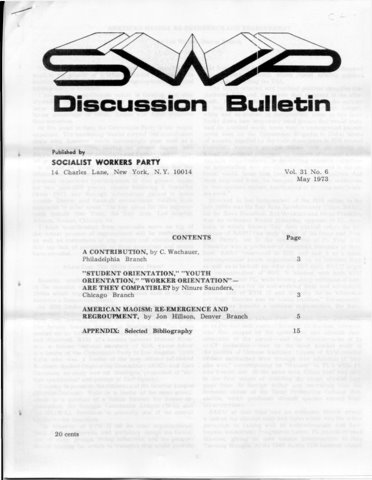

First Published: SWP Discussion Bulletin, Vol. 31, No. 6, May 1973.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The purpose of this contribution is to describe and analyze the growth of a layer of Maoist radicals in this country who are in the process of regroupment.

I believe this pro-Chinese milieu is forming and may crystallize into a national party formation of a size as large as, if not larger than the SWP, possibly with a larger percentage of Black, Latino and Asian members than ourselves.

At this point in time, the Communist Party is our major opponent. The hardening Maoist current this contribution deals with, however, could increasingly pose itself as a serious opponent force, having far greater impact than the various Trotskyist sectarians and flash-in-the-pan ultra-left groupings.

It should be stated at the outset of this piece that my information and perspectives on this layer are based on personal experience (participation in that general milieu for two post-SDS years), closely following it thereafter (from 1971 on) through information gained in areas outside Denver and through second-hand insights from comrades in other areas. The key areas for this regroupment include New York, the Bay Area, Los Angeles, Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, etc.

I hope amplification from comrades more on top of the actual process of regroupment will be forthcoming, as well as corrections of any errors and misinformation that my lack of proximity to these groupings and events have revealed.

Broadly speaking, its core appears to be a product of the remains of the large-scale ultra-leftism of the late 1960s which organizationally expressed itself in the Students for a Democratic Society.

As SDS broke up in 1969, the Revolutionary Youth Movement faction which expelled the Progressive Labor Party split into two warring groups, RYM I and RYM II. The former became known as Weatherman. The latter carried on an independent, dwindling existence for a year and dissolved. RYM II’s leaders included Michael Klonsky, a former national secretary of SDS, whose father is a leader of the Communist Party in Los Angeles; Lynn Wells who was a leader of the now defunct left-liberal Southern Student Organizing Committee (SSOC); and Carl Davidson, an early new left ideologue, proponent of “student syndicalism” and protégé of Carl Oglesby.

Klonsky is presently the chairman of the October League (Marxist-Leninist). Wells is a leader of the same group, (which is a product of a fusion between her former organization, the Georgia Communist League (M-L) and the OL(M-L). Davidson is presently one of the central figures on the Guardian.

The breakup of RYM II left no clear organizational focus for its adherents and periphery except the formation of study groups, living collectives, and the perspective of waiting for events to transpire that could provide that focus. Many people in the general SDS milieu dropped out of politics entirely; others joined existing political tendencies, including the YSA.

The clique-oriented and jumbled political struggles that shattered SDS and the events that occurred in the aftermath, however, did not succeed in forcing the entirety of that layer altogether from political activity. Largely white and ex-student in composition, some in this layer broke down into temporary local groups that would study and do political work; some went to underground papers; some went on the Venceremos Brigades to Cuba; layers of women, repelled by the male chauvinism in SDS formed (ultra-left) women’s groups; others took on activity in behalf of political prisoners, in support of colonial armed struggle organizations, in developing research collectives on imperialism and revolutionary movements in the colonial world. Some took longer leaves from politics. And most migrated from the campus bases of their radicalism to metropolitan centers, anticipating or moving into “workers work.”

Involved in but independent of the SDS milieu in the late 1960s was the Bay Area Revolutionary Union. BARU, led by Steve Hamilton, Bob Avakian and Bruce Franklin, was an orthodox Maoist grouping, opposed to PL. Avakian, a widely known Bay Area ultra-left before the formation of BARU (an early leader of the Peace and Freedom Party), led in the reading out of PL from SDS. Franklin was a professor of American literature at Stanford. BARU intervened in SDS and saw it as a mass, anti-imperialist youth organization, to be recruited from as well as to be built up. After the SDS split, BARU urged the reconstruction of SDS. It blocked with both RYM factions against PL, while having sharp criticisms of both of Weatherman for its anti-working class and adventurist politics and of RYM II and Klonsky for its “white-skin privilege” theories and its “social pacifism.” Subsequently, BARU has become a national organization, the Revolutionary Union.

The Progressive labor Party claimed, in the late 1960s, to be the authentic voice of Maoism. Its Maoism, however, was also shaped by the spontaneist and ultra-left characteristics of the period – and the idiosyncrasies of its ex-CP leadership–than by the most detailed study of the politics of Chinese Stalinism. Layers of RYM-oriented SDSers embraced Mao through their adulation of “people’s war,” counterposing its “Maoism” to PL’s while PL was booted out. At the same time, China itself was only in the first stages of shedding the excess ultra-left baggage from its foreign policy and recovering from the domestic chaos of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, which produced ultra-left spasms among Maoists everywhere.

BARU at that time was an orthodox Maoist group; it lacked the ultra-left snap and verve which was the major attraction to (along with its antinationalism and flamboyant workerism) Progressive Labor. PL passed through Maoism, giving its own unique interpretation to Mao Tse-tung thought. At the 1969 Austin SDS national council meeting; one could hear Bob Avakian give an eloquent polemic in defense of Black nationalism and the right to self-determination against PL’s antinationalist economism; one could hear SDS “peoples-war” Maoists castigate PL for its opposition to the NLF and the character of the Vietnamese revolution. It could be that the hesitation of coming to Maoism–no matter the variants in which it has appeared–by SDS leaders was a result of their initial belief that PL represented Maoism.

Around the time of the Chinese betrayals of Bangladesh and the young insurgents of Sri Lanka, PL completed its formal rejection of Maoism, though it considered the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution to be, along with the Paris Commune, the singular examples of workers revolution in modern history. PL argued that a revisionist Soviet-type bureaucracy had taken power in China under Mao’s leadership and fundamentally restored capitalism. It also affirmed a vulgarization of the theory of permanent revolution against the two-stage theory as its own.

In this process, PL lost its Chinese “franchise,” its major aspect of attraction. PL’s experience in SDS, the collapse, internal struggles, frenzied attacks on opponent groups and resultant demoralization, and its declining influence have reduced the organization to a cynical, diehard cadre in the shell of a bureaucratically run sect. It is a sect which, having sought to carve a path independent of Stalinism and Trotskyism, has become nothing more than what it could and had to eventually become: an opportunist, reformist organization in the tradition of Social Democracy.

The Maoist current now germinating is one which existed at the time of and in opposition to PL in its position of Maoist hegemony. The collapse of PL was not the collapse of Maoism, but the disintegration of a party which considered itself, for a time, Maoist. The death certificate of Maoism was prematurely signed by those who believed PL represented what Maoism was.

In the past four years since the SDS breakup, the radicalization has continued to forge new partisans of socialist revolution. It isn’t necessary to go over the intense events which have shaped a deepening antipathy in mood and action among large layers of the population, especially young people, to American capitalism. In those interceding four years, however, ultra-left actions, schemes and gimmicks – in opposition to the healthiest dynamics of the radicalization, and to the key leadership organizations which have sought to organize those dynamics in action – have tempered new layers which have been increasingly drawn to the Maoist pole. That is, people involved in May Day, in “new” collective experiments, in anti-imperialist contingents, ultra-left women’s groups, etc., have added to the size of the Maoist milieu. This process has occurred over a period of time when the most raw forms of infantilism in the left have been sifted out, where spontaneist ultra-leftism, confrontationism, counter-institutionalism (the struggle for “revolutionary” lifestyles), anarchism, etc., no longer have the sway and prominence they once had.

Workerism, as both a conservative, mechanical response to the character of the student stage of the radicalization and as an economist and unrefined rejection of “youth as a class” notions and acceptance of the strategic, world historic importance of the proletariat as the revolutionary class has become the focus of this layer, replacing “third worldism,” civil disobedience, “new working class” and “the working class is bought off” petty-bourgeois ideologies.

This has coincided with increasing acceptance in this layer of the spoken need for a revolutionary party, disciplined and of national scope. This is a reflection of their consciousness of the failure of spontaneist and confrontationist notions of action, and represents an understanding of the toughness of the struggle for socialism and the tools that struggle requires.

Their understanding of the need for a revolutionary party comes also – and this is of elementary importance – as a response to the growth, prestige and impact of the SWP and the YSA. And, of course, the platitudes of Maoism indeed call for the formation of revolutionary combat parties.

This milieu is welded by its deep bitterness and enmity for our movement: the pressure exerted by our ideas in mass movements has impelled these forces towards organizational cohesion. Their quest for an “alternative” to revolutionary Marxism and principled politics, given their own increased, however vulgar, awareness of the serious business of making a revolution, could only lead to a variant of Stalinism. Anarchism had shown its incompetence and futility; SDS could not repeat itself in the politically anemic “New” American Movement; the Stalinism of the Soviet Union and the politics of its diplomatic front, the Communist Party, held for very, very few any possibility whatsoever.

Maoism and the Chinese bureaucracy have become, at once, the magnet for this anti-Trotskyist layer while at the same time the Stalinist ideology of Peking brings into an organized and internally logical focus the inchoate politics of this layer that could lead it to the formation of a party. Any milieu can dissipate without a focus. Given the increased ante as the American class struggle heats up, and as international struggles continue generally unabated, the mood, the gel of anti-Trotskyism alone is too weak to withstand pressure for any great period, especially if the mood nods toward party-type organization.

That party cannot be formed, that milieu could not, cannot crystallize, that mood would have dissipated into private frustration and frenzy, without the conscious adhesion of critical layers to Stalinism; to its world view, strategic and programmatic perspectives, to the most “complete” “left” critique of revolutionary Marxism.

With the unhealed cleavage of the Sino-Soviet split deepening, with China beginning to rival the Soviet Union for the privileges granted to its bureaucracy by imperialism for class collaboration, with a detente between the U. S. and China engineered by the American ruling class (and a consequent bourgeois propaganda campaign to warm the American people to China), the emergence of this Maoist layer comes as no coincidence.

The Guardian, a key mouthpiece of this layer, describes this period as characterized by the “emergence of Peoples’ China as a recognized world power.” The course chosen is one of class collaboration, international popular frontism, diplomatic deals and collusion with imperialism– all in all, the process of cementing a turn in how to take on the Soviet Union. The Peking bureaucracy now dubs Russia the state which is the source of “the primary contradiction.” To sidle most closely with imperialism, Peking takes on Moscow; 10 years ago, Peking challenged Moscow through an ultra-left foreign policy of support to colonial guerrilla movements. A decade of maturation has indicated the best source of “influence” lies in dickering deals with the governments those guerrillas seek to topple.

The Maoist milieu hardens at the time of detente, of a prolonged and deepening right turn.

The Guardian calls this a victory. The “victory” of Peking’s collusion with imperialism prepared, secured and is part of the Vietnamese “victory” codified in the Kissinger-Le Due Tho accords. It was these accords, and their antecedents in the seven- and nine-point PRG proposals which drew this milieu’s “mood” into focus in the antiwar movement.

That concrete activity last fall around the accords forged an increased self-consciousness and unity in this layer, inspired it, and deepened, in some quarters, its optimism for regroupment.

We should note the size and success of the Maoist antiwar intervention. It was mobilized nationally through the Guardian. Built up in New York City around the November 4 Coalition (so named for the date of its action) around the slogans of stop American aggression, defense against attacks on the American working people, and stop racist and national oppression, the action took on a “sign-now” character and drew 3-4,000. NPAC’s action two weeks later drew under one thousand. On January 20, the RU-inspired Inauguration Day Coalition (which in principle excluded the CP and the SWP) had no bourgeois press, drew 3,000 in San Francisco. NPAC and PCPJ’s united action drew 5-10,000 on the same day. Those actions, and other smaller local ones, represented the coordinated attempt by this Maoist milieu in the antiwar movement. The November 4 Coalition was animated by the Black Workers Congress, the Puerto Rican Socialist Party, I Wor Kuen, RU, and the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization, among others. In the Bay Area, RU was central in the IDC, involving other Maoist groupings, the Black Workers Congress, I Wor Kuen, etc.

These actions, their organizing meetings, their propaganda (counterposing “sign now” to “out now”) add, no doubt, another new layer to the Maoist milieu. In fact, in a number of areas where the CP and YWLL are small or nonexistent – and where this milieu does exist – the preponderance of “sign-now” propaganda was their project.

Between the organized, major tendencies and the unorganized, sympathizing periphery, there exists another category being drawn to the tendencies. These are people organized into study groups and collectives, which publish some 20-30 monthly “workers papers” in as many large American cities. These papers, whose proliferation is on the upswing, tend to be ultra-left and economist, though not stridently ideological. They feature local union struggles, interviews with rank-and-file workers on bread-and-butter issues, articles about the war, equal-pay struggles, workerist analyses of Black and Chicano struggles, etc. These papers reprint articles from each other, the Guardian, and the papers of RU and the OL (M-L). Their circulation varies from several hundred to several thousand a month. Some have small sections in Spanish. These papers, collectives, study groups – many of which have implanted themselves in industry – tend to be a bridge between the organized groupings (the larger ones) and the general Maoist mood, the periphery. The October League, for instance, recently fused with three such collectives (with names like the “Red Star League”) to build branches in New York, Chicago and Baltimore-Washington.

* * *

The picture that emerges is one of radicals, some of whom are not neophytes on the left, some of whom are serious. Their ranks are being reinvigorated by the process of regroupment itself, which has boosted the morale of disaffected and inactive anti-Trotskyists, drawing them into motion, and by the attraction to the regroupment of another layer of radicals, many newer, unable to grasp principled politics, the subtle and tricky shifts of the radicalization, the very meaning of radicalization itself and the strategy and analysis it demands, and who have had little or no exposure to Trotskyist politics.

This milieu, from the organized tendencies to the semi-organized layers to the base, is distinct and sharply demarcated from the layers of the radicalization from which we have tended to recruit the most from: the broad, large, healthy layers of radicalized youth on the college and high school campuses and young working people from the mass movements.

While, because of the detente, there will no doubt be enhanced popularity of “Peoples” China, and hence, enlarged recruitment possibilities for a time, the new Maoists’ arena for recruitment is narrowed because of its general politics: obeisance to Stalin, antifeminism, anti-nationalism, antigay politics, its sterile workerism (though its workerism is attractive to certain layers as well), its bureaucratism, and, last but not least, its latching on to the coattails of a right-turning counterrevolutionary bureaucracy. These perspectives, no matter how muted or submerged, will not generally entice the far broader, eminently more healthy layers drawn to the programs of the SWP and the YSA.

The Guardian has been undergoing a process of developing political homogeneity and cohesion – insofar as that is possible for it – since the SDS breakup when it called for a “new, new left.”

It is more consciously pro-Chinese, pro-bureaucracy than ever before. While for approximately two years it has been calling for a new “Marxist-Leninist party based in the working class,” the Maoist clarion has been within the last year. As recently as one year ago, the Guardian, as if sticking a toe in the icy and unknown waters of the Stalin-Trotsky debates, in its Voices of Revolution column printed Trotsky on fascism one week and Stalin on the national question the next. Such deviations are not tolerated now. The vague Maoism of a year ago has been pared to its rational, irreconcilable core: Stalinism.

Internally, the Guardian was divided on what its staff jokingly called the “60-40” question. That is, is Stalin criticized 60 percent or 40 percent? From the recent Davidson polemical series on Trotsky and Trotskyism, which is a product of the Stalin school, from Silber’s essentially unqualified support of the Stalin period’s decisive role in building socialism, and the periodic references to Stalin on the two-stage theory, the national question and peaceful coexistence, the 40 percenters won out. Doubtless, the percentage is quite lower now.

The Guardian has a more consciously interventionist perspective now than since the SDS breakup. By interventionist I mean it specifically orients towards tendencies and a certain milieu for organizational and political goals; it engages in public debate on line and strategy with these groups; sends its leading spokesmen (Davidson, Jack Smith, ex-CPer Irwin Silber) on speaking tours around the country; engages in leadership discussions with RU, the OL(M-L), the Black Workers Congress, I Wor Kuen, the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization, the Puerto Rican Socialist Party, etc.; plays a political and organizational role in the November 4 Coalition; interviews the leaders of the tendencies in its press, criticizes their groups’ strategies, reprints articles from their papers and engages in joint action with them (antiwar, forums, etc.).

The Guardian at the outset of the period in which it called for simply a new revolutionary party, conceived of itself as an Iskra in concept; to be a propaganda pole, organizing sympathizers around its “program.”

The process of the Guardian’s development of political clarity is hardly complete; its editorials tend to be vague and general, avoiding the specificity of the columns by Guardian leaders Davidson and Silber, which take on the disputed and undecided questions. I want only to point out the role of the Guardian; with a steady circulation of 18-20,000, a following no doubt shorn of CP sympathizers who have been recoiling from the sharp “anti-Soviet” polemics in the paper, the Guardian is the national forum and paper of the new Maoist milieu. Lacking an organized following, its strength rests on its reputation as the largest, strongest, most widely read alternative to The Militant, its ability to reflect the general mood of the Maoist milieu which in its large majority has not yet lined up with the tendencies, or, in fact, local fairly strongly organized collectives. And, finally, the Guardian, known as the old pro-SDS paper, retains a loyal following from those remnants still active.

The Guardian forums, held in New York and organized with all the tendencies participating, have drawn large crowds. The forums have ranged over the gamut of topics, from China to the women’s movement, from the Black struggle to the strategies for building a new party, the workers movement, and the “anti-imperialist” wing in the antiwar movement. They have averaged 500, with the new party forum drawing 1300.

The Guardian, because of its role – it reprints the forum statements of the differing Maoist groups, for instance – as the key paper of regroupment, should be required reading for comrades.

The Revolutionary Union is the largest Maoist cadre organization in the country. The first issue of its monthly paper, Revolution, came out in February of this year. It publishes an irregular theoretical journal called “The Red Papers.” Since the organization was formed more than four years ago, six have come out, dealing RU’s basic program, from strategy and tactics, to the national question and the role of women in the struggle for socialism. Its most recent issue is 77 pages in length and is entitled “Proletarian Revolution and National Liberation.” RU has published a variety of pamphlets dealing with topics ranging from the 1972 Temple University workers strike to the Wallace assassination attempt to the defense of Chinese foreign policy, to the group’s strategy for the student movement. Approximately seven have printed. The RU paper and the most recently printed pamphlets have sections translated into Spanish.

RU has 14 mailing addresses in 11 cities on the east and west coasts and in the midwest. It has members in perhaps 5-10 other cities not listed on the mailing list. Its members are involved in monthly “workers” papers in at least Trenton, Cincinnati, Denver, San Francisco, Cleveland and Detroit.

In the fall of 1970, a struggle erupted in RU between factions headed by Avakian and Bruce Franklin. At dispute was a strategy which saw urban guerrilla warfare counterposed by Franklin to the RU majority’s conception of party building through deliberate work in factories, communities, schools, etc. Franklin’s group called for RU to seek military leadership in spontaneous Chicano and Black rebellions and to prepare for armed struggle. Avakian led the polemic against Franklin’s “bourgeois adventurism” which anticipated the Franklin group’s expulsion. The expulsion led to the formation of the Venceremos group, which is apparently in the process of being shattered by police infiltration and consequent victimization. The entire discussion took place in the central committee of RU. The ranks were not allowed participate in the discussion.

RU is a semi-clandestine organization, recruiting over a long period on a selective basis. It calls for revolutionaries to be methodically prepared for illegal and armed struggle.

RU appears to have a good-sized layer of Black, Latino, and Filipino cadre. Because of its semisecret form of organization, however, it is hard to ascertain much more than an educated guess.

RU does not see itself as the “new party.” It seeks the formation of a new “Communist Party, based on Marxism-Leninism-Mao-Tse-tung thought” emerging from a process of political collaboration on joint work, debate, discussion of respective programs between groups collectives, whose activity and ideas will forge the program of that party.

RU is a bureaucratic-centralist organization. Its conceptions of democratic centralism are applied from those articulated by Mao Tse-tung in ”Role of the Chinese Communist Party in the National War.” They are:

1) The individual is subordinate to the organization;

2) The minority is subordinate to the majority;

3) The lower level is subordinate to the higher level;

4) The entire membership is subordinate to the central committee.

RU considers points 3 and 4 aspects of “top-down” leadership, which “embodies the principles in a communist organization to equip us for our fighting task and also enables a communist organization to develop a political line on the basis of a Marxist theory of knowledge, on the basis of mass line.” RU states that ”top-down” leadership differentiates communist organizations from those practicing “formal democracy.”

RU’s strategic orientation is the construction of a “united front against imperialism” headed by the proletariat and under the leadership of the new Communist Party. According to RU, there are five “spearheads” in this front. They are:

1) The liberation struggle of the oppressed minority nationalities;

2) The fight against imperialist wars of aggression like Vietnam;

3) The defense of democratic rights and opposition to the growth of fascist repression by the imperialist state;

4) The battle against the oppression of women;

5) Resistance to the monopoly capitalists’ attack on the people’s living standards.

This concept of the united front views it as the vehicle which coordinates and unites the various struggles of a proletariat divided by white supremacy and sex oppression against the capitalist state, smashes it through armed struggle and forms the proletarian dictatorship. The November 4 Coalition appears to be the closest approximation of the RU strategy in action.

RU considers the national question “the key question which must be solved by communists in the US.” It states that while the contradiction between bourgeoisie and proletariat is fundamental, the contradiction between “the Black Nation and imperialism” is primary.

RU considers the Black population in the United States to be concentrated into a “nation of a new type,” that is, newer and meeting different criteria than those established by Stalin (common language, territory, economic life, psychological makeup, culture). The Black nation previously existed in the Black Belt; the ”nation of a new type” exists primarily in the urban centers and was created by the proletarianization of the Black nation. RU sees the national question as a class question, the resolution of it being the proletarian revolution which will accomplish the emancipation of the colonized peoples “in one sweep.”

RU affirms in its program the right of the Black nation to secede and form an independent nation. It calls for the defense of separatist organizations (Republic of New Africa, Nation of Islam) against racist attacks. When the Panthers were a political force where RU organized, RU stepped aside in the Black community.

RU does not call for a Black party. It does not deal with the struggle for community control, although it calls for all-Black organizations in the community, as well as Black caucuses in the plants. It does not deal with the phenomena of Pan-Africanism, nor does it mention the African revolution. It has no clear strategy for nor orientation to Black students. Its support for Black nationalism liquidates the struggle for community control into Black workerism. RU believes the SWP separates the national struggle from the class struggle. It has intervened in African Liberation Day activity.

Though RU has not advanced as yet an analysis of the Chicano struggle as retailed and worked out as its perspectives on the Black struggle, we can anticipate its perspective from this statement in “Proletarian Revolution and National Liberation”:

“For the Chicanos, as for the Black people, the right of self-determination must be upheld, but the heart of the Chicano liberation struggle is the driving force it provides for the equality and revolutionary unity of the entire working class against US imperialism.”

RU is antifeminist. It sees feminism as petty-bourgeois. It reduces the struggle for female emancipation to a specific orientation to working women around equal pay, daycare, etc. It has aspects of counter-institutionalism in its outlook (build up daycare centers). Earlier in its history, RU called for free abortion on demand and no forced sterilization. It appears that RU abstained from the abortion struggle, however: it did so quite probably on the basis of: (1) repeal is not enough; (2) the “anti-family” aspects of abortion attack working-class families; (3) abortion is used against the Black and Chicano communities; (4) the relationship of forces in the abortion law repeal movement.

RU does talk about women overcoming sex-role stereotyping, but rarely if ever mentions sexual oppression. In its second Red Papers it referred to J. Edgar Hoover as J. Edgar Faggot. This attitude has not changed. RU stands publicly for heterosexual monogamy and the family.

RU opposes the Equal Rights Amendment while it calls for equal pay for equal work. It stated that the ERA was an attempt to co-opt and exploit working women and that its enactment would benefit the capitalist class. The Guardian has publicly opposed RU on this. RU built International Women’s Day actions in several cities, drawing 300 in San Francisco and crowds of upwards of 100 and 150 in several other cities. Their character was workerist and laudatory of China’s liberation of women.

RU’s international line is the line of the Peking bureaucracy. It has unconditionally defended China on Pakistan-Bangladesh, Ceylon, and Vietnam. It agrees with China’s position on the “united front against the superpowers” (all the nations against the US and USSR). It supports the two-stage theory for the underdeveloped nations. It believes that capitalism has been restored in the Soviet Union and its satellites (I do not know if that includes Romania, which has been dickering for China’s support.) It says very little about Cuba, although RU members have gone on Venceremos Brigades and recruited from these activities.

RU considers the CP, in the long run, “... the most dangerous, best organized and best funded representative of imperialism within the revolutionary movement.” The SWP is the right wing of the Trotskyist movement. PL is the left wing. RU considers the exclusion of PL, the SWP, and the CP from united fronts a principled question. RU appears not to be opposed in principle to the use of physical violence against opponents on the left, notably the Communist League, which is described below.

RU, while workerist, has always had some campus members, even though it lost nearly its entire base in the Venceremos split-off. Its analysis of and strategy for the student movement is documented in a 56-page pamphlet entitled “Build the Anti-imperialist Student Movement.” RU suggests the left-wing student movement be “re-built” (since the dissipation of SDS) around a perspective of linking up with the working class while being involved in work areas to include: the antiwar movement, defense of the prisoners’ movement, anti-imperialist struggle in general, the struggle against education cutbacks and the building of study groups.

RU is in the leadership of the Attica Brigade, which recently held a regional meeting of 250 in New York City. Its “principles of unity” are “support for national liberation struggles abroad as exemplified by the NLF and PRG and support for the struggles of the oppressed at home.” The Attica Brigade has worked with the Puerto Rican Student Union, helped to build the anti-imperialist contingent in the January 20 Washington demonstration and is a pole for some ultra-left students in New York City. Apparently, through the initiative of RU, it is branching out. It explicitly excludes the CP, the SWP and PL.

It appears to be taking an interventionist perspective to campus struggles, “workers’ issues,” the prisoners’ movement, etc. It calls for “all-Third World” anti-imperialist student organizations. RU considers the Attica Brigade the initial step in rebuilding the “anti-imperialist student movement.” RU, like the Guardian, considers students essentially petty-bourgeois. It has called for an autonomous “Third World” anti-imperialist student organization.

RU holds Stalin in the same esteem as the Chinese leadership. Minor admonitions are made for his “commandism,” and other “secondary flaws,” but the man Stalin and the policies with which his name is synonymous retain a high accord in RU. Stalin’s politics are “the organizational, theoretical and political bridge” between Lenin and Mao Tse-tung.

The reemergence of American Maoism means the revival of the debates between Trotskyism and Stalinism, the Stalinism of the Stalin era itself, in the context of the Mao Tse-tung dictatorship. While the CP does not publicly embrace Stalin – and supports the “de-Stalinization”–RU and the other Maoists; name Stalin in the litany of revolutionary giants, along with Marx, Engels, Lenin and Mao Tse-tung. For RU the period of the Khrushchev revelations is the time in which the proletarian dictatorship constructed by Stalin was broken, and, in that breach, where revisionism seized the Soviet CP, to lead the Russian workers stats to capitalist restoration. RU counterposes Stalin to Khrushchev, Brezhnev, et al.

Last year, Anchor Books printed a collection entitled “The Essential Stalin,” which was edited by ex-RU leader Bruce Franklin.

While RU has a primary industrial concentration and secondary campus orientation, it has also done work with the farmworkers (not UFW, per se) in the Salinas valley and with Filipinos in California.

It has played a role–the extent of which is undetermined– in support committees, built around the Farah strike, as well as other similar formations.

RU recently moved its national headquarters from Chicago to Detroit. I would estimate its membership as large as 200.

The OL(M-L), whose history has been described earlier in this contribution, is based in Atlanta and Los Angeles. In late 1972 it sponsored a conference of “communists in industrial work” which drew over 100 people from collectives in the South and Midwest.

The politics of the OL(M-L) are publicly less well defined than RU, for several reasons. It is a newer organization, the product of two smaller groups separated is a wide geographic distance. It lacks, in this context, the resources alone to publicly promulgate its ideas.

Its national newspaper, The Call, which is a monthly of professional quality, began publishing in late 1971. The OL(M-L) has published two pamphlets, one dealing with women’s liberation, the other covering the basic unity document of the old OL(M-L) and the Georgia Communist League.

In Los Angeles, the group is strongly involved in the Chavez-Ortiz defense committee, “anti-imperialist” antiwar work, participates in the forums held by the Long March, a citywide Maoist meeting place. In Atlanta, Sherman Miller a Black member of the OL(M-L) was singled out by reactionaries and reformists alike and red-baited for the central leadership role he played in the Black caucus of the Mead Strike, on which The Militant carried a long story. Of the 40 caucus members fired because of political reasons, including Miller, approximately 32 have been rehired. The OL(M-L) has made a film of the strike and toured Miller around the country. From what our own press has said, the OL(M-L) conducted itself in a serious fashion in the strike, and, when Miller was under intense attack, approached us for support, which we gave.

The Call recently began a series entitled “the road to a new communist party,” which began with a sympathetic recounting of the work of William Z. Foster and his attempt to “rebuild” the CPUSA after the Browder period into a revolutionary vehicle. The Maoists generally revere, quote and refer to Foster as the best example of a revolutionary workers’ leader and party builder.

The OL(M-L) has perspectives on the building of that new party similar to RU’s. It, like RU, sees itself as one organization struggling to bring about this new party through joint, collaborative political work and debate; it calls for a multinational party, as does RU.

It has little discernable public differences with RU on strategy, orientation, the national question and women’s liberation, although it appears that OL(M-L) is less sectarian on the feminist movement and supported the ERA. It jointly sponsored with NOW, for instance, an International Women’s Day conference in Atlanta this If year.

It appears the Guardian is more sympathetic to the OL(M-L) than to RU. The OL(M-L) supported (not publicly) Carl Davidson’s criticism of RU’s position on the national question. (Davidson leans to self-determination in the Black Belt, support for the “democrat content” of community control demands, and stresses slogans around “equality” as opposed to “self-determination.”) While the Guardian has publicly criticized a number of RU stands (on the national question, their opposition to ERA and to busing) it has subtly and formally complimented the OL(M-L)’s work, and, in some areas (the group’s initiation of “united front activity” on International Women’s Day) considered it a model.

With Maoists, generally, program and strategy are muddled, and the element of leaderships –and their personalities– play a large role. Given the probability that a Maoist party in this country would be founded with not a little opportunist give and take, and based on unprincipled politics, there is no reason to believe that the OL (M-L), RU and the Guardian could reach temporary agreement, especially if there can be enough seats on the politbureau and national titles to satisfy the emerging bureaucrats from the respective groups, cliques and stars.

The OL(M-L) is adamant about Stalin’s positive and major contributions to the class struggle. Like RU, it refers to Stalin’s writings in articles in its press. It supports the Stalinist-Menshevik two-stage theory of revolution in the colonial countries, adhering to its Maoist variant of the “new-democratic revolution.” Like RU, it sharply polemicizes against the CP’s “anti-monopoly coalition” strategy and the Moscow Stalinists hope for a peaceful transition to socialism.

RU, the OL(M-L) and the Guardian see the “main danger” to building the new party as “ultra-leftism.” The meaning of this is oblique, but it appears to dovetail the most recent intra-bureaucratic struggles inside the Chinese Communist Party between Lin Piao’s “ultra-leftism (a carry over from the days of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution).” That fight appears to have reflected itself internationally in Lin’s alleged opposition to the Chinese detente with imperialism, and Mao’s domestic “mass line” of reintroduction of the “renegades” of the Cultural Revolution into leadership, and the increased detente with the US and stepped-up polemics with the Soviet Union (which made the “social imperialism” of the Soviet Union more dastardly an enemy than American imperialism, a theory that Lin opposed).

What the warnings of “ultra-leftism” appear to mean, as enunciated by these tendencies, is to harden around, to more closely follow, to be most submissive to the diplomatic course of the Chinese bureaucracy. This unconditional defense of international class collaboration is indeed, for the Maoists, a far more principled question, a greater cement of unity, than disagreement on varied tactical and, to some extent, strategic concepts in the domestic arena.

The October League holds that capitalism has been restored in the Soviet Union, that “. . . new Tsars now rule the Soviet People with an iron heel of fascism . . . [which] transformed most of the people’s democracies into semi-colonial puppet states.”

The Guardian has not yet been so categorical; this, however, is most attributable to the fact that the Guardian is still in its early stages of acclimating to a hardened Maoist perspective.

As previously mentioned, the OL(M-L) has recently built new branches up, out of fusions with Maoist collectives, in Chicago, New York and Baltimore-Washington.

It may have near 100 members.

The Communist League originated from a grouping of ex-CPers in the late 1960s. It is opposed to and excluded by RU, the OL(M-L) and the Guardian from serious consideration in the formation of the new party. I include it only as a point of reference.

The CL is the most hysterically anti-Trotskyist of the new Maoist groups. It is suspect of individuals who are on anything that approximates fraternal relationships with the SWP or YSA, and has held six-month internal classes on Trotskyism, which it considers deliberately synonymous with fascism and police agentry.

The CL is semi-underground. It underwent a period where all recruitment was stopped for fear of police infiltration.

The group has an unreconstructed Black Belt theory, calling for an “independent Negro nation.” It denies the real existence of Canada, calling this continent the “United States of North America” which is divided into an “Anglo-American nation” and a “Negro nation.” It calls for “regional autonomy for the Mexican national minority.” It is antifeminist, abstains from practical work (it considers study key at this point in time), is stridently sectarian to the other Maoist groups which it considers involved in periodic blocs with “the Trotskyites” or “social imperialists” or both against themselves.

The most interesting feature of this group is that it took the bulk of the membership of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers after that organization split over nationalism. The tendency emerging against the majority’s Black Belt position was the antinationalist and workerist Black Workers Congress.

The CL publishes a paper which appears to be bimonthly, called the People’s Tribune, which has a section in Spanish.

The Communist League may have near 100 members in Southern and Northern California, Chicago, Detroit – where it is largest, but inactive (studying) – Brooklyn and Denver.

The group has called, with several tiny Maoist grouplets in Canada and the U.S. a May Day conference to build a new party of the “United States of North America.”

The CL appears to be under the threat of physical violence from RU and has been declared persona non grata by all the groups in the new Maoist milieu. The CL believes RU is in the conscious pay of the American CP; the October League is said to be pro-Trotskyist.

The PRRWO was founded about a year ago. It was previously known as the Young Lords Party. At the founding convention, RU, the BWC, the Guardian, the OL(M-L) and I Wor Kuen attended as fraternal organizations, invited by the old YLP.

The PRRWO is workerist. It has not participated in the Fuentes/District: 1 community control struggle. As a central member of the November 4 Coalition, the PRRWO participated in the calling of a New York city-wide “workers meeting,” which drew 400 predominantly Black and Latino workers. The meeting came up with no specific strategy. The group’s press deals mostly with local community problems (health care, police brutality) while some international news is printed.

One of the PRRWO’s leading spokespeople is Juan Gonzales, who has become widely known in our movement for his role around the January 20 demonstration, at which, in Washington, he attacked us by name from the podium for “scabbing on the Vietnamese.” Gonzales was a leader of the 1968 Columbia strike as a member of SDS. Soon after the strike he left SDS, playing no central role in its collapse and became a leader of the YLP. He was a major spokesperson when that group occupied a barrio church and made it a community center, dispensing food and health care. He is currently up on a draft evasion charge.

The PRRWO played a major role in building the November 4 pro-treaty demonstration as well as the anti-imperialist contingent which marched several thousand in numbers in Washington, DC, on January 20. Gonzales spoke for the contingent. The PRRWO is in solidarity with the Chinese leadership. Some of its leaders have been to China.

Concentrated in New York City, the PRRWO considers the Puerto Rican people in the continental United States a “national minority,” and not part of the Puerto Rican nation on the island, which it considers a colony of US imperialism. While it calls for an independent, socialist Puerto Rico, it sees its role as being part of a multinational Marxist-Leninist party which will lead the American workers to power, end national oppression domestically and liberate colonized Puerto Rico. It has no special orientation to Puerto Rico and does not call for self-determination for the domestic Puerto Rican community.

This appears to be one of the central disagreements between the PRRWO and the Puerto Rican Socialist Party (PSP), which is far larger and mote influential than the PRRWO in the continental US and in Puerto Rico, where it has an estimated 3-5,000 cadre.

The PSP contends that the domestic Puerto Rican community is intimately linked to and part of colonial Puerto Rico, and that the role of the American zone of the party is, while engaging in a variety of struggles in the United States, to link them to the motive battle, the struggle for a socialist Puerto Rico. The PSP contends that imperialist rule in Puerto Rico is critical to capita list rule in the United States and that revolution in Puerto Rico can both advance revolution in the US and tear asunder imperialist hegemony in Latin America: that (he Puerto Rican revolution is a major key to the American revolution.

The PSP at its recent American congress, which drew 1500 people, took no stand on international questions and tendencies in the workers movement, and stated it saw no special political tendency in the US as a vanguard. It considers “sectarianism” on the left to be the bane of radical politics. The PSP moves in areas of activity in the Maoist milieu, from Guardian forums to antiwar activity to the November 4 Coalition’s New York City workers conference.

I am not attempting, nor am I able, to predict where the PSP will go, what its ranks will do, as the Maoists regroup. What should be kept in mind is that the PSP is the major revolutionary party – one might say nearly unchallenged – in Puerto Rico, and holds much sway, prestige and impact in the radicalizing layers of Puerto Rican youth in this country. The new Maoists are not unconscious of either the PSP’s role, nor its political ambivalence on international questions. States Guardian writer Roberta Salber (before the PSP New York congress):

“The PSP’s role in this country is a complex issue. On the one hand, as the struggle for the liberation of the third world intensifies, the contradictions within the US are heightened ... on the other hand, what is to be the relation of a Puerto Rican revolutionary party to the North American left? Clearly, the PSP cannot pretend to assume the sole leadership role. What it can do, however, is participate in the concrete formation of a vanguard party in this country and be a part of that party.”

In mid-March, the PRRWO dissolved its bimonthly paper, Palante. Its circulation had declined to, according to the PRRWO, “a few thousand.” The organization stated its paper had outlived its usefulness and committed itself to, in the future, “. . . join with others in a common effort to build such a new independent newspaper – a voice that will grow louder and clearer in the coming years in its call to all persons sincerely dedicated to ending exploitation and oppression to unite, all of us unite to defeat and destroy our common enemy–the monopoly capitalist class of the United States.”

The PRRWO may have up to 150 members.

The I Wor Kuen group, based in the Chinese communities of San Francisco and New York, is a Maoist organization whose leadership appears to have close ties to RU. It publishes a twice-monthly newspaper in Chinese and English. It has appeared at Guardian forums, been in antiwar work around the November 4 Coalition and the Inauguration Day Coalition and is well known in the Chinese communities in which it operates.

The Bay Area Asian Coalition, whose leadership appears differentiated from IWK, also is politically close to RU. The Bay Area Asian Coalition has led and organized contingents in antiwar demonstrations of several thousand at given times.

IWK appears to be evolving from its community based, serve-the-people outlook, to a more consciously ideological formation, an evolution which points to its support of the creation of a new Maoist party, of which it would be part.

It may have near 100 members, with a broader periphery and base.

The BWC is in the process of politically consolidating its line. It evolved from the split in the League of Revolutionary Workers in Detroit.

The BWC has participated in Guardian forums, the November 4 Coalition, opposes the concept of a mass Black political party and opposes nationalism, basing its ideology on the liquidation of the national question into the struggle against the superexploitation of Black workers, especially Black industrial workers.

At this point in time, the BWC leadership appears confused about its perspectives. After BWC leader Mike Hamlin spoke at the Guardian forum on the new party, the organization withdrew from the forum on the national question. It stated its firm solidarity with the groups involved in the forums, its belief in the party building strategies of Mao, Stalin, Lenin and Marx, but noted its own ideological incompleteness and the need to work out its line.

An all-Black organization while being antinationalist – the BWC believes it should stay all-Black and not merge just yet to form a party in order not to abandon the undeveloped Black struggle to reformists and “narrow” petty-bourgeois nationalists – the BWC affirms the need for a multinational party. It appears foundering in the wake of that formal contradiction.

It is hard to estimate the size of the BWC, which plays a large role in the November 4 Coalition. Its work is not highly publicized. It may have between 100-200 members.

I include this more as a question. This small grouping, which at one time was vociferously anti-Trotskyist and pro-Maoist, has been mentioned in the press of the October League, which has played a role in building the Chavez-Ortiz defense committee possibly with them. I have no information other than that.

I have described, to the extent it is possible, the organized tendencies, the intermediary collectives and small groupings, and the political character of the general, unorganized milieu. This is a sizeable aggregate of radicals and is not decreasing; in fact, as the cynicism produced by a lack of understanding of the lull in activity deepens, it will continue to grow.

The crystallization of the Maoist milieu, however, will draw on other ranks for its cadre, from other radical tendencies. The two which a new party of Maoist politics might significantly affect are, in my opinion, the New American Movement and the Young Workers Liberation League.

NAM is the not-so-youth organization of a nonexistent Social-Democratic party. It was created specifically as an alternative to the YSA, seeking to revive the best of SDS without its attendant weaknesses. The energy of SDS was rooted in the period it occurred in; its ultra-leftism derived from the fact that there had not been spontaneous student rebellions for two generations. SDS became the vehicle through which the spontaneism of the youth radicalization reflected itself in its most extreme form; with the decline of that period and the necessary dissipation of the ultra-left mood, SDS could not exist. NAM could merely repeat the organizational and political mistakes of SDS without the consequent impact and publicity.

NAM is a petty-bourgeois reformist organization, fraught with internal tensions which are a product of its incorrect political line, its organizational obsolescence, and the tests imposed by a period which demands increasing seriousness from radicals who challenge the system. Part of these tensions have created a left wing, a minority of NAM, which in some areas has agreed upon the need for a democratic-centralist party.

The very pressures, both subjective and objective, which are bringing about the Maoist regroupment are breaking NAM apart. The greatest question for the left-wing elements in NAM is probably Stalin. The syrupy-sweet socialism NAM projects is indeed distant from the rhetoric and politics of the Maoists. Organized anti-Trotskyism, however, can, in the swirl of events, in the process of breakup and regroupment, emerge as a powerful recruiting tool. And the emergence of a new revolutionary party in opposition to the SWP, could be a magnet for the left-wing minority in NAM, increasing the pace of the demise of the whole organization.

The case of the YWLL is more serious. It is the hot potato in the hands of the top CP bureaucrats who organize a fight against the party’s right wing. The CP chiefs are in a tenuous situation: on the one hand, they are increasingly forced to adapt to the radicalization and its thrust against the Democratic Party, especially as the Democratic Party becomes captured by the right-wing labor tops and the anti-“New Politics” hacks. On the other hand, its left-sounding demagogy is limited by its subservience to the counterrevolutionary policies of the Soviet bureaucracy. As China contends with the Soviet Union for the diplomatic coups offered by peaceful coexistence, the CP must kindle the fires of its anti-Mao polemics. At the same time, a new Maoist party would initially, in both theory and practice, have a more “left” posture than the CP.

These factors could intensify the internal conflicts in the CP. The antinationalism, antifeminism, anti-Trotskyism and workerism of the Maoists represents no basic change for those young CPers and YWLLers whose dissent against the CP right wing is a key base for Gus Hall’s “left-wing” faction. At the same time, the CP leadership can only bend to the left so far, perhaps not far enough to satisfy the dissident layers. It is only speculation to figure if the deep, bitter anti-Chinese prejudice in the CP is strong enough to firm up the unassimilated layers of the YWLL.

Historically Maoism has thrown the CP into a frenzy. The case is even more apparent now. Recently the CP accused the Chinese leadership of importing heroin into the United States. The Guardian responded with a sharp polemic against the CP tops, urging the CP ranks to heel them. While the CP has not reneged, the Brooklyn DA has stated his own similar charges were erroneous.

The deepening of the crisis in the CP is not unnoticed by the Maoists, who seek cadre everywhere. We should realize another variant for dissident CP youth and YWLLers besides the Trotskyists is the “revolutionary” Stalinists of the Maoist stripe.

* * *

What becomes apparent, and what we are talking about, is the existence of a sizeable (1000-2000) layer of radicals organized into tendencies and organizations, local collectives, etc. (and a broader milieu whose commitment varies) which is largely white and ex-student, and draws on a significant layer of Blacks, Latinos, Asians and Puerto Ricans. It is a milieu which through the pressure of objective events in the class struggle domestically and internationally and through deliberate organization is being coalesced into an opponent force of serious proportions.

We are talking about a layer which publishes two dozen monthly papers, a variety of pamphlets, at least two theoretical magazines ( Red Papers and Proletarian Cause), engages in common political activity in the mass movements (antiwar, to a lesser extent women’s liberation, as well as strike support committees), discusses and debates its strategy internally and publicly through national tours and in forums and small groups, that has a national weekly newspaper with a circulation of 20,000, and that exists, to one degree or another in most major American cities and around most major colleges and universities.

We are not talking about a new SDS or Seattle Liberation Front, not about esoteric academic dilletantes, or a layer that can be quickly disregarded as easy-come, easy-go workerites. Rather, we are witnessing the process of the attempt to consciously rebuild and deliberately organize a new Maoist party on a national scale.

At the same time, there is a volatile character inherent in the regroupment; the dynamic of the national struggle and its effect on Black, Latino and Asian layers in the context of the Maoists’ anti-nationalism; the continuing right swing of the Chinese bureaucracy; the existence of apparent and submerged differences in the Maoist milieu on strategic, programmatic and organizational questions; the deep ignorance of the practical tasks of party building. The Maoists read only up to Lenin. Their reliance on the “thought” of Mao Tse-tung, its vagueness and idealist mumbo-jumbo – aside from concrete Menshevism – cripples the ability of the Maoists at the outset.

One could say that this milieu would form a party in spite of its politics. Unprincipled and opportunist, vacillating between ultra-leftism and class collaboration, inhibited by a self-imposed “security consciousness,” noosed by the albatross of Stalin and guided by the metaphysical axioms of the Great Helmsman, these Maoists have no easy road to party building. The possibility of new intra-bureaucratic splits and struggles following Mao’s death could also deepen the problems faced by the new Maoists.

They will tend to recruit from a conservative layer, one which corresponds to the Maoists’ uncomfortability with and rejection of the class struggle as it unfolds. That is, a layer which lacks political confidence in the ability of the proletariat to make a revolution which incorporates the potent dynamics of feminism and nationalism, a revolution which challenges the fundamental bourgeois assumptions of social and sexual life more profoundly and more sharply than ever before in human history.

Indeed, the cultivation of the Stalin myth and Stalinist theory as their raison d’être is an indicator of the intellectual and political malnutrition of this layer, a poverty of thought that reflects itself in a political insecurity and paralysis which consciously seeks out the soothing balm of power. That is, state power, tie power of Stalin in power. It believes in the mythological explanations of the defeat of his proletarian dictatorship by Khrushchev and his revisionist bandits, and the heroic reemergence of bureaucratic absolutism with a left veneer in China. That is state power that these Maoists link onto as a proof of their correctness, as a guarantee of their line, a line that has won and won big.

The principled, critical necessity for a revolutionary international; the confidence in a time-tested program and a concomitant confidence in the revolutionary capacity of the proletariat and its allies; a Marxist critique of bureaucracy and a Marxist understanding of freedom; all these are absent in the Maoists’ outlook. To fill this cavernous lack, they substitute Chinese state power and embrace its ideological foundations – Stalin and Stalinism – retracing their steps backward in cadence to the opposite momentum of the American class struggle, the increasing favorability of the relationship of forces on the left internationally, and the increasing consciousness of the revolutionary masses of the difference between revolutionists and betrayers.

These new Maoists seek continuity, embracing the disastrous Comintern policy for the Chinese revolution in the late 1920s, the purge trials, popular frontism, the Hitler-Stalin pact. Every Stalinist betrayal for these new adherents to bureaucratic power is; a link in their historical chain of justification: there are no betrayals, just misunderstood victories. There is no pattern in the “mistakes” that are admitted, but a continuity of bumblers, of those who misapplied the line, from Borodin to Browder, from Liu Shao-chi to Lin Piao. Identification of the butter-fingered practitioners of Stalinist politics, coupled with a steady stream of self-criticism and stringently applied codes of bureaucratic-centralism, will be the finishing touches of the new Maoists, giving them an unblemished claim to Peking’s American franchise and an internally logical “historical continuity” to Marx and Lenin, the “teachers” of Stalin and Mao.

One has to be ideological to link up with this movement; one must have absorbed the politics of this milieu to be organizationally assimilated by it. This is a small layer, capable of immersing itself in those politics, a limited layer, a layer expanded in the process of conservative response to heightened struggle. It is the backwash of every passing upsurge and period of action, a reflection and adaptation to bourgeois ideological pressure directed at the radicalization.

Precisely in a period of lull in activity does this backwash seem to have more vitality than it objectively does; the tests of heated action, the challenges posed by the radicalization of new and decisive layers, the emergence of new, complex tasks of analysis, intervention and party building, these will put the real size, impact, and influence of this milieu into a precise, objective context.

I do not believe we have paid enough attention to this milieu in the past, at least since its surfacing through the November 4 Coalition. That is in the process of remedy.

For now, we should not wait for the further crystallization of the Maoist forces. We should pay special attention to them, in an organized fashion. That is, we should intervene propagandistically in the process of Maoist regroupment.

While not going on a polemical binge (which would give the impression that we are fearful of this milieu, giving it undue importance), we should begin to publicly identify the organizations, their stands and activities in concrete situations, taking them on tactically and theoretically.

For instance, the Guardian has defended the peace treaty as a Vietnamese victory by claiming the Vietnamese revolution is at present a “new-democratic revolution” against imperialism, and with the extrication of imperialist forces, and over a period in time, the second stage, “for socialist revolution,” can begin. The “new-democratic” theory is Mao-colored Menshevism, nothing less, but is being revived in this milieu and the left as a whole. Theoretically we counterpose the theory and strategy of permanent revolution to it.

The RU analysis of the national question, a position of the most surreptitious antinationalism; the “restoration of capitalism” in the Soviet Union; etc., are among the many political concepts of these forces we could take on.

Secondly, we should, in the branches, deal in educationals with specific aspects of Maoist policy, from the meaning of the “united front against the super powers” (the recent Guardian pamphlet “Unite the Many Against the Few,” would be an excellent source), the role of Browderism in the CP and the role of William Z. Foster, and especially the national question, etc.

We should seek out individuals in this milieu where possible to debate us, either in forums or neutral territory, to debate contending strategies for socialist revolution, Black liberation, women’s liberation, China’s role in world politics, etc. And, where and when possible, in the looser formations, “anti-imperialist” contingents, forums, etc., assign a comrade to keep on top of events therein. Comrades should be encouraged to follow the process of regroupment in the Maoist press and branch libraries should subscribe to that press.

There are political gradations in this layer. If we can find study groups, we should seek out invitations if possible (and, if they are given, that is an indication of how lined up the grouping is) and speak at them. What will win the less hardened layers of this milieu to us is the sharpest counterposing of Trotskyism to Maoism, to the tradition of Stalinism in the international working-class movement.

The frankest and most knowledgeable discussion will be required if recruitment is to take place at all.

All of this can only have the most beneficial outcome for us: in the recruitment to our own movement through the clarifying and sharpening process of debate; in the political hardening, and toughening of our cadre in the internal process of education and the external activity.

* * *

The very political character of Maoism is, especially given the growth and solidification of the revolutionary Marxist movement, its greatest nemesis. The “permanence” of the new Maoists is as shaky as the political ideas which are the body of Stalinism. Objective events and Chinese politics can weaken and blow apart this milieu – as they have done across Western Europe and in numerous colonial guerrilla movements – quite rapidly. At the same time, the efforts of the subjective factor in history, the conscious proletarian vanguard, can aid, deepen and make more pronounced and profound those blows, putting them to the most productive use of the class struggle.

Right now the regroupment of the Maoist current is still in its infancy. The most consistent and articulate propaganda in our press, the internal preparation for serious opponents work, and the deepening impact of counterrevolutionary action carried out by the Chinese Stalinists will hopefully enable us to throw that baby out with its bathwater.

May 8, 1973