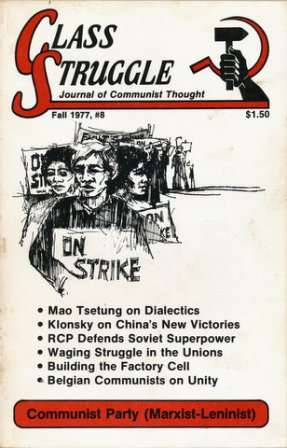

First Published: Class Struggle, No. 8, Fall 1977.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

Centrism continues to pose as a middle force–in between Marxism-Leninism and revisionism.

Is a group like the Guardian newspaper basically a middle force that jumps back and forth between one camp and the other? Or is it basically a variant of revisionism which is fundamentally opposed to the revolutionary movement?

The struggle with the Guardian centrists has clearly demonstrated the latter.

Yet completely erroneous answers to these questions appeared in an article by the revisionist Martin Nicolaus in Class Struggle, Number 3. Called “The Guardian’s Man in Havana: An Exposure of Centrism,” the article does just the opposite of what the title proclaims. In fact it is a cover-up of centrism and a hidden defender of revisionism.

The revisionist line of Martin Nicolaus, however, was by no means limited to his views on centrism. As many articles in The Call and Class Struggle have pointed out over the past year, there was no area in the political line and practice of this renegade that was unaffected by revisionism. Nicolaus completely reversed the relationship between friends and enemies of the working class. While displaying great love for alliances with the liberal bourgeoisie, he promoted the chauvinist liquidation of the strategic importance of the movements of the oppressed nations and national minorities.

Nicolaus’ bankrupt views on all these questions come out in his phony polemic with the Guardian. His stated purpose is to expose the “essence” of centrism by examining the “contradictions” between the Guardian’s “words and deeds” during the participation of its editor, Irwin Silber, at the Havana Conference on Puerto Rico. In this case, centrism is defined as the “hopeless effort to reconcile the movement to form a new communist party with the politically rotten, moribund forces of revisionism and Soviet social-imperialism. ”[1]

Nicolaus then spends most of his article criticizing Silber’s tactics in Havana, mainly the fact that he abstained from standing up to vote for the overall document adopted by the gathering. He portrays the Guardian’s political line, however, as still Marxist-Leninist, with the exception of a growing number of “positions” where it had recently conciliated to or found unity with the revisionist Communist Party (CPUSA). This leads him to presenting centrism as a third political line, a “mediator” between Marxism and revisionism, a mixture of Marxist-Leninist declarations” and opportunist tactics. As Nicolaus sums it up, centrism is “the strategy of ’fighting’ revisionism by sleepwalking into revisionist and social-imperialist traps.”[2]

But Silber is certainly no “sleepwalker.” This false criticism only covers over the fact that centrism is itself a particular form of revisionism. Although revisionism can take on any number of different forms–such as centrism, economism, ultra-leftism, dogmatism-its basis is the same. It is the ideology of the bourgeoisie within the working class movement under the guise of Marxism-Leninism.

At bottom there is no great contradiction between the “words and deeds” of centrism. Its ideological and political line, the basis for all its strategy and tactics, is revisionism, not hypocrisy. Its special danger consists of its “anti-revisionist” pose, which gives it more credibility among revolutionary-minded people than the openly revisionist CPUSA. That is why centrism must be treated very seriously, and not dismissed with a few mocking phrases.

At the same time, this bourgeois force must be despised and isolated strategically. By describing the Guardian’s politics as merely “spineless,” Nicolaus portrays it as an unreliable and vacillating ally, but an ally nonetheless. Moreover, by describing the Guardian as “isolated . . . from the major trends and organizations that have arisen within the Marxist-Leninist movement,” he downplays the danger of centrism tactically.[3]

Nicolaus’ article is a good example of this underestimation of centrism. Commenting on Silber’s refusal to vote on the final document, it says that “the Guardian representative stopped a couple phrases short of full endorsement of the Soviet social-imperialist position.”[4] Nicolaus never says, however, what these “couple of phrases” were and what the actual significance of Silber’s stand toward them was. From the beginning, Silber made it clear that his only reservation about the Conference was that “the revisionists are bound to try to define the Conference in terms of ’detente’ ” but that this was only a “secondary aspect” in its importance.

What Nicolaus covers up with his bombast about “spinelessness” is the revisionist line behind Silber’s maneuver. The fact is that the Guardian does not consider the Soviet Union to be an imperialist power, does not consider the Soviet Union to be a source of imperialist war, and does not view “detente” as a mask for its imperialist war preparations. Beneath all its “anti-revisionist” phrasemongering, then, the Guardian’s actual view is that the Soviet Union is a socialist country. It follows, then, that the Soviet Union was rendering “proletarian internationalist” assistance to the struggle in Puerto Rico, despite its making a secondary tactical error of “pacifism” and “chauvinism” in using the Conference to promote “detente.” Silber then used this “difference” with the Russians to mask his own 100% agreement with the basic aim of the Conference, which was to firm up an alliance between a number of Puerto Rican independence organizations and the Soviet social-imperialists. This is why Silber so viciously attacked those who exposed this feature of the Havana gathering and his loyal oppositionist role within it.

Just as he covers up for the centrists in this way, Nicolaus also presents an incorrect view of the CPUSA revisionists. He describes them as but a “tin can tied to the social-imperialist juggernat” that “can never gain leadership over the mass of workers and other progressive people with its pro-Soviet social-imperialist position.”[5] Likewise for the Soviet Union: “The only political line that has even an outside chance of winning for Soviet social-imperialism some remnants of the mass influence the Soviet Union once had when it was a socialist country is precisely centrism.”[6] But the Havana Conference showed that the CPUSA and the Soviet Union still have considerable influence in their own right and are especially dangerous to the anti-imperialist movement. In fact, by portraying them as tactically “weak” and “isolated,” Nicolaus undermines the very basis for aiming the main blow at the Soviet social-imperialists internationally and the revisionist and reformist trade union bureaucrats in this country.

But Nicolaus not only presents an incorrect view of the Soviet social-imperialists in his article. The Havana Conference, after all, was a product of the contention between the two superpowers, while Nicolaus only discusses the ambitions of one of them. He rants and raves about the relation of centrism and revisionism to the Soviet Union, but ignores their relation to the U.S.

The struggle in the Puerto Rican Solidarity Committee, for instance, did not only revolve around the question of whether or not to promote an alliance with Soviet social-imperialism. Two lines also emerged on the following question: Should the movement in support of Puerto Rican independence in the U.S. be built on the basis of making a reformist, “humanitarian” appeal to liberals in Congress? Or should it be built mainly among the working class and oppressed nationalities, targeting the imperialists as the cause of colonialism and national oppression?

Nicolaus’ unity with the CPUSA, the Guardian and the U.S. branch of the Puerto Rican Socialist Party (PSP) in one revisionist bloc can be seen even further by examining this question concretely. Since the Havana Conference, for example, the main activity of the PRSC has been applying pressure on Congress through petitions, press conferences and demonstrations for the passage of the Dellums Amendment. This measure is nothing but a reformist scheme which calls on Congress voluntarily to cede independence to Puerto Rico. In fact such a program would do just the opposite. It would sabotage the independence movement by promoting an alliance with and reliance on liberals like President Jimmy Carter, who talks about “self-determination” for Puerto Rico only to prolong U.S. domination of the island.

While the CPUSA and the PSP have been openly promoting this plan, the Guardian has never criticized it and in fact has gone along with it ever since it was put forward more than a year ago. Together with this, it is no longer any big secret that the PSP now considers Herman Badillo, reformist Democratic Congressman from New York and long-time opponent of the independence movement, to be a progressive force in its new “anti-annexationist” united front.

PSP’s analysis is that the U.S. bourgeoisie is split into two sectors, one which is “interested in forcefully imposing statehood” and another which “visualizes the same objective but with a great deal of subtlety and political and legal sophistication.”[7] The respective spokesmen of each sector are Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter.

It is obvious to Marxist-Leninists that the main target of their fire should be directed at the more “subtle” and “sophisticated” line, exposing and isolating its representatives in the people’s movements. Not so for the PSP, which insists, both for itself and the PRSC, on “concentrating efforts on an anti-statehood campaign to counter the U.S. government’s pro-statehood offensive.” This is what opens the door to Rep. Ronald Dellums (D.-Calif.), then to Badillo and finally even to Jimmy Carter.

The PSP cannot praise the Dellums Amendment highly enough. Because of it, “Congress will be obligated to hold public hearings” and these hearings “will be one of the most important forms of struggle the Puerto Rican people will count on.”[8]

Isn’t this a nakedly revisionist line? Isn’t it clear now that the Havana Conference was a turning point and that “united action” with revisionism and Soviet social-imperialism has its price?

The PRSC’s praise for Dellums is also quite open. It states in the February 1977 issue of its bulletin: “Ronald Dellums is not a rich beer industrialist (in contrast to a congressman supporting Puerto Rican statehood). He is a Black congressman from a working class district, a district with a politically developed population, a district which was influenced by the emergence within its midst of the Black Panther Party and by its proximity to the Berkeley campus, one of the birthplaces of the movement to end the war in Vietnam. A progressive district. When Dellums introduced the resolution which calls for U.S. out of Puerto Rico, he was not representing imperialism. He was representing the people of his district and millions of others throughout the country who oppose all oppression.”[9] This is the kind of slick public relations job the revisionists always carry out for their favorite reformists. One must ask the PRSC: Who was Dellums representing when he encouraged the working class and oppressed nationalities to cast their votes for Jimmy Carter? And how did that help build a solidarity movement against imperialism?

Nicolaus, of course, cannot be criticized for failing to mention political events and developments which have transpired since his article was written. It is no accident, however, that he fails to target the line which guided these later developments: revisionism’s promotion of an alliance with the U.S. bourgeoisie’s liberal representatives. The reason? Because this fits right in with his own revisionist thesis that since the U.S. working class had no direct allies, such as the oppressed nationalities, it had to focus its attention toward its “indirect allies,” such as the liberals in Congress or the trade union bureaucracy.

To sum up: By pretending to expose centrism, Nicolaus in fact opposed the basic teachings of Marxism-Leninism on the class struggle and the role and features of revisionism in the workers’ movement. In exposing the Trotskyites of his day, Stalin put the matter well:

In the present period of acute class struggle, there can only be one of two possible policies in the working-class movement; either the policy of Menshevism, or the policy of Leninism. The attempts of the opposition bloc to occupy a middle position between these two opposite lines under the cover of ’left’ revolutionary phraseology and while intensifying criticism of the CPSU (Bolshevik) were bound to lead, and have actually led, to the opposition bloc slithering into the camps of the opponents of Leninism, into the camp of Menshevism.[10]

This is precisely what has happened to Nicolaus and the fellow members of his revisionist bloc. They are the Mensheviks of today, and they are bound to slither to the same fate as their historical forerunners.

[1] Martin Nicolaus, “The Guardian’s Man in Havana: An Exposure of Centrism,” in Class Struggle No. 3 (Chicago: October League, 1976), p. 47.

[2] Ibid., p. 60.

[3] Ibid., p. 55.

[4] Ibid., p. 57.

[5] Ibid., p. 57.

[6] Ibid., p. 58.

[7] Claridad: Bilingual Supplement, January 16, 1977, p. 9.

[8] Ibid., p. 8

[9] Puerto Rico Libre!, Bulletin of the Puerto Rican Solidarity Committee, February, 1977, p. 16.

[10] J.V. Stalin, “The Opposition Bloc in the CPSU (B)” in Collected Works, (Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1954), Vol. 8, p.242.