First Published: Proletariat, Vol. 1, No. 1, Janauary 1975.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

On September 12, 1971, a Trident jet carrying Lin Piao crash landed 160 miles into the Mongolian frontier. The career of one of the world’s foremost “Maoists” ended in flames. Only months later did the world find out for sure where in fact Lin Piao’s real allegiances lay. For those who had substituted empty phrase-mongering for Marxism-Leninism, for those who had done no more than memorize selected passages from the Redbook, the revelation of Lin Piao’s plot on Mao Tse-tung’s life was a cruel slap in the face. But for those Marxists who were acquainted with the history of the communist movement and its leaders, there was always something fishy about Lin Piao’s sanctification of Mao Tse-tung. Obviously something more was at work here than naive “hero” worship. This was an attempt to separate the Chinese revolution from the October Socialist Revolution, to separate Mao Tse-tung from Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin, to isolate him. But was Lin Piao after Mao alone, was this just a “power struggle” between “personalities,” as the bourgeois press so often characterizes it? No. Lin Piao was part of a plan to overthrow the socialist state, and following that, the socialist relations of production in China. One thing stood in Lin Piao’s way – the Marxist-Leninists in the Communist Party of China, led by Mao Tse-tung. That is why Lin Piao applied traditional guerrilla tactics against Mao Tse-tung: isolate and destroy.

We are not so concerned about the second part of this process, namely the plot itself. The details have been well-publicized in numerous magazines and newspapers. Besides, the plot failed; Lin Piao is certainly dead. But the bourgeois class which Lin Piao represented is far from dead. And so the attempt to isolate Mao Tse-tung goes on. It is the analysis of Lin Piao’s methods of isolation that is vitally important to not only the Chinese Communists, who have devoted dozens of pages in their publications to it, but also in fact to the international communist movement. For as we have seen time and time again in this country, an incorrect estimation of the Chinese Revolution goes hand in hand with opportunism. Later on we will look at why this is so.

The attempt to isolate Mao Tse-tung has gone on for nearly fifty years. Its roots today lie not only in China, but particularly in the change which occurred in the international situation following Stalin’s death in the Soviet Union. Until then the socialist camp represented a vast expanse of land and peoples from Vietnam to East Germany. The bourgeoisie well understood the need to break up that unity. They had already suffered a decisive defeat with the Moscow purge trials in the latter half of the 1930s. But then war was approaching; the kulaks had been smashed; large-scale industry in the Soviet Union was growing rapidly; in short, the economic basis of the Soviet Union was quickly being transformed into a socialist one.

After the war, conditions were somewhat different. A large part of Soviet Industry had been destroyed. Tens of millions of people had died, including hundreds of thousands of steeled Bolshevik cadre, the Soviet economy had to be rebuilt for the second time in thirty years. It was during this period of economic dislocation that the bourgeoisie began making their moves. The culmination of this treachery was the coup d’etat by Khrushchov and his forces. The Soviet state had been seized by the Russian bourgeoisie, the same class that formed the Fifth Column in the thirties, the same class that capitalized off the petty profiteering immediately following the seizure of state power by the Bolsheviks in 1917. With this seizure of state power by the Russian bourgeoisie, the Soviet Union left the socialist camp. In order for a state to have a socialist character, it must be a dictatorship of the proletariat. The Soviet state under Khrushchov could not longer be called a socialist one precisely because it was no longer an instrument of proletarian dictatorship but rather an instrument of bourgeois dictatorship.

Some immense problems immediately confronted the Russian bourgeoisie. Domestically, how to separate the Soviet working class from the means of production. Internationally, what to do with the socialist camp, particularly China. This latter question is for the Russian bourgeoisie not just an ideological one; it is a military one, a question of war. War, as we know, is simply politics by other means. And what is the political problem here? Because of the tremendous revolutionary history of the Soviet peoples, the Russian bourgeoisie was forced to don Marxist clothing. In doing that, however, they came face to face with the real Marxists of the socialist camp, especially the Albanian Party of Labor and the Communist Party of China. The struggle was on. Either the Russian bourgeoisie would be exposed as phony Marxists and traitors to the working class or they would succeed in isolating the communists in the socialist camp. This attack had to start with China, mainly because of the common revolutionary bonds between the Chinese and Soviet peoples and because of the enormous international significance of the Chinese revolution. Furthermore, an attack on China had to begin with an attack on its leadership, an attack on Mao Tse-tung. This right wing attack took the form of outright slander and lies.

Now we can see the connection. The attack from the right from the USSR bourgeoisie had its complement in China. All but the most hardened philistines now realize that there is still a bourgeois class within China, a class that had been deprived of political power, but one which will attempt to seize political power back. The Chinese bourgeoisie, like the Russian, wants to eliminate the Marxist-Leninist forces led by Mao Tse-tung. This the basis of unity between the two bourgeoisies. But the Chinese bourgeoisie, for whom Lin Piao was a major spokesman within the Communist Party of China, could not attack Mao in the same way that the Russian bourgeoisie could. They would be immediately exposed and discredited, as they were in the Cultural Revolution. This defeat led to a change in tactics, that is, an attack from the “left,” but with exactly the same purpose in mind: the restoration of capitalism in China. This is the essence of Lin Piao’s politics. Is it any wonder that this plane was heading towards the Soviet Union? Or is it any wonder that the Soviet journal Isvestia acknowledged that Lin Piao backed rapprochment between the Soviet Union and China?

In this context, it is clear that a correct appraisal of the Chinese Revolution and the contributions of Mao Tse-tung to the world communist movement is not just an abstract theoretical exercise, but a question of immediate importance. Without such a correct appraisal, we cannot possibly struggle in the best way against the capitalist bandits who have stolen state power in the Soviet Union. It. is also no accident that it is the influence of this very same Lin Piao that has prevented many groups around the world from really participating in this struggle. In fact, while pretending to fight the Soviet capitalists, some of these groupings have only given them more ammunition because of their blind and philistine understanding of the Chinese revolution.

This is the significance for us of the exposure of Lin Piao. It is not a question of China’s internal politics. It is a question of proletarian internationalism, of coming to the aid of our class not only in the Soviet Union and China but also in the USNA. China is a beacon of socialism around the world. Our own proletariat must learn from the experience of the Chinese revolution. But they cannot do this properly so long as the opportunist appraisal of this revolution goes unexposed.

Many communists long ago became suspicious of Lin Piao’s constant characterization of Mao Tse-tung as the greatest genius of all time. What was not so clear was that this was part of an overall ideological plan of attack that was started years before. In fact, Lin Piao could not isolate Mao Tse-tung without isolating the Chinese Revolution as a whole. In 1967 he wrote:

The victory of the Chinese people’s revolutionary war breached the imperialist front in the East, wrought a great change in the world balance of forces, and accelerated the revolutionary movement among the people of all countries. From then on, the national liberation movement in Asia, Africa and Latin America entered a new historical period.[1]

And what is this “new historical period?”

...Leninism is Marxism in the era of imperialism and proletarian revolution. The salvoes of the October Revolution brought Leninism to all countries, so that the world took on an entirely new look. In the last fifty years, following the road of the October Revolution under the banner of Marxism-Leninism, the proletariat and the revolutionary people of the world have carried world history forward to another entirely new era, the era in which imperialism is headed for total collapse and socialism is advancing to world-wide victory.[2]

Before we go on to analyze why the need for this “new era,” let’s take a look at its validity. It is clear that this formulation has been accepted by many a force on the left, especially in the USNA. Following on the heels of Lin Piao, these groups seek to learn nothing from the October Revolution. After all, that was in “another era.”

What is the importance of Lenin’s analysis that we are living in the era of imperialism and proletarian revolution? First of all, the world “era” has a specific meaning for Marxists. “An era is called an era precisely because it encompasses the sum total of variegated phenomena and wars, typical and untypical, big and small, some peculiar to advanced countries, others to backward countries.”[3] In this same essay Lenin makes the distinction between the era in which Marx and Engels lived and the era in which we are living now. As Stalin put it:

Leninism is Marxism of the era of imperialism and of the proletarian revolution. To be more exact, Leninism is the theory and tactics of the proletarian revolution in general, the theory and tactics of the dictatorship of the proletariat in particular. Marx and Engels pursued their activities in the pre-revolutionary period (we have the proletarian revolution in mind), when developed imperialism did not yet exist, in the period of the proletarian preparation for revolution, in the period when the proletarian revolution was not yet a direct, practical inevitability. Lenin, however, the disciple of Marx and Engels, pursued his activities in the period of developed imperialism, in the period of the unfolding proletarian revolution, when the proletarian revolution had already triumphed in one country, had smashed bourgeois democracy, and had ushered in the era of proletarian democracy, the era of the Soviets.[4]

This era is not just a question of imperialism, for capitalist imperialism existed in Europe and the USNA some twenty years before the October Revolution. Yet this era did not really begin until 1917. In fact, as The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolshevik) states, “The October Socialist Revolution thereby ushered in a new era in the history of mankind – the era of proletarian revolution.”[5] If we return to Lenin’s definition of what an era is, we can see that imperialism by itself could not change the basic pattern of the class struggle. But imperialism plus the October Revolution could and did change that pattern.

Now the world as a whole was not simply divided up into oppressor and oppressed countries, as had been the case before. Now two hostile camps stood opposed to each other – the camp of socialism and the camp of capitalism. The bourgeois class around the world saw the threat (to them) of communism in proportions they had never before even contemplated. Proof enough of this was the fact that as many as fourteen different nations saw fit to attack the Soviet Union almost immediately after the proletariat had seized power.

The October Revolution changed the nature of the colonial revolutions as well. Previously, the national bourgeoisie of the colonies could play a leading role in the struggle for emancipation. The hegemony of the proletariat in the colonial revolution was regarded as unnecessary at best and a positive hindrance at worst. But the October Revolution put an end to all such bourgeois nationalism. The national bourgeoisie of the colonies had up until 1917 been playing an increasingly conciliatory role towards the imperialists. As history marched onward, as the world became fully divided up amongst the imperialist powers, the colonial bourgeoisie more and more proved its inability to lead the struggle for national liberation. A qualitative leap was taking place, and the October Revolution was the nodal line. Before then the question of the colonies was either ignored or placed in the category of bourgeois revolution. It is only after the October Revolution that we can say, as Stalin, that “the era of revolutions for emancipation in the colonies and dependent countries, the era of the awakening of the proletariat of these countries, the era of its hegemony in the revolution, has begun.”[6]

Finally, the October Revolution ushered in a general worldwide crisis for capitalism. The essence of the First World War was the redivision of the world for imperialism plunder. But with the advent of the October Revolution, fully one sixth of the world was taken away from the capitalists. This is what precipitated the general world crisis of capitalism. Capitalism still suffers from cyclical crises every few years. But after 1917, the capitalist world was in a permanent, general state of crisis from which they have not managed to emerge to this day.

The Chinese Revolution is a continuation of the October Socialist Revolution. In his work On New Democracy, Mao Tse-tung pointed out that there were two basic periods in the history of the Chinese Revolution: the bourgeois-democratic, led by the bourgeoisie, and the proletarian, led by the proletariat in alliance with the peasantry and other revolutionary elements of the petty-bourgeoisie. And what was the historical turning point? The First World War and the October Revolution. From this time on, the Chinese democratic revolution ceased to be a part of the old type of bourgeois revolution and became a part of the proletarian socialist world revolution. In this way Mao Tse-tung clearly establishes the line of continuation between the October Revolution and the Chinese Revolution.

Thus the latter did not initiate any new era at all. Rather, it was a striking illustration of the fact that the former had indeed initiated a new era of imperialism and proletarian revolution. The Chinese revolution proved that the question of emancipation of the colonies was no longer a “separate” question but, on the contrary, a question for the entire world revolutionary movement to deal with.

Lin Piao “invented” a new era in order to break this line of continuity. In order to attack something, it is always better to isolate it from everything in its environment which gives it strength. Hence in order to attack the Chinese Revolution, it must be separated from the October Revolution. This is done by Lin Piao in a very clever way, and from the “left,” as it were. The Chinese people and other revolutionary peoples around the world are given a “pat on the back.” Even though these people have followed the course already outlined by Marx and Lenin, they are told they have brought about an entirely new state of affairs, a new era. Of course, how this “new era” is concretely different from the era Lenin described cannot be spelled out, for then it could be only too clear that Lin Piao had indeed invented something out of his head. But the motive is clear enough: there was no longer a need to learn from Lenin and Marx. We are in a “new era” now. All we need to study is the “Red Book.” Isn’t this the line that became so prevalent in the USNA “Left?”

But this is not all. The phrasing Lin Piao used constitutes an “improvement” on Lenin. It presents a seemingly brighter picture: the era when imperialism is heading for total collapse and socialism is heading for worldwide victory. Isn’t this much more descriptive than Lenin’s drab “imperialism and proletarian revolution?” Certainly it presents a much more “optimistic” picture. But it is precisely such optimism that we should be wary of. In the long run it is true that imperialism will “collapse.” The reason it will collapse, though, is because the proletariat led by its vanguard party will consciously destroy it. To say simply that imperialism will collapse conveys the impression that it will fall over from its own weight, that the conscious element is unnecessary. This is the same impression CPUSA chief Gus Hall gives in his pamphlet “The House of Imperialism is Crumbling.” The idea that imperialism will collapse or crumble without being destroyed by the proletariat led by a conscious Marxist-Leninist Party contradicts the essence of Marxist theory and strategy. Marx always taught that without class-consciousness, without the recognition of the necessity of the dictatorship of the proletariat, the working class would never destroy capitalism.

The second part of the formula also needs scrutinizing. Is socialism marching to worldwide victory? In the long range sense, of course it is. This is inevitable since socialism is the next step forward historically from capitalism and feudalism. But over the last two decades, who can deny that there have been some serious setbacks for the cause of socialism? The Russian bourgeoisie has seized control of part of the Soviet state apparatus, and this had happened as well in Poland, East Germany, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Rumania, Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia. Revisionist communist parties dominate the political scene throughout Europe, the USNA, and South America. We are not disheartened at this situation, only more determined to expose these phony parties so that they will spread a minimum of confusion. But neither do we need fancy phrases to hide the real state of affairs in the world today. This is why Lenin’s formulation is the correct one. Lenin never spoke of imperialism meekly surrendering. No, he showed how imperialism was “reaction down the line” and that this epoch would be one of extremely fierce class struggle. In sharp contrast to Lin Piao’s smooth evolution to socialism, here is Lenin’s sober estimate of the real situation: “World history is leading unswervingly towards the dictatorship of the proletariat, but it is doing so by paths that are anything but smooth, simple and straight.”[7]

Lin Piao was in direct opposition to this. As a representative of the Chinese bourgeoisie it was to his advantage to lull the workers to sleep. And it is in his formulation that we see yet another tie between him and the Soviet revisionists. They too claim that everything is fine within the socialist camp, while they prepare for military intervention in China. They too claim that imperialism will collapse, while they themselves strive to secure new colonies for exploitation. This line is one that is held by virtually every revisionist party in the world, including the CPUSA and large sections of the USNA “left.” The essence of this line, however, is something entirely different than what it seemingly expresses. The essence of this line is to protect the bourgeoisie which has seized state power in the Soviet Union, and this is exactly what Lin Piao was doing.

The idea of imperialism crumbling of its own accord and socialism marching to an easy victory provides an ideological basis for the revisionists’ glorification of “detente,” otherwise known as imperialist peace. But what Lenin understood by imperialist peace, namely, a lull in between imperialist wars, a period in which the imperialists are preparing for a new division of the world – is quite different than that of the revisionists. Lenin proved that imperialism made wars for new markets inevitable. Thus the war in Vietnam, the Middle East, etc, are “normal” insofar as imperialism cannot exist without such wars. According to revisionist chief Brezhnev, however, perpetual peace – or “detente” – is the normal state of affairs for imperialism. He made this clear in his speech to the electorate this May. First he spoke of Vietnam, the Middle East and the “cold war” and the generally tense relations that existed between the socialist and imperialist camps. One would think that since socialism and imperialism are irreconcilable, relations naturally would be tense between the two camps. But not according to Brezhnev:

Our Party never considered such a situation inevitable, much less normal. Having assessed the general balance of world forces, we arrived at the conclusion several years ago that there existed a realistic possibility of bringing about a radical change in the international situation. It was a matter of starting a broad constructive discussion and the settlement of the issues which had piled up. These intentions and this policy of our Party found their general expression in the Peace Program proclaimed by the 24th CPSU Congress.[8]

Here we should note that both Lin Piao and the revisionists agree on the fact that a new era had begun, different from the one Stalin defined fifty years ago. CPUSA chieftan Gus Hall put forward this idea in his latest book on imperialism:

One of the basic conclusions we draw from the new epoch concept is the fact that world wars are not now inevitable. In the epoch when imperialism was the dominant force, wars of conquest between imperialist powers for the redivision of the loot were inevitable. The shift in the world balance of forces has made a shift in the outlook for peace not only possible but crucial for mankind’s survival.[9]

Lin Piao’s formulations of the “new era” come from the “left” because his aim was to separate the Chinese Revolution from the October revolution in order to pave the way for capitalist restoration in China. Leonid Brezhnev’s and Gus Hall’s formulations on this point come from the “right” because they must separate the Soviet working class not only from the means of production but also from their revolutionary heritage, in order to restore capitalism in the Soviet Union. But in both cases, what is involved is a clear denial of Marxism-Leninism.

It is no accident that the Chinese Communists struck a telling blow at this deviation at their Tenth National Congress. Chou En-lai’s report carried a clear, refutation of Lin Piao and his followers:

Lenin “therefore concluded that ’imperialism is the eve of the socialist revolution of the proletariat,’ and put forward the theories and tactics of the proletarian revolution In the era of imperialism. Stalin said, ”Leninism is Marxism in the era of imperialism and the proletarian revolution.’ This is entirely correct. Since Lenin’s, death, the world situation has undergone great changes, but the era has not changed. The fundamental principles of Leninism are not outdated; they remain the theoretical basis guiding our thinking today.”[10]

Lin Piao’s scheme unfolds from this invention of the “new era.” Though he was never a Marxist (in all his writings up until 1960, there are only two references to Marxism-Leninism), he knew enough about Marxism to realize why Marx and Lenin’s teachings in particular form the basis of modern revolutionary doctrine. Of the era of bourgeois-democratic revolution, which lasted until World War One and the October Revolution, Marx was without a doubt the principal spokesman. Of the era of imperialism and socialist, proletarian revolution, which we are still in today, Lenin was the principal spokesman. This is basically why the doctrine which represents all the goals of the modern revolutionary movement is termed “Marxism-Leninism.” And it will continue to be termed thus until society enters a new historical era. This is why we reject such formulations as Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism, or Marxism-Leninism-Maoism.

Stalin, Mao Tse-tung, Enver Hoxha and other communist leaders have rejected the many attempts to place them on the same level as Marx and Lenin as far as their contributions to the theory and principles of the Communist movement. Not because they were any lesser men. Rather because they viewed themselves as the faithful disciples of Marx and Lenin instead of as “inventors” who were going to raise Marxism-Leninism to a higher stage. Stalin, Mao Tse-tung and Enver Hoxha are continuers of Marxism-Leninism. They proved that Marxism-Leninism was not a local or a national doctrine, but in fact an international doctrine, one that was applicable to all countries at all times in the present era.

Yet there have been repeated attempts to separate these leaders from Marxism-Leninism. This is done somewhat “cleverly” through flattery, telling them that they are the greatest geniuses of all time, that they have raised Marxism to an entirely new level. Is it any coincidence that the factionalists of the old CPUSA, Foster and Bittelman, competed with each other to see who could prove himself to be the best “Stalinite?” With Marxist clarity, Stalin crushed the attempts to set him up on a pedestal to make a better target of him. “Foster and Bittelman see nothing reprehensible in declaring themselves ’Stalinites’ and thereby demonstrating their loyalty to the CPSU. But, my dear comrades, that is disgraceful. Do you not know that there are no ’Stalinites?’”[11] The “cult of the individual” had nothing to do with Stalin, except insofar as he consistently opposed it. Really it was the enemies of the CPSU such as Foster and Bittelman who pushed the cult of the individual, who proclaimed their loyalty to “Stalinism.” As for Stalin, he made his position quite clear: “I am only a disciple of Lenin, and my whole ambition is to be a faithful disciple.”[12]

Stalin and Mao both made it clear that in being disciples of Marx and Lenin, they were in the highest way fulfilling their duties as communists. These two great leaders always repudiated attempts to invent something new and wonderful, which did not correspond to the real world, such as a “new era.” The historical examples they have set show that those who strive to be leaders by inventing new “isms” and proclaiming themselves as ultimate geniuses are not more than opportunists. Leonid Brezhnev and Gus Hall are prime examples of this. No, the real leaders of the proletariat, such as Stalin and Mao Tse-tung have distinguished themselves by their application of Marxism-Leninism to the concrete conditions in their countries. In so doing, they have carried out the tasks of this historical era of imperialism and proletarian revolution.

Lin Piao used the very same tactics as Foster and Bittelman, only with more skill and international effect than his predecessors. In fact, close to a billion people, almost one third of the entire world, were exposed to Lin Piao’s hero worship of Mao Tse-tung. We refer of course to the famous Red Book which carried Lin Piao’s instructions: “Comrade Mao Tse-tung is the greatest Marxist-Leninist of our era. He has inherited, defended and developed Marxism-Leninism with genius, creatively and comprehensively, and has brought it to a higher and completely new stage.”[13]

This formulation appears time and time again in Lin Piao’s writings. It practically became his trademark. He had hit upon an explosive idea. All over the world, so-called revolutionaries who hadn’t read any Marx or Lenin anyway now found so-called “theoretical” justification for their ignorance, and from a leading member of the Communist Party of China, no less! Marxism-Leninism became old hat, “outdated,” while “Mao Tsetung Thought” was raised to the level of an “ism” for a brand new “era.” With the shortsightedness that characterizes all amateurs, these naive revolutionaries pinned on their Mao badges, stuffed the “Red book”, in their back pocket, memorized a few quotations (after all, hadn’t Lin Piao also told us that the best way to learn Mao was to memorize a few key passages?), and proclaimed themselves the vanguard of the proletariat. Little did these people know that they had fallen into a carefully conceived trap, a trap that assumed international dimensions. Let us examine the dialectics of this trap more carefully.

First, Lin Piao did not carry out his plan alone. He had to prepare as many people as possible ideologically. The immediate problem was this. Mao Tse-tung has always considered himself a continuer of Marxism-Leninism, and this point is made often enough in his writings. Now, how to make everyone read Mao Tse-tung and yet miss this essential point? The solution came with the problem. Urge a method of study which tends to produce philistines and not rounded Marxist-Leninists: “In order really to master Mao Tse-tung’s Thought, it is essential to study many of Chairman Mao’s basic concepts over and over again, and it is best to memorize important statements and study and apply them repeatedly.”[14] This seems like an easy and palatable way to master Marxism-Leninism. Too easy. The mastery of Marxism-Leninism is an uphill struggle, one that demands conceptual understanding. But of course Lin liao greatly feared just such a conceptual understanding. He needed the freedom to move that came with people’s mistaken belief that he was a faithful Marxist. He needed the “freedom” to put forth his own “theories” on the

Chinese revolution, theories that would pave the way for the seizure of state power by the Chinese bourgeoisie.

Let this be a good lesson to us. We communists must carefully scrutinize every communist leader and every communist party from the point of view of Marxism-Leninism. Those parties and leaders which are truly Marxist-Leninist will demand such scrutiny, while those who are not fear it. Marx long ago warned that we cannot afford to base our opinion of an individual on what he things of himself, but only on what that individual represents objectively, and this applies to parties as well. We support Marxist-Leninists and parties which uphold Marxism-Leninism always and everywhere; but we are fools if we support individuals and parties simply because they attach the name communist or socialist to themselves.

Chronologically, the first step in Lin Piao’s “theory” was the idea of a “new era” and the separation of Mao Tse-tung from the historical continuity of Marxism-Leninism. Though the philosophical basis of Lin’s theory in general is idealism, the concrete manifestations are these two concepts. They are the most obvious deviations, and form the keystone of the rest of his “theory.” It would be wrong, however, to stop with the surface phenomena. For in fact it is really some of his other deviations that have the most profound impact on the international communist movement. I refer particularly to his assessment of the Chinese Proletarian, Cultural Revolution and the attempts to restore capitalism in the USSR and in China, the national and colonial questions, and the role of ideological struggle in the proletarian movement. Clarity on these points is hardly an abstract endeavor at this particular time. No, we could go so far as to say that without this clarity, we will be unable to move forward. This hardly means that Lin Piao is some sort of evil genius because he has succeeded in confusing certain sections of the communist movement. On the contrary, he represents a bourgeois deviation in the movement; his writing constitute a summation of .that deviation; and therefore in refuting him, it becomes clearer and clearer that he is only a secondary target. Our primary aim is the exposure and expulsion of this deviation from the communist movement.

Restoration of capitalism and cultural revolution – what is the connection between these? Lin Piao would have us believe that the prevention of capitalist restoration is simply a matter of “ideological struggle,” of winning over men’s minds. Thus the whole purpose of the cultural revolution is distorted. The essence of cultural revolution is not simple ideological purification. No, cultural revolution is a necessary process in strengthening the socialist economic basis. Unless this relation between cultural revolution and the economic basis of society is grasped, we could very likely accept the notion that restoration of capitalism involves no more than the seizure of the leading posts in the state apparatus. In fact, seizure of these leading posts is only the first step and in many ways the least complicated step in the restoration of capitalism. The second step is the restoration of capitalism in agriculture. Following this (of course, not in a simple “1-2-3” chronological process) comes by far the most difficult, if not impossible, task, the dismantling of the entire Soviet state apparatus; i.e., the exclusion of the working class from economic planning. Until these three things have been accomplished, we must speak of restoration of capitalism, especially in the USSR today, in a contradictory way: yes, the Soviet Union is a social-imperialist state, in so far as the leading positions in the government have been seized by the Russian bourgeoisie; and no, capitalist restoration has not been entirely effected in the Soviet Union, precisely because the working class has not yet been entirely dispossessed. Let us examine this contradiction in more detail.

The question of the restoration of capitalism after the overthrow of the bourgeoisie has been a critical issues ever since the first workers’ state of the Paris Commune was overthrown a century ago. he Paris Commune taught the proletarian movement not only that they must seize state power but that the old, bourgeois state had to be thoroughly smashed. The dictatorship of the proletariat was from then on understood to be a qualitatively different type of state, in fact, “The Commune ceased to be a state in so far as it had to repress, not the majority of the population but a minority (the exploiters).”[15] The Paris Commune definitely did enjoy popular support as did the Soviet Government in the USSR. History has thus concretely proven that the dictatorship of the proletariat is the first state in the history of mankind which may enjoy popular support. May – because saying it does not make it so; because there is, more to the dictatorship of the proletariat than just the state apparatus; because winning the lasting support of the masses is something that can only be accomplished over a long period of time. It is true enough that during the insurrectionary period the first item of the agenda is the seizure’ of state power and the smashing of the old bourgeois state. This is what the Communards attempted to do, and in the process gave the world a glimpse of what socialist would be like in practice. The next glimpse did not come until 1917, when the Bolsheviks seized state power.

The first year of the Russian Revolution was one of decrees, nationalizations and intense revolutionary activity. The bourgeois world was momentarily stunned. But not for long. By 1920, fourteen nations had attacked the Soviet Union after a devastating episode in the First World War which cost millions of Russian lives and resulted in severe economic dislocation. The extent of this devastation was reported at a conference in Amsterdam in 1931.

The national economy of the Soviet Union suffered a severe decline as a result of the imperialist war and the civil war, as a result of internal counterrevolution and of the subsequent intervention by a number of capitalist countries. Industrial output, which was valued at 5.6 billion rubles in 1913, declined to 1 billion pre-war rubles in 1920. Agriculture also suffered severely. The sown area in 1916 was 281.6 million acres. By 1920 the sown area had decreased 25%, while the gross production of grain had decreased 50%. Railway transportation was completely disorganized. In 1913 there were 20,030 locomotives; in 1920-21 only 18,757 were left. The percentage of locomotives in disrepair increased from 16.3% in 1913 to 62% in 1921.[16]

Now the Soviet Union had to muster all her forces to fight off both her internal bourgeoisie and the foreign bourgeoisie with which it had united. The Bolsheviks did not have to invent any new ideas to see that classes and class struggle continued to exist after the seizure of state power by the proletariat; In fact, in 1920 Lenin put forth a clear analysis of the possibilities of capitalist restoration and the economic basis of the bourgeoisie under socialism.

The dictatorship of the proletariat is a most determined and most ruthless war waged by a new class against a more powerful enemy, the bourgeoisie, whose resistance is increased tenfold by its overthrow (even if only in one country), and whose power lies not only in the strength of international capital, in the strength and durability of the international connections of the bourgeoisie, but also in the force of habit, in the strength of small production.[17]

Thus the organizing role of the state in establishing the economic basis for socialism is laid bare. A state alone is all the proletariat has at first. But if it rests content with that, the proletariat will lose the state as well. This is why Lenin wrote, “Either we lay an economic foundation for the political gains of the Soviet State, or we shall lose them all.”[18] And what is the essence of this economic foundation and its relation to the state?

To make things even clearer, let us first of all take the most concrete example of state capitalism....It is Germany. Here we have ’the last word’ in modern large-scale, capitalist engineering and planned organization, subordinated to Junker-bourgeois imperialism. Cross out the words in italics, and in place of the militarist, Junker, bourgeois, imperialist state, put also a state, but of a different social type, of a different class content – a Soviet state, that is, a proletarian state, and you will have the sum total of the conditions necessary for socialism. Socialism is inconceivable without large-scale capitalist engineering based on the latest discoveries of modern science, etc.[19]

Why is large-scale industry so necessary to socialism? First, because without it, the division which exists between town and country under capitalism would continue to grow under socialism. Under capitalism, the country becomes subordinate to the town; agriculture always lags seriously behind the development of industry. It is not necessary here to go into all the reasons for this. Suffice it to say that the result is that thousands of peasants and farmers live on a subsistence income and those who cannot make it in the country flock to the cities in search of nonexistent jobs. In Latin America, for example, there are 60 million campesinos who make an average of 25 cents (USNA currency) a day. And surrounding the cities of Latin America are filthy slums in which live 50 million unemployed or underemployed workers.[20] There are the concrete results of the division between town and country. There are the conditions which the socialist state inherits. Without large-scale industry, these conditions cannot change. Agriculture cannot move ahead without mechanization. Fallow land cannot be made fertile again without fertilizer industries and scientific use of the soil. To put it simply, large-scale industry makes possible mechanization and rational use of land; these in turn make possible collectivization; collectivization is the bridge to the proletarianization of the peasantry and the abolition of classes in the countryside.

This division between town and country is quite dangerous for the socialist state because it leads to the most intense kind of profiteering and economic chaos. The socialist state does not do everything in its power to eliminate this division between town and country out of some liberal “humanitarian” motives. No, the elimination of this division is the life and death of socialism. This is particularly true in a country such as the Soviet Union or China, where small-scale production, especially in the countryside, was the dominant aspect of production. Small scale production has serious consequences both economically and socially, and these consequences are completely interrelated.

Economically, small-scale production provides the perfect environment for the regeneration of capitalism. First of all, social production is at a minimum. Each peasant has his own private plot and will fight to the end to save it. Once the harvests are in, each individual must sell his produce. The sale of his commodities for the greatest profit is the life and death of the individual proprietor. Thus the incredibly intense competition in the agricultural market. The only law which prevails in such a marketplace in which aspiring capitalists sell their goods is the production for maximum profit. Production for maximum profit goes hand in hand with anarchy of social production, the opposite of socialist economic planning. Because the overriding incentive for better production is profit, the result is overproduction of one variety of commodities after another. And the class that suffers from this the most is of course the proletariat, which survives from the food produced by these methods. Conditions are made even worse by the constant influx of peasants who come to look for nonexistent jobs in the cities after being driven out of business by the cut-throat competition. Dealing effectively with this type of production is a much more difficult and complex thing than nationalizing large-scale industry where the production has already been socialised, particularly in the Soviet Union and China where the vast majority of the population consisted of peasants. As Lenin pointed out, “The peasants constitute a huge section of our population and of our entire economy, and that is why capitalism must grow out of this soil of free trading. That is the very ABC of economics as taught by the rudiments of that science, and in Russia taught, furthermore, by the profiteer, the creature who needs no economic of political science to teach us economics with.”[21] These profiteers took advantage of the fact that the Soviet proletariat at that time was literally starving. They were hardly concerned about the need of the proletariat for grain. What mattered to them was the realizable demand of the proletariat; in other words, their ability to pay for the grain. Without this pay these profiteers withheld their grain from the market, smuggled it outside the Soviet borders and in general resorted to a variety of maneuvers to secure the highest prices for their goods.

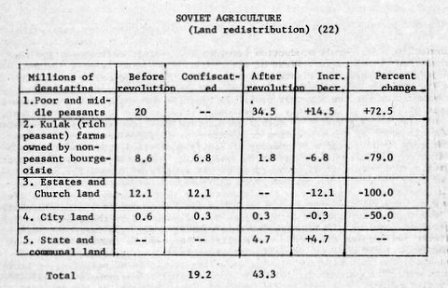

How, concretely, is this environment eroded away by the socialist state, undermined to the point that agricultural production is carried out by proletarian agricultural armies? The history of the Soviet Union shows us that this is first of all a process involving many stages. The first stage is of course nationalization of the land and supplying the ruined peasantry with land. The extent of this nationalization is shown in the following figures:[22]

Revolution meant the real liberation of the poor and middle peasants from the exploitation of the big landowners. It increased considerably their landholdings, and at the same time sharply reduced the burden of taxation by means of which the landowners’ government had additionally exploited these sections of the rural population. The middle peasant became the central figure in post-revolutionary agriculture.[23]

This liberation of the poor and middle peasants laid the basis for collectivization of agriculture. What did collectivization mean?

Collectivization involved the elimination of boundary strips and the formation of large land areas, which enabled the peasants to make better use of their means of production and apply machine methods more advantageously.[24]

The primary form this collectivization took was the artel type of collective farm. The artel was a form in which only the principal means of production were collectivized. An extremely important role in this was played by the machine and tractor stations which were set up all over the Soviet Union and China and Albania. For the first time the peasant had an opportunity to develop new land, not alone, but in cooperation with his fellow peasants. On this basis the collective farms could be united into larger and larger units.

The more successful these collective farms are, the more the real material basis is created to eliminate the wealthy capitalist elements in the countryside. So we can see that collectivization is not just a process involving solely peaceful forms of struggle. No, collectiviation of agriculture could only be accomplished through intense struggle against the rich peasants, or kulaks as they were known in the Soviet Union. At the same time, this collectivization had to be completely coordinated with the development of large-scale industry. The most concrete manifestation of the link between the industrial proletariat and the peasantry were the machine and tractor stations. But they could not have been built without steel mills, tractor factories, etc. The tractors could not run without the development of fuel resources. The grain could not be taken to the cities without locomotives. This is the economic basis for the alliance between the proletariat and the peasantry in the Soviet Union, China and Albania. Just to show how long and drawn out this process was, though, we quote from Stalin’s Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR, written 30 years after the NEP period:

But the collective farms are unwilling to alienate their products except in the form of commodities they need. At present the collective farms will not recognize any other economic relation with the town except the commodity relation exchange through purchase and sale. Because of this, commodity production are as much a necessity with us today as they were thirty years ago, say, when Lenin spoke of the necessity of developing trade to the utmost.

Of course, when instead of the two basic production sectors, the state sector and the collective sector, there will be only one all-embracing production sector, with the right to dispose of all the consumer goods produced in the country, commodity circulation, with its ’money economy’ will disappear, as being an unnecessary element in the national economy.[25]

The creation of a single production sector involves not just the transformation of an agrarian-industrial country such as the USSR or China into an industrial-agrarian country, but, also the development of true socialist relations of production. Socialist relations mean much more than the seizure of state power by the proletariat. Otherwise NEP would have been unnecessary. By socialist relations of production we mean the direct rule (ownership) over the means of production by the working class itself. Lin Piao, who blithely pronounced the complete restoration of capitalism in the USSR, did not deal with this important point. Under capitalism, the working class has no say in the management of the economy, except insofar as it fights for better conditions for the sale of its labor power. As a matter of fact, the capitalists as a class have no real control over the economy either in the sense of ability to solve the basic problems of capitalism, which despite sophisticated devices, manipulations, etc, operate according to objective laws which operate blindly and beyond the consciousness of the “masters,” who try in vain to avoid crises, depressions etc. The basic economic law of socialism – “the securing of the maximum satisfaction of the constantly rising material and cultural requirements of the whole of society through the continuous expansion and perfection of socialist production on the basis of higher techniques”[26] – is also an objective law, different only in the sense that the class in power, the proletariat, understands and can utilize it in a conscious, rational way, that, is, the law of socialism is consciously applied, in such a way that eventually millions of workers take part in consciously building the socialist economic basis. The socialist state plays an active role in building the socialist relations of production. In the USSR this took place under the State Planning Commission of the USSR, which coordinated the work of drawing up an economic plan for the entire country. The extent of participation of the workers in the drawing up and fulfillment of the plan is revealed here:

The single plan of national economy drawn up with the help of the masses and expressing the will of tens of millions of workers is actively carried out by them. The struggle for the fulfillment of the plan takes place on all sectors of the economic front. The numerous difficulties which arise during the drive for its fulfillment are overcome. The fulfillment becomes a matter of honor for the respective groups of workers in the various sectors, and becomes an object of competition among them. Every phase of the plan, every part of the task attracts the attention of millions of workers.[27]

The plan of national economy in the Soviet Union is a plan of the millions of workers. Millions of workers draw it up, carry it out, and watch closely the course of its development. This is the basis of success of planned economy. This is the fundamental advantage of the Soviet system of economy. This is the source of the unprecedented rate of development in the Soviet Union.[28]

By the time Stalin died over 100 million people were involved in this process. What the complete restoration of capitalism means is the disenfranchisement of these millions of workers. It means the dismantling of all the Soviets, of all the planning bodies within each factory and farm. So we see that restoration of capitalism after 40 years of socialism is not so easy as it may seem. It isn’t just a question of control of the Central Committee; it is a question of transforming perhaps the most all-embracing, popular administrative apparatus in history into a tool of a tiny minority of the population.

That is why the bourgeoisie in the USSR and China concentrate on revising the basis of agriculture before demolishing this entire administrative apparatus in their attempts to restore capitalism. It is in agriculture that small-scale production still has a hold. Small-scale production, as we have seen, provides initially the most favorable soil for the growth of capitalist elements. In the Soviet Union, China and Albania, the bourgeoisie well understands that because of the historical development of these countries, agriculture and the small-scale production which in part characterizes it is the weak link. Once we understand the effects of small-scale production on the economic basis, then we are in a position to see its effects on the superstructure – the state, culture, ideology and so forth. The social counterpart of small-scale production is well known. Illiteracy, cultural backwardness, bribery and corruption on all levels. Bourgeois sociologists like to argue that these traits are national in origin and similar claptrap. But anyone who has lived in or seen an industrially underdeveloped country can immediately see that this is hardly the case. Others assume that these traits arise from the state apparatus itself, or, using even more shallow reasoning, from “bad ideology,” “revisionist thinking,” etc. This is the deviation which concerns us, since it is so prevalent in the left today, and here again it was Lin Piao who summarized many of its basic tenets.

As we have said, China was forced to follow a similar path as far as collectivization of agriculture and the development of large-scale industry were concerned, to that of the Soviet Union. And just as in the Soviet Union, there were those in the Communist Party of China who, representing the interests of the bourgeoisie, realized that an attempt at restoration of capitalism was just so much empty talk without an attack on the collective farms. This was the case with the infamous traitor Liu Shao-ch’i. By the time he was finally purged from the Communist Party of China and from the government he and his thousands of followers throughout China had succeeded in wreaking havoc in the collective farm movement. It is no accident that the focal point of this attack was the return of all collectivized property to individual ownership. This could not be done openly, as the Soviet revisionists are trying to do it today, but secretly and deviously. Why did Liu Shao-ch’i concentrate on agriculture? Imagine returning an industry to private ownership under socialism. First of all, industry, especially large-scale industry, is the most nationalized sector of the socialist economy. In the Soviet Union, for example, we have the following figures as early as 1926-7: “...A total of 91.3 per cent of industry covered by the census was state industry, 5% was cooperative industry and only 2.3% was private capitalist industry.”[29] Under capitalism the owners of industries and banks constitute by far the smallest class in the population. Under socialism they are dispossessed altogether. Further, there is no social basis for the reversion of capitalism in industry. In industry you are dealing with a capitalist who employs many laborers and who cares less whether he makes radios or popcorn as long as he turns a good profit. In agriculture, you are dealing with a peasantry the majority of whom are not exploiting the labor of others - that is, the poor and middle peasants. They are tied to their land which is the only thing they have and which they will not give up unless they are convinced that doing so will benefit them. That is why Liu Shao-ch’i basically oriented his followers toward agriculture. This does not mean, however, that he didn’t advocate the destruction of socialist large-scale industry too. He did that too, urging total reliance on light industry because it was more “profitable” than heavy industry. Small, light industry is, once it is isolated from heavy industry and set in opposition to it, the complement of an anarchic market economy in agriculture. The two factors operating simultaneous create the proper environment for the attempt to restore capitalism.

The very first place where Liu had to be defeated was in the state apparatus. This is what the event we call the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was all about. It was the focal point of the cultural revolution that is a permanent institution in every socialist country. It was a continuation of the class struggle that is still continuing in China. It spelled the doom of the large capitalist elements in the countryside, firstly by smashing their niche in the state apparatus, as well as by continuing to develop socialist relations in the collective sector. The battle was focused on the bureaucracy within the state apparatus, the corruption of state officials who were following Liu Shao-ch’i’s dictates, etc. By the involvement of millions of peasants in the revolution further to consolidate state power the link between the bureaucracy and corruption in the government and party, on the one hand, and petty small-scale production, on the other, was revealed.

It was only natural for the bourgeoisie to try to conceal this link. After all, they had to do everything possible to protect their economic basis. Enter Lin Piao. The first item on his agenda was to isolate the Cultural Revolution from history, to make it seem like something special that had never happened before. He tried to do this in 1967 when he wrote the following:

China’s great proletarian cultural revolution has won a decisive victory. In the history of the international communist movement, this is the first great revolution launched by the proletariat itself in a country under the dictatorship of the proletariat. It is an epoch-making new development of Marxism-Leninism which Chairman Mao has effected with genius and in a creative way.[30]

Lin’s main hope here was to convince people that Mao was creating something new, that there was no use even seeing what Lenin and Stalin had to say on the subject because they had not even thought about it. But once we firmly reject that line we can see right away that here again Mao Tse-tung did no more – and no less! – than consistently apply the teachings of Lenin and Stalin on the cultural revolution.

Lenin pointed out in 1921 that the economic basis of socialism could not be built without raising the cultural level of the masses. “The task of raising the cultural level is one of the most urgent confronting us,” he said[31], and “We also need the culture which teaches us to fight red tape and bribery. It is an ulcer which no military victories and no political reforms can heal. By the very nature of things, it cannot be healed by military victories and political reforms but only by raising the cultural level.”[32] Now what is Lenin talking about if not cultural revolution? But, the argument goes, the Chinese’ cultural revolution was the first actively to involve millions. Lin Piao says it in the following way: “This extensive democracy is a new form of integrating Mao Tse-tung’s thought with the broad masses, a new form of mass self-education. It is a new contribution by Chairman Mao to the Marxist-Leninist theory on proletarian revolution and proletarian dictatorship.”[33]

Here we have to return to one of the main points of the cultural revolution – the elimination of the rich landlords’ economic power in the countryside. In this respect the Chinese Cultural Revolution is very similar to that which brought about the elimination of the kulaks in the Soviet Union between 1928 and 1930. And was this something done simply by the Party alone, without the broad participation of the masses? No. “The distinguishing feature of this revolution was that it was accomplished from above, on the initiative of the state, and directly supported from below by the millions of peasants, who were fighting in freedom to throw off kulak bondage and to live in freedom in the collective farms.”[34] So it is that here too Mao applied the historical experience of Marxism-Leninism to the concrete conditions within China. It should be added that here too the CPSU expresses the correct relation of the party and the working class in the cultural revolution. So long as classes exist, the Party must never relinquish its leading role; it must never be led by the proletariat, but must always lead it. At the same time it can only lead it by involving millions of workers and peasants in the class struggle in a conscious way. Lin Piao’s formulation that the cultural revolution was initiated by the proletariat is not only in contradiction to reality but denies the leading role of conscious Marxist-Leninists. And the argument that Liu Shao-ch’i controlled a large part of the Party holds no water here. The Cultural Revolution proved beyond a doubt that the vast masses of Marxist-Leninists were loyal to their class science and not to him.

The cultural revolution in the Soviet Union did not just involve the transformation of the economic basis, but also of the superstructure. It involved compulsory education for millions of children and workers, an end to illiteracy, abolition of national and sexual privileges, etc. The History of the CPSU is quite clear on this point: “This was a veritable cultural revolution. The rise in the standard of welfare and culture of the masses was a reflection of the strength, might and invincibility of our Soviet Revolution. Revolutions in the past perished because, while giving the people freedom, they were unable to bring about any serious improvement in their material and cultural conditions. Therein lay their chief weakness. Our revolution differs from all other revolutions in that it not only freed the people from tsardom and capitalism, but also brought about a radical improvement in the welfare and cultural condition of the people.”[35]

The more we study the history of the Chinese and Soviet Revolutions, the more we see that the former is a continuation of the latter. The Marxist-Leninists of both countries confronted the same basic problems and solved them in the same basic way. This is only natural since they were, as we have said, Marxist-Leninists and not Stalinists or Maoists.

The one thing that really stands out in this history is that the cultural revolutions of both countries were hardly for culture alone. The improvement in cultural standards cannot be separated from the improvement in material standards. The fight in the super structure goes hand in hand with the fight to change the economic basis and develop the productive forces. It is precisely this fact that Lin Piao was so anxious to conceal. His separation of the Chinese Cultural Revolution from the Soviet cultural revolution attempted to lay the basis for this much more fundamental deviation. As we stated before, Lin Piao as a representative of the Chinese bourgeoisie had to conceal and protect the capitalist elements in the economic base, particularly those who had been given a new lease on life by Liu Shao-ch’i and his ilk. The best way to do this? Make it seem that the whole cultural revolution was only concerned at the most with the state apparatus and at the least with ideology in general, in the abstract, isolated from material production and the state as well. Make it seem that bureaucracy and red tape had their basis in the socialist state apparatus. Here is where the separation of Mao from Lenin and Stalin and the separation of the Chinese from the October Revolution really pays off. For Lin Piao uses none other than Lenin himself to “justify” his theory. He gives us the following quote: “Lenin also stated that ’the new bourgeoisie’ was ’arising from among our Soviet government employees’.”[36] Now let us look at the entire quote in the original text and see what Lenin was really saying:

For instance, Comrade Rykov, who is closely familiar with the facts in the economic field, told us of the new bourgeoisie which have arisen in our country. This is true. The bourgeoisie are emerging not only from among our Soviet government employees – only a very few can emerge from their ranks – but from the ranks of the peasants and handicraftsmen who have been liberated from the yoke of the capitalist banks, and who are now cut off from railway communication.... It shows that even in Russia, capitalist commodity production is alive, operating, developing and giving rise to a bourgeoisie, in the same way as %t does in every capitalist society.

Comrade Rykov said, ’We are fighting against the bourgeoisie who are springing up in our country because the peasant economy has not yet disappeared; this economy gives rise to a bourgeoisie and to a capitalism.’ We do not have exact figures about it, but it is beyond doubt that this is the case. ([37], emphasis mine)

By extracting a couple of sentences from Lenin and using them out of context, Lin Piao managed to distort the whole Marxist-Leninist theory on the source of strength of the bourgeoisie after the seizure of state power by the proletariat. The essence of this revisionist line is that the “new” bourgeoisie, grows out of the socialist state apparatus. Why? Because, it is claimed, the socialist state apparatus is a bureaucracy. And bureaucracy, as everyone knows, breeds bourgeois elements. But can’t we smell a rat here?

First of all, what is bureaucracy? Everyone knows that every state apparatus has administrative bureaus. Under capitalism and especially with the advent of its moribund stage, imperialism, these bureaus become the end-all and be-all of government. Every imperialist governmental official operates strictly from the point of view of preserving his particular bureau, his niche in the governmental apparatus, regardless of whether or not it is in the interests of the general population, which it seldom is. This is bureaucracy* A bureaucrat is not simply someone who is in charge of a bureau, or else we would have to call Stalin, head of the Political Bureau of the CPSU (B), a bureaucrat. A bureaucrat preserves himself by separating himself and his bureau from the masses of workers and peasants, whether under capitalism or socialism. The ideological basis of the bureaucrat is distinctly capitalist. That is why Lenin pointed out:

In a Socialist society, this ’something in the nature of a parliament,’ consisting of workers’ deputies, will of course determine the conditions of work, and superintend the management of the ’apparatus’ – but this apparatus will not be ’bureaucratic’ The workers, having conquered political power, will break up the old bureaucratic apparatus, they will shatter it to its very foundations, until not one stone is left upon another; and they will replace it with a new one consisting of these same workers and employees, against whose transformation into bureaucrats measures at once will be undertaken...[38]

Secondly, bureaucracy has to have some kind of material basis. Where does that leave us if we assume that the material basis of the bourgeoisie is the socialist state apparatus? We are saying then that the socialist state is basically the same apparatus as the capitalist state, only that it is controlled by the proletariat instead of the bourgeoisie. But the line of Marxism-Leninism on this is that the difference between the socialist and capitalist state is not only quantitative but qualitative. Lenin wrote of the Paris Commune: “Here we observe a case of ’transformation of quantity into quality:’ democracy, introduced as fully and as consistently as is generally thinkable, is transformed from capitalist democracy into proletarian democracy; from the state (i.e., a special force for the suppression of a particular class) into something that is no longer really the state in the accepted sense of the word.”[39] The bureaucracy that does exist in the socialist state apparatus is not something that is spawned by this apparatus in and of itself. It is a hangover from capitalism, whose bourgeoisie needs a well-developed bureaucracy to keep the class struggle in check and to suppress the proletariat. It develops under capitalism because the bourgeois state is a parasite on society. Capitalist state officials are paid many times more than the average factory worker. They are subject to the more incredible bribes and corruption in various forms. Is this the case with the socialist state officials? In general this cannot be said. The socialist state is the only state in the history of man that has the potential to eliminate bureaucracy, to eliminate the gap between the state official and the factory worker. To go into all the ways it does this would take a whole other article, but one need only study Lenin’s State and Revolution and the history of the Soviet state to see that this is indeed the case. Of whom did the bureaucracy in the Soviet state apparatus consist? Bureaucracy was practiced either by officials who were inexperienced and whose cultural level was low, or else, more importantly, by capitalist elements who wormed their way into the state apparatus. The latter group, we should remember, did not sneak into this apparatus primarily because of laxness on the part of the Bolsheviks. During the early years of the Revolution, especially during NEP, they had to be invited back in order to stabilize the economy and restore large-scale industry. Once NEP was over, by 1923, these elements were swiftly being replaced by proletarians who had been trained to handle their jobs. As was to be expected, the>former did not give up their privileged positions without a fight. Interestingly enough, this fight was carried out under the Trotskyite slogan of “smashing bureaucracy.” The Trotskyites were really out to smash the Bolsheviks and establish themselves, the real bureaucrats, as the rulers of the USSR under the direction of Nazi Germany. Of the many examples of this, we shall cite one. The Trotskyites always proclaim that during the purges conducted in the CPSU(B) during the latter half of the 1930s many innocent communists were purged or put on trial. This proves, they claim, that the Soviet State was bureaucratic. But what they neglect to tell us about is that not-so-well-known fact that the head of the Soviet secret police for part of this period was none other than Yagoda, a member of the secret bloc of Rights and Trotskyites, who was later exposed and removed from the stage of history. Is it any wonder that this Yagoda did not prosecute the real Trotskyites, but in fact went after innocent communists, that is, whenever he could get away with it? He himself ordered the release of Kirov’s assassin three days before Kirov himself was shot and the former had been caught red-handed with a map of Kirov’s route to the office and a gun. We could give other examples, but the point is already clear. In both China and the USSR, generally speaking, bureaucracy, bribery and corruption were resorted to by the capitalist elements who had wormed their way into the state. They used bureaucracy as a means of undermining the authority and prestige of the Soviet state apparatus in the eyes of the workers and peasants, as a means of creating the right environment for an attempt at restoration of capitalism!

The basis of bureaucracy in the Soviet Union and China was not, as Lin Piao and his “left” followers around the world assert, in the Soviet state. Lenin made this clear enough: “In our country bureaucratic practices have different economic roots, namely, the atomized and scattered state of the small producer with his poverty, illiteracy, lack of culture, the absence of roads and exchange between agriculture and industry, the absence of connection and interaction between them.”[40] No wonder that Lin Piao did not bring this aspect out and as a matter of fact distorted Lenin in order to hide this connection. In doing so he was protecting his own economic basis, the basis of the Chinese bourgeoisie. It is indeed unfortunate that so many people have accepted Lin’s projection on the restoration of capitalism lock, stock and barrel. They think that one need only to look for “bureaucracy” in the state apparatus to see whether or not capitalist restoration has been effected. They think that the cultural revolution affects only the superstructure and not the basis. Most unfortunately of all, they have applied this empirical method to their analysis of the Soviet Union, saying nothing different from what Lin Piao said, that is, that Brezhnev, Kosygin and company have brought about an “all-round restoration of capitalism in the Soviet Union.”[41] Thus with a stroke of the pen Lin Piao declares that both the state and the basis of socialism have been completely eliminated, and with them 40 years of socialism.

We reject such simplistic notions of restoration of capitalism in the USSR or China. Taking over the socialist state is one thing; converting a socialist economic base back into a capitalist one is a horse of a different color and can never be done – if indeed it is really possible to do it at all – by a coup d’etat such as brought the bourgeoisie to power after Stalin’s death.

Secondly, we recognize that the dictatorship of the proletariat is not a brief historical event. As Lenin pointed out:

The transition from capitalism to Communism represents an entire historical epoch. Until this epoch has terminated, the exploiters inevitably cherish the hope of restoration, and this hope is converted into attempts at restoration. And after their first serious defeat, the overthrown exploiters – who had not expected their overthrow, never believed it possible, never conceded the thought of it – throw themselves with energy grown tenfold, with furious passion and hatred grown a hundred-fold, into the battle for the recovery of the ’paradise’ of which they have been deprived...[42]

Lenin makes it “perfectly clear” that this transition involves intense class struggle, one which produces not only Lenins and Stalins but Brezhnevs and Kosygins. To say that the restoration of capitalism has been completed in the Soviet Union, to say that the Soviet Union is a “superpower” exactly like the USNA, is to deny the intensity of class struggle inside the Soviet Union. It is a denial of the reality of the temporary hegemony of the USNA over the imperialist world. This line contends that the world today is characterized mainly by a struggle between “rich – superpower” nations and “poor – third world” nations. We do not here have to go into all the consequences of this argument, except to say that it places the proletariat of each nation under the hegemony of its own bourgeoisie, a notion we communists emphatically reject. Finally, we reject this line because it is a complete denial of the revolutionary role of the socialist state and the communist party which guides it. When we strip the argument of all its frills we are left with the same old bourgeois idealist claptrap: Power corrupts. Isn’t this what the bourgeoisie says about every proletarian revolution? “Just you wait. You may be very progressive and revolutionary now, but after a while you’ll become just like us, bureaucratic and separated from the masses whom you claim to serve.” If Lin Piao had stated his position in these words it would have been rejected outright. But he was too clever to do that. Instead he took advantage of the theoretical backwardness of the international communist movement, and was able to substitute a simplistic notion for a very complex process. And it should be kept in mind that this article is only going into the barest detail on the question of cultural revolution and capitalist restoration. But even so we can learn a very important lesson from Lin Piao, that is, that we must train ourselves to look beneath the “Marxist” trimmings of things, because today especially we find all sorts of notions parading around under the banner of Marxism. Whether or not they are indeed Marxism demands of us study and theoretical analysis applied to concrete conditions, and not the blind acceptance which Lin urged on his followers all over the world.

“In the final analysis, the national question is a class question.” This is an axiom of the communist movement. It implies that the fundamental contradiction in the world today is a class contradiction between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. That is why we strive for unity of all proletarians, regardless of nationality. But to achieve it we must recognize disunity along national lines. Therefore we support all national liberation struggles which push the proletarian movement forward and objectively hinder imperialism. Further, history has proven that the national bourgeoisie of the colonies is too weak to lead such a movement successfully. In order to defeat imperialism the proletariat must have hegemony in the movement.

Since the end of World War Two there has been, without question, an upsurge of national liberation movements against imperialism, particularly USNA imperialism. The revolutionary wars being fought in Southeast Asia now and for the last decades have brought millions of people into revolutionary politics. Is it any wonder then that the bourgeoisie is doing everything within its power to lead the national liberation movements onto the wrong trail? On the one hand they oppose them with force of arms. On the other, they subvert these struggles, the main agent of this subversion being international revisionism, headed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In the last twenty years the Marxist-Leninist line on the national-colonial question has become so distorted and twisted in some sections of the left movement that it has become almost unrecognizable. It has been transformed into an eclectic hodge-podge of populist, syndicalist and nationalist “theories” which have nothing in common with Marxism. And here again we find Lin Piao playing his role as the adept servant of the Chinese and Soviet bourgeoisie. It is unfortunate in a way that Lin did not write more on the national and colonial question; we would have been able to expose him all the more thoroughly. What little he did write, however, will serve as a good enough basis for our argument. In fact, it provided the impetus for a full-blown deviation on this important question, a deviation that placed the colonial revolutions under the hegemony of the national bourgeoisie in the colonies and condemned the proletariat to a passive, spectator role. It is a deviation which fundamentally rejects proletarian internationalism, proposing that the socialist revolution can be brought about by one nation defeating another nation instead of one class defeating another class. It leads straight to the “Third World” line which projects these two theses: 1) the colonial national bourgeoisie, in spite of the advance of history since the October Revolution, is capable of leading a real struggle to smash imperialism; and 2) the proletariat of the oppressor countries cannot forge an alliance with the proletariat and peasantry of the oppressed nations, for the only battle in the world today is between the “superpowers” and the “Third World.” And just as before, there is enough Marxism in Lin Piao’s argument to confuse the issue and hide the deviation.

To begin with, he begins his argument in the familiar way, separating the Chinese Revolution from the October Socialist Revolution in order to justify “new” theories. In “Long Live the Victory of People’s War” he writes, “The victory of the Chinese people’s revolutionary war breached the imperialist front in the East, wrought a great change in the world balance of forces, and accelerated the revolutionary movement among the people’s of all countries. From then on, the national liberation movements in Asia, Africa and Latin America entered a new historical period.”[43]