First Published: Forward, Vol. 7, No. 1, January 1987.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

What is happening with the working class in the U.S. today? How can labor improve its situation? And what about socialism and the labor movement? These are some of the issues Roberto Flores addresses in this interview conducted by Forward in Los Angeles in December 1986.

Roberto Flores has been a member of the United Steelworkers union (USWA) for seven years. He was also a vice president of a local of the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers union. His parents were field and industrial workers and ran a small restaurant in the farm worker community of Oxnard, California. Roberto was one of 14 children. A farm worker himself for many years, he was a leader in the 1975 strawberry workers’ strike in Oxnard and a member of the United Farm Workers Union (UFW). He is married and has six children.

What is your opinion of the present state of the labor movement?

The labor movement is facing a difficult and challenging situation. There have been many changes in the U.S. politically and economically, and the labor movement has to adjust with new approaches. The U.S. economy is very different today from what it was in the 1950s and 1960s, from being the most powerful economy in the world to one facing increasing problems. It is losing markets to foreign competitors, the military budget is devouring resources, the national debt keeps soaring, unemployment remains high, the farm sector is depressed, productivity is declining, and fears of a major banking and stock market disaster continue.

I don’t think the U.S. economy will ever regain its top position in the world. The ability of U.S. corporations to dominate world markets, take natural resources cheaply from third world countries and reap incredible superprofits has been seriously damaged. To keep up profits, the capitalists are viciously attacking the wages and the working and living conditions of the working class.

The social structure has also changed. The working class in the U.S. is increasingly polarized, with a small group of unionized and relatively high-paid workers on one end and the overwhelming majority of workers with low-paying, low-security and mainly non-unionized jobs on the other.

The labor movement has to confront the changing situation and develop more coherent and sharper strategies to fight these attacks. When Reagan signaled that he would openly side with big business and smashed the air traffic controllers’ strike in the early days of his first administration, the labor movement was unprepared to deal with the offensive. This continued through the first half of the 1980s. Labor was off-balance and unable to mount an effective counterattack. Other major strikes, such as by the Greyhound, Continental, and Phelps-Dodge mine workers, among others, suffered defeats. Everywhere labor was assaulted with employer demands for concessions and “takeaways.”

The offensive on labor is continuing, but recently I think there are signs that some sectors of labor are beginning to rally a more effective fight. The Farm Labor Organizing Committee won a contract from Campbell in Ohio, and the Farm Workers Organizing Committee (Comite Organizador de Trabajadores Agricolas – COTA) won contracts in New Jersey. The hotel and restaurant workers won big victories in Las Vegas, Boston and San Francisco. Unionization drives were successful at Yale and Columbia. Delta Catfish workers in Mississippi won an NLRB election and are fighting for a contract now in a major victory for the “right-to work” South. And Chinese garment workers won a precedent-setting settlement on a plant-closing issue in Boston.

The Hormel workers in Austin, Minnesota, continue to fight to win their jobs. UAW workers at Delco won their recent strike, showing that even GM is not invincible when confronted with a strike which threatens to shut down all their plants. The Watsonville cannery workers are still striking after 15 months, and a victory still appears possible. The steel workers out against USX seem to be prepared to weather a long battle. This is the first time in many years that the United Steelworkers has decided to fight it out with the big steel companies.

These successes have some common ingredients which may give us some insight on organizing in this period. They are generally characterized by a more vigorous approach by the unions, active support from the community, especially from oppressed nationality movements, and strong rank and file participation, unity and militancy.

More workers are recognizing that concessions have not stopped layoffs and cuts of wages and benefits. It is also becoming clear that despite a better situation for big business, employers are still viciously attacking workers. I think more and more workers have just had enough and can see more ways to fight, all of which has stimulated a greater fighting spirit and resistance among workers.

What about the attitude of the top labor leaders now? What is going on with them? Are they taking up the fight against the right?

Most of the top labor leaders did not play a good role in the early 1980s when workers tried to resist the employer offensive. They not only didn’t resist but pressured workers into concessions and surrendering to Reagan. This is what Douglas Fraser of the UAW did, for example. Jackie Presser of the Teamsters, of course, openly backed Reagan.

But I think that even some top leaders are now seeing that they better do something or else their unions are going to get completely squashed. It is pretty obvious that big business in many cases is out not just to reduce the power of labor, but in many cases eliminate some unions altogether. It’s been made clear there isn’t any room for labor in Reagan’s USA. The international unions are also facing a lot of pressure from the locals and the rank and file.

For example, top leadership of the Teamsters Union has backed up the Watsonville strike. Not in the complete way they should, of course, but more than they have supported other strikes for a long time. The national leadership of the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union in the Boston and San Francisco strikes also showed vigor and openness to innovation.

Of course, many top AFL-CIO leaders continue to cave in to employer demands for concessions and oppose the rank and file. They’re obstructing progress in the labor movement. The main thrust for any change in the unions must continue to come from the rank and file.

Top labor leaders have gotten where they are by being better representatives of the company than of the union’s members. But at present, with the onslaught of the right, even some leaders are finding that they have to wage more struggle with the employers. When that happens, workers can use it to their advantage.

It’s interesting how this question is viewed on the left. One school of thought sees a united labor movement as the workers’ first line of defense against the capitalists and holds that to criticize unions or attack their leaders, especially at a time like this, is divisive, irresponsible and plays into the enemy’s hands. Those who uphold this view point out that even under left leadership it would be very hard for unions to win gains today, and we shouldn’t take “cheap shots” at union leaders who have failed to do so unless we have concrete strategies of how we could do the work better.

The other tendency attributes the current weakness of the labor movement in large part to a corrupt, bureaucratic leadership which has abandoned the ideals of militant, democratic trade unionism. It places a big emphasis on encouraging rank and file union members to challenge the actions of their leaders.

I think there are merits and shortcomings to both positions. As for the first, I agree that we must take responsibility for the overall welfare of the union movement and assess each struggle’s chances for victory with a realistic attitude before embarking on different courses of action, especially strikes. However, it is foolish and dangerous to ignore the contradictions between top union officials and rank and file workers. The actions of the United Food and Commercial Workers union leadership in the Hormel strike show all too clearly how serious these contradictions can become. In situations like this, the left has a responsibility to face the situation squarely and come down firmly on the side of the workers.

On the other hand, workers are obviously stronger when they are able to work with their union officials than when they must fight the union and the company at the same time, as the Hormel workers were forced to do. It is foolish to not work with the international when it is at all possible. This does not mean of course that the workers must give up any initiative while forging this united front with top officials.

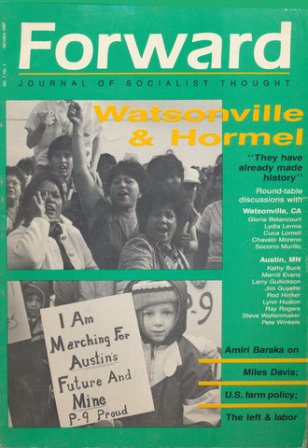

What do you think is the significance of the Watsonville and Hormel struggles?

Both the Watsonville and Hormel struggles have inspired the labor movement with their militancy, determination and political consciousness. The workers have faced hundreds of arrests, beatings and other tremendous obstacles. But still they fight on. The strikes are among the leading labor struggles in the U.S. today.

The Watsonville workers, who are mainly women and Mexicanas, have been out for a year and a half with not one worker scabbing. This is a remarkable testimony to their organization and determination. The Watsonville strikers are united and have maintained some level of initiative in their long struggle. They elected their own strike committee, forced recognition of this committee from the union and managed, despite some differences with their local union leadership at times, to forge a united effort with them, and with the Teamsters International.

The Watsonville strikers also see their struggle within the context of the struggle of the Chicano and Mexicano people in the U.S. for basic democracy. They understand that their battle for a decent wage and union representation will affect the lives of over 50,000 Chicano/Mexicano cannery workers throughout the valleys of California and will have a huge impact on the future of all Chicanos. They know and have expressed eloquently their understanding that becoming cannery workers is the first step out of the fields, enabling their children to attend school more regularly and improving their lives. Because of this the Watsonville strikers have reached out broadly into the Chicano Movement, drawing emotional and economic support and especially political support to them. This attention and concern by almost every elected Chicano/Mexicano politician in California for the outcome of the Watsonville strike has been an important additional pressure on the company and the Teamsters International.

This strike contains powerful lessons which the labor movement must recognize if it is to revitalize itself.

The Hormel strike is significant because for many workers it represented “drawing the line” against the bosses. The Hormel workers said you are not going to bleed another drop out of us. We are going to fight, even if the International is not going to support us. They captured the spirit and feelings of millions of workers throughout the U.S. Even though the AFL-CIO and UFCW leadership refused to support the strike hundreds of locals and tens of thousands of ordinary workers supported P-9. The Hormel workers are a great inspiration to workers throughout the country.

The strike is also significant because of the democratic way it was conducted. The rank and file was involved in all the major decisions of the strike. The struggle showed the capability of the rank and file worker and the power of union democracy. I think this is something many other workers will learn from.

The Hormel workers also linked their struggle with the broader movement for progress and justice in the world. Their dedication of the mural on their union hall to South African freedom fighter Nelson Mandela is an outstanding example of this. You have to remember that P-9 is mainly white. At a time when the racists and fascists are trying to win over white workers, the stand of the Hormel workers against apartheid and in support of Native Americans, the Watsonville workers, and many others, is a strong reminder of the unity which the working class can achieve in the common struggle for a decent life.

What are the tasks of left forces in the labor movement at this time?

The left has the responsibility to try to present its ideas for how the working class can turn back employer attacks and gain some initiative on a national scale to fight to preserve the unions and to improve the lives of the majority of people in this country, who are workers. In our view the key thing which the labor movement must realize is that there is a powerful movement for democracy in this country, in particular by the African American and Chicano/Mexicano/Latino peoples. This struggle for democracy, centered primarily in the South and Southwest, has the potential to turn those areas, which are bastions of right-to-work laws, weak unions and conservative government, into progressive regions which can turn back the right-wing tide and bring a more progressive agenda onto the national political arena.

The left should encourage more active and independent participation by the labor movement in the political arena. We should help mobilize the workers and the unions to become the foremost champions of democracy. The labor movement should be known as a fighter for minority empowerment, immigrant rights and progressive foreign policy issues, such as opposition to U.S. policy in South Africa and Central America. We need to do much more extensive voter registration and education.

We want the unions to fight for such things as raising corporate taxes, cutting the military budget, creation of a national jobs program through the reconstruction of the nation’s basic infrastructure – roads, bridges, dams, schools, increasing the minimum wage, etc. Given the economic direction of the country, labor will inevitably interject its own agenda into the political debate, and it is vital that the left participate in forming this agenda so that labor will not get swept into a demagogic direction.

The left has a special responsibility to organize, activate and develop the leadership of the workers themselves in this struggle. The left must help to build a strong, unified and militant and mass-based labor movement. We have to encourage and support workers in their struggle and help them organize. The working class movement will be as strong as the ability of the workers themselves to grapple with the problems of developing the right tactics, finding allies, knowing when to go forward and when to retreat, building multinational unity, and so on.

The League has put forth for some time the importance of the lower stratum of the working class for the future of the labor movement. Can you elaborate on that?

We see the lower stratum of the working class playing a critical role in building the labor movement. By lower stratum, I am referring to low-paid, unskilled production workers in basic industry, manufacturing, service and agriculture. These workers are relatively more oppressed and, in many instances, suffer national and women’s oppression as well. They are also, relatively speaking, less influenced by the corrupted labor leaders and are more open to progressive and socialist ideas.

Over the last few years there has been a whole rash of struggles, many of them unpublicized, by oppressed nationality lower stratum workers. In many instances, they have come up against a powerful array of opponents – hard-line employers, the state, and non-supportive union leaders. Yet these have been some of the most militant and vibrant struggles in the labor movement. It is not an accident that most of the organizing and contract victories in the labor movement in this past period have been among these workers.

In many cases these struggles of the lower stratum workers have combined a fight for better wages, unionization and working conditions with demands for an end to racial and national discrimination and inequality. They have also often been in the South and Southwest, which as I mentioned earlier is not a coincidence and further demonstrates the significance of this sector of the working class on the future of this country.

The connection of oppressed nationality workers to the struggle for political empowerment and basic democracy is a powerful source of strength for the entire labor movement. The failure of organized labor to deal with the national question, and the issue of thoroughgoing democracy in general, remains the single greatest obstacle to its progress. Labor is going to have to end its exclusion, even opposition, to the demands of workers traditionally excluded from labor, such as minority workers and women workers.

You mentioned the need for workers to get active in the political arena. Why is this important, and how should the labor movement relate to such things as the likely presidential bid by Jesse Jackson?

The labor movement must fight in the political arena because so much of what goes on there affects their interests. Union-busting got its biggest impetus when Ronald Reagan and a Republican Senate were elected into office in 1980. Workers cannot protect their basic interests by focusing exclusively on labor-management contract struggles.

At the same time, the labor movement should not simply rely on the mainstream of the Democratic Party. Look what happened in 1984 when the AFL-CIO handed Mondale a blank check. This strategy backfired horribly. Its impact was largely negative: it was unable to rally workers behind Mondale, and it also made it virtually impossible for other candidates like Jesse Jackson, who represented workers’ interests and aspirations far better, to get union support.

The formal labor component of Jackson’s support was minimal in 1984. Only a handful of union locals actually endorsed Jackson, despite the fact that thousands of workers, and many local union leaders, were not only open to Jackson’s message, but were enthusiastically supporting it. However, a possible Jackson candidacy offers the labor movement a great opportunity. He has a strong progressive platform and has actively supported labor struggles such as the Hormel and Watsonville strikes, and others. His movement is a genuine mass movement and the most progressive and consistently pro-labor in the country.

In the last year, Jackson has been talking to national labor leaders such as Kenneth Blaylock of the American Federation of Government Employees, Lynn Williams of the Steelworkers, Richard Trumka of the United Mine Workers, and William Winpisinger of the Machinists. We should do all we can to encourage this dialogue and for the unions to support Jackson. As in 1984, the Jackson campaign will be the main mass electoral challenge to the right. It will be the main mass electoral vehicle for building multinational unity and for asserting a progressive political platform. Jackson’s campaign will force the Democratic Party to address issues important to labor and the minority communities and will help combat the right.

At this point, no candidate has emerged whom organized labor is courting. Democratic I candidates may not even want an early endorsement, lest they be labeled as beholden to “special interests.” The AFL-CIO would do best to refrain from handpicking labor’s candidate and allow workers and unions on the local, regional and international level to support whom they please. As for the left, it should strengthen the Rainbow Coalition within the labor movement as part of the fight against the right.

Many on the left seem to have given up on the possibility of socialism ever being a mass movement and mass force in this country. What is the League’s view on this matter?

Well, I’m a communist, I believe in building for a socialist society. I think a socialist U.S. will be more just and fair for the majority of the people. I know that a broad, mass socialist movement can be built. I know that a majority of the people in this country are potentially open to and can become socialists. If you think most people in the U.S. will never support it, there is no point in believing in socialism.

I believe this because of my own personal experience but also because I know there are certain contradictions in this society which can’t be resolved under capitalism. The U.S. and other advanced capitalist countries can’t survive with a system which has such a few people controlling the wealth and the fields and the factories but relies on the broad majority, who have very little control or share in the wealth, to actually carry out the work. Right now many working people in this country are being forced into poverty, and the quality of life for all working people is deteriorating.

People will not suffer continuously without struggling for a better life. I think socialism represents that.

Most of my family have worked in the fields, packing sheds and factories of California. What we’ve been through is what millions of families in this country go through. When I learned about socialism, I knew that this is the direction society needs to move towards. The common experience of growing up as working class Chicanos/Mexicanos is leading other members of my family to the same conclusions as well.

Some people on the left seem surprised when mass leaders and regular working people come out in support of socialist ideas. Recently, I was at a Unity newspaper program of several hundred people, with workers from Watsonville, janitors from Local 77 in San Jose and Commercial Club strikers from San Francisco. Many of these workers talked openly about the need for socialism and about capitalism as the source of their suffering. Last winter a Watsonville striker addressed a large labor gathering in New York and surprised many people by endorsing socialism herself and targeting the capitalist system. I’ve had this same experience in community and student work as well. In struggles around migra attacks, for bilingual education and the broader issue of educational rights – in all the thousands of ways that people struggle against their oppression in this society – I have found that people actively trying to change things are open to socialist ideas. After all, I became a socialist through a similar process.

There are many on the left today who are concerned about the relevancy of the left and are working very hard to gain more influence for themselves or their organizations in the mass movements, and in policy debates. That’s fine, but we in the League believe that the left in this country will never become more relevant unless there is a mass socialist movement, until a sizable portion of the masses of people in this country consider themselves “of the left.” We have tried to devote attention to this question: how do we win over more people to socialism?

We know this is difficult to do. There is a lot of anti-communism in this society, and being open about your ideas can lead to redbaiting. Nevertheless, we feel that we must be open about our ideas and what we believe in. Otherwise, how can people ever become acquainted with socialism and with socialists beyond all the anti-communism they hear all the time?

In my own experience and the experience of other people in the League, we feel that we have been able to break down people’s misconceptions about leftists by showing in practice, in real life, that we socialists are the most dedicated fighters for people’s interests. I believe that in the course of fighting every instance of injustice, many people will learn from their own experience that socialism is not only desirable but necessary.