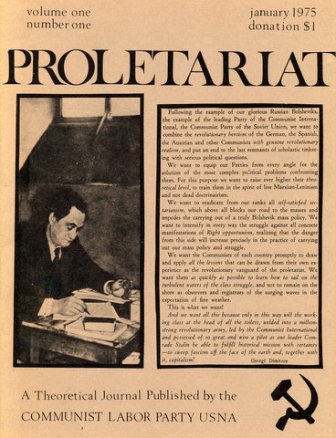

First Published: Proletariat, Vol. 1, No. 1, Janauary 1975.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

As a starting point, consider this quote from “On Contradiction” by Mao Tse-tung:

There are many contradictions in the process of development of a complex thing, and one of them is necessarily the principal contradiction whose existence and development determine or influence the existence and development of the other contradictions.

For instance, in capitalist society the two forces in contradiction, the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, form the principal contradiction. The other contradictions, such as those between the remnant feudal class and the bourgeoisie, between the peasant petty-bourgeoisie and the bourgeoisie, between the proletariat and the peasant petty-bourgeoisie, between the non-monopoly capitalists and the monopoly capitalists, between bourgeois democracy and bourgeois fascism, among the capitalist countries and between imperialism and the colonies, are all determines or influenced by this principal contradiction.

The contradiction we are dealing with, when we consider the question of fascism, is a secondary contradiction. It is a contradiction within the bourgeois aspect of the superstructure, just as the contradiction between monopoly and non-monopoly capitalism is a contradiction within the bourgeois aspect of the economic base. But within the economic base and within the political superstructure there is the contradiction between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. It is the overall relations between these classes which determine and influence the development of the contradiction between bourgeois democracy and fascism, as two aspects of the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. Thus we are dealing with two dialectically related forms of capitalist rule.

This elementary Marxist proposition is what the revisionists obscure about fascism. Instead of exposing the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, instead of showing how “democracy” is predicated on class oppression, the CPUSA has focused attention on these two forms of rule, as though they were two different kinds of social systems. In doing, this they have performed a valuable service to the bourgeoisie by fostering petty-bourgeois prejudices among the workers about the necessary tools of liberation, and possibility of destroying the bourgeois state and therewith both its forms. In dealing with this question the Marxist asks the question, “democracy for whom?” The masses in this country have never enjoyed real democracy; there has only been varying degrees of democracy for the bourgeois and petty-bourgeois classes. The rights which finally became extended in law to proletarians are usable, are allowed, only so long as they confine their attention to settling problems of capitalist rule. Even in the “best” of all possible bourgeois worlds, in very peaceful capitalism, still masses of people are necessarily locked out of the democratic process. It is not “democracy” but bourgeois democracy, and even when it works at its best, it effectively works not at all for millions of people on the bottom of society. In bourgeois society, under “democratic” conditions, the individual proletarian may have rights, but the proletariat-as-a-class can’t use the rights, unless they are to be used to reinforce the power of capital. That’s what bourgeois democracy means.

At the height of its popularity, the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie was extremely hidden, and at times even the majority of the people participated in strengthening its authority. During that period the masses acquire a certain faith in bourgeois democracy, a belief that the only possible kind of democracy is that which is granted to the people in law by the bourgeoisie. But that period is passing. The period of capitalism we are living in is the period of imperialist decay, the period of prolonged and general crisis, where the slightest movement among the people – the mere rustle of leaves – is cause for panic in the ruling class. This is a revolutionary epoch, and despite a lag in consciousness, the working class is beginning to shed its illusions about bourgeois democracy, while the bourgeoisie, despite tactical differences, moves towards discarding its own constitution and with it any pretense at democratic rule.

The history of bourgeois democracy is marked by backward and forward movement, from relative reliance on deception and bribery to relative reliance on force. But the ultimately permanent and unconditional aspect is open military dictatorship. While fascism is specific to imperialism and the general crisis of capitalism, after the epoch of the proletarian revolution has already begun, the preparation for fascism is inherent in the bourgeois dictatorship and has a long history of repeated practical execution. What causes the bourgeoisie to discard the constitution which yesterday they seemed to uphold? What causes them to adopt open terror and massive force? Why do they change from one form of rule to the other? Because they can no longer rule in the old way.

Why can they no longer rule in the old way? Because of an objective crisis, an economic and political crisis which is independent of anyone’s will. The crisis is the result of the development of the contradictions in the mode of production, in the economic base between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. The bourgeoisie tries one policy after another but the situation grows worse. Actually there is no policy which the bourgeoisie could implement to prevent the crisis. Nevertheless, the bourgeoisie is the ruling class and is therefore responsible for the crisis.

And how does the bourgeoisie get over these crises? On the one hand by enforced destruction of a mass of productive forces; on the other, by the conquest of new markets, and by the more thorough exploitation of the old ones. That is to say, by paving the way for more extensive and more destructive crises, and by diminishing the means whereby crises are prevented. (Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto)

When Marx and Engels wrote these words, the proletariat was just developing into an independent class, and was lucky to have even a few economic organizations to defend itself during a depression. In those times the bourgeoisie got out of the crisis just as Marx and Engels explained. The proletariat was unable to defend itself, and, being the main productive force, a portion of the class did not survive the crisis. Through starvation, disease, fatally hazardous occupations taken in desperation, and in general, through the lack of means to propagate the species, a small mass of the productive force – “labor-power” – ceased to be produced and reproduced, and another small mass was unable to survive. Moreover, another small portion of the proletariat was sacrificed, by the bourgeoisie in the conquest of new markets. At the same time, their ranks were replenished, at the end of the crisis, by a proletarianized section of petty-bourgeois who, having lost their meager means of production during the crisis, were economically compelled to offer their labor-power for sale in competition with the workers.

The overall political effect of the series of crises which capitalism has survived is that real economic and political power has been increasingly concentrated in fewer and fewer hands. Each crisis leaves the economic base of capitalism more centralized, more socialized, more concentrated. After a few such experiences, the proletariat began to wage organized economic and political struggles against the bourgeoisie. Armed struggles broke out. Yet the proletariat was still unprepared politically to actually seize power, and in consequence a part of the class did not survive the crisis.

During that very early period of capitalism, bourgeois democracy still represented a progressive political movement in part directed against the remnants of the feudal ruling classes (or, in our case, against the slave-owning aristocracy). But the rise of the bourgeoisie to power means also the creation of the grave-diggers of the bourgeoisie, the proletariat, and the ideological negation of capitalism – communism. While the proletariat always fought resolutely for the completion of the bourgeois democratic revolution, the bourgeoisie, observing the political potential of the proletariat, grows increasingly reluctant to carry though its own democratic movement. If the bourgeoisie had to call upon the workers to fight against aristocratic reaction, they immediately disarmed the workers after the job was done, and bolstered the state apparatus as an instrument of coercion over the rising proletarian movement. Having been defeated in the theoretical field, bourgeois ideology turned to deception, while politics came to be based on fraud, corruption and bribery.

The struggle to have democratic rights recognized in law is the bourgeois democratic struggle. The establishment of these rights in law is the completion of the bourgeois democratic revolution. The struggle by the proletariat to use these rights in their own, proletarian-class, interests, is not a continuation of the bourgeois democratic revolution; it is already the objective beginning of the proletarian socialist revolution.

All the contradictions of capitalism are intensified and magnified by the evolution of capitalism into its highest stage – imperialism. The domination of monopoly capital undermines the “free speech and assembly,” and mass electoral machinery. Imperialism subjugates whole nations and perpetuates absolutist rule. The form of rule in the colonies is generally open military dictatorship, denial of democratic rights for the oppressed nationality, occupation by the troops from the oppressor nation and political direction from the Capitol of the oppressor nation. The bourgeois democratic rights which continue to be extended to the citizens of the oppressor nation are all fraudulent, representing an aspect of reaction all along the line.

The imperialist bourgeoisie encourages “its own” proletariat to feel pride and comfort in the rights and privileges belonging to the members of an oppressor nation. It encourages political machinery for the purpose of involving the more active workers in the politics of the empire, in the corrupt reformism which endlessly negotiates for petty concessions, concessions which are not even aimed at alleviating the conditions of the whole class, but almost always for a small section of the class. And the imperialists have the money, derived-from the super-profits taken from the colonial peoples, to pay for such political movements. The political difference between the proletariat of the imperialist nation and the proletariat of the colonial nation, combined with the large-scale economic bribery of a section of workers in the imperialist nation, splits the working class into definite antagonistic political wings; one representing social-reformism and one representing revolution; one representing alliance with the imperialist bourgeoisie based on chauvinism and national privileges, and one representing alliance with the national liberation movement based on proletarian internationalism and the common struggle against imperialism.

The history of the USNA state illustrates this very clearly. For this imperialist state achieved its international position of power through the forcible suppression of the Negro people and other colonized peoples, through reactionary violence and the military occupation of colonial territory. And it did this with the help of the leading officials of the US labor movement, the bribed tools of reaction.

The imperialist bourgeoisie can continue bourgeois democracy only so long as it can back up this political base with material benefits. Otherwise it has no economic base in the population, not even with the millions of small producers, small capitalists, most of whom could not survive the compaction with monopoly capital. Thus the continuation of bourgeois democracy is contingent on the ability of the imperialists to provide a relatively sustained period of the expansion of capital, to keep super-profits flowing in; this is the only way they can build up a base of support among the petty-bourgeoisie and the upper stratum of the proletariat who have a toe or two in the petty-bourgeoisie. But the imperialists can only maintain their super-profits internationally in fierce competition with the other imperialist ruling classes. And ever since the proletarian revolution in Russia, the imperialists have to face the existence of territories where no capital can flow and no super-profits can be gained. The movement for national liberation poses the same threat, and the hegemony of the proletariat in that movement ensures that the territory will be, like the socialist countries, off-limits to the imperialists.

All this naturally intensifies inter-imperialist competition, and intensifies the contradiction between each imperialist ruling class and “its own” proletariat. The imperialist bourgeoisie is a class which depends for its very existence and the maintenance of its rule, on super-profits, and therefore on the maintenance of economic hegemony and control of the productive forces of other nations. In the end, it is dependent on aggression. Economic crisis in the era of imperialism cannot be separated from the imminent threat of world war.

Fascism is a product of the crisis. Fascism has already become the principal aspect of the imperialist bourgeois dictatorship. The periods in which bourgeois democracy prevails are no more than preparatory phases for an offensive against the proletariat. Slogans like “the state of the whole people” and phrases like “let’s heal the divisions and work together for our great nation” are ideological preparation for fascism. We can be sure that the imperialists’ appeal to “democracy” is but a prelude to the destruction of their own beloved constitution, just like we can be sure that bourgeois pacifism is but a prelude to new wars. The imperialists will have to go to war to protect the empire. But they will have to resort to extraordinary measures at home if they intend to send the workers into battle against a foreign nation. It has already been shown that the workers will not fight without serious and large-scale rebellion – that is what the experience of Vietnam proves. And that is why Stalin’s words, from 1928, are so relevant today: “It is impossible to wage war for imperialism unless the rear of imperialism is strengthened. It is impossible to strengthen the rear of imperialism without suppressing the workers. And that is what fascism is for.”

The crisis is well on the way. Economic observers have pointed out that it is the worst mess capitalism has gotten into since the thirties. The main brunt of the crisis has so far been shifted on to the backs of the other countries which are suffering much worse inflation than we are. And yet look how the inflation has generated political movement in the USNA! Just imagine what a 50% or 100% inflation rate is like!

Thus the point is inexorably reached where the bourgeoisie can no longer rely on deception and bribery. Not only can the bourgeoisie hot rule in the old way, but as a result of the economic chaos it has caused it has also generated in the masses, in the ruled classes, the inability to be ruled in the old way. The anarchy of production which turns into economic chaos is reflected in the political sphere by political anarchy, by spontaneous mass struggle which demonstrates incontestably that masses of people are willing, in fact eager, to discard old forms of rule and old constitutions because they will not live in the old way, will not survive by the old way and are ready to break through all constitutional barriers in order to get out of the crisis. In other words, bourgeois democracy becomes useless to both the decisive classes in society. It is in general what Lenin described as a “revolutionary situation.”

To the Marxist it is indisputable that a revolution is impossible without a revolutionary situation; furthermore, it is not every revolutionary situation which leads to revolution. What, generally speaking, are the symptoms of a revolutionary situation? We shall certainly not be mistaken if we indicate the following three major symptoms: (1) when it is impossible for the ruling classes to maintain their rule without any change; when there is a crisis, in one form or another, among the “upper classes,” a crisis in the policy of the ruling class, leading to a fissure through which the discontent and indignation of the oppressed classes burst forth. For a revolution to take place, it is usually insufficient for “the lower classes not to want” to live in the old way: it is also necessary that “the upper classes should be unable” to live in the old way; (2) when the suffering and want of the oppressed classes have grown more acute than usual; (3) when, as a consequence of the above causes, there is a considerable increase in the activity of the masses, who uncomplainingly allow themselves to be robbed in “peace time,” but, in turbulent times, are drawn both by all the circumstances of the crisis and by the “upper classes” themselves into independent historical action. Without these objective changes, which are independent of the will, not only of individual groups and parties but even of individual classes, a revolution, as a general rule, is impossible. (Lenin, The Collapse of the Second International, the same idea is expressed in Ch. 10 of “Left-Wing” Communism....)

It is of the utmost importance that we grasp Lenin’s definition very firmly. It means that, independent of anyone’s will or consciousness of the fact, there comes into being a change in the relation between ruling and ruled classes. It means that the objective relation between the ruling class and all the classes which it oppresses and especially the proletariat is one of acute class contradiction, is one in which these Glasses are resisting the ruling class either spontaneously or consciously. In fact, whether they are conscious of the consequences of their own practice, this practice has weakened the bourgeoisie, has made it impossible for the bourgeoisie to rule in the old way, in the bourgeois democratic way. As Stalin said, the victory of fascism

...Must be regarded not only as a symptom of the weakness of the working class and as a result of the betrayal of the working class by Social-Democracy, which paved the way for fascism; it must also be regarded as a symptom of the weakness of the bourgeoisie, as a symptom of the fact that the bourgeois is already is unable to rule by the old methods of parliamentarism and bourgeois democracy and, as a consequence, is compelled in its home policy to resort to terroristic methods of administration – it must be taken as a symptom of the fact that it is no longer able to find a way out of the present situation on the basis of a peaceful foreign policy, as a consequence of which it is compelled to resort to a policy of war. (Quoted by Dimitrov, in his Report to the 7th Congress of the Communist International)

The bourgeoisie has been weakened objectively by the class struggle of the proletariat. But the bourgeoisie enjoys a temporary tactical advantage, because the proletariat may not be conscious of the extent to which its practice has weakened the bourgeoisie. The party is responsible for bringing this consciousness to the proletariat. The party makes the class conscious of the fact that political struggle means the struggle between classes for state power and that state power means the effective command over an armed force. The party has to represent the most advanced consciousness of the class as a whole and make it aware that its movement has been preparing for years and generations to take state power and that it must carry this through to the end.

The bourgeoisie has also been preparing for years and generations, preparing its state apparatus and para-military formations to defend its rule by fire and sword. And the bourgeoisie is much more conscious of its own preparation than is the proletariat. Why is this? Because the bourgeoisie has long experience being on the strategic offensive whereas the proletariat is long accustomed to the strategic defensive. The bourgeoisie has long experience in developing and making use of the state apparatus in the class struggle, whereas the proletariat, having almost no such practical experience, has to be taught the theory of the dictatorship of the proletariat, and has to be taught about the practical experience of the dictatorship of the proletariat, from the Paris Commune to the underground Bolsheviks in the Soviet Union and the cultural revolution in China. If such knowledge can be imparted to ten thousand revolutionary workers, the problem of particular forms of struggle is already on the way to being solved.

What actually happens in a revolutionary situation depends entirely on the subjective factor in the proletariat.

it is not every revolutionary situation that gives rise to a revolution; revolution arises only out of a situation in which the above-mentioned objective changes are accompanied by a subjective change, namely, the ability of the revolutionary class to take revolutionary mass action strong enough to break (or dislocate) the old government, which never, not even in a period of crisis “falls”, if it is not toppled over.(Lenin, from The Collapse of the Second International, continued from the same passage)

The historical experience of the proletarian revolutionary movement shows that fascism is the result of the bourgeoisie launching civil war on its side, while the proletariat is prevented from waging the other side, the proletarian side, of the civil war, prevented from within its own ranks.

Imperialist war transforms opportunism, which had appeared as social-reformism, into social-chauvinism and an open alliance with the imperialist bourgeoisie. The revolutionary situation which developed during the first world war accelerated this identity into social-fascism. The policy of revisionism, of right-opportunism and its “left” off-shoots, is widely recognized as paving the way for fascism. How does it do this?

Revisionism does not recognize the principal contradiction in capitalist society as the contradiction between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat; it does not recognize that political struggle means the struggle between these two classes for state power, and it does not recognize therefore, that the aim of the struggle is the dictatorship of the proletariat. Revisionism understands imperialist society as having a progressive aspect which leads to socialism and a reactionary aspect which leads to fascism. Both of these aspects are seen as existing within the-bourgeois state, and the struggle centers around lining up the workers behind the “progressive” side of the bourgeoisie. The role assigned to the working class is that of an external condition on the bourgeoisie who constitute the internal basis of change. It is a conception of eternal struggle for better conditions under which to struggle for better conditions; it is a conception of eternal rule by the bourgeoisie and eternal struggle without victory by the proletariat. It is a conception of a never ending strategic defensive. In practice, revisionism relies on bourgeois democracy to defeat fascism. The revisionists fear fascism and cling desperately to bourgeois democracy.

Revisionism first appears as economism, as an attack on the conscious element. Its policy is the substitution of reformism for revolutionary Marxism. Its whole function is to draw off a section of the more advanced workers into the politics of the bourgeoisie, to channel the prejudices of the petty-bourgeoisie about “democracy in general” into the proletariat and create a petty-bourgeois democratic movement inside the proletariat, to create, in other words, an alliance between a section of the working class and the imperialist bourgeoisie against the oppressed masses of proletarians and against the oppressed nations as well.

The maturing of the economic crisis and the consequent revolutionary situation breaks down this unity; the revolutionary workers begin to break away from bourgeois-democratic prejudices and organize for the purpose of establishing the dictatorship of the proletariat. This development, which represents a leap from bourgeois to proletarian democracy, appears to the reformist politicians to be a provocation. It appears to them that the breakdown of bourgeois democracy can be prevented by this or that policy made by this or that party, just like the bourgeoisie believes that the crisis can be prevented by this or that policy made by this or that party. Revisionism has no use for any such concept as “objective relation between classes”. Revisionism does not recognize any situation which is objectively revolutionary. The breakdown of bourgeois democracy cannot be prevented by any policy of any party. What can be prevented is the breakdown of bourgeois democracy into fascism. But the only way it can be prevented is precisely by the revolutionary workers breaking away from bourgeois democratic prejudices and organizing for the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Revisionism therefore teaches the workers that the struggle is between democracy and fascism and not between the bourgeois dictatorship and the proletarian dictatorship. It teaches the workers that in this struggle between “democracy” and fascism, which determines everything in the world, including the victory or defeat of socialism, that in this struggle, the fascist aspect is is strengthened by communism, by the consciousness of Marxism-Leninism and conscious and purposeful revolutionary practice. The truth, as we can see from the fundamentals of Marxism-Leninism, and from the history of the proletarian class struggle, is that it is precisely the spontaneous struggle against the bourgeoisie which makes it more and more difficult for the bourgeoisie to rule in the old way; it is precisely the lack of consciousness of the new way which paves the way for fascism, and it is only the planned, conscious movement for the dictatorship of the proletariat which makes it impossible for the bourgeoisie to rule in any way.

The revisionist CPUSA has been spreading reformism for a long time undisturbed by a Marxist-Leninist party which is only now just been born. The absence of a revolutionary Marxist critique left room for a “left” adventurist line which exercises some influence among the revolutionaries. The most advanced expression of this “left” line is George Jackson’s analysis of fascism, (see Blood in my Eye) Taking the CPUSA as representative of Marxism on the subject, Jackson came to the conclusion that we have always lived under fascism. Hidden in Jackson’s criticism of the CPUSA is the revolutionary attitude of the proletariat which understands that democracy granted in law by the bourgeoisie is no more than a facade for the dictatorship of that class. However, reformism cannot be defeated by anarchism. Anarchism obscures the distinction between bourgeois democracy and fascism and also has no use for the concept “objective revolutionary situation”. The reformist believes that there is never a revolutionary situation until after the fact, until after it is proven that the masses were subjectively prepared. The anarchist believes that there is always a revolutionary situation, beginning with the recognition of the class nature of the state in the subjective consciousness of the vanguard.

The “left” error also gives the revisionists a golden opportunity to distort Dimitrov’s definition in a liberal way. It is asked, if Dimitrov referred to the most chauvinist, most reactionary, most imperialist, then doesn’t that mean that there must also be a least chauvinist, reactionary, imperialist, side of the bourgeoisie? Yes that is indeed what it means. However, that is no wonder.

The wonder is that communists, who understand the world through the philosophy of dialectical materialism, should wonder at such a proposition. Doesn’t everything divide in two? Why can’t the bourgeoisie divide in two? In fact, the unity of the opposites within the bourgeoisie is strictly temporary, relative, and conditional. It is impossible, in the final analysis, for the bourgeoisie to form a monolithic political body, since there is nothing they can do, no policy they can implement, which can save their rule. For the proletariat the situation is just, the opposite. It is possible for the proletariat to create a monolithic political body because the proletariat can make a concrete analysis of concrete conditions, and for it there is such a thing as a correct political line manifested in a definite, and definitely correct policy which can turn into a material force and change the world. That’s one of the differences between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

Dimitrov’s definition refers to these as part of the rule of finance capital, i.e., both aspects belong to, are characteristic of, that class. Thus, the opposite of “most chauvinist” is not “internationalist”; the opposite of “most reactionary” is not “progressive”; the opposite of “most imperialist” is not “socialist”. That distortion, which is not at all inherent in Dimitrov’s definition, is precisely the revisionists’ liberal-reformist conception of the state. So that, while we understand the differences, the contradictions, the opposing political alignments within the bourgeoisie, we also understand the unity, that they are all within the bourgeoisie, all expressions of the rule of that class. We recognize that in relation to the state one aspect or the other must be principal and that determines the particular form of rule at any particular time. The particular form of rule of one imperialist state may be in contradiction to the form of rule of another imperialist state; for example, the bourgeois democratic states were in contradiction to, and eventually antagonistic contradiction to, the fascist states in the 1930s-40s. Nevertheless, the bourgeois democratic states and the fascist states together formed a unity in opposition to socialism; thus, even while the bourgeois democracies fought against fascism and helped the Soviet Union, they constantly conspired with the fascist governments to weaken and overthrow the dictatorship of the proletariat.

It is clear that an attack by the bourgeoisie generates widespread resistance. The proletariat must defend itself against the attack; it has to defend its living standards, its political rights, its economic and political organizations, etc. Certainly the revisionists will try to lead a movement to resist fascism, in the form of an anti-fascist, anti-monopoly coalition. The aim of this revisionist led movement is to restore the old class harmony which was the basis for the continuation of bourgeois democracy. This reflects the interests of a substantial base in the population, a base which is disintegrating, it is true, but whose political consciousness always lags behind its new conditions. The politics reflecting the petty-bourgeoisie and the upper stratum of the proletariat is to fight against the effects of capitalism on themselves while fighting to maintain the capitalist system as a whole. Under attack by the fascist elements of the bourgeoisie, millions of small producers, skilled workers and intellectuals will fight against fascism to defend their old status in bourgeois society. Even some of the liberal bourgeois may be willing to resist transgression of the constitution.

Thus there is a temporary basis of unity existing under the umbrella of resistance. The CPUSA says flatly in a recent editorial in the People’s World that resistance is the only weapon we have. The CPUSA is already preparing the ideological ground for the hegemony of the liberal bourgeoisie in their “defense” of the proletariat. The conciliators of revisionism are helping to prepare this defeat by spreading the illusion that imperialism is collapsing and can be pushed over without a revolutionary offensive. The “left” opportunists will insist that the proletariat should have nothing to do with the resistance movement and will conduct premature armed struggle, thus guaranteeing revisionist domination of the movement.

The problem of communism is how to unite the working class in a movement to defend the bourgeois democratic revolution and the rights gained from it, and transform this movement into an offensive, into the proletarian socialist revolution. The movement to resist fascism appears as a continuation of the strategic defensive. In fact it is actually a tactical defensive in the context of a new stage of strategic offensive. Only revolutionary Marxism can make this clear. Revisionism stands opposed to Marxism; it strives to contain the struggle and keep it within the confines of strategic defensive. The party of the proletariat must prepare the whole class and all the oppressed people for a second attack even if the defense is successful. The lesson we learn from history is that a strong communist party leading the mass movement of resistance to fascism may successfully beat back fascism; but if such a movement does not understand that in order to defend itself it must pass over to the offensive, then fascism won’t be defeated, only temporarily delayed. Only when the proletariat learns, and the oppressed masses can see by their own experience, that only proletarian revolution actually defeats fascism, will the defeat of fascism be certain.

It is necessary to repeat: the subjective factor is the only factor we have control over. The extent to which the proletariat is united behind its Marxist-Leninist party is the extent to which the bourgeoisie will be split and its forces in disarray. The main weapon in the hands of the bourgeoisie is the confusion, the lack of consciousness, the influence of opportunism, in the proletariat. We can see the elements of a revolutionary situation coming into being right now. We can see that a world economic crisis is already under way. We can see that an imperialist war is an imminent threat to the exploited and oppressed people everywhere. A few months ago comrade N.P. spoke in San Francisco and touched on this subject. He said that fascism represents a danger and an opportunity and that we should not be afraid to take the initiative. He emphasized, in that speech, the decisive role of ideas, of the ability of the revolutionary people to think, to plan, to understand and deal with objective reality. To see only the danger is a right error. To see only the opportunity is a “left” error. And the worst error of all is to underestimate the role of consciousness. Our task is to educate the proletariat in the science of Marxism-Leninism, to establish a revolutionary communist presence in the class which can become the vanguard of the oppressed and exploited workers. Only with such a force in the working class can we unite the class, break the influence of opportunism, and build a united front against fascism which can go over to the offensive and defeat fascism once and for all. Everyone must understand that a whole lot depends on what we do.

(Based on, and edited slightly from, a speech given on behalf of the S.F. Continuations Committee, August 10, 1974)