive, but the more important it is to formulate them as precisely as possible. Of course, this applies even more to all sorts of boards, presidiums, etc.

Then F. Taylor insists on an exact instruction, also in writing, indicating in detail how to perform a particular job.

Taylor means the factory enterprise, but this requirement applies to all commissariat work.

“Instructional cards can be used very widely and variedly. They play the same role in the art of management as in the technique of drawing and, like the latter, must change in size and shape to reflect the amount and variety of information it should provide. In some cases, the instruction may include a note written in pencil on a piece of paper that is sent directly to the worker in need of instructions; in other cases, it will contain many pages of typewriter text that have been properly corrected and stitched together and will be issued on the basis of control marks or other established procedures so that it can be used” (Ibid., p. 152).

Just think how much better the introduction of written instructions would be to set up a case in commissariats, how much would it reduce unnecessary conversations, how much accuracy would it bring to it, what would it be a reduction in unproductive waste of time.

Taylor insists on written instructions, reports, etc.

The written report is much more precise and, most importantly, it is recorded. The written form also facilitates control.

Separation of functions, introduction of a written instruction allow assigning less qualified people to one or another job. Taylor says that you can’t “take advantage of the work of a qualified worker where you can put a cheaper and less specialized person. No one would ever think about carrying a load on a trotter and put a draft horse where a small pony is enough. All the more so, a good craftsman should not be allowed to do the work that a laborer is good enough for” (Ibid., p. 30).

“To put the right man on the right place,” as the English say, is the task of the administrator. Most commissariats have so-called accounting and distribution departments. These departments should have highly qualified employees who know in detail the work of their commissariat, its needs, who are able to correctly evaluate people, find out their experience, knowledge and so on. This is one of the most important jobs, on which the success of the entire institution depends. Is this understood enough by the commissariats? No. This is occupied by random people.

“No people,” you have to hear it all the time. That’s what bad administrators say. A skilled administrator can also use people with secondary qualifications if he or she is able to instruct them properly and distribute the work among them. There is no doubt,” Taylor writes, “that the average person works best when he or she or someone else is assigning him or her a certain lesson, and that the job must be done by him or her at a certain time. The lower the person’s mental and physical abilities, the shorter the lesson to be assigned” (Ibid., p. 60).

And Taylor gives instructions on how the work should be distributed:

“Every worker, good and mediocre, must learn a certain lesson every day. In no case should it be inaccurate or uncertain. The lesson should be carefully and clearly described and should not be easy...

“Each worker should have a full day’s lesson...

“In order to be able to schedule a lesson for the next day and determine how far the entire plant has moved in one day, workers must submit written information to the accounting department every day, with an exact indication of the work performed” (Ibid., p. 57).

A system of bonus pay is only possible with detailed work distribution and accounting.

In commissariats, the premium system is usually used completely incorrectly. Bonuses are not given for extra hours of work or for more work given out, but are given in the form of an additional salary. One thing that indicates this is that there is no proper distribution of business work in Soviet institutions.

Of course, only those who know the job very well, to the smallest detail, can distribute it correctly.

“The art of management is defined by us as the thorough knowledge of the work you want to give to workers and the ability to do it in the best and most economical way” (Ibid.)

It would seem that this is a matter of course, yet it is almost constantly ignored. Comrades are good administrators and, in general, good workers are constantly moving from one area of work to another: today he works in the Ministry of Agriculture and Food, tomorrow in the theater department, the day after tomorrow in supply, then in Supreme Soviet of the National Economy or elsewhere. Before he has time to study a new field of work, he is transferred to a new field of work. It is clear that he cannot do what he could have done if he had worked in the same field for longer.

It is not enough to know people, to have general organizational skills – you need to know this area of work perfectly, only then you can distribute it correctly, instruct correctly, do accounting and supervise it.

Taylor’s control is particularly important. He suggests daily and even twice a day to quality control the work of workers, he insists on the most detailed written reporting, suggests not to be afraid of increasing the number of administrative personnel able to control the work. According to Taylor, the best thing would be if it were possible to organize a purely mechanical quality control (not for nothing, the control clocks are linked to the name of Taylor).

It’s vain to write laws if you don’t obey them. And Taylor understands that all the orders hang in the air, if they are not accompanied by a strictly carried out control.

Meanwhile, in terms of control in commissariats the situation is often very unfavorable.

The purpose of Taylor’s system is to increase the intensity of the worker’s work, to make his work more productive. Its goal is to change the slow pace of work to a faster pace and teach the worker to work without unnecessary breaks, cautiously and cherish every minute.

Of course, Taylor is the enemy of all the time-consuming conversations. He tries to replace oral reports with written ones. Where they are unavoidable, he tries to make them as concise as possible.

“The management system increasingly includes a principle that can be called the “principle of exceptions.” However, like many other elements of the art of governance, it is applied on an ad hoc basis and, for the most part, is not recognized as a principle to be disseminated everywhere. The usual, albeit sad, look is represented by the administrator of a large business, sitting at his desk in good faith in the midst of a sea of letters and reports, on each of which he considers it his duty to sign and initial. He thinks that, having passed through his hands this mass of details, he is quite aware of the whole case. The principle of exceptions represents the exact opposite of this. With him, the manager receives only brief, concise and necessarily comparative information, however, covering all the issues related to management. Even this summary, before it reaches the director, must be carefully reviewed by one of his assistants and must contain the latest data, both good and bad, in comparison with past average figures or with established norms; thus, this information in a few minutes gives him a complete picture of the course of affairs and leaves him free time to reflect on the more general issues of the management system and to study the qualities and suitability of the more responsible, subordinate and employees.” (Ibid., p. 105).

What business-like character would the work of commissariats take if the comrades working there would keep to the “principle of exceptions"?

Let’s sum it up. F. Taylor believes that it is necessary:

“This is what everyone knows,” the reader will say.

But the point is not only to know, but to be able to apply. That’s the whole point.

“No system should be conducted ineptly,” notes Taylor.

Where do you learn to manage? “Unfortunately, there are no management schools, not even a single enterprise to inspect most of the management details that represent the best of their kind” (Ibid., p. 164).

That’s what Taylor says about industry in advanced countries.

Clearly, in Russia, we will not find any samples of the industry, not just of the industry, but of the administrative apparatuses. We need to lay new groundwork here. Through thoughtful attitude to business, taking into account all working conditions, it is necessary to systematically improve the health of Soviet institutions, to expel the shadow of bureaucracy from them. Bureaucracy is not in reporting, not in writing papers, not in distributing functions, in the office – bureaucracy is a negligent attitude to business, confusion and stupidity, inability to work, inability to check the work. You have to learn how to manage, you have to learn how to work. Of course, everything is not done in one go. “It takes time, a lot of time for a fundamental change of control... The change of management is connected with the change of notions, views and customs of many people, ingrained beliefs and prejudices. The latter can only be changed slowly and mainly through a series of subject lessons, each of which takes time, and through constant criticism and discussion. In deciding to apply this type of governance, the necessary steps for this introduction should be taken one by one as soon as possible. You need to be prepared to lose some of your valuable people who will not be able to adapt to the changes, as well as the angry protests of many old, reliable employees who will see nothing but nonsense and ruin in the innovations ahead. It is very important that, apart from the directors of the company, all those involved in management are given a broad and understandable explanation of the main goals that are being achieved and the means that will be applied.

Taylor, as an experienced administrator, understands that the success of the case depends not so much on the individual, but on the sincerity of the entire team.

Only this Taylor’s team limits itself to administrative employees. This is quite understandable. In general, Taylor’s system has not only positive aspects – increasing labor productivity through its scientific formulation, but also negative aspects: increasing labor intensity, and the wage system is built by Taylor so that this increase in intensity benefits not the worker, but the entrepreneur.

The workers understood that Taylor’s system was an excellent sweat squeezing system and fought against it. Since all the production was in the hands of capitalists, the workers were not interested in increasing labor productivity, not interested in the rise of industry. Now, under Soviet rule, when the exploitation of the labor force has been destroyed and when workers are interested to the extreme in the rise of the industry – a team that should consciously relate to the introduction of improving working methods – there should be a team of all the workers of the plant or factory. The capitalist could not rely on the collective of the workers he was exploiting, he relied on the collective of administrative employees who helped him to carry out this exploitation. Now the working collective itself has to apply the most appropriate methods of work. He only needs to be familiarized in theory and practice with these methods. This is production propaganda.

As far as the employees of Soviet institutions and people’s commissariats are concerned, it is necessary to familiarize them with the methods of labor productivity. This falls on the production cell of the collective of employees. But only by raising the level of consciousness of all employees, only by involving them in the work of increasing the productivity of commissariats – it is possible to actually improve the state of affairs and destroy not in words, but in practice, the dead bureaucracy.