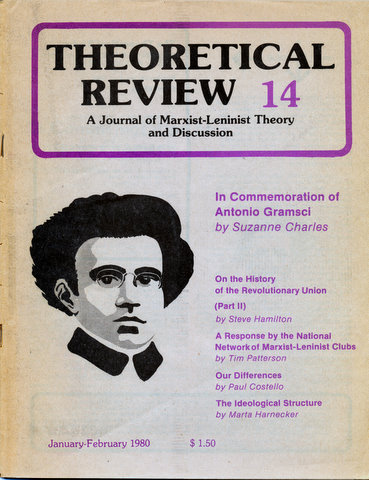

First Published: Theoretical Review No. 14, January-February 1980.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The recent joint critique of “The Party Building Line of the National Network of Marxist-Leninist Clubs” by the Tucson and Boston Theoretical Review editorial boards (TR #11) sets a good example for our movement of how principled ideological struggle can unfold in the present period.

We refer here not simply to the tone of the critique. Equally important is the fact that the TR comrades do more than pay lip-service to the formulation that party building is our central task. They take up the question of party-building line directly, put forward their views and challenge the views of others in a frank fashion.

Most importantly, the TR comrades recognize that the different party-building lines now in contention in our trend necessarily set the orientation for all of our principal tasks of this period.

Unfortunately, the good example set by the TR critique has not been emulated widely in our trend, particularly by the leading forces of the OCIC, who have chosen the path of caricature and obfuscation in taking up the content of the “rectification” line.

The TR critique, therefore, should be welcomed not only by the Club Network but by all the forces seriously grappling with the difficult problems our movement faces.

Although the TR critique focuses on an evaluation of the rectification line, it must also, of course, be seen as a further elaboration of the TR’s own distinct party-building line, identified as the “primacy of theory” line. The Ann Arbor/Tucson/TR forces have made significant contributions to the critique of the fusion line on party building. The forces in Tucson and Boston associated with the Theoretical Review have translated their line’s commitment to theoretical work into a concrete institution. – the TR – which is, to date, the only theoretical journal consciously addressed to our trend. The TR critique of the rectification line, then reflects the cumulative development of the primacy of theory line.

In exchanges such as this, the major emphasis – quite properly – is on real or apparent differences, their implications and the struggle for their potential resolution. This is particularly appropriate since the “primacy of theory” and “rectification” lines may seem indistinguishable to many comrades in the movement. But, agreement on the decisive role of the theoretical struggle for a correct political line rapidly gives way to significant differences over the thorny question of what kind of theory? Produced how? Under what conditions? By whom? It is to the perspective advanced by the TR in these areas that our response must be addressed.

We begin by enumerating briefly a number of critical areas of agreement:

* The main points of a common critique of the “fusion line,” targetting it as a right error in party-building line and drawing out its inherent tendencies toward economism, empiricism and pragmatism;

* The fusion line’s incorrect assessment of the mistakes of the New Communist Movement groups’ party-building/line and practice, emphasizing in particular the prevalence of earlier “fusion” lines in the approach of the RU, OL, etc.;

* The recognition of the line of demarcation which has occurred objectively in what was once a single, anti-revisionist movement;

* The identification of right errors as the main danger to the party-building movement in the present period, errors represented in the fusion line, the incomplete break with revisionist formulations and the general tendency toward empiricism in our movement;

* The necessity to distinguish between the particularities of a pre-party period and a period in which there is a genuine party, in opposition to the “fusion” line’s assertion that the practice of fusion is primary and essentially identical in both periods;

* The primacy in a party-building period of the struggle among Marxist-Leninists, not the struggle of Marxist-Leninists within the working class; and

* Despite obvious differences, agreement in several particulars on the inability of the Organizing Committee for an Ideological Center (OCIC) to solve the outstanding theoretical problems facing the movement.

And, or course, there is agreement on the fundamental perspective of the primacy of theoretical tasks in the process of party building.

The TR critique can be divided into two general areas: the approach to and the nature of our theoretical tasks in this period; and the proper orientation to the organizational aspect of party building – such as the role of leadership, the character and origin of a leading ideological center and the NNMLC’s decision to remain outside the OCIC.

For communists, theoretical work is always taken up for practical political reasons. The task of changing social reality is, in general, what sets the theoretical agenda for Marxist-Leninists.

In our view, the principal political task of the period is the re-establishment of a genuine communist party in the U.S. The principal theoretical task in achieving that goal is the development of the party’s general line because it is only the general line – and nothing else – which gives the party its particularity and distinguishes it from every other political force. Development of a party’s general line is primarily a theoretical undertaking because it requires the summation of broad social experience (both direct and indirect, but mostly indirect), a critique of contending lines and a projection of the strategy required to achieve political goals which are not on the immediate agenda of the working class in our country but which nevertheless fundamentally determine that agenda.

What a general line does is to set the general ideological, political and organizational orientation of the party toward the fundamental task of the period; for a party attempting to lead the working class in a capitalist society, that task is the seizure of state power. The general line embodies universal principles (such as the necessity to smash, not merely take over the bourgeois state); it embodies the basic analysis of class forces, class alliances and social contradictions, domestic and international; and it links these elements in a general strategy for the fulfillment of the party’s central task.

It is differences in the general line, rather than simply differences on a host of particular questions, that distinguish revisionism, Trotskyism and the other historic deviations from Marxism-Leninism, and it is the corruption of the general line rather than a series of particular mistakes that must be demonstrated in the full summation of a line of demarcation with consolidated opportunism of one form or another. The rectification line asserts that it is agreement around the general line – and not something else – that lays the basis for the formation of the party.

The communist movement is confronted with a variety of perspectives claiming to be correct general lines. We in the anti-revisionist, anti-“left” opportunist trend, of course, reject these claims, and emphasize that the process of developing a general line for our movement must be rooted in a thorough and relentless critique and rectification of these opportunist deviations from Marxism-Leninism.

If a genuine party existed, the task of rectification would be an activity internal to the party – but that, of course, is exactly our problem. For us, rectification must take place outside the organizational form of a party and, in fact, in order to make the re-establishment of the party possible. This is the particularity of the pre-party period, and it raises complex questions which a correct party-building line must address – questions of the proper character and role of organizational forms in this period, the relationship between rectification and re-establishment, the nature of and possibilities for verification without a party, how leadership is identified and tested, and so on. Correct answers to these questions are crucial.

Outlined in this way, our views on the central theoretical task in party building (the struggle for a correct general line) and the fundamental particularity of the period (that such work must go on outside of a recognized party) are ones which we suspect the comrades of the TR would substantially support. We have formulated the essence of this perspective more precisely as “The rectification of the general line of the U.S. communist movement and the re-establishment of its party.” With this particular formulation, however, our differences with the TR begin to open up.

Rectifying what general line?, the TR critique essentially asks, and then proceeds to offer our answer, as they see it: “We must begin rectification,” says the Club Network, “by going back to the Communist Party, USA, when it was a genuine Communist party and had a principally correct general line. That general line must be our starting point for rectification.” And, later, this is reiterated in the statement that the Clubs “premise the entire concept (of rectification) on the asserted proletarian character of the general line of the CPUSA prior to 1956.”

The significance of these views for the TR lies in the TR’s evaluation of the history of the CPUSA, which they see as having firmly abandoned a proletarian line and practice well before 1956. (The precise point at which a qualitative shift toward revisionism in the CPUSA occurred, according to the TR, is not made entirely clear.) The consequences of our error, they argue, include both an overestimation of how much we can learn positively from the CP and a consequent underestimation and narrowing of the theoretical tasks we set for ourselves.

The concern raised here by the TR is a genuine and very pressing one. As the Clubs have stated in “Developing the Subjective Factor,” “a thorough examination of the history of the CPUSA, its strengths and weaknesses, its fall into revisionism, as well as an analysis of revisionism internationally, remains a paramount theoretical task before our movement.” Such study is essential to agreement on a full summation of the line of demarcation with modern revisionism; the dangers of an incorrect approach to that task are nowhere better illustrated than in the theoretical practice of the new communist movement groups which dogmatically and uncritically rummaged around in CP history for lines to appropriate for themselves, treating it as a kind of ideological bargain basement. We recognize the fact that no force in our movement (including the TR and ourselves) has yet made the definitive case on the collapse of the CPUSA.

But even in the absence of a finished and full evaluation of CP history, several points can be made that help orient us toward that study. First, we think it is essential to reaffirm that the CP was for a considerable time the genuine embodiment of revolutionary Marxism-Leninism in the United States. We see emphasizing this point as a concrete reaffirmation of the historical demarcations with social democracy and anarchism, which deny that the CP ever had a revolutionary character. Closely related to this is our reaffirmation of the CP’s own demarcation with Trotskyism.

The position that the CPUSA was “never” a revolutionary party would certainly open up a can of worms. Given the particular history of our trend with its ideological roots in the New Left and the mass movements of the Sixties, this assessment has a profound political significance. For the critique of revisionism can provide a device for bringing the ideology of social democracy, anarchism and Trotskyism back into our movement.

Second, the history of the CP must be assessed in the context of understanding the entire international communist movement, and particularly in light of the history of the CPSU. To suggest that the period 1956-57 was a watershed is to emphasize a critical point in the history of the communist movements in most of the countries of the world, ushering in a period of splits, mass departures, and re-establishment attempts which ten years later had produced distinct “Maoist” tendencies in dozens of countries. Far-reaching criticism of the roots of revisionism internationally and in the CPUSA is essential; but the fact is that after 1956, not before, the map of the international communist movement changed decisively.

Third, and closely related, we must note that prior to 1956 the bulk of genuine Marxist-Leninists in the U.S. were contained in the ranks of the CP. Criticism of the party’s line and direction (of which there was plenty, if unsuccessful) was mainly carried on within the party, or at least oriented toward the party from outside. The genuine revolutionaries of the 1930’s, 1940’s and early 1950’s may turn out to have been wrong in their assessment that rectification of the party’s errors should be conducted within the party, but we are not prepared to dismiss that sustained collective judgment too easily.

Fourth, there is a danger in approaching the evaluation of CP history primarily through compiling a catalogue of errors. The earlier the dates at which examples can be found, the more devastating the critique appears. This approach, very common in our movement, is fundamentally ahistorlcal and relies excessively on a sometimes arrogant hindsight. Our assessment must be based on concrete examination of what problems the party was in fact trying to solve; what actual social, economic and political conditions faced the party, and how it analyzed them; and on clearly delineated criteria for what aspects of the party’s line and practice are to be primary in making a judgment of whether the party in a particular period was principally on a correct course.

We are not prepared, for example, to sum up the CP’s role in organizing the masses of industrial workers into the CIO as primarily an error, even while recognizing a consistent economist streak in the approach to that organizing. To see that work as primarily negative would require arguing for an historically possible alternative policy – in this case, presumably, some kind of dual unionism, about which we would be highly dubious.

As an even clearer example, take the Ann Arbor Collective’s analysis of the united front against fascism (in “Toward a Genuine Communist Party,” pp. 4-5). This analysis argues that certain theoretical loopholes in the 7th World Congress’s characterization of fascism (specifically, ambiguity about the extent to which sectors of the bourgeoisie could be won to the fight against fascism) allowed the Browder forces in the CPUSA to formulate their “revisionist analysis of bourgeois democracy” and implement their program of class collaboration. But what the Ann Arbor Collective does not do is assess in an overall, clearly historical way whether the conception of the united front was a principally correct line at the time and whether it correctly guided the international and U.S. communist movement in the ultimately successful struggle to defeat Hitler and his allies, preserve the existence of the Soviet Union and check extreme forms of reaction within the U.S. That assessment must be a central part of a truly materialist summation of history.

Finally, there is evidence that the TR’s perspective itself implies a troubling “narrowness” about the significance of an historical re-examination of the theory and practice of the international communist movement. This is indicated, first of all, by the TR’s assertion that we (mistakenly) emphasize the continuity, while the TR emphasizes (correctly) the discontinuity of revolutionary tradition.

To begin with, the rectification line recognizes both the continuity and discontinuity, in the U.S. and internationally. For the party-building movement, the discontinuity is apparent in our very existence as a distinct political trend; the consolidation of revisionism in the CPUSA was a fundamental rupture which obliges us to rectify the general line and re-establish the party. But to deny that we must simultaneously affirm the continuity of the struggle for a correct Marxist-Leninist orientation for U.S. revolutionaries is to suggest that we are, in essence, starting from scratch. Or, at best, that the authentic tradition runs from Marx and Engels to Lenin ... to ourselves. This kind of tunnel vision is one of the still-damaging residues of the New Left’s illusions about its own historical uniqueness.

But what are we to make of the orientation toward the revolutionary tradition implied by the following, from the TMLC’s basic party-building line statement (Party-Building Tasks in the Present Period, p. 4): “In summary, it would be accurate to say that for almost fifty years the world communist movement has operated virtually unguided with no science and philosophy capable of maintaining its revolutionary proletarian character”?

What is most striking about this sweeping statement is its patent ethnocentrism. The TR comrades may not be familiar with the theoretical work of Le Duan, the general secretary of the Vietnam Workers Party, which have added immeasurably to the body of Marxist-Leninist theory on a world scale. But they are surely familiar with the theoretical writings of Mao Tse-tung and, whatever our criticisms of the political line he developed in his later years, we would hardly deny the quality of Mao’s contributions in the realm of theory.

The fact is that the chief revolutionary impulse of the past 30 years has come out of the struggles of oppressed peoples and nations in the Third World. Those struggles have produced a significant body of collective experience which has been summed up by individuals and parties and which has profoundly guided the communist movement internationally. The historical experiences of these revolutionary struggles (and we include here the struggles in China, Vietnam, Korea, Cuba, Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, etc.) has not only been a major theoretical force in the international communist movement, it has also provided a prime material and theoretical basis for the critique of revisionism.

We agree that there has been a crisis in the development of Marxist-Leninist theory – particularly in the advanced capitalist countries. But this one-sided assessment of the development of communist theory is thoroughly idealist and magnifies the importance of theoretical work – or the lack thereof – in the west out of all proportion.

We are also uneasy with the TR’s insistence that “our starting point must always be the present state of the class struggle because it is this reality which we want to transform.” But the resources we draw on in the struggle to analyze and act on that reality are not limited to those we develop ourselves in studying “the present state of the U.S. social formation.” Nor is the present reality to be understood independently of its historical development. The perspective, as it is stated, threatens theoretical parochialism and possibly forms of “American exceptionalism.”

We have discussed these issues at some length because the TR’s view of the history of the international communist movement underlies their concern with the role of methodology and the development of advanced Marxist-Leninist concepts as the key to the successful elaboration of a general line.

“Marxism-Leninism,” the TR argues, “is a methodology and conceptual system” which has evolved through “an historical process, a process whose creative development was blocked and distorted in the 1930’s and 1940’s, a distortion out of which emerged not just Browderism and the Soviet revisionism of the Khruschev period, but Euro-Communism, and the current class collaborationist line of the Communist Party of China.” Given this legacy of both dogmatist and empiricist deformations, the TR is critical of calls for the reaffirmation of the “universal principles of Marxism-Leninism.” Unless we retrieve and reconstruct the methodology of Marxism-Leninism itself, the TR fears that appeals to “universal principles” will simply perpetuate the errors of the past.

This is the area in which we have our most important differences with the TR comrades. In our view, they make two serious errors. First, they take up only half of Marxism-Leninism as an ideology when they focus on the question of methodology. But ideology has two aspects: method and class stand. It is the latter which distinguishes Marxism-Leninism from academic Marxism, for instance. The party’s class stand is embodied in what we refer to as the “universal principles” of Marxism-Leninism. Or to put it another way: Marxism-Leninism is not just the science of society. It is scientific socialism. If the term scientific expresses the methodology of Marxism-Leninism, then socialism expresses its class stand.

To abstract one element – methodology – and to deny the existence of any “universal principles” is fatally one-sided. We believe that the TR comrades have an incomplete view of Marxism-Leninism as an ideology; or, at best, a somewhat mechanical and stageist view of how Marxist-Leninist theory is grasped.

As a result, they tend to an undialectical view of the connection between ideology and politics. Here they have something in common with the fusionists. The latter tend to the view that immersion in the class struggle will guarantee a correct ideological orientation (class stand) to the party and that this provides the foundation for forging a correct general line. The TR comrades seem to feel that putting our methodological house in order is the guarantee for developing a correct general line. Both proceed from the assumption that the ideological struggle is a separate and preliminary stage in the forging of the party and its line. But a dialectical materialist view holds that questions get settled primarily in the realm of politics, not ideology, because it is the process of trying to change the world (politics) which conditions and transforms the world outlook (ideology) of the party and the class.

As an ideology, Marxism-Leninism developed in the course of and in the service of the struggle for a correct political line.

A clear example of the approach which concerns us here comes from an article on “The Primacy of Theory and Political Line” in TR #7. The TMLC suggests that there are “two main aspects of theory, or theoretical practice: 1) the creation and refinement of the tools of theoretical analysis, the conceptual system and methodology; and 2) the creative application of these tools for the production of theoretical analyses.” The TMLC then concludes that the first aspect “must be primary in the theoretical practice of the U.S. party-building movement in the present period.” This formulation seems to suggest the delineation of three separate stages in our movement’s theoretical work: developing methodology, theoretical analysis and finally the production of actual line.

We would focus on the centrality of political line throughout the entire process, and, in fact, point to evidence that this has actually been what has propelled the party-building movement forward in recent years. It has been the critique of line, especially international line, which laid the basis for our demarcation with the class-collaborationist deviation of the “left” opportunists. Demarcations in the communist movement generally have been established over political line questions rather than the underlying ideological questions of stand and methodology. It was for this reason that we characterized the demarcation within the new communist movement as one with “left” opportunism rather than dogmatism, because it was over a political question (a class-collaborationist international line) rather than a methodological question (dogmatism) that the actual split took place. In fact, the attempt to demarcate solely on ideological grounds generally reflects a sectarian error of premature demarcation.

And it has been the struggle over party-building line which has been the basis for the methodological and theoretical breakthroughs which the rectification and primacy of theory forces have contributed in the course of the critique of the fusion line and of the Guardian staff’s party-building line. Why has this been the case? Because the process of identification and exposure of incorrect and opportunist lines emerging from within Marxism-Leninism forces the communist movement to further develop its methodological and theoretical resources to accomplish the task, much as the breakthroughs in “What Is To Be Done?” were necessitated in order to defeat the economist line theoretically and politically.

We in no way want to trivialize the TR’s concern for methodology. It is particularly important to underscore questions of method and concept formation at this point in the history of our movement’s theoretical efforts to overthrow the legacies of dogmatism and empiricism. But the first question any Marxist-Leninist must ask of any piece of history – or of any political line – is, is it correct?, not, how was it produced?

To sum up: the TR needs to further clarify its views on the relationship between the development of Marxist-Leninist methodology and the development of political line, both as a theoretical proposition and as a practical perspective on the theoretical tasks facing our movement. For our part, we believe it is the hallmark of Marxist-Leninist methodology to insist that the critique and formulation of political line be at the center of our theoretical work, and we believe that the recent history of the party-building movement demonsTRates the correctness of this perspective in life. We also hold that there are such things as “universal principles” of Marxism-Leninism, and that their concrete reaffirmation in the present context of the U.S. and international class struggle is an essential part of the rectification of the general line.

A comprehensive party-building line must take responsibility for setting the best possible conditions for the party-building movement’s successful completion of its tasks, given the particularities of a pre-party period.

The TR advances a number of sharp criticisms of the rectification line’s perspective on questions of leadership, organization, cadre development and the process of re-establishment. Despite the considerable unity we share with the TR in our common critique of the fusion line’s downplaying the role of theory, the TR echoes the sentiments of the fusion adherents (as well as the Guardian staff) when it comes to the matter of how, concretely, our movement should direct its energies. The TR repeats the charges that the Clubs’ perspective has elitist and antidemocratic implications, downplays the role of advanced organizational forms, neglects the crucial needs of cadre development and generally repeats the “familiar” errors of the New Communist Movement.

The TR is highly critical of the way in which the Clubs address questions of leadership and particularly critical of the concept of “leading individuals.” “Is this distinction between leading individuals and the movement as a whole,” they ask, “necessary and healthy? Is it a mere ideological formulation or is it indicative of a definite style of work?” Would the TR deny that distinctions can and must be drawn between the roles of leadership and the movement as a whole in the development of the general line? Can our movement afford not to wage an ideological struggle for a correct conception of leadership? Shouldn’t this conception be translated into a style of work?

In the struggle for the party (and indeed, in the party itself and in any organization built on democratic centralist principles), there is a contradiction between leadership and membership and between the development of each, and the correct handling of these contradictions is essential. To deny such a contradiction promotes ultra-democratic illusions that mask the actual assertion of leadership. And we also hold that it is the development and identification of leadership which is the decisive, primary aspect of this contradiction at this time.

The TR’s critique disclaims any view “that leadership will cease to play a critical and irreplaceable role.” We then have to ask, “What role?” Leadership must be developed, identified and tested on line, on its ability to contribute to the rectification of the general line (that is, our central theoretical task) and to the solution of the problems facing our movement – including, for example, the problems of cadre development. The insistence that leadership must be based on line – not on organizational prestige, or numbers of followers, or years of experience in the movement – is our surest safeguard against manipulation and bureaucratic centralism.

To recognize that a contradiction exists between the development of leadership and the development of cadre is also to recognize that the two are inextricably related. Cadre development can only occur in a correct fashion in conjunction with the development and practice of strong, Marxist-Leninist leadership. Cadre development in this period must also proceed on and around political line, not as some separate, “neutral” process. Cadre will be developed and trained under one or another party-building line. The principal arena of cadre development, in line with the central tasks of the period, must be theoretical development gained in the struggle to rectify the general line, although important training in other areas (organizational practice, work in the mass movements, fund-raising, publication of propaganda, etc.) will also be conducted under the overall guidance of a party-building line.

The TR claims that the rectification line is contradictory in two ways: first, it calls for the theoretical development of all cadre, while reserving “the actual production of the general political line and the party center” for a more limited number of leading individuals; and second, the emphasis on leading individuals compromises our stated determination to fight bourgeois individualism. As to the second charge, we believe that the recognition of a critical role for strong leadership sets the best conditions for the struggle against bourgeois individualism, and that it is the ultra-democratic denial of the correctness or existence of that role which perpetuates individualism.

And as for the first alleged contradiction, we repeat that the contradiction is present in reality, and not manufactured by our line. The entire rectification movement will and must participate in line development at many levels. We unite with the TR’s goal of raising the level of the entire movement to enable all the future cadre of the party to deal with theoretical and line questions at the highest possible level.

Yet the summation of the work of the rectification movement, the synthesis of this into a general line, and the advancement of this general line as the basis for concrete steps toward the actual re-establishment of the party – these tasks will not and cannot be done by “the entire movement.” Even as we encourage the widest participation and the most rapid raising of the general theoretical level, we maintain the necessary distinction between the tasks of a leading ideological center and the movement as a whole.

The TR argues that the Clubs’ “party-building plan (once the general political line has been established) is identical to that followed by the dogmatist sects.” By this charge, the TR seems to mean an assertion of leadership by a self-identified core ”divorced from a movement-wide debate in which they are responsible to collective theoretical-political practice.” We advocate no such “divorce,” since it is precisely the demonstration of leadership around line in the course of a movement-wide rectification effort which is the basis for identification of the members of a leading ideological center. The emergence of a leading core, tested in the rectification movement is the link between the distinct yet related processes of rectification and re-establishment.

It is true that the process of establishing the various “parties” which came out of the new communist movement involved the assertion of a leading center which formed the party around itself. But the error of the principal groups of the New Communist Movement did not consist in the fact that they attempted – clearly in a most distorted fashion – to assert a leading line and build from the center out. The errors were on an entirely different plane: the incorrect line around which they attempted to unify the movement. The methodological error was two-fold: flunkyism which consisted in an uncritical adoption of the views of another party; and dogmatism which consisted in the attempt to apply the universal principles of Marxism-Leninism directly to the class struggle in the U.S. without translating those principles into the necessary strategy and tactics for the U.S. revolution.

But if TR thinks that asserting a leading center based on a leading line is incorrect, the question then is, how else would the TR propose the task of re-establishment be accomplished? We know of no “strategy” or “plan” for party building, nor any instance of party building in the history of the communist movement, in which the construction of a Leninist party would proceed or has proceeded otherwise than through the assertion of a leading ideological center building “from the center out.”

The TR overlooks one significant area in which the rectification line differs sharply from the party-building strategies of the New Communist Movement groups, a critique which lays the correct basis for the understanding of organizational forms in this period. We refer here to the critique of the “pre-party formation” strategy, and the elaboration of the line on “multiplicity of organizations.”

It should be clear that the pre-party formations of the OL, the RU, etc., were actually parties in all but name; that is, there was no qualitative transformation when they proclaimed that they had fully become “parties.” These national, all-sided, democratic centralist formations were yet another example of the dogmatism with which these groups approached the particularities of party building, mechanically applying a universal principle – the Leninist conception of the party organizational form – to the distinctive work of forming a party where none exists. This dogmatism on a key organizational question was intimately related to the essentially fusion strategies of these groups, since the attempt to gain influence in the working class movement is indeed best accomplished with an all-sided democratic centralist form. This link is underscored by the fact that the PWOC is now openly committed to establishing its own national pre-party organization.

Organization must flow from, and set, the best conditions for the successful completion of specified political goals. The pre-party form, and for that matter even local all-sided democratic centralist forms, do not provide the most favorable conditions for the movement-wide ideological and theoretical struggle the rectification line envisions. Rather, Marxist-Leninists must participate in this work in the freest possible manner, unfettered by the constraints of transitory organizations which cannot command allegiance on all political questions in the way in which a party must.

We see such conscious limitations of the scope of organizational discipline as the application of a correct universal principle (that democratic centralism is the only proletarian organizational principle) in the particularities of our situation. Such a perspective provides the best conditions for maximum participation in and contribution to theoretical work and line struggle; it provides the best basis for the emergence of leadership which is clearly based on line, not organizational representation; it maximizes interaction among Marxist-Leninists; it helps safeguard against the dangers of building factionalism into the party when it is re-established; it combats tendencies toward careerism and hegemonism; and it emphasizes the necessity for all Marxist-Leninists (not just leadership) to be accountable for their views as individuals. This last is essential if the re-establishment process is to proceed correctly; membership in the future party cannot be simply a matter of someone saying, “Sign me up,” or of automatic membership based on a prior affiliation, or of a certain number of years of activity in the movement.

This does not mean that organization plays no role in this period, nor that organizational forms should be constructed in an ultra-democratic fashion; nor is it a concession to the Euro-communist and social-democratic attacks on the Leninist conception of the party, nor a loophole for the re-emergence of localism in our movement – all possible implications raised by the TR. The organizational practice of the Clubs and other initiatives guided and encouraged by forces upholding the rectification line should refute these fears. The Clubs, for example, are certainly national in form, and do uphold democratic centralism around their basis of unity – principally, party-building line and the lines of demarcation with revisionism and “left” opportunism – while encouraging members to participate in rectification work as individuals.

In order to accomplish the wide variety of particular tasks that contribute to a rectification movement and to the goal of rectification of the general line, a multiplicity of different organizational forms is called for, forms suited to the particular political tasks they address. The forms suited to national communist intervention in the anti-racist struggle will, of course, not necessarily be the same as forms appropriate to study of particular line questions or forms appropriate to the systematization of struggle over party-building line.

Finally, the TR raises objections to the concept of the multiplicity of organizations because it seems to resemble the “extreme specialization and increased division of labor (which) are characteristics of advanced capitalism.”

Beneath the hyperbole, the legitimate concern raised here is the danger of one-sided development and the need to develop both the leadership and cadre of the party with the broadest vision and theoretical capacity possible. We certainly unite with this goal, but believe, in fact, that organizational differentiation is necessary to its actual accomplishment. All-sided development need not and cannot be the product of direct experience in every area of work – neither in a party nor in a pre-party period. It is the collective summation of the most advanced lines and experiences, taken up in a synthesized form by the movement as a whole, which best raises the actual level of the whole movement all-sidedly. The multiplicity of organizations also carries no implications that cadre are limited to participating in one and only one – that is more clearly the perspective of those who seek to construct all-sided organizations at this time.

To sum up: although the TR has clearly broken with the fusion line on the nature and centrality of theoretical tasks in party building, the TR has not yet drawn out the implications for other aspects of party-building line. Questions of leadership, organization, cadre development and re-establishment are at the heart of any conception of how to build a party and whether that party will have a truly Leninist character. If we are to take responsibility for altering the conditions of backwardness in our movement, for changing the form of relations among communists, for making the rectification of the general line and the re-establishment of the party a practical task, not just a theoretical concern, struggle around these questions must proceed with the utmost urgency.

All of which brings us quite logically to our final point: the differences between the Clubs and the TR forces on the question of affiliation with the OCIC.

We hold that at this time the central struggle within our trend should be and is the struggle over party-building line and strategic orientation for our movement, and that the question of whether forces do or do not join a particular organization is therefore a secondary matter. But leading forces in the OC, and especially the OC Steering Committee, have succeeded in some measure in persuading large sectors of our movement that agreement with “the OC process” is the central question, and the test of good faith of all Marxist-Leninists. This has served to mystify the line struggle and substitute the appearance of an organizational struggle – the OC vs. the Clubs, rather than fusion vs. rectification.

As anyone who reads past statements by the TR/TMLC/Ann Arbor/Red Boston Collective forces knows, the adherents of the “primacy of theory” line have advanced for years a substantial critique of the approach embodied in the OCIC. This line of critique has emphasized that fundamental differences on party-building line existed in our movement, and that the resolution of these differences was a precondition for a truly leading center. We unite with the perspective advanced most recently in this statement from TR #12:

The real question is not ’do we all want unity?’ but, ’on what basis will the anti-dogmatist, anti-revisionist communist movement be unified?’

The TR, of course, also has a sharp critique of the fusion line, and readily admits that fusion forces and, more important, the fusion line is the dominant line within the OC, even if it is not a formal point of unity. In short, the TR has made a case that the theoretical underpinnings of the OC strategy are, at best, shaky. One major difference between our perspective and that of the TR is that we stress the connection between the faulty conceptions of the OC itself and the faulty conceptions of the fusion line which leads the OC, and the fact that the TR does not make its case in this organic way is, we think, related to the TR’s tendency to downplay the decisiveness of political line, a point elaborated earlier.

The TR advances two essentially tactical reasons for why they have joined the OC, which are also advanced as criticisms of us for not joining. The TR holds that the plans for the OC’s development must be seen as “fluid rather than static, developing rather than pre-determined”; and it asserts that, therefore, the majority of forces in the party-building movement “will view as premature and sectarian the Network’s decision not to first try and struggle for the rectification line within the Organizing Committee.”

It is striking that the TR would rest its case on what “many forces continue to believe,” and not on the TR’s own theoretical demonstration of the correctness or incorrectness of the OC strategy. This evades the TR’s responsibility to clarify its own views. Particularly when the OC increasingly puts itself forward not just as “a center” but as “the center,” comrades in our movement have a responsibility to strive for the utmost clarity on these questions.

The assessment of whether the OC is “fluid rather than static” cannot be left to the OC’s own self-descriptions of its openness; it must be based on drawing out the full implications of positions taken by the OC and its practice around them.

We would highlight briefly three developments and ask the TR to offer its own views on these questions.

First, the OC’s increasing consolidation around an incorrect view of the line of demarcation with “left” opportunism. The overwhelming majority of forces in the OC endorse the mistaken view that we are all still part of a “single anti-revisionist movement” which also includes the forces holding to some variant of the notorious three worlds theory. The TR disagrees with this refusal to recognize an objective demarcation, as do we. It is also clear that the “OC process” around point 18 has resulted in an organizational break with forces under the influence of this class-collaborationist international line, yet not a political break. The fusion forces are the leading (perhaps only) forces within our trend who cling to this “single movement” perspective, and their main allies (in terms of line) are the forces outside our trend (the Proletarian Unity League, Boston Party-Building Organization, and so on) who have consistently practiced questions of party-building line: the OC is now proceeding to adopt portions of the fusion line one at a time, while calling these debates something else.

Second we must assess that the OC has not made significant progress toward actually “organizing and systematizing” the ideological and political struggle. It has not, and does not propose to, take up party-building line for some time. It has produced very little in the way of original and advanced theoretical work. It has taken only very limited steps toward the goal of raising the theoretical level of our movement, training cadre theoretically, or encouraging the attention to scientific methodology the TR emphasizes so strongly. It has, in fact, set our movement back in its consolidation of advanced views on certain questions, notably the lines of demarcation and party-building line. More particularly, as evidenced by the rampant commandism and demagogy at the OC national conference in Chicago, the OC leadership is training its cadre in a thoroughly non-Leninist fashion and subverting their ability to take up the tasks before us.

Finally, the OC has launched a nationwide sectarian attack on the Clubs and other forces holding the rectification line. The Clubs have been portrayed as merely proponents of “circle warfare,” as the new carriers of the “ultra-’left’ line,” as proof of the continued hegemony of “left” ideas in our trend; as opposed to any “common work,” and so on. The point is not the alleged validity of these views, which we certainly reject. The point is, rather, that the OC has moved to defeat a party-building line without discussing it, studying it, and engaging in debate with rectification forces over our differences; it is once again an organizational solution to a political problem. Even forces who hold that the rectification line is incorrect cannot have much confidence in the kind of “leading ideological center” which would be built on demagogy, not rigorous struggle.

Those who oppose an incorrect line are not responsible for sectarian attacks launched in defense of it. It is the fusion line which is dangerously incorrect; it is the fusion line which guides and is increasingly expressed in the OC’s sectarian deviation, headquartered in the OC steering committee and in the PWOC. For the Clubs to advance a critique of the fusion line and of the OC is not sectarian; it is an invitation to an open struggle around the fundamental line which will guide all the work of the party-building movement and determine, for good or ill, the future character of the party.

OC forces have adopted the policy of consciously boycotting initiatives undertaken by rectification forces, excluding us from initiatives they undertake (such as the conference of minority Marxist-Leninists). The tendencies towards caricature and demagogy have been stepped up. All the signs point to the inescapable conclusion that the leading OC forces have made a conscious decision to read the NNMLC and the rectification line out of our trend.

We point this out not to underplay the significance of the differences between us but rather to remind us of the common stake we have in combatting the present drift in our trend. At the same time, we must face up to the possibility that the OC leadership will not be diverted from their reckless course, making the tasks of rectification and re-establishment that much more difficult.

For our part, we believe it essential to continue the struggle over party-building line while simultaneously advancing the theoretical work required for line rectification. To this end we have helped launch a number of initiatives And urge other comrades and organizations to do the same.

In particular, we look forward to further struggle and common work with the TR and the forces under the guidance of its line. If the present exchange of views leaves many questions unsettled, it has at least laid the basis for taking the debate to a higher level. And we hope it has also helped to demonstrate that the resolute struggle over “shades of difference” is not a threat to our movement, but rather the vehicle for propelling it forward.