Published: n.d. [1975]

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

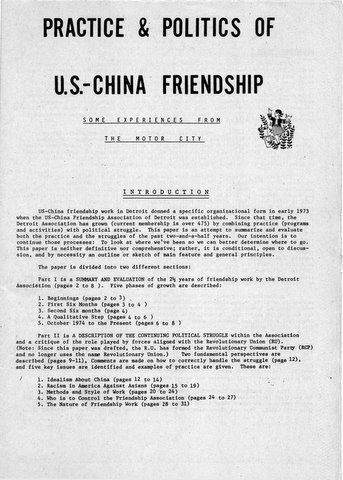

MIA Introduction: This text is part II of a longer pamphlet entitled “Practice & Politics of U.S.-China Friendship. Some Experiences from the Motor City,” published by the U.S.-China Peoples Friendship Association of Detroit. The published version states, “This paper is a draft.”

“What should be the relation of the Friendship Association to other organizations, particularly to Marxist-Leninist groups?”

“Will sectarian tendencies be a problem in building Friendship Associations?”

“How will we be able to keep the Association viable, with a broad base, including all who are interested in friendship with China?”

“What should be the class perspective of the Association – toward what groups should we gear our activities?”

“Should Associations be open membership organizations, or should they be self-selecting groups of activists?”

These exact questions were raised in December 1972 at the original meeting to found a Friendship Association in Detroit. Looking at the present state of Associations and the major issues facing us, it is obvious that the importance and timeliness of these questions continues. Moreover, during the past 2 and a half years, different answers and different responses in practice to these questions have become matters of controversy within the Association. A key feature of this struggle in Detroit has been the role of Association members who are also aligned with the Revolutionary Union (RU). The policies and practice of “RU forces” have become a focal point of struggle within the Association.

Detroit’s internal political struggles developed steadily over a period of time. During the first year of the Friendship Association, differences were raised and argued out in a spirit of “unity-struggle-unity” and the general goals of the Association seemed clear and adequate guidelines for all. As the Association grew and expanded, differences over several issues emerged which can be identified as: (1) Idealism about China and the question of whether China can .be criticized; (2) the question of racism against Asians in America; (3) The methods and style of work of the Revolutionary Union; (4) The question of “Who is to control the Association(s)?” and (5) The nature of Friendship work and the role of Friendship Associations. Each of these general areas will be discussed, with examples, below. However, we first want to emphasize some general points.

In Detroit, a pattern emerged which has tied all these various political issues together: when the issues were dealt with openly and directly, the active membership of the Association (with almost no exceptions) polarized with all but the Revolutionary Union forces on one side, and the RU forces – an isolated handful – on the opposite side. This political struggle has developed to the point where there are now two clearly identifiable, and contending political perspectives inside the Association. The two perspectives represent two fundamentally different approaches to the question of how friendship work should be conducted and how the Friendship Association should be organized. The different practice produced by these two perspectives illustrates that one can lead to a broad, active organization while the other will turn the Association into a narrow, isolated sect.

On one side, the vast majority of the Detroit Association has united around a perspective, or “line”, which calls for: (1) An open, broad, and diverse membership; (2) Independence from other political groups; (3) A real, and viable, organization; (4) Practice based on local conditions and growth based on practice; and (5) Uniting non-Chinese Americans with Chinese-Americans and Overseas Chinese. These principles have specific meanings:

First: An open, broad and diverse membership. This has important organizational implications. It means the Association must adopt, in practice as well as words, an honest and democratic style of work. It means there must be room for diversity within the Association, again in practice as well as in words. It means the active participation of members must be encouraged. Members of the Association must be viewed as activist friends of China, not as merely passive receivers of information about China.

Second: Independence from other political groups. This has been regarded as fundamental. The Association does not exist in a political vacuum; we are working in a highly political environment. The “politics of Detroit” surround us. We recognize this reality and feel that if our goal is to unite all possible friends of China, we must build the Friendship Association as an organization where all friends of China feel comfortable and are welcome. The Association must not be organizationally tied, directly or indirectly, to any other particular political organization. There must be room for all individuals to participate and subordination to no other political group. One thing this means is that Association policy and leadership must be determined on an open and principled basis. Leadership must be chosen on the basis of Association practice and decisions made on the basis of what promotes Association goals. This does not mean individuals who are members of other political organizations cannot play active and leading roles in the Association. On the contrary, if other organizations have a correct and principled perspective in working with the Association, then individuals who are members of such groups can (and do) help significantly in building friendship work and the Association. And, in fact, if done in a principled way, the contributions to the Association by individuals who are members of other political groups can draw upon their experience and perspective in positive ways.

Third: The Friendship Association has an organizational life of its own. This is closely related to the question of independence. If the Friendship Association is to grow, activists must take it seriously as an organization in its own right, with its own legitimacy and goals. It must not be seen simply as a recruiting ground or just as a mean to “turn people on to China” and then “turn them over” to some other organization(s) when they “develop”. The Friendship Association must be a place where people can work and build friendship in depth. Programs, structure, and activities must reflect this.

Fourth: Practice based on local conditions. The Detroit Association has emphasized practice; we have been “doers”. Our work has been rooted in local conditions and geared to local needs. We believe we have grown because we put practice first. After all, “where do correct ideas /and good organizations come from?” We have advocated putting practice first in building regional and national structures, and for choosing leadership.

Fifth: Unity of non-Chinese Americans with Chinese-Americans and Overseas Chinese. This relationship has been an important part of our Association and has been key to our development. It has meant mutual sharing – a living implementation of our goals – and it has vastly deepened and enriched all Association programs. Building and maintaining this unity has meant taking up, in appropriate ways, the question of racism against Asians in America.

Agreement on the above principles has united the vast majority of the Detroit Association. On most of these principles there has been little open or direct opposition. But judging by practice (by actions, rather than by words) the Revolutionary Union forces are either operating on the basis of different principles or do not see that their actions contradict what they claim as their principles. After looking at the RU’s practice in the Detroit Association over the past two years we have been able to discern an approach, or “line”, that is clearly different from the one held by the vast majority of the Association. This RU “line” is often unspoken, but nevertheless recognizable. As deduced from their actions, it discourages broad, active and open membership participation because of its sectarianism, its less-than-honest style of work, and its lack of interest in or antagonism to involving the Membership in the Association’s decision-making. As deduced from actions, the RU “line” subordinates the Friendship Association’s interests and legitimacy to that of another group. As seen in practice, and openly admitted in writing (e.g: the Hinton and Kissinger paper, “Build the Friendship Association,” which has been circulated nationally to all Associations), the RU “line” promotes structures and methods of choosing leadership that ignore internal democracy and are divorced from practice and from a broad membership. Finally, as seen in both practice and theory, the RU “line” opposes programs that are key to building and maintaining unity within the Association between non-Chinese, Chinese-Americans, and Overseas Chinese. Thus, we have come to the conclusion that there does exist, in fact, a political struggle within our Association between two fundamentally different approaches, or “lines” to the question of Friendship work.

In their most general form, the two perspectives within the Friendship Association boil down to broad or narrow interpretations of the composition, nature, style of work and role and direction of Friendship Associations. The fundamental issue is whether to build a broad, open, independent friendship movement with a correct political perspective, or whether to limit membership participation, exclude important areas of programming, and subordinate the work of the Association to the political direction of another group.

It is also interesting to note that the political struggle inside our Association increased sharply in late 1973 and early 1974. An identifiable “RU presence” in the Association developed precisely during the same time that it became clear that a national organization would be founded. Apparently the RU responded organizationally to the creation of a national friendship organization whose national center, and national influence and power, would be important to control. Our criticism here is not that the RU responded to, and worked with, the emergent Association. Our criticism is that the nature of the response was (as the examples below will show) a drive for hegemony and the promotion of an incorrect political “line”.

Friends have sometimes urged us to “raise the issues” but “don’t mention the Revolutionary Union by name”. Some have argued that directly raising the question of the RU could (1) obscure the substantive issues; (2) promote anti-communism within the Association; or (3) turn the current political struggles into a factional fight.

We are very concerned about these dangers. That is precisely why we have chosen to identify both the political positions and their principal purveyor: the Revolutionary Union. By its own actions and by its style of work the RU has made itself a substantive issue. We cannot ignore this. We cannot pretend the role of the RU inside the Association is not in and of itself one of the most crucial questions facing the friendship movement today. We need to identify and deal with the RU directly, openly, honestly. To fail to do so will only obscure the issues more. To fail to do so will allow anti-communism and genuine criticism to co-exist with no distinction made between the two. To fail to do so will continue a situation where factional politics are interjected into the Friendship Association, but are not identified as such.

We have also been told that raising criticisms of the Revolutionary Union is being “anti-communist”. We disagree. Our experience has been that this response is usually designed to avoid dealing with the substance of valid criticisms. It is a dodge – a smokescreen – to obscure genuine problems. We are concerned about anti-communism within the Association. It can be a problem, and it should be combated when it appears. However, our experience in Detroit has been that the greatest promoters of anti-communism within the Association have been the RU people themselves. For example, they claim they do not function as a political group within the Association; they pretend that they are not part of a unified political organization. By denying that they operate with a common political line and a political purpose, by pretending the obvious does not exist, they continually reinforce the “J. Edgar Hoover” anti-communist stereotype of deceitful and dishonest communists who work within organizations for ulterior motives. Thus, anti-communism is generated by the RU because they, declare themselves to be communist while at the same time refuse to work in the Association in an open and principled manner. The resulting spectacle leads some people to the mistaken conclusion that the way the RU works in the Friendship Association is the way communists work in mass organizations. Finally, the RU’s refusal to distinguish between genuine criticism and anti-communism simply makes it more difficult to identify, and combat, genuine anti-communism.

Let us make this clear: We believe all genuine friends of China should be included within the Association. We also believe all Association members, including RU members, have the right to argue and organize for, promote, and caucus around their political positions in principled, open, and honest ways. If the RU is serious about combating anti-communism, it should function openly, honestly, and above-board within the Friendship Associations. It should depend upon winning people to its positions on the merits of its practice. But this, as we shall note below, seems to be just the opposite of much of the RU’s style of work. If the RU worked in a principled manner it would find many allies in struggles against anti-communism within the Association. It is unreasonable, however, to expect people to set aside legitimate criticisms simply because the RU chooses to label as “anti-communist” all criticism aimed in its direction.

We also want to state how we believe the political struggle should be handled. We believe political struggle can be positive; it can move work forward. There is an understandable fear among some people that the struggle will become senseless squabbles, vicious bickering, or factional fights among various outside political groups interjecting their differences into the Friendship Association. These are real dangers. If we don’t handle the struggle correctly, it could definitely harm Association activities. If we ignore the struggle or try to sweep it under the rug, we will virtually guarantee that the work will be harmed.

What, then, is the correct way to handle the struggle? First, we believe it should be identified, put directly on the table for all to see, and dealt with head-on. Second, it should be approached in the spirit of “unity-struggle-unity” – going from one level of unity, through struggle, to a new level of unity. Everyone should understand that broad areas of unity do exist and provide a basis, if we deal with each other honestly, for much friendship work to be done.

We approach these struggles in the following spirit:

The only way to settle questions of an ideological nature or controversial issues among the people is by the democratic method, the method of discussion, or criticism, of persuasion and education. (Mao Tse-tung, “On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People”)

The following discussion of issues involved in the struggle with the Revolutionary Union is based on the way the struggle has taken place inside the Detroit Association. We do not expect our struggle to be identical with that of other Associations. However, we are impressed with the similarity and consistency of the underlying fundamental questions. Timing, priority, and particular features will certainly differ. The basic issues, however, are unsurprisingly similar.

The first struggle to emerge in the Detroit Association was rooted in the question of “idealism” toward China. We use the term “idealist” to describe a person who thinks that the revolution in China has been completely victorious and that, in effect, it is over and the only problem remaining is for China to develop economically. The idealist paints a picture of China as a country where all social problems have been solved and the people will always be victorious.

In the Detroit Association the issue of idealism was first raised indirectly. Precisely because they were concerned about frequently encountered romanticism and myopic views of China, some Association members suggested there was room inside the Friendship Association for “criticism” of China. A discussion paper was circulated which included this question of “criticism” in a larger discussion of the nature and direction of friendship work. Since people of different viewpoints worked within the Association, the paper argued, it seemed inevitable there would be different analyses and opinions on various aspects of China. Friendship, as a basis of unity, did not necessarily mean one had to agree with all of China’s policies or believe that China had solved all of its problems. Thus, the question was raised: should there be room within the Association for principled critical views of China? (From the beginning it was clear that the kind of criticism being considered was principled criticism, i.e., within the framework of building friendship, done in the spirit that the Chinese use of “unity-criticism-unity” and “curing the illness to save the patient.” As the paper quoted from Mao Tse-tung, “If we have shortcomings, we are not afraid to have them pointed out and criticized, because we serve the people. Anyone, no matter who, may point out our shortcomings. If he is right, we will correct them.” Examples were given of what was meant by principled criticism by noting that almost every speaker the Detroit Association had sponsored had raised some criticisms. Each speaker had discussed and analyzed what he or she considered shortcomings and weaknesses of the new society. In doing so, however, they had always made clear the overall context of progress and friendship abundantly clear. (Speakers at that time had included Carmelita Hinton, Ruth Sidel, Gerald Tannebaum, Hsieh Pei-chih, Ann Tompkins, and Maud Russell). It was also noted that many newsletter articles had such characteristics, and that several books on the literature table had contained critical analysis and frank descriptions of problems and shortcomings (such as the books of William Hinton, the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars book, or Ruth Sidel’s books). This, it was made clear, was the kind of criticism and frank analysis meant by those arguing that criticism could play an appropriate role in friendship work.

The concern that there be room within the Friendship Association for these types of views came from direct experience. An idealist tendency, which wants to outlaw from the Friendship Association any kind of frank analysis of China did (and still does) exist. For example, some members of the Detroit Association had been told (by individuals associated with the Revolutionary Union) that when they spoke about China they should not describe any weaknesses. RU spokespeople argued, in private, that if one saw safety problems in factories, or encountered male chauvinism, it should not be mentioned publicly. Such “public criticism”, it was argued, would play into the hands of China’s enemies and therefore should not be openly discussed. Similar idealist comments were aimed at some of the speakers the Association had sponsored. Such overt idealism, however, was not the principal way idealist tendencies raised their heads. The question of “criticism” was consciously diverted and used politically.

In late spring of 1974, minutes from a meeting of the Provisional National Steering Committee of the USCPFA were published and circulated nationally with three addendums: (1) An excerpt from a Detroit discussion paper. The paper had raised many questions about friendship work, among them the question of principled criticism. But only the section on criticism was excerpted. (2) An article from a Detroit USCPFA newsletter on the topic of China and the World Bank which included critical remarks, some principled, some unprincipled, about China. (3) Excerpts from a response to the above Detroit discussion paper (not to the article) by someone from another Association. All three pieces were yanked out of context and the effect was to make it look like the Detroit Association’s first concern was to-criticize China.

The careful arrangement and distribution of the excerpts certainly were not accidents. To date, we still do not know who was politically responsible for making these selections. Neither we would guess, was it an accident that they were published without any consultation or inquiry made to see what members of the Detroit USCPFA might think of the accuracy of the excerpts and the use of the newsletter article. Such an inquiry would have revealed that a response to the newsletter article had been published in a subsequent issue of the newsletter and that local evaluation and criticism of the article was taking place. But cast in this contrived context, the newsletter article on the World Bank soon was being touted throughout the country as an example of what Detroit meant when suggesting there was a role within the Friendship Association for “principled criticism”.

Some people characterized the article as “full of hate” for China (an incredible assessment of the article regardless of its genuine mistakes). The Detroit Association was even labeled as having “Trotskyist influence”. News about this “attack on China” in the Detroit newsletter travelled the grapevine incredibly fast. However, news did not seem to travel as fast when the author stated publicly, in self-criticism, that the article contained mistakes, explained how they were made, argued that it was not an “attack” on China, and said that to use it to attack policies of the Detroit Association was unjustified.

While debate over the question of “criticism” raged – and over what was and what was not an example of “criticism” – no one admitted to being an idealist. But such tendencies clearly existed. The World Bank article provided idealists with a convenient smokescreen to avoid dealing with the real issue. However, it was clear that those who harbored idealist principles were also those who howled the loudest when it was suggested that principled criticism had a place in Friendship work. They refused to distinguish between unprincipled and principled criticism and argued that any “public criticism” was wrong. They never explained what this would mean for speakers, newsletters, literature tables, or the diversity of membership within the Association. A campaign to ban “public criticism” was led by the RU forces in the Midwest Region and a resolution which called for a blanket ban on “public criticism” was passed at a Midwest Regional Conference in July, 1974. Idealist tendencies were apparent in the arguments for the ban. For example, in the Midwest, one idealist statement from RU quarters conjured up this straw man: “Who in the association has such a firm grasp on the objective situation throughout the world that they are in a position to lecture (our emphasis) the Chinese?” The same RU forces also tried to characterize the Detroit Association as “using the Friendship Associations as a platform to raise doubts in the minds of the American people about the progressive nature of Peoples China,” another incredible charge rooted in self defensive idealism.

Within the Detroit Association the effort to sidetrack the real issues – room for principled criticism and the need to guard against idealism – did not work. The specific newsletter article on the World Bank was thoroughly reviewed, analyzed, and criticized by the local Steering Committee. Out of our Steering Committee’s discussion,, we developed guidelines to be used in judging whether criticisms are principled and within the framework of Friendship work: (1) Who is raising the criticism? A friend? (2) Why is it being raised? To help correct mistakes? (3) How is it being raised? In a timely and friendly manner, when it will help? (4) Is it based on facts, on investigation, and not on speculation?

It was felt that everyone needed to learn to distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate criticism, rather than hiding their heads in the sand and banning all “criticism.” If we learned to distinguish, we then would not be afraid of ”criticism” and would see that when handled correctly, criticism was not antagonistic to building friendship.

Keeping room within the organization to raise principled criticisms was also viewed, in the Detroit Association, as a matter of organizational integrity. A blanket ban on criticism, we felt, would start us down the road of limiting our activities and programs to just those who agreed with China. We considered several questions: What kind of unity would be preserved inside our Association if we recruited members on the “basis of our broad statement of principles, but in practice limited our programs, speakers, newsletters, literature, and other activities to more narrow, and specifically uncritical, appraisals of China?

We asked: What kind of people would stay and participate in an organization which had glaring discrepancies between its goals and its practice? We asked: Would a posture” of banning all criticism help build our Association or would it narrow it? We asked: Why were some people refusing to distinguish between principled and unprincipled criticism, and why did they wish to ban indiscriminately all criticism instead of dealing with how, and in what ways, criticism could play a constructive role?

Answers to these questions led us back to the basic problem of idealism within the Association. It became clear that idealist errors were at the root of the opposition to dealing with the question of principled criticism. If implemented, this idealism would narrow and inhibit legitimate friendship work. A major contribution to the debate on these questions was a paper, “On How to Talk About China”, which was circulated to the membership in early 1975. The paper described three different approaches to talking about China: academic objectivism, idealism, and dialectical materialism. Giving concrete examples, the paper showed how academic objectivism and idealism would narrow and harm friendship work, and that the whole question of criticism should be dealt with in the context of what it meant in practice rather than abstractly labelling it as either appropriate or out of bounds.

Thus, the debates regarding “criticism” actually came from a basic question of idealism. We believe idealism is a genuine problem and that it can harm our friendship work. We believe it was an idealist error that allowed RU forces to conceive of and promote the 1974 Midwest regional ban on “public criticism”. The struggle on the issue of idealism will continue undoubtedly taking on new forms. It is a struggle that strikes to the heart of how friendship work should be carried out.

In August 1974, the Steering Committee of the USCPFA of Detroit passed the following resolution:

Resolved, that the USCPFA of Detroit affirms its belief that educating people about the legacy and presence of racism against Asians in America, and against Chinese-Americans and overseas Chinese in particular, is a part of building friendship between the people of China, and the U.S.”[1]

To most members of the Detroit Association, the need to challenge racist myths and stereotypes seemed obvious. How could friendship be built if a base of mutual respect and understanding did not exist?

What was obvious to most, however, was not obvious to all. Individuals aligned with the Revolutionary Union openly opposed the resolution and related programs. (It should be noted, however, that the RU’s position on this question has, in Detroit, been an “on-again, off-again” affair. What is the basis for concern over this question? Why has it become one of the most controversial issues of friendship work? Let us look at some of our concrete experience in Detroit.

The issue of racism against Asians has become one of concern with the USCPFA of Detroit because it has come from practice. It is not an issue we raised abstractly. We encountered racism in our work, and it interfered with building friendship between the Chinese and American peoples. Examples occurred at the Friendship Association-sponsored booths at the Far Eastern Ethnic Festival and at the Michigan State Fair.

The booths were successful, well-received and proved to be tremendous outreach activities. But at the booths we also encountered the realities of racism against Asians through taunts and remarks, some hostile, some intended to be “funny”: “Ah-so!” “Chop-suey – chop, chop!” “Kung-fu” (with appropriate grunts and shouts); or theatrics involving pulling the eyes to make them look “slanted”. Other examples could be cited: Some delegates on Friendship Association trips to China have been asked by others, with well-meaning “humor” to “take my laundry” or “bring back some chop-suey”. Or: Association speakers, during their slide presentations on China, have been asked how they could tell Chinese people apart because “they all look alike”. Or: The day our Friendship Association sponsored a Children’s Fair about China, the Association office received a harassing phone call from someone using a gross, fake “Chinese” accent in a blatant racist manner.

We do not want to exaggerate these instances or blow them out of proportion. We do not think, as was suggested at a recent Midwest regional meeting, that we live in a unique city which, unfortunately, is filled with racists. On the contrary, we think in Detroit, as elsewhere in the United States, there exists a deep reservoir of good will toward the Chinese people. The success of our several years of friendship work has demonstrated that fact. But the presence of racism is also a reality.

If other Associations have not yet encountered this racism in their work, we believe it is probably because they have either: a) Not yet developed broad outreach programs which get out into the general population, or b) They have not yet learned how to identify such racism when it arises. We believe everyone should learn to identify such common stereotypes as:

1. The “inscrutible oriental”. Asian people, this Implies, are not like “us”. You can’t understand them. If you can’t understand a people, you can’t trust them. This plays right into the distrust and misunderstanding of the People’s Republic of China and its people.

2. Kung-fu. The Kung-fu cult which is spread by the mass media portrays Chinese people as feudal and militaristic. The glorification of the martial arts glorifies the values of feudal China, which Chinese people in America and in new China are struggling against.

3. Chinese people are opium smokers and drug pushers. This attack on Chinese people in America helps spread the myth that China is the source of heroin in this country.

4. Chinese people in America just stick “with their own kind”. This justifies the false idea that China is anti-foreign, anti-American, and that its foreign policy is chauvinist.

5. Chinese people as passive, the model minority. Life is not valued in the Orient. This myth can be turned into a basis for saying that people in China don’t really like their social system, they just accept it; furthermore, since they are passive and “naturally” hard workers, China’s advances are due to cultural peculiarities rather than due to the masses of Chinese people consciously taking up the building of a socialist society.

One of the first steps in dealing with this reality of anti-Asian racism is to educate our entire Association membership – to make sure all members can identify and combat racist attitudes toward Asians whenever they encounter them. The victims of racism know what that racism is like; others, whether they are purveyors of that racism, ignorant bystanders, or sympathetic comrades, do not automatically understand it or know its nature. Thus, the Association must actively and openly promote that learning process through concrete programs. The methods we suggest for handling internal manifestations of racism are discussion, criticism, persuasion, and education. We stress the slogan: “Unity, criticism, unity”.

The need for internal education on this subject was illustrated by a graphic in the program of the Second National Convention of USCPFA’s. Included in the program was an ad with a small drawing of a man pulling a rick-shaw. The ad was for a travel agency and the drawing intended, probably, as humorous. However, someone obviously overlooked the fact that the rick-shaw now symbolizes a form of degradation and reinforces such stereotypes as the Chinese being “passive” and not placing value on human life.

Furthermore, one of the basic principles, and one of the strong points, of the Detroit Association, has been the unity of non-Chinese with Chinese-Americans and Overseas Chinese in the common goal of building friendship between the U.S. and Chinese peoples. (About 16% of the membership of our Association is of Asian heritage.) This has been nothing less than a living manifestation of our goal and has enriched and deepened all Association activities. This unity can exist and grow only if we all undertake the common struggle to combat racist attitudes and stereotypes wherever we encounter them, externally or internally (within our membership).

To date, our work around the question of racism has been educational. Our practice has been mostly in the form of newsletter articles (6 articles in 25 issues of the newsletter) and an internal educational seminar on the topic. In no way has our other work suffered; other activities have increased and membership (now at over 475) has grown. Actually, Our practice in dealing with racism needs improvement, such as: continued and improved attention to the topic in the newsletter; additions to our literature tables of appropriate materials; increased vigilance to chauvinist attitudes cropping up within our own ranks; and other educational programs as judged appropriate.

There are several arguments stating that Friendship Associations should not deal with the question of racism against Asians. At one time or another, all have been used by RU forces. We would like to clarify our feelings about these arguments.

First, it is argued that racism against Asians and Chinese people in particular is a “domestic issue” and therefore outside the boundaries of US-China friendship work. We cannot see the issue of racism against Asians and the building of US-China friendship as two separate and unconnected issues. They do not appear separate or unconnected when we encounter racism in our actual day-to-day friendship work. Racist myths and stereotypes (e.g.: Chinese people are “mysterious” or Chinese people are “clannish”) do not distinguish between sides of the Pacific Ocean. Arguments which tell us racism against Asians and the building of US-China friendship are two separate and unconnected issues ignore the real conditions of the real world, divorce practice from reality, and in the end prevent us from dealing with the problem in any way.

Second, it has been argued that if we take up the question of racism in America towards Asians we will expend too much time and energy in this area and harm other areas of programming. If we take up this issue, some argue, it will soon overshadow other work or lead us down the path to dealing with other issues which are clearly “domestic” issues. This argument is a straw man.

We think our practice in Detroit shows that this issue, when taken up, need not be misused. It has been a part of our work – an integral part’. At the same time, we have not taken up purely domestic issues; we have not turned the Friendship Association into an organization focused on domestic questions. We have looked at issues and events and judged which are appropriate to our friendship work. We feel that in dealing with racism, we must do so within the context of our particular organization, that is: We deal with racist attitudes as they directly affect US-China friendship. We are not suggesting that we take up questions of democratic rights of Asian-Americans or other issues specific to the Asian community in the United States, although we recognize that our interests may at times overlap with those of Asians struggling for full equality in this country. In terms of the Friendship Association, our goal is clearly defined: Our aim is to identify and challenge those ideas held by Americans which blind them to the facts about China, to isolate and destroy those prejudices which keep people from recognizing that the people of China are our friends.

Third, some have argued that anti-communism (and not racism) is the root cause of the anti-Chinese attitudes we have encountered. This argument begs the question. We recognize that anti-communist attitudes exist and are a barrier to building friendship with the people of China. But the genuine existence of anti-communism does not eliminate the just-as-genuine existence of racism. Racist feelings toward Asians, including Chinese, existed long before the Chinese Revolution of 1949. Now anti-communism and racist expressions are often intertwined, for example, in the stereotype of the Chinese people as “a sea of blue ants”. Both attitudes must be dealt with because both are serious inhibitions to developing understanding and friendship with the people of the People’s Republic of China.

Fourth, some people have also felt that actual programs designed to educate the Association membership about the nature of racism against Asians are counter-productive, that such programs create disunity. They feel that these programs – like the Detroit Association’s 1974 seminar on “Racism and Stereotyping Against Asians in America” – contribute to the problem rather than help solve it. We think the fear of such programs comes from an incorrect idea of how to handle the problem of racism and a fear of facing problems honestly. Problems do not go away when you ignore them; we should not deal with racism by trying to sweep it under the rug. Genuine friendship is built in mutual respect and understanding, and that includes the frank exchange of views and attitudes. Dealing directly with racism is the best way to build deep and long-lasting unity.

One method our Association used to explicitly deal with the issue was to organize an educational seminar, as part of a larger seminar series, on “Racism and Stereotyping Against Asians in America.” The seminar was held in December 1974, and was aimed primarily at non-Asian members of the Association, with the goal of familiarizing them about the characteristics of racism toward Asians. The seminar was presented by an Asian-American student group, some of whom were members of the Friendship Association.

Dramatizations and historical readings were used to convey both the depth of the racism and also the depth of the response to that racism on the part of its victims. Reaction to the seminar was quite positive, and many members of the Association felt they would be able to do better friendship work because they were now more able to identify racism and stereotyping. RU forces, however, argued against holding the seminar both before and after it was held. Dealing with the issue explicitly and directly, as was done in the seminar, they said, was divisive and a “guilt trip”. They found offensive some sections of the seminar which illustrated the nature and intensity of responses to racism by Asian-Americans, but they did not seem to find offensive the materials used as actual examples of racism against Asian-Americans. Finally, they argued that when racism was occasionally encountered in the course of friendship work it should be dealt with (“confronted”) right then and there, and only then and there.

Fifth, a more recent RU response to the question of racism has been to try and sidestep the issue. They now argue that we need not take up the question because in the course of our friendship work we “naturally” destroy racist myths. To be sure, the thrust of all our work is building friendship, in and of itself, is a strong antidote to racist attitudes. But we have found we need to go beyond that. In addition to implicitly countering racism by presenting accurate information on China today, we need to explicitly deal with racism by attacking its concrete expressions directly. Thus, it is necessary to do education about the legacy and presence of racism as a part of building friendship. This is necessary because racism toward Asians and Asian-Americans can and does affect our friendship work.

Thus, in practice, the RU position boiled down to saying that: 1) On the one hand, racism should be “confronted” when it was encountered, but 2) On the other hand, programs to enable the membership of the Association to identify racism and stereotyping were inappropriate, divisive, and unnecessary. Such inconsistency, we believe, stems from the RU’s basic opposition to dealing with the issue in the first place. Let us give another concrete example. The true nature of the RU’s position on this question, and the mistakes their position can lead to, were seen in a struggle we had within our Association regarding a Children’s Fair about China held in December 1974. The specific struggle was over whether to include as part of the fair a demonstration of Tae Kwon Do, a form of Korean karate. The struggle developed as follows:

During sessions of the work committee organizing the Children’s Fair, a suggestion was made to include a karate demonstration. At the time, several weeks before the fair, no one on the committee gave the matter much thought; one person, an RU activist, volunteered to contact a group she knew to put on the demonstration. This was approved. (With hindsight it can now be seen that at this time the propriety of the demonstration should have been questioned. The fact that it slipped by without serious discussion perhaps is an example why we all need to continually educate ourselves on this question.) Thus, initiated in a casual way the karate demonstration was not mentioned again in the work committee until the week before the fair. But when it was mentioned a few weeks later several new members of the committee, Asian-Americans, raised strong objections. Heated and intense struggle took place and some mistakes were made in the struggle which intensified feelings (e.g., one person called another a “honky”) and created misunderstandings. After listening to the objections, particularly those raised by Asian-Americans on the work committee, most of the committee members felt the karate demonstration should be cancelled. RU forces, however, said the demonstration should continue as arranged, and thus the whole dispute was brought to the Steering Committee for resolution.

At the Steering Committee meeting, two distinct positions on the karate question were presented. Those objecting to including the Tae Kwan Do demonstration (which included all the Asian-Americans working on the Children’s Fair) argued that:

(1) The demonstration promoted a negative stereotype, a la Kung-fu and the “mysterious Oriental”. This was particularly true because of conditions in the U.S. created by the Kung-fu TV series and the Bruce Lee movies. (2) Tae Kwan Do was a form of Korean karate, and what reason was there to include Korean karate in a Children’s Fair about China? Why, particularly considering that one of the characteristics of racism toward Asians is a failure to distinguish between the different peoples and cultures of Asia. (3) The particular type of karate involved, Tae Kwan Do, did not represent the type of martial arts’ practiced in China today. For example, the competitive and violent aspects of Tae Kwan Do (breaking boards and bricks and free-fighting) are not part of modern Chinese martial arts such as Wu Shu. (4) Even if an invitation had, in good faith, been extended to a group to put on the performance, the political impact of the demonstration in the context of the fair had to take precedence and, unfortunately, “putting politics in command” meant cancelling the demonstration.

It should be noted that objections to the Tae Kwan Do demonstration had to do with the specific context of the program, not to the nature of Tae Kwan Do or karate itself. In fact, at least four of the individuals arguing strongly against the demonstration had themselves studied Tae Kwan Do.

Arguments for the Tae Kwan Do karate demonstration, put forth by RU forces, included: (1) We extended an invitation to another group on good faith and to withdraw it would create ill-will; (2) While Tae Kwan Do is not exactly like Wu Shu, it is the closest thing we can get at the moment and thus we should proceed; (3) karate demonstrates the militancy of the Chinese people and we should include examples of that militancy in our programs; and (4) Tae Kwan Do is like the martial arts of old China, and thus what we should do is give an introduction explaining the difference between martial arts in old and new China, and then proceed with the demonstration.

The Steering Committee voted 9-1 to cancel the Tae Kwan Do demonstration on the basis that it promoted racist and negative stereotypes within the context of the particular event.

It is instructive to look at what the RU position on the issue of racism meant in practice. In practice, their position allowed for an incredible indifference to a concrete manifestation of racism and stereotyping, even after such stereotypes were pointed out to them. In this instance they actually argued for an activity which in its specific context promoted racist stereotypes and in its organizational Impact threatened the unity of Chinese-Americans and non-Chinese within the Association. While there were undoubtedly other factors motivating the RU’s behavior – such as their relationship with the group invited to give the demonstration – the fundamental problem of their approach was their incorrect understanding of the issue of racism and its relation to friendship work.

The issue of racism has been debated on the regional and national level during the past several months. It has become apparent that Detroit’s position on the question has been misunderstood and misinterpreted. Perhaps we are partly responsible for this and we need to put forward our views more clearly. However, it is also clear that there exists an effort to deal with the issue by painting false pictures and by attacking straw men. For example, in their opposition to dealing with the issue, RU forces have accused the Detroit Association with trying to force the question onto other Associations and of putting it as primary in Friendship work. Neither characterization is true. We understand that different Associations carry out their work in different conditions. We know the issue will manifest itself differently in different Associations. We have also always viewed dealing with the issue of racism against Asians in America “as a part of” Friendship work. We have never characterized the issue as “central” or “primary”, as has been attributed to us. We have, rather, argued that practice shows us that it is an inseparable part of Friendship work, and that the specifics of how it should be approached – what are correct and what are incorrect ways to handle the problem – should be matters decided through more practice, more investigation, and principled struggle. What we oppose is the position that says dealing with racism toward Chinese is separate from Friendship work and should not be dealt with directly.

This issue is complex, and must be dealt with in terms of specific situations and specific conditions. But it is a genuine problem. The existence of racism toward Chinese as part of a general racism toward Asians is a concrete barrier to building friendship. It cannot be ignored. Let us not retreat from its complexities. Let us meet the challenge in the spirit of building genuine and lasting friendship between the people of China and the United States.

Some of the sharpest areas of struggle with RU forces in the Friendship Association have been over their style of work – over such basic issues as honesty, openness, and principled methods of struggle. In Detroit, as elsewhere, many Association activists are coming to the conclusion that “The RU people ... are completely unprincipled. They will lie, cheat, go to any lengths to have their way ...”[2]

We know these are harsh words. We do not raise them lightly. We raise them not to condemn, but in the hope that they will help move the RU to some critical self-evaluation. Consider the examples listed below, drawn from our experiences in Detroit, and you will see why we feel these criticisms must be raised.

In June 1974, a Midwest Activist Delegation visited China. Four Detroit delegates were selected by the local Association, following an interview and selection procedure. However, Clark Kissinger, a proponent of the RU line from Chicago and then Midwest Trip Coordinator for the regional association, took it upon himself to ask a leading member of the Revolutionary Union (also from Chicago) to run a “security check” through RU channels on one of the Detroit delegates. The reason Clark decided a “security check” was needed was that the delegate had noted on his written application that twenty years earlier he had joined and then quit a Trotskyist organization. Following Clark’s request to the RU, and independent of Association channels, local RU people in Detroit were contacted and asked to run the “security check”. A Detroit RU person contacted the delegate involved and initiated a discussion of his political views on the pretense of being interested in his former work in some of Detroit’s automobile factories. This “check” was then brought to the attention of the Detroit Association’s Steering Committee Coordinator by the RU, but characterized as having been initiated by the Chinese. The Detroit Coordinator investigated and found that (a) it was not the Chinese who had initiated the “security check” and (b) that in fact the Chinese had earlier approved the individual involved as part of another trip which had never materialized. However, when this was pointed out to the Detroit RU people they suddenly developed a bad memory and said perhaps they had “misunderstood” about the Chinese originating the “check”. They then asked that the whole thing be kept “between us” for “security reasons” and objected to it being taken to the local Steering Committee for discussion.

Once the dust settled around the incident, the following facts became clear: (1) An RU activist, occupying a position of responsibility in the Association’s regional structure, turned to an outside political group (the RU) to run a “security check” on a delegate screened and selected by a local Association for an Association trip; (2) the local Association was not contacted when questions arose in’ the mind of the regional trip coordinator about a local delegate; (3) The Detroit RU people misconstrued (perhaps not intentionally) the request for the “check” as having come from the Chinese, and when confronted with the fact that it didn’t, they would still not admit that it had been originated entirely by Clark Kissinger; (4) The Detroit RU people did not want the elected leadership of the local Association, the Steering Committee, to know of the incident and wanted to keep the whole thing quiet because of “security reasons”; and (5) They never raised real or legitimate security questions; the whole episode was rooted in political questions ,(which had been dealt with by the local Association) of what someone’s political beliefs had been twenty years previously.

The incident has been debated locally and regionally, and criticisms were raised with the RU people involved. They were not accepted. To date they have defended the propriety of the action. Individuals associated with the RU still maintain that it was appropriate to “consult” opinions from “independent sources”. There has been no self-criticism, no agreement that it should not have been done, no indication that they believe it wrong to have involved an outside group in the internal affairs of the Association, and apparently no understanding of how the action reeked of sectarianism, dishonesty, and elitism. They have never dealt with the implications of their actions and how they affect the Friendship Association. That is, their actions clearly implied that individuals applying for Friendship Association trips to China might have to meet the approval of the Revolutionary Union. The actions also gave the RU, as an outside political group, a special relationship to the Association by their running “security” checks on individuals for the Association. It is obvious such practices narrow the scope of the Association and drive away from the Association anyone who does not think it appropriate that they be screened, for a Friendship Association tour, by an outside, partisan political group.

Relations between the Ann Arbor and Detroit Associations have involved both unity and struggle. In May 1975, an incident occurred which many in the Detroit Association considered highly unprincipled and politically opportunist and which involved the RU’s role in the Association.

A leaflet turned up at a Detroit Association dinner on May 17th, advertising a May 23 program in Ann Arbor, sponsored by the Ann Arbor, USCPFA, with a speaker named James Coates who was identified as “of the US-China Peoples Friendship Association of Detroit”. (Our emphasis) Most members of the Detroit Steering Committee were puzzled because they had never heard of James Coates. No one knew that he was speaking publicly in the name of the Association. Investigation revealed that: a) James Coates was a member of the Detroit Association, having sent in dues in October 1974. However, he was not an active member. To the best of any recollection, he had never participated in any Association program, meeting, or activity, b) James Coates was a member of the Revolutionary Union, having previously spoken under that designation at an event sponsored by the Ann Arbor Association about six months previously.

When the propriety of using the name of the Detroit Association was raised with the Ann Arbor Association, their response was: Since James Coates was a formal member of the Detroit Association, it was appropriate to designate him “of the USCPFA of Detroit” regardless of the nature of his relation to the Detroit Association. They did not feel they needed to communicate with the Detroit Association organizationally in order to designate the speaker as they did. Furthermore, they added, the Ann Arbor Association wanted to get rid of its image of being an RU-oriented group and thus didn’t want to identify their speakers as being from the Revolutionary Union. They said that they felt using the designation of the Detroit Association would help with this problem of their image, even though the speaker had appeared publicly under their sponsorship as an RU spokesperson only a few months earlier. The actions of the RU members and their friends – using the USCPFA of Detroit label for a speaker who had recently spoken in the name of the RU – had an obvious effect. It meant that anyone with a memory of more than a few months would wonder why a Friendship Association would openly sponsor an RU speaker on one occasion and then sponsor the same speaker again but identify him only as being from another Friendship Association. The effect, at a minimum, is to raise questions in people’s minds about the honesty and integrity of the Association.

When this incident was discussed in the Detroit USCPFA Steering Committee, an RU activist admitted weakly that “perhaps” the designation was unwise, but then emphasized that criticisms of the RU had been raised in an inappropriate manner. (The specifics of this counter-criticism were also at variance with the facts of the situation.) This was a response many have found to be typical of the RU when criticisms are raised, i.e., when criticized, the RU counters with accusations against those raising the criticisms and sidetracks discussion of the real substantive issues.

An unfortunate incident occurred during the March-April 1975 Midwest Friendship Tour of China – an incident arising when two delegates from Detroit gave an inappropriate gift to the group’s Chinese interpreters. The particulars of the incident are not at issue here; suffice it to say that it was a serious incident and that it was dealt with as such both by the group during the tour and by the Detroit Association’s Steering Committee after the tour returned.[3] After analysts of the incident there was unanimous agreement – at least at the time – that there had beer no political motives involved in the giving of the gift and that it was not deliberate provocation. However, during the process of analyzing the incident, members of the Detroit Association began to hear rumors (from other cities) that the Detroit delegation had included “CIA agents” or the like. A tour participant from Iowa, an RU supporter, wrote a highly subjective account of the tour which personally attacked several of the Detroit delegates and misconstrued Detroit Association policy. This account was circulated at a Regional Steering Committee meeting without prior notice and thus without any opportunity for those accused to answer the charges.

This version of the incident was then included in a memo circulated to the National Tours Committee and Liaison Office by Clark Kissinger. This memo also tied the incident to the Detroit Association’s policy on pre-trip preparations and thus tried to discredit the Detroit Association by innuendo. Such distortions were both incorrect and opportunist. But even more important, while Clark Kissinger saw fit to send the memo throughout the country, he never sent a copy to Detroit or informed the Detroit Association of its existence. Thus, an incident that was serious, and certainly needed careful analysis and evaluation, was used as a “political football” by the RU forces. They conducted their “struggle” behind the backs of the Association and the individuals involved, and it became apparent that they were more concerned with their factional purposes (i.e., discrediting the Detroit Association) than dealing, in an open and honest way, with the real substance of the incident.

The RU and their friends once again acted in a way to contradict any protestations of building a broad or open Friendship Association. They treated those who had made an error (in this case, everyone agreed that an error had been made) as if they were not interested in building friendship with the Chinese. But such insinuations – even to the extent of being CIA agents – were never done so that they could be answered directly. The charges and allegations against the Detroit Association were made behind people’s backs. Once again, the RU’s actions tended to narrow the Friendship Association to their friends and followers.

On several issues the Revolutionary Union forces have displayed an inconsistency in practice and policy that can only be explained by their placing expediency above principle in pursuing their particular goals. In short, their work style has consistently included a “political dishonesty,” a failure to put forward their views in open, honest, and above-board ways. For example:

Take the question of racism. The RU’s opposition to dealing with the question of racism has, in Detroit, been an “on-again, off-again” affair, apparently the result of opportunist maneuvers rather than real changes in their position. In August 1974, the RU’s opposition to the resolution on racism was open and direct; they voted against the resolution in the Steering Committee. In January 1975, when the same resolution was brought to a general membership meeting (where they would have had to publicly defend their views), RU forces said they had “changed their mind” and supported it. Shortly thereafter, at a regional meeting, the same individuals reversed their position and joined with other RU forces to openly, and somewhat frantically, oppose dealing with the issue as part of friendship work. Later, when support for their opposition to dealing with racism began to erode on the regional level, they again modified their stand. When asked about such inconsistency on the issue, their answer was that their position had “developed”. Why all the fancy footwork? Does it indicate real changes, “development” in their beliefs, or does it simply show that they pursue their goals in opportunist ways?

On consider the RU position on choosing leadership in the Association. Local RU activists have argued that it’ is wrong for the Detroit Association to elect its Steering Committee, the Association’s policy-making body in between semi-annual membership meetings. (Steering Committee meetings are open to all; work committees are open to all; it is only the power of voting on policy matters that is limited to elected Steering Committee members.) RU forces have argued that the local Steering Committee should be composed of all “active” people who “volunteer” for it. They took up this position after RU candidates did very poorly in Steering Committee elections. However, on the regional and national level, where the RU has considerably more influence because of the voting structure of regional and national bodies, they argue for a centralized, elected leadership, who do not even have to be accountable to their home Association. The question must be asked: Why the glaring inconsistency? Why one set of criteria for local leadership and another set for regional and national leadership?

Yet another example of RU dishonesty in political principles came to light around the question of criteria for choosing delegates for activist trips. In the spring of 1975 the Detroit Association chose several delegates and alternates for a Midwest Activist Delegation to China. A selections committee, under the supervision of the Steering Committee, interviewed and ranked several possible participants on the basis of four criteria: a) Whether they had previously been to China; b) The level and nature of past Association activity; c) Commitment to future work with the Association; and d) The ability to politically represent the Detroit Association. (This last criteria was used to judge each person’s ability to accurately present and discuss the politics of the local Association, not whether or not one was with the majority or minority on particular issues, or what one’s personal political views were.) The selections committee gave low priorities to two individuals who work closely with the RU. This was on the basis of evaluations using all four, not just one, of the criteria. The RU’s response was to accuse the local Association, in an open letter to the region, with “discrimination” and a “violation of the Statement of Principles”. Now the RU was saying, as opposed to previous trips, that the only appropriate criteria that could be used for an activist trip was whether one had been “active”. Now they were opposed to evaluation of one’s past work. Now they said it was wrong to consider future commitment. Their sudden opposition to “political criteria” for representatives of the Association was a strange contrast to the previous year when they felt that their own type of “political criteria” justified a “security check” of a delegate by the RU itself. But perhaps the most revealing aspect of the RU’s response to the situation was their apparent blindness to the hypocrisy of their position. They denied that their own motivations were “political”. They denied that the reason they were upset over the evaluation of the selections committee was precisely because they wanted their political friends ranked higher. Thus they argued that the selections committee should not use “political criteria” precisely because they wanted to advance their political interests.

Other examples of the RU’s political dishonesty can be quickly cited:

* They contended, while at the 1974 national founding convention of USCPFA’s in Los Angeles, that the struggle in the Detroit Association was an antagonistic “two-line” struggle. In Los Angeles, they also contended, in a debate over candidates for the National Steering Committee, that they had majority support of the local Association. However, once back in Detroit and facing the membership at a meeting of the local Association, they dropped both characterizations.

* They have criticized others in the local Association for preparing for a membership meeting by ”getting together and talking before the meeting”. They characterized such discussion of political views prior to a membership meeting as “creating an anti-RU hysteria”. These are interesting criticisms from a group which itself caucuses and prepares politically for meetings of the Association.

* They have called local Association activists “careerists” and “seeking to be big frogs in a little pond” behind their backs, through rumor-mongering and gossip. They have never put forth any direct, principled criticisms which can be dealt with, evidently preferring to conduct political struggle through character assassination.

The consistency of the RU’s dishonesty and opportunism in their work in the Friendship Association raises serious questions. But some may ask: Shouldn’t such things be attributed to the individuals involved and not to organizational affiliations, such as the RU? Isn’t linking these things organizationally to the RU being anti-communist? To answer this, let’s look at what has happened in our Association.

A clear and general pattern over a period of time has emerged. Individuals associated with the Revolutionary Union have consistently engaged in dishonest, sectarian, and opportunist methods of work. The pattern has reached a point where it is clear from the frequency of incidents and from the similarity of incidents in other Associations across the country that there is an organizational connection and an organizational consistency. Thus it is appropriate, indeed necessary, to deal with the organizational roots if the problems are to be understood. To pretend there is no such connection is to be naive. The RU defines for itself, organizationally and politically, what are appropriate methods and style of work for its members in their broader activities. Fine. Our point here is that the RU has evidently tolerated (or even promoted) questionable methods of work on the part of its members, and our criticisms are aimed at those specific practices. We do not criticize the RU for functioning as an organization; rather, we criticize the RU’s failure, as an organization, to adopt honest and above-board methods of work.

The result of their failure to pursue their work in principled ways limits broad participation in the Association, narrows membership and outreach, and makes more difficult the Association’s task of uniting all who can be united on the basis of friendship with China.

An increasing number of Association activists, elsewhere as well as here in Detroit, have come to the conclusion that the Revolutionary Union is seeking control of the Friendship Association structure. It is questionable whether this is the result of a conscious decision on their part or whether it is simply the natural result of their style of work and their mistaken concept of “leadership”. But the question is actually irrelevant. Whether conscious or not, the effect upon the Association is the same. Of course, the RU denies either possibility and cries “anti-communism” every time it is raised.

But is it “anti-communist” to look at the reality of what is happening within the Association, particularly at the regional and national levels?

Is it “anti-communist” to assert – in opposition to the RU’s mistaken notions about “leadership” – that no one political group should be in a position to exercise control within the Association?

Is it “anti-communist” to believe the Association should be open, broad-based and independent in reality as well as in words?

And is it “anti-communist” to assert that if any one particular political group, regardless of who, effectively controls decision-making positions within the Association, then that Association is not, in reality, either open, broad-based, or independent?

These are legitimate questions. They are questions which involve important issues facing the Association, issues such as: Association leadership, internal democracy, membership structure and decision-making, finances and control of funds, accountability of leaders and leadership bodies, and local autonomy and the nature of regional and national structures. Let’s look at some of the current political struggles regarding these questions.

Control of the Association relates to how it is structured. The Detroit Association has always been an open membership group, with control resting ultimately in the membership. Interim decision-making and day-to-day leadership is the responsibility of an elected Steering Committee.

But not all Friendship Associations have an open membership structure. As difficult as it is to understand, in September 1974 at the founding convention of USCPFA’s, a national structure was formed for the Friendship Associations without any definition of whether there was a membership or not. For the past year local groups have followed a variety of practices, with many operating as self-selecting committees or with a self-selecting executive committee which made decisions and a membership or contributors list who had no voice or vote in Association policies. Thus, the issue of open membership was discussed at the Second National Convention in September 1974 and a tentative step was taken toward defining a standard association membership. At regional and national meetings the RU’s position has consistently been to oppose an open membership structure. Most recently they have argued for defining membership with one category of “active” members (undefined) who have a “voice” and “vote” in Association decision-making and another category of “paid” members who may only contribute money’ and attend Association events.

Questions must be asked: Why is the RU afraid of an open membership structure? Why are they reluctant to place decision-making in the hands of a broad membership? And if their approach were followed, who would define who is and who is not an “activist?” We believe an interesting fact to keep in mind when answering these questions is that the RU has steadily lost influence and control in Associations that have developed broad and open membership structures.

Association leadership – their selection and accountability – is another area related to control of the Association. In general, the RU has pushed for a type of regional and national leadership that discounts representation of the locals (according to them, making sure locals are represented is “mechanical” and “local particularism”). They state that leadership should be chosen solely on the basis of “proven ability to effectively lead friendship work”. (Quotes from “Build the Friendship Movement” by Hinton and Kissinger). While this may sound good, in practice their concept of “proven ability” has quickly boiled down to mean agreement with the RU. In fact, they have elected to regional and national bodies RU members who had no real base of local friendship work at the time of their election, RU members or RU supporters whose locals have floundered under their leadership, and RU members who were not supported by the majority of their local because of their mistakes in work at the local level. Where is “proven ability” in this type of leadership?

Another pertinent fact is that the RU opposes the current national by-law which requires candidates for the” National Steering Committee to have majority support of their local Association. (This by-law was passed by 1/3 of a vote at the 1974 founding convention. It passed over the opposition of RU forces.) Their opposition to this by-law is yet another example of their- disregard for local representation and local accountability in the regional and national structures.

While the RU’s concept of leadership in the Association .is, to say the least, laden with possibilities of elitism and sectarianism, neither is it consistent. At the regional and national levels, where they enjoy considerable influence due to the method of voting at those levels, they push for leadership to be carefully chosen on the basis of “proven ability” regardless of local support, local accountability, and local representation. However, in the Detroit Association, where the RU has faced a membership and drawn little support, they have thrown “proven ability” out the window. Instead, they argue that Detroit’s leadership (the Steering Committee) should be open to anyone who chooses to volunteer. The most likely reason for the inconsistency is perhaps too obvious: hegemony and control are more important to the RU than principle and democracy.

Voting at the regional and national levels of Association structures have been on the basis of “one Association, one vote”. This has meant that large membership Associations, some with hundreds of members, have had no more voice in determining policy or choosing leadership than small, self-selecting committees of less than 20. The reality is that many of the small Associations, often campus-based, have been unable to attract a broader participation in their Association, or they have not tried to do so. The result is that on the regional and national level the “one Association, one vote” approach has given the RU in¬fluence out of proportion to the actual views of total membership. Because of pressure from membership Associations, both large and small, the Second National Convention of Friendship Associations took a step toward a membership structure and proportional voting. However, the RU forces have consistently tried to sidetrack, bog-down, and water-down proposals for a membership structure and proportional voting at regional and national meetings.

Elections for the National Steering Committee from the Midwest Region, held in July 1975, provide an example of some highly questionable maneuvering by the RU. Prior to the July Regional meeting, the Regional Steering Committee (where the RU has considerable influence) sent information to all local Associations that nominations for the Regional representatives to the National Steering Committee would be made at the July conference, but that actual voting would take place either in the locals at a later date or at the National Convention in early September. This procedure was suggested because of the possibility of a new Southern region being established at the National Convention. This was the same procedure that the East Coast region was following. The July Midwest Regional Conference was a weekend meeting and the nomination of candidates was scheduled as the last item on the agenda, on Sunday afternoon. When that item came up, at 2:00 p.m. on Sunday, Clark Kissinger suddenly raised objections to holding nominations and said that the national by-laws required elections to be held right then. Several delegates raised objections, saying that, on the basis of the Regional Steering Committee’s mailing, they had come to the conference prepared for nominations, but not prepared for elections. Also, objections were raised because the question had not been raised earlier during the weekend. They should have been raised Friday night or on Saturday. A vote was taken whether to hold elections immediately or whether to continue with the procedure that had been previously announced. The RU-oriented Associations voted to hold elections immediately and the motion passed. The resulting election was a clean sweep for RU forces. Had the elections been held later, the same results are questionable, particularly in light of some RU-supported candidates being able to demonstrate that they had majority support of their local Association (a requirement to be a candidate). The ram-rodded election, and the bad taste it left in many mouths, was discussed at a Midwest caucus during the National Convention in late August. Despite a certain amount of breast-beating about ”sloppy” work, RU supporters never answered important questions which were put to them: Why hadn’t they raised the issue of the elections in the Regional Steering Committee and why at that time had they agreed with the proposal to hold nominations in July and elections later? Second, why had they not raised the question on the Friday or Saturday of the regional conference, when delegates would at least have had a little more time to deal with the question? Finally, why was it so important to hold the elections in July when at least one of the other two regions was following the same procedure initially announced by the Midwest Regional Steering Committee? These are still good questions, deserving of answers which are yet to be provided.

The RU’s drive for hegemony in the Associations can also be seen in other elections for regional and national bodies. In general, the RU has sought to gain as many positions as possible, without consideration of the stated goal of open, broad and independent Friendship Associations. When push came to shove, when things really mattered in terms of power and control in the Association, they showed no spirit of unity and no concept of working with others who did not agree with them. They sought and took everything they could get by any means, bureaucratic or political, principled or unprincipled. Of course, they deny doing this. But the votes, the pattern of voting, the tally, and the outcome speak for themselves. Our point here is not to claim the RU has control at the regional and national level. Rather, we are simply pointing to the fact that the RU sought control, they sought hegemony. We also know that the RU’s political position is that it is correct for them to seek “hegemony” in “mass” groups. Our criticism is precisely that it is politically incorrect for the RU (or any other group) to seek control or hegemony (which is not the same as providing leadership) within the Association. We base our criticism on the following argument: