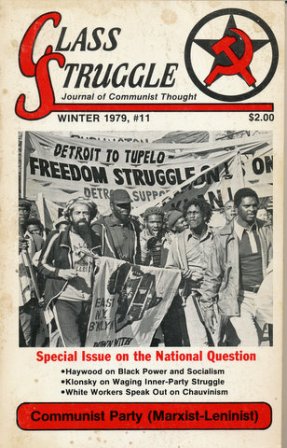

First Published: Class Struggle, No. 11, Winter 1979.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The U.S. working class is made up of several nationalities. This point is readily apparent to anyone who has examined the work force in the big factories in most major U.S. cities. But it is also apparent that the U.S. bourgeoisie has had considerable success in dividing this class against itself, especially through the use of white chauvinism. Since the vast majority of the U.S. proletariat are white workers, the role they will play in fighting for unity is one of crucial importance to the struggle for socialism.

Since the rise of imperialism, there have been two great revolutionary movements in American political life–the general workers’ movement and the struggles of the oppressed nationalities, especially the Afro-American peoples movement. Both together and separately, they have persistently fought the exploitation and oppression of the capitalist system.

To the degree that these two forces have been united, both have been able to register their greatest gains in the struggle against capital. This was especially true in the 1930s, which saw worldwide struggle to free the Scottsboro Boys and organization of the CIO. But when they have been divided, both movements have suffered defeats and reversals.

Only the bourgeoisie profits from the system of national inequality and divisions among the people. In fact, it has cost the proletariat everything, especially the birthright of the working class, the prospect of socialism and a future free from exploitation. Particularly in times of crisis, the capitalists will go all out to intensify these divisions as a kind of “insurance” against revolutionary challenges to its continued rule.

Today’s crisis confronts us with a difficult task in this regard. From the resurgence of groups like the Ku Klux Klan to the more subtle racist ploys of the liberal politicians and trade union bureaucrats, the unity of the working class and the people’s movements are again under heavy fire. This has been further complicated by the revisionist betrayal of the old CPUS A in the 1950s, which left the working class without revolutionary leadership. The workers were thus disarmed in fighting the white chauvinist propaganda based in the labor aristocracy and promoted by the labor bureaucrats.

Under these conditions, what is the best approach for revolutionaries to take to the white workers? What has been the impact of the Black liberation struggle on the thinking of the white workers? What struggles in their experience have provided the best lessons for learning how to promote genuine, class-conscious unity among the peoples of different nationalities?

To get some answers to these questions, Class Struggle has gone to the white workers and activists themselves. We talked to dozens of people in two cities, Boston and Atlanta. Boston was picked as a Northern industrial center which has gone through a major battle over segregation in the schools. And Atlanta was picked in order to focus on the situation of white workers in the South. We also talked with people in a wide range of social situations–workers in heavy industry, in service industry, unemployed workers, housewives and welfare mothers, men and women, and young, middle-aged and older workers. Some of these were communists with many years of experience, others were militant class fighters only recently involved in the struggle.

The interviews thoroughly refute the myth that the masses of white workers are “bought off” by the capitalist system or that they are “inherently” chauvinist. In their own words, these activists explain how white workers can and will support the struggles of the oppressed nationalities as they come to understand how it is in their own class interests to do so. They explain how they were won to the struggle themselves and what methods they use in winning over other white workers. While the interviews are not meant to be a complete or comprehensive discussion of this subject, they are a good beginning and provide many useful lessons for organizers. The interviews were done for Class Struggle by Margie Winbourne, a leading CPML activist from Boston.

* * *

This first interview is with Bob and Dianne, two members of the Southern Conference Educational Fund (SCEF) who grew up in the South. Bob comes from a small Georgia town. His father was once a member of the old CPUSA, but left when it was taken over by the revisionists. He had always told his son to seek out people carrying on the fight against the capitalists. Dianne is also from a working class background.

The interview begins with a detailed account of the Bennie McQurter case, a movement that grew out of a police killing of a white unemployed youth. Since most of the people we talked to in Atlanta referred to this case, which saw many breakthroughs in organizing white workers, it is recounted here for readers who may not be familiar with it. SCEF is a fighting people’s organization in the South, with chapters in eight states. It is an affiliate of the National Fight Back Organization.

Tell us a little about your background and how you got into the struggle.

Dianne: I was brought up in a working class, Southern Baptist family with a lot of racist propaganda. I was always told, “If you work hard, you’re going to make it.” But as I talked with other people, began to read stuff and to listen, I began to see how all my problems, all of the social ills we face, were linked back to the system. I saw that we all had a common enemy. That’s when I wanted to get involved.

You were active in the Bennie McQurter case. Could you tell us about the case and how you organized in his neighborhood?

Dianne: Bennie McQurter was a young, unemployed white worker. Because he was unemployed, the only thing he used to do is look for a job and go to this little bar near where he lived. The bartender didn’t want him to sit in there all day and drink one beer, so they ran him out and called the cops on him. Well, they told the cops where to find him–he was walking home just two blocks away. A cop car with two policemen came up and harassed him. They asked him his name and said that they had identified him as another person.

Bob: They picked Bennie up and brought him to his parents’ house and asked, “Do you know who this is?” His father said, “Yes, that’s my son Bennie McQurter.” Then they took him down the street. When they got there, he kicked out the window in the back seat with his feet. He was barefoot and his feet were cuffed. His hands were cuffed, too, behind his back.

When he kicked it out, his family saw and started running down the street. The cops pulled him out through the broken window. One cop started beating on him. Then the other cop got him down on his back and put a flashlight at his throat. He put one end of the flashlight in the inset of his elbow and got the other end in his hand and just pulled it back, choking him. They held him that way for a long time. All this while his friends and neighbors were telling the cops to quit beating him. He was just laying limp.

By this time, other cops had arrived, pushing people back. They threw Bennie in the paddy wagon and took him down to book him at the police station. He was probably dead by that time. Then they took him to Grady Hospital. When they brought him out of the police station, they had him handcuffed to a wheel chair and his head was laying down. He was dead then, but they were pretending like he wasn’t.

Dianne: When we found out about it, the first thing we did was call a community meeting. We went door to door in work teams of about eight people. We divided up the streets. We had leaflets asking people to come to a meeting. We told them about the incident. Of course, it wasn’t in the papers or anything at first. We also started a petition campaign. We went door to door for about a week. We would meet, then go out on the work team, then come back and talk about the questions people asked and how we could answer some of the questions on the minds of the community the next day. We had a couple of big memorial meetings. The big “city fathers” thought it was really important because all these people were getting out onto the streets. So they came to say that everything was fine and of course the police would investigate themselves and justice would be done.

Most people didn’t have any illusions. It became clear over the course of our work that the police were not going to do anything, that this had happened many, many times. Because every time we went to talk to somebody about this, they said, “Well, I know another case of police harassment”–people actually being killed at the hands of the police. We found that a lot of people in the community didn’t have jobs and were subjected to searches and all kinds of illegal harassment. Girls in the neighborhood were always being propositioned by the police.

Bob: When the police commissioner came out, some people fell for it. They thought this authority was going to handle it all, make everything right. One of the main things we had to point out was that they weren’t going to do anything but let the cops go who killed Bennie McQurter. We kept pointing this out. Finally, when it became came obvious that the cops weren’t going to be prosecuted, people started really believing us a lot more.

Dianne: The people really learned from their own experiences during the trial. You could really see it. They even went so far as to have bogus witnesses.

Bob: The cops only really had one witness. He was an alcoholic who never had anything. Within a few days after Bennie was killed, he had a brand new pick-up truck and plenty of spending money. So evidently, they bought him off. His testimony couldn’t even compare to all the people who testified against the cops.

Dianne: So we had a mock trial where we prosecuted the police and the people from the community really enjoyed that. You could tell that they really learned a lot of lessons from that struggle because of the way they portrayed the people. We had the weasel, which was the bogus witness. We sentenced the cops for murder. One of the SCEF members played the police commissioner and showed how he was bought off by the business community. It was well attended.

Bob: An interesting aspect of the case came up because the police commissioner was Black. So even though the cops who killed Bennie were white, it was going to be a Black man who let them go. This gave us a good opportunity to fight against racism because we could point out right from the start that it was the system itself that was the problem.

Dianne: We showed the Gary Tyler film at an outdoor rally. A lot of the white workers really saw the parallels between his case and the case of Bennie McQurter. People saw that there was some unity there because poor whites and Black people had both got rotten treatment from the police.

The struggle about Bennie McQurter really interested them in other cases. The cops were reprimanded by the city only for having killed Bennie with a flashlight that was not a regulation flashlight. It was their own flashlight.

In general, what lessons have you drawn from working among white workers in the South?

Dianne: The main thing is that in the South the standard of living is down for everyone because there is an oppressed Black nation. That’s how to win white workers over–for them to realize that because Black people make less, the wages of white workers are brought down, too.

White workers have misconceptions about Black people, especially if they grew up in a city where segregation was really prevalent. But one thing that became very clear to me when I started working in a factory with Black people is that you’re all oppressed by the company, by the capitalists. It’s easy to talk to white workers about how they’re making money for someone else and that Black workers are in the same situation.

Bob: One thing we have to take into account is that there are cultural differences between Blacks and whites. On the other hand, in a lot of ways poor white sharecroppers and Black sharecroppers have much more in common than poor whites and rich whites. Most white people don’t know much about Black history. You have to have a protracted view to show them the history of Black people.

Dianne: Black people worked the land down South and they have a right to that land. They gave their blood and their lives to make somebody rich. Black people have been denied political power and have the right to it. I think white workers can understand that.

One last thing: I think it’s important to understand that even though we don’t support racism, we’re still influenced by it. The ruling class has many ways to get their ideas across. Even after you see the need for unity, it’s still a struggle.

This interview is with Barbara, a white activist involved in the South since the early 1960s. She got into the civil rights movement as a young student and was initially motivated, as she put it, “by a lot of liberal moralism.” She has been a factory worker for several years now, but the conflicts and changes in her viewpoint are instructive for many young students and progressive intellectuals today.

You have been an activist in the South for a long time, since the early 1960s. How have your views on white workers and the national question changed over the years?

Barbara: As I got involved, I went through different levels of understanding about the white workers. There was a lot of struggle in the 1960s in the student movement and in the Black movement about what role whites and, in particular, the white workers had to play. As a white Southerner who got very deeply involved in the civil rights movement, my earliest views were of whites as racists and as completely bought off. I saw no potential for allies there. I thought that the Black liberation movement didn’t have any allies among the white workers. I didn’t like being white myself. I was very young at the time, about 19.

I worked in different project offices and activities in Virginia and Mississippi. These were targets of the Klan, and there were a lot of run-ins with the Klan, cross-burnings and that kind of stuff.

The conclusions I drew then were wrong and real sectarian towards white workers. Fortunately for my development, in 1967 1 did some work with the textile workers’ union in North Carolina. We were in a strike situation and I met a lot of older white workers who had helped to build the unions in the 1930s. Then I began to think differently about the role of whites in the class struggle. I didn’t have an understanding about the class struggle when I first got involved in the civil rights movement. I didn’t see it as a class question.

But doing labor work helped change my views. The line of the union was just “Black and white, unite to fight.” They didn’t take up the special demands of the Black workers, but just tried to start on the basis that we should all get together and build a union because conditions were bad. But even with that kind of leadership, I began to see the potential for white workers changing and taking up the struggle for equality.

For instance, they had a struggle in a union meeting about whether Blacks should get equal strike benefits and have an equal voice in running the union, even though they hadn’t been in the mill as long as the whites. I saw the wife of a Klan member, who was one of the strikers, take a stand that Blacks should have an equal say, an equal voice, and benefit equally from the strike. She also became real close with a militant Black woman.

That really changed my view, because what I had seen before was whites behind shotguns, burning crosses, wearing sheets. I realized I had been isolated from whites and the white community.

How would you sum up these lessons?

I think there’s a struggle that’s got to be waged among revolutionaries in this country against a subjective understanding of the white workers, against viewing them narrowly and empirically and drawing the wrong conclusions.

I think this is where we made some real gains in the McQurter case. It was a real blow against subjectivism, seeing that good ideas and bad ideas exist side by side among the white workers, just as among Blacks or any other nationality workers. The struggle has to be waged to win people over on the basis of their own experience. In one community, for instance, we would find both very progressive and very backward ideas in the same family, or even in the same individual. It’s going to be a protracted struggle and it can be done. But it won’t be done unless we defeat a subjective view towards white workers.

I’ve made some mistakes. I’ve worked in the same plant for many years, but initially in the plant I didn’t want to go along with the racist seating patterns in the cafeteria and with other attitudes among whites towards Blacks. So I took a stand of associating with Blacks and espousing my ideas to them about what I thought about the Black struggle.

But I was making the same mistake of letting my old view of white workers guide my practice. I was cutting myself off and isolating myself from the white workers. I wasn’t applying tactics to win people over. This played right into the hands of the bureaucrats. That’s just what they wanted to do–isolate me.

Something else I learned is that you have to defeat a dogmatic view that when working among whites, you must lay out a whole view of self-determination and a full revolutionary program all at once, and if they can’t accept that right away, then you can’t work with them. In the white working class communities, you have to take up the struggles that are on the minds of the people. We used to think that you take the Gary Tyler case to white workers and if they can’t unite, then they’re not ready for any kind of struggle. Now in the McQurter case, we did take the Gary Tyler case into the white community. After we had had a rally the day after McQurter’s murder, then one of the first things we did was to show the Gary Tyler film in the streets. Because of the work we had already done, we got an excellent response. In fact, white workers who are now members and leaders of SCEF were reached by that movie. They said right after the showing, “We want to work with you, we want to sign up, and we want to go out and get other people to fight against Bennie McQurter’s death.” So taking up the national question in this way didn’t isolate us at all. But if we had just gone in and shown the film, divorced from any other struggle, we would have gotten an entirely different response.

Can you tell us some more about how you organized in the community? What methods did you use?

The method we used was the work team, relying mainly on people from the community. We took the view from the start that we weren’t going to take a whole bunch of people from the outside and go in there and overwhelm everyone. We didn’t want to pull people out of work they were doing in other places, send them in for a quick flash of activity, and then they would have to leave.

Instead we went in with a small group of people who were committed to stay awhile and to rely mainly on organizing people from the community. That is who mainly made up the work teams. The teams would go around, house to house, telling people what had happened and what was going on, in order to get them involved. Then the work teams would get back together to sum up the ideas of the people. For instance, their views of the police. Some would say it was just one or two rotten apples, others would say the police were enemies who kept the people down. Then we could see what we could unite with, and how we could take our ideas out to the people and show them how we had to organize. Then we were able to set up small house meetings, larger mass meetings and some demonstrations.

What struggles came up when you took up the national question? How did you handle it?

It would have been easy to neglect the national question entirely, but we had a struggle over how to take it up. We had a very big mass meeting, over 100 people, in a Black church in the community. The neighborhood has many poor whites, but there are some Blacks, too. At the meeting a CPML representative spoke, and members of the family and friends from the community spoke. There was a lot of singing, too.

Then David Simpson from SCEF spoke. He talked in a very popular way, giving examples from that community’s own experience. He showed how the ruling class tried to suppress the Black movement and how it was not in the interests of whites in that community. He told how the city filled the local swimming pool up with cement rather than integrate it. They closed the pool so neither whites nor Blacks could go there. He used other examples like that from the cotton mill in the neighborhood. He had worked there and he explained how it was that it was still unorganized after 80years. He said he was given a little better job because he was white and that racism of that sort was used to keep the union out.

Some people said his speech wasn’t “revolutionary enough,” that he should have put out a full revolutionary position right away. But we thought his speech was good and built a lot of unity between Blacks and whites in the neighborhood. It’s not that you don’t bring the full position up. We have and we have won people to it. But you can’t do it dogmatically.

I think the fight against subjectivism and the struggle to use science and dialectics is very key to the work. The fact is that the ruling class has ripped off the white workers, not just the oppressed nationalities. That’s what I mean by being objective. I saw a videotape of Odis Hyde, agitating to take up work with whites. He said not to forget who was out there shedding blood in this country when they were building the unions, and who was in the Communist Party. It wasn’t just minority workers, but white workers, too.

The following interview is with Mr. Wright, a middle-aged white worker who became active in a tenants’ struggle in an Atlanta housing project. He describes how his own views coincided with groups like SCEF and what arguments he use s in talking with other white workers.

How did you first get involved in the movement here?

Mr. Wright: When we first moved to this housing project in 1976, we could see what was going on–the mistreatment of the people and how the manager was acting like a dictator over the people. So we started going to the tenant association meetings. We began to bring up issues to the manager. People started calling me “big mouth” around here, so they came to me to go to the manager with them. When we had our sit-in struggle, I started meeting people from SCEF and the CPML. They started giving me brochures and having talks with me about what the views of the communists are. It broadened my views, and after the struggle was over, I became a member of SCEF and the National Fight Back Organization. Then someone showed me some of the writings of Mao Tsetung and I went on the Fight Back trip to China.

What are some of the main things you learned from your trip to China?

I basically learned that there is something better than this so-called “democracy” system that we have here. It’s like what I told this one politician who came down here two months ago. I told him they needn’t come down here to solicit votes anymore because this system hasn’t worked for 200 years, so don’t tell me you’re going to get it to work in the next two years.

So that’s how I got involved in politics. But I don’t call it politics, I just call it fighting for the basic rights of the people. The only thing I know about politicians is that I can’t stand them. If it wasn’t for the poor people, these rich people wouldn’t be rich because we make all the money for them. But they act like when we get welfare or food stamps or look for a job, that they’re doing us a favor, that we’re looking for handouts. It makes me mad just to think about it. They give us rats and roaches because it’s bad for us. Well, this may sound like a j oke, but if communism was really bad for us, then they would have given that to us, too. Socialism is the best system I’ve seen so far, because it’s the people looking out for each other, instead of the wealth going into a few hands.

What problems do you see in getting white workers involved in the struggle?

The politicians are trying to divide us. Living here in the Black community now for about two years, I can see it clearly. The politicians come into the white neighborhoods and say, “Look, we have to do something about these Black people, because they’re taking all your jobs away. They keep crying to the courts for more jobs, but they don’t want to work. They just want food stamps and welfare and you have to pay for it.”

Then they come to the Black community and say, “The white people are keeping you down. We’re trying to get you jobs and more food stamps and welfare, but the white working class doesn’t want you to get it.” So they keep us fighting with each other and they don’t want us to unite.

I have to get more white people involved. Blacks have been oppressed since they were brought as slaves to this country. But so have white workers. In the South, there are hardly any unions and the ones that are here, they are trying to break up. They don’t want the people to have benefits. They work the people over 12 hours a day, sometimes 7 days a week. So we got to get out and organize.

But what are some of the specific problems you run into with the white workers? How do you deal with them?

Well, a lot of white workers say, “I don’t need to fight. I have a job and a car.” Here’s what I say: “You might have a job, but you could lose it tomorrow. Maybe, .if you’re young, in your twenties, you can get another one, but when you get older, you won’t be able to. They don’t hire you when you’re forty or fifty.”

If you don’t have any money, this government isn’t going to help you. On welfare and social security, you can hardly pay your rent. You say you own a house, but if you get sick and can’t pay your taxes next year, it won’t be your house anymore. If the city decides to run a highway through your neighborhood, they’ll just take your house. It’s not yours, really. So what, kind of freedom do we have?

You say you shouldn’t get involved in the struggle, but then these politicians start a war, and there you are, across the ocean fighting somewhere, giving your life for them to make money. It isn’t your battle, but you’re going to have to fight against people who never did anything against you. Your struggle is my struggle and everyone’s struggle.

So the people tell me, “Well, I’ll think about it.” So then I show them papers that speak the truth, like Fight Back leaflets and SCEF leaflets and The Call. When people read the Atlanta newspapers, they see that they distort what happened. Then they read about the same thing in The Call and The Call has the true story. Those are some of the things that I do.

This interview is with Ronnie and Steve, two white workers at the Atlantic Steel Company in Atlanta. Recently the company started a racist campaign to downgrade Black workers. Both Black and white workers demanded a special union meeting to air their grievances on the attacks and plan a way to fight back. Many workers, white and Black, attended the meeting and spoke out against discrimination.

Why did you participate in the special union meeting held to discuss discrimination in the plant?

Ronnie: I believe that the company is out to destroy the seniority system as a whole, weaken the union and segregate the plant. This affects me as a white worker. I know the company isn’t attacking the Black workers because they like us. They sure don’t like me or any of the other white workers. They like cheap labor and if they don’t have to pay Blacks anything, they’re not going to pay whites much either.

A number of white workers came to the meeting because they saw what was happening. In order to drive the Black workers out, they had to make conditions intolerable. To set up the Black guys, they have to set production standards too high and there’s incredible harassment on the job. One white guy testified that he was threatened in so many words by his foreman into taking a job that they were disqualifying a Black worker from. The production standards were so high, he said, that it would be bad for his health. The Black guy was getting disqualified after many years on the job, and suddenly his work wasn’t any good. If they can’t get white workers to take the jobs after they disqualify the Black workers, then they hire new white guys right off the street into these high-paying jobs. That means that the seniority system is going down the drain. That endangers everyone’s job.

Steve: It’s true we have to relate to people where they are at. But we also have to raise their level. We have to overthrow the system. There’s no question about it. There’s no easy way out for the working class. And if we don’t organize the white workers, who will? The Klan or the capitalists’ bureaucrats! We whites have to do our main organizing among the white workers. Also, you can’t really organize the Black workers unless you organize white workers too. To make revolution, you have to talk to all the workers, there just isn’t any other way.

What relationship do these attacks have to the Weber decision in steel and the Bakke decision, both of which claim that there is “reverse discrimination”?

Ronnie: They have everything to do with what’s going on. The company has unleashed these attacks precisely because they are now “protected” by the Bakke-Weber cases. And why are they doing it? To drive all of our wages down and to divide us and weaken our ability to wage a strong fight in the next contract struggle, as well as our daily struggle against the rotten conditions we face.

At the meeting, I pointed out that we have to unite and rely on ourselves to fight. The federal government won’t help us–they’re behind these racist decisions. They’re promoting this myth that white workers are unemployed because Black workers are stealing their jobs. They’re trying to blame the huge percentage of unemployment on the handful of Black workers that have been hired on affirmative action programs into jobs that they have been excluded from for years.

How have you organized white workers in the plant?

Steve: The main demands of the white workers in the plant are the same ones that the Black workers have–they want a good wage, they want an end to the harassment, they want a union that they feel is going to fight for them, not just take their dues and drop their grievances.

Do you think the problem can be solved with some reforms?

This interview is with David Simpson, the Organizational Secretary of SCEF. Simpson is a well-known revolutionary activist throughout the South and has taken part in many struggles, from the miners’ fight in Kentucky to the struggle to free Gary Tyler in the Black Belt. He describes changes in his own thinking as well as summing up a number of important lessons SCEF has learned.

Tell us a little about your background and the experiences that got you involved in the struggle.

David: Well, when I was a teenager during the early stages of the civil rights movement, I actually went out and demonstrated, on my own initiative, against the civil rights workers who were sitting in against segregation. My father, although he was progressive in his thinking on some things, had the ideology of white supremacy. In fact, at one time he was a member of both the Klan and the White Citizen’s Council.

I grew up in a totally segregated situation and this was what I was taught to think. The schools I went to were totally segregated from grade one through high school. In those days the TV shows were all white, except for Amos and Andy. I never had any social contact with minority people until I went into the Navy. In the service, I learned something about the culture, the thinking and the struggle of Black people from the Black sailors. At least on an individual level, I began to look at Black people as equals.

When I got out of the Navy and went to school on the GI Bill, I got involved with SDS [Students for a Democratic Society–ed.]. One night we went to a bar with a Black member of SDS. We were served in mugs, but he was given his beer in a can and a paper sack. The bar was segregated. So the next day we had a sit-in at that bar.

So that’s how I learned, step-by-step, as well as by doing some reading, trying to educate myself about Black history. I began to understand how discrimination was connected to the capitalist system and that the only way white working people could be free was to stand up and build unity with Black people, by fighting against racism.

I just give these examples to show that sometimes people whose thinking is extremely backward can be changed through their own experience, and through the developments and movements in society. When someone has a racist or chauvinist idea, you can’t simply blame the individual person, because many people went through the same sort of situations and experiences as I did.

SCEF has had many campaigns involving white workers. What lessons have you learned?

We’ve learned that the most effective work in building unity with the Black and white workers and in drawing workers into the general class struggle can be done when an organization actively takes up the issues and concerns that the white workers have. Now in my opinion, there is no such thing as a “white concern.” What I mean are the general class demands and class concerns that the white workers have–food, housing, education, wages, demands against police brutality. Where this work is done consistently, there is the most opportunity to talk to white workers about their common interests with minority workers. It’s the best opportunity to expose the chauvinist propaganda the bourgeoisie puts out.

We must take an all-round viewpoint toward poor and working class whites. Most have a greater or lesser degree of class consciousness. But no matter how backward they may be at a given time, their situation and their own experience in this country can change things around very quickly. For example, some of the people who are in the woodcutters’ organization in Mississippi used to be in the Klan. But today these same people are very strongly against the Klan and are very sensitive to the cases where Blacks are discriminated against. They respond very quickly against it. We had a fightback conference in rural Mississippi in an area where the Klan is pretty strong. But we held our meeting at the headquarters of the woodcutters and there was little danger, since we were under their protection.

How does SCEF fight the Klan? What methods do you use?

There are two aspects to fighting the Klan, direct confrontation and education. We try to confront the Klan face-to-face when they organize. We participated in a broad demonstration of 2,000 people in Tallahassee where we physically stopped the Klan from marching.

But the other aspect, education, is essential, too. We expose the Klan’s activities in our newspaper, Southern Struggle. We show how the Klan not only attacks Blacks, but attacks and intimidates whites, too. The Klan presents itself as “fighters for the rights of whites.” Our organization tries to be out among the masses to show that it is really fighting in the interests of all exploited and oppressed people. We try to show that anyone who says they are fighting for the “rights of whites” are really not for the rights of anybody but the rich.

But the Klan doesn’t simply base its appeal solely on the question of white supremacy. It uses a lot of demagogy and tries to speak to the issues on the minds of white workers–taxes, unemployment, inflation and so forth. For example, when we first got involved in the Bennie McQurter case, several people from the community suggested that we contact the Klan for help. Their impression of the Klan was that it was a militant fighter, and the fact that is was for white supremacy was secondary. So we have to speak to these things in showing that SCEF is a real fighter for the people, while the Klan is not.

How many white workers do you think are Klan members?

The white workers who are actually in the Klan and other fascist groups make up less than 1% of the white workers in the South. Their membership is mainly based upon the small business owners, skilled tradesmen and policemen. Historically they have been run by the capitalists and the politicians. It is somewhat unusual for a white worker, even in the South, to take the step to join the Klan and become a lyncher.

I think it’s very important to make a distinction between the active Klan types and the people who just have backward ideas on race. SCEF’s stand is that we will jump at the throats of the lynchers of Black people, we will fight like hell by whatever means necessary to put a stop to physical attacks on minority people. But with other workers who have backward ideas, who, for instance, think that Blacks used to be discriminated against, but now Blacks have a better chance to get ahead than whites–well, they’re in a whole different category. That’s a contradiction among the people and we try to use education in the course of class struggle to resolve it. But as for the lynchers, that is a contradiction between the people and the enemy, and it’s handled differently.

SCEF has taken a stand in support of the right of self-determination for Afro-American people. Could you explain this position and how it relates to white workers?

Yes, SCEF took this position about a year ago. We had an extensive discussion in the organization beforehand, we printed articles and letters in our paper. The general feeling about the demand for self-determination is this: when we say that we are for the right of self-determination for the Afro-American people, it means in one sense that all the obstacles that the capitalists and big landowners–the ruling class–put in the way of the development of the Afro-American people should be fought against and done away with, and they should be free to determine their own destiny as a people.

The obstacles I mean are such things as inequalities in education, unequal opportunities for jobs, the situation where Black ownership of the land has dropped drastically in the last 50 years. I mean such things like the fact that particular cultural contributions of the Afro-American people have been suppressed and not given the opportunity to develop fully as a culture. And I mean racist terror on the streets from fascist gangs, from the police, and frame-ups from the racist court system, as well as heavy sentences and cruel treatment in the prisons. Even small Black businessmen have it harder than small white businessmen–although all small businesses are having it rough these days.

But all the classes of Black people have been affected by the national oppression of the capitalists. They are oppressed as a people. SCEF’s stand on this indicates our recognition that the problems that Black people face are more than individual problems, but problems of a whole people. It’s a demand that says that all obstacles to their development as a people should be removed.

It especially means to us that the Afro-American people have been denied political power in this area of the country, the South, where they have the majority in many areas, where their labor laid the basis of the development of the economy of the region. The Afro-American people have been denied political power since they came here in chains and they have the right to exercise political power, to determine their own destiny.

SCEF also believes that even though there has been an increase of Black elected officials in the last 15 years, this does not represent political power for the masses of Black people. We support the right of Black people to run for office and vote free from violence and intimidation. But, for instance, Maynard Jackson being mayor of Atlanta didn’t help the Black sanitation workers when they went on strike.

These are some of the things that the slogan “Self-determination for the Afro-American people” means to us and we raise it in many of our campaigns. It’s a slogan that is very important for white workers to understand. Because of the legacy of 400 years of white slave-masters and white corporation owners and the big amount of bourgeois propaganda by the capitalists in this country, there is an understandable lack of trust and skepticism on the part of the Afro-American people towards the white workers. There is an understandable skepticism about the possibility of unity. This stand of self-determination is the basis for building unity. We think the white workers have to stand up not only against individual cases of injustice against Black people, but they also have to study the legacy of oppression of the Afro-American people and they have to stand up for the rights of that nation and have to recognize in deeds the right of Black people to determine their own destiny. This is the basis on which lasting unity can be built that will lead to the transformation of the system that oppresses all the people, Black and white.

The following interview from Boston is with two white women workers, Susan and Mary. They come from a large, poor family and have worked in many factories and been on welfare. They have been militant fighters against the segregationist anti-busing movement and many other struggles.

How did you get involved in the struggle?

Mary: I got involved in a local tenants organization which was fighting against a big landlord in my neighborhood. But I realized after a period of time that they weren’t giving us the answers that we were looking for. I understood that the slum lords and all the corruption here wasn’t caused by the one landlord we were going after.

Susan: I met a woman from the Fight Back at work and 1 was talking shit about the boss, as usual. So she told me about the Fight Back and asked me to go to a demonstration for jobs. The night before we went, she and I went over to talk to Mary.

Mary: Before you knew it, I was going to a Fight Back meeting. It took about three weeks to convince me that there were no saviors among the rich politicians who were going to change our conditions. I learned that people from different classes work in the interest of their class–so the rich were not going to help us, no matter how liberal they came off.

Susan: The Fight Back was already a multinational organization when we joined, which really impressed us. They talked about the national question, which we had never heard from any of the tenants’ groups. They weren’t moralistic either.

Mary: A few months later I gave a speech at a demonstration in support of busing and against the attacks on the Black school children. I talked about Louise Day Hicks, a racist politician, who kept saying to the white people of South Boston that they shouldn’t complain about the poor school in Southie, because at least they didn’t have Blacks there. She used the racist term, of course. The ruling class doesn’t want the workers to unite. They’re afraid of our power.

Susan: I feel that if integration happened, then Blacks, whites, Latinos, Chinese, etc., could get together to fight for better schools. The schools in Boston are terrible.

Why else did you join the Fight Back?

Mary: Well, they didn’t sit on their ass. I was out there, leafletting, demonstrating and fighting against the system. After about three weeks I knew we needed a revolution, and I wanted to learn about communism. But there was a long history that, made me see it so quickly. I was brought up to think that there was something wrong with me and that’s why I was so poor. I remember cousins of mine who were married would come over all bruised and beaten. It took me a while to understand, but I realized it wasn’t that we were doing something wrong or that our husbands really hated us, it was the society that we live in. My husband busted ass working two jobs for a long time and even then we just barely stayed above water. The lack of money tore the family apart. That’s why when people told me that the working class should control the government and the economy, I really understood.

Susan: We come from a family of nine kids, with both parents. We lived in a housing project because where else can a poor family with nine kids live? My father was a factory worker all his life and my mother worked when she could–and took care of the kids. By the time I was fifteen I was going to get thrown out of school, so I walked out and got a job at an electronics factory and I’ve been working in factories ever since, on and off, of course, because of layoffs and getting fired.

After the civil rights movement and Martin Luther King being killed, they started a liberal program supposedly to train poor whites and minorities. In the course of the program, we went on strike because we wanted them to teach us Black history. Otherwise all we learned was how to run a mimeo machine and make coffee. So after six months I went back into a factory.

On my next job I only got half as much pay as the men doing the exact same job. We fought and the men supported us, but we never did win. The company moved to the suburbs. In each place I worked I ended up involved in struggles. I didn’t understand the war. I was looking for something, but I didn’t understand what. I knew the rich got richer and I was getting poorer, but I didn’t hear anyone speaking to my needs. I had seen politician after politician selling out the people. I knew it was a corrupt society. So when I met people from the CPML–it was the October League then–they talked to me about revolution and socialism. I was very open-minded and wanted to study and get involved.

Mary: When I got involved in political struggle through the Fight Back I learned that when people were united, they can win. All my life I was taught that people were basically bad, that you couldn’t trust anyone, that even your best friends are out to get you. I began to see that people are OK, it’s the fact that they’re so ground down by the system, they do what they have to do to survive.

How do you see going out to other white workers and winning them over?

Mary: I think it’s very important not to go out like a moralist or missionary. We’re not going out to tell people to love each other. You have to understand why it’s in your interest. You don’t go out and fight a revolution because just Black people are kept down. You go out because the whole class is kept down.

It’s easy to fall into moralism. I got involved to help myself and my whole class, so I have to understand who I can win over to struggle with me in their own interests. White people don’t benefit from imperialism. It’s not in our interest to think we’re better than Blacks.

Susan: I used to be ashamed to say I was from the working class. You’re made to feel ashamed of your class. But when I got involved, I became proud of my class.

Some of my relatives can’t understand why they’re in such bad shape. Because no one has explained to them about the system, they are open to politicians who blame Blacks for their problems. They don’t know who else to blame. But if you sit down and explain to them what it means to come from the working class, I think you can win them over.

Mary: You’re raised to believe that you have to get out of the working class and when they can’t get out, they don’t know what to do–they feel like failures.

Susan: You can’t go to a white worker and tell them to get involved because Black people are oppressed. You have to talk about their own oppression, and then they’ll tell you about how Black people are oppressed, how they can see it.

Mary: If the national question isn’t taken up, I don’t see how we can have a working class revolution and win over our allies.

This interview is with Rick, a white hospital worker. He focuses mainly on how the national question is taken up in trade union work and provides some excellent examples on how to broaden the fight in the unions to an all-round political struggle against the bourgeoisie.

You work at a big hospital in Boston. Can you explain what some of the conditions are there and what struggles have taken place, especially where the national question has been involved?

Rick: First of all, there have been massive layoffs and cutbacks in health services, especially hurting the masses of poor white and minority workers. The capitalist class is attempting to divide us along the lines of color and nationality, pitting white workers against Black and Spanish-speaking workers. They also use the bought-off union officials to keep us unorganized.

In 1974 the segregationist movement grew up hand-in-hand with the first widescale cutbacks. Its leaders were well-known city politicians and their meetings were held weekly right inside City Hall. The KKK, White Citizens Councils, the John Birch Society–they were all pushing segregation in housing, beaches, jobs and attacks on affirmative action and women’s equality.

Clearly, these people today are part of what they are calling the “new right offensive” against organized labor. My union, AFSCME, rhetorically “condemns” this “new right” in its newspaper and says it is controlled by big business.

But we have been outraged for many years by these so-called “friends of white people” politicians. We have witnessed our numbers diminished and our job security threatened. But we have been even more outraged by AFSCME union officials not lifting a finger to stop these attacks.

Was there any struggle inside the union against these policies? What kind of action did you take?

Being a delegate to the “closed door” AFSCME Council, I learned some things about its giving financial support and other kinds of support to Louise Day Hicks, the leader of ROAR. I saw a chance to expose the bureaucrats. First I tried to make a motion at the council meeting against the union’s giving support to racist politicians. But a hospital administrator sitting on the union executive board started this hysteria, and I barely escaped the meeting with all my limbs intact!

But then the real work began. Starting with some other workers at the hospital and the October League, we circulated a petition through the hospital and some other city departments. The petition condemned the AFSCME bureaucrats’ support for Hicks and racist politicians as degrading and oppressive to minorities and detrimental to a solid front of labor in the upcoming contract struggle with the city.

The petition unleashed a lot of workers’ anger against the union leadership and really shook up the hierarchy. Department by department, workers took the petition and used it as a tool to build the union and fight for democracy, to strengthen our ability to take on day-to-day problems.

What about the white workers? Did they play much of a role at this point in the struggle?

Actually, I was surprised by the large numbers of white shop stewards who boldly used the petition. One white steward was nearly fired because of her organizing. In one city department, a white woman was elected president of her local because of her stand on this issue. Such strong stands taken at a time when the segregationist movement was at its height proved to me that white workers do not have a “blind spot” in regard to minorities.

What organizational gains came out of the struggle?

Unfortunately, our aim of consolidating a number of city workers in a fighting organization was temporarily set back. Just following the petition campaign, I was fired on the day after a strike in my department. Two years later, though, I won my job back.

But the Fight Back in this city was really born out of this campaign against the segregationists. In fact, when we first set up Fight Back meetings, the CPUSA and some top liberal labor leaders came to check us out. It was highly educational to watch these opportunists try to sidetrack us with abstract moralism and praise for the electoral system. But you should have seen how fast they ran when they learned that we were building for a militant picket line at AFSCME headquarters to present our demands!

How is the struggle continuing today, now that you have got your job back?

I have been involved in many battles where the national question has been crucial, especially to building a class struggle union. Take the shop steward election in my department. People wanted me as steward largely because of the stand I have taken on the national question, as well as the day-to-day struggles. The former president of my local, who is also an executive board member of the AFSCME council, cancelled the steward elections three times to, as he put it, “keep that communist from running.”

One interesting point about this campaign was that a white worker campaigning against me on a “white vs. Black” platform was supported by our Black narrow nationalist local president and by our Black foreman. But the workers were not fooled. A majority of white workers joined the Black and Puerto Rican workers, forced an election, and I won most of the votes cast.

As a low-level union leader, I have been able to use my position to expose the role of the segregationist politicians by linking their attacks with the hospital cutbacks. For instance, I got together with other white, Black and Puerto Rican workers from my department and we wrote a speech for me to give at a city council meeting. I attacked a so-called “populist” city counciler, who is a leader of ROAR, at a hearing around budget cuts. The chairman tried to gavel me out of order, but I had support from many of the people present and I continued my speech. As he pounded the gavel, I yelled: “It is no wonder this ’populist’ has done nothing about the cutbacks at the hospital over the years, considering his direct ties to the segregationist White Citizens Councils and his leadership of ROAR!” When I finished, he had no verbal supporters and could only look down at his feet in silence.

The next day at work a spokesman from an organization with ties to the KICK called me over the phone and expressed his organization’s displeasure with my speech. Actually, his real displeasure was with the support it had amongst many white workers which the Klan had been trying to organize.

I think these experiences of ours refute the view that white workers are “too backward” to unite with minorities. But I should also add that there is more to winning white support for the democratic rights of minorities than one-sidedly taking up only these kinds of campaigns, although they must be taken up. In organizing a class struggle union, all the issues affecting all the workers must be organized around in order to win people’s trust.

The following interview is with Jim, a young white worker. He describes some of the particular problems and strengths of taking up the national question among white youth, especially the poor and unemployed. While initially attracted by the “militancy” of the Klan and the Nazis, he was won over to the revolutionary line of the Communist Youth Organization.

How did you get involved in the struggle?

Jim: I got involved through my sisters. I was a heavy drinker and I had a lot of racist ideas. My sisters got involved in a tenants’ group, then the Fight Back and the October League. They would come over and talk to me about politics, about China and about national oppression in the U.S.

At first me and my friends would drink and laugh and call my sisters “nigger lovers.” But after a while, I began to go over to my sisters’ house to hear the politics, although they thought I just came over to argue. Finally, they convinced me to go to the National Fight Back Conference in Chicago. After that I met people in the CYO and they recruited me.

Could you explain how your views changed towards Black people?

Well, growing up I wasn’t completely racist, but I was close to it. I never beat up a Black. A counsellor of mine in a halfway house I was hooked up with taught us about Hitler and tried to get us to be Nazis. But after I got out, I ran into people from the Black Panther Party. I liked them because of their militancy and because they were against the system.

Why did that attract you? Why were you against the system?

Well, I was poor and always getting into trouble. A lot of people thought I was an idiot because I couldn’t read. A few years ago, a young white kid was killed by the cops in a housing project here. The cops had said they were going to get this kid. So one night he was gone on downers and he broke a window. The cops busted him and cuffed him, then beat him to death.

Hundreds of people demonstrated, demanding that they throw the cops off the force and charge them with murder. A mass meeting was called and people stood up, crying and testifying about the long history of police brutality in the neighborhood.

But the cops got off. Four kids jumped one of the murderers and beat him up. Then they got busted. At the time, I didn’t understand imperialism, but I saw it. The U.S. is supposed to be the land of freedom and democracy, but the people couldn’t get those cops off the force even though they were murderers.

Why did you join the CYO?

I saw that the CYO was out to support the people. They were all right. I liked to go to demonstrations. It was exciting, a lot of fun. They showed me the Red Book and I read the section on “Serve the People.” I got turned on, even though the last thing I had wanted to be was a communist. I wanted a Cadillac and it took me a while to give those ideas up.

I didn’t get won over on the national question very easily. At first I thought these political people raised Black issues in order to be against the white workers. But then I began to understand it wasn’t that way. It was important for me to build unity, so I began to take up the Gary Tyler case. I even tried to win some of my friends away from the KICK, which was trying to influence them. And eventually, one of these guys even helped to do security for a Gary Tyler march and was willing to take on ROAR and the Klan.

This last interview is with Cole Younger, a white Southerner with a number of years of experience in basic industry. He is a leading member of the CPML and active in its trade union work. In addition to discussing the national question, he stresses the significance of the Party for the working class.

Could you tell us something about your experience growing up in the South?

Cole: Well, I was born in Savannah and for most of my youth raised in West Georgia. Southern regionalism was very strong among us, particularly in my early teens. “Dixie” was about the first song you learned the words to and confederate flags were as common as grits.

For most of us, this didn’t reflect a conscious support for 400 years of slavery. I believe it was more related to the backwardness and poverty of the South that was evident everywhere. As youth, we thought the South had been messed over bad. We believed what we had been taught–that the Civil War was a rebellion against injustice towards the South. We identified with this rebellion.

If we’re to expand work among white workers and particularly white youth in the South today, it’s important that we understand the two aspects of these rebellious sentiments. Especially today when regionalism is having a big revival among Southern white youth.

As communists, we unite with the just hatred Southern white workers have for their present situation–lower wage scales, backward housing and education, lack of unions and so forth. We unite with the discontent and organize the fight against these conditions. But in the course of organizing this fight, we must educate and win white workers to recognize the true source of their situation– capitalist exploitation and the historic national oppression of the Afro-American people.

At the same time, we have to combat Southern regionalism. Southern regionalism denies classes and class struggle in the South and inevitably promotes white supremacy as the solution to the exploitative conditions white workers live under. My identification with the confederate flag as a youth is an example of this misdirected rebelliousness. The confederate flag was the flag of the plantation owners and Southern artistocracy. It represents slavery and lynchings for Blacks and never had anything in common with the poor white farmer and workers in the South. Under the confederate flag the plantation owners drove thousands of poor whites off the land and into destitution and poverty.

I tell you, it wasn’t until I started seeing Black students boycotting sporting events where “Dixie” was being played and hundreds of confederate flags would be waving that I started to question some of the “Southern values” I’d been brought up to believe in.

And who are some of the biggest promoters of this Southern regionalism today? It’s capitalist front groups like the Ku Klux Klan who demagogically speak about the backward state of the South. They’re trying to turn the rebelliousness among white youth and the discontent among the white workers in a reactionary direction. Now you got the Klan opening up their rallies with country rock bands playing “Dixie” while you salute the confederate flag.

Of course there is a regional question in the Deep South. It’s based on hundreds of years of slavery and bondage to the land for Afro-Americans. Over this time Black people developed into a nation in the Black Belt region in the South–a nation oppressed by U.S. imperialism.

The thing is, the special oppression of the Afro-American nation hasn’t just affected Black people. It’s ensured that the whole Deep South region remains in a more backward state. Where has the Southern white worker benefitted from capitalism and the special oppression of Black people? He’s exploited by the boss–in fact his wages and overall living standard is considerably lower than that of white workers in the North. The only democracy he knows is the right to elect plantation owners and bankers into office. The Klan and police ain’t his friend, ’cause as soon as he starts to resist, unite with Black people and fight for his class interest, he’s fired, jailed or shot down.

And the bosses have used discrimination to try and trick the white worker into thinking that he’s better–that Black people and not the bosses are the cause of his problems. The divisions created between Black and white workers have meant a relatively weak labor movement throughout the country, a low percentage of workers organized into unions, especially in the South, and the few unions that do exist being run by bribed corrupt officials.

This situation will not change as long as there is capitalism. We recognize the regional situation in the South and know it can be solved under socialism. When the multi-national working class takes state power, Afro-Americans will decide the destiny of their nation. Special steps will be taken to ensure that the remnants of national oppression and backwardness of the Deep South are eradicated. And for the first time the masses of the Deep South region, Black and white, will enjoy the benefits of socialist freedom and democracy.

Did you ever oppose racism as a youth?

Sure, along with a lot of white kids I knew. We opposed specific acts of discrimination, especially when it interfered with something we were trying to get done. For example, I went to a working class high school. It was located near a Black community and a handful of Black students went to school there. Now we had a helluva football team, a real contender in the AAA division. Three of the Black students played on the team. Now these dudes weren’t no second stringers, but they had to work twice as hard to win their rightful position on the team. This was obvious to a lot of us.

Well, we used to have week-long summer training camp and the whole team would camp out on the gym floor. The three Black players would be in the corner and there wouldn’t be another sleeping bag within 20 feet of them. It wasn’t long before this small group of hard-core crackers started telling racist jokes–real loud. The tension was building, and the whole gym became stone quiet except for the loud racists. Everybody was waiting to see who was going to throw the first punch. So a group of us white players picked up our sleeping bags, walked over and layed them down in the corner where the Black players were. Then we went over to the crackers and told them real politely that if they didn’t cool it we were going to kick their ass– no more jokes. The majority of the players on the gym floor supported what we did. And I’ll tell you, after a couple of days there were white players, who had never spoken to the Black players, starting to talk to them about things other than football.

My point is this. Southern whites have seen racism all their lives. We saw it in the segregated schools and communities, the Jim Crow bathrooms and water faucets, and we were taught it everyday by our school teachers and preachers. If I was to say that I wasn’t infected by racism as a youth, I’d be lying. But I say infected, because I know that racism among white workers is an illness that you didn’t really want and you sure don’t need. White chauvinism goes against the grain and against your everyday experiences. You come to understand this over a period of time–the more you understand it, the more you fight it.

But I know from my own experience that understanding the source of national oppression, its effect on the working class movement and how to fight it doesn’t come overnight. Our organizing among white workers must combine consistency with patience.

For myself, the civil rights struggle and Black liberation movement had a pretty big impact on my way of thinking. It’s had an important influence on a lot of white workers. For one thing, racism came sharply into focus as a basic tenet of U.S. society. We saw tremendous unity in the Black liberation struggle, and the fact that with this unity you can fight. It was also significant that white students were supporting this struggle.

It was also the first time that I became really aware of the demands that Black people had in their fight against oppression, from basic democratic rights to the right to self-defense. I supported many of these demands even before I was ready to take part in the struggle.

The biggest leap for me was when the Black liberation movement started to penetrate the workers’ struggle. It was inevitable that this would happen when you consider that 90% of Afro-Americans are workers and something like 1 out of 5 workers in the U.S. are Black.

Events like Martin Luther King getting assassinated in Memphis while organizing sanitation workers, and later the League of Revolutionary Black Workers taking Marxism to auto workers in Detroit, said a lot to me about the direction the workers’ struggle had to go in.

This is important to take note of. We see two great movements growing in the U.S. The movement of the oppressed nationalities and the multinational workers’ movement. These two movements must be united if we’re to be successful in overthrowing capitalism and building socialism. At present there is a significant gap between the two movements. The national liberation struggle is a number of steps ahead of the workers’ movement. In fact the nationalities movements have played a big role in advancing the workers’ struggles and drawing them forward. The rank-and-file caucus movement, the struggle against the trade union bureaucrats, the militancy in some of the labor struggles and some of the advances in internationalism being spread among the workers–all these have been greatly influenced by the struggle of the oppressed nationalities.

We see our communist work among white workers as a key factor in both uniting the multinational working class and building the alliance and merger of the general workers’ movement and the movement of the oppressed nationalities. In this sense winning white workers to a good stand on the national question takes on the utmost importance. This includes supporting the fight for democratic rights as well as for self-determination for the Afro-American people.

Many white workers have been fooled by the bosses’ lies that they have to pay for the special demands of minority workers. This is evidenced by the support and confusion that has been whipped up by the bosses with their racist “reverse discrimination” schemes like the Bakke and Weber cases. We say the special demands of minority workers are just and we demand the bosses compensate.

There are inequalities between white and minority workers. You won’t win any white workers to revolutionary struggle if you try to slight or deny this. But these inequalities are created by capitalism and national oppression. Discrimination hasn’t benefitted the vast majority of white workers. The only white workers who have gained from national oppression are the labor aristocrats who live and think like the bosses and presently control our trade unions. As far as the masses of white workers go, national oppression has weakened their ability to fight against capitalism.

We don’t propose a “take-away” program for white workers to solve national oppression. White workers giving up the extra money they make on the job or their house in a better neighborhood is not going to end discrimination. Instead we propose unity with the oppressed nationalities in the fight for equality and socialism as the only way white workers can better their own situation and win freedom from exploitation and oppression.

After meeting communists, I came to understand what Harry Haywood says: that racism is just a smokescreen to cover up national oppression and exploitation of the entire working class.

You are a leading member of the CPML and active in the Party’s trade union work. How did you come to see the need to join a Marxist-Leninist organization?

The first time I had any real contact with organized communists was in the early 1970s. It was an Atlanta-based group known as the Georgia Communist League. They put out a monthly paper called The Red Worker. Now I had met a few of these folks about a year or so earlier when I was doing some GI organizing in my home town. I’ve got to admit that at first I didn’t accept some of the things they were talking about, there were a lot of things I just didn’t understand. Plus they weren’t engaged in much organizing back then, at least anything that was real visible.

Well, by the time I had any regular contact with the GCL, my family and I had moved to Dalton, a small mill town in north Georgia. I became active in an organizing drive in my shop and we used to put in about four hours on the road every Sunday to meet with the GCL in Atlanta and study some Marxism. At that time our main concern was organizing a union in Dalton. Dalton produces the majority of carpet for the U.S. and there’s never been one successful organizing drive there. The GCL was trying to convince us to move to Atlanta. They pointed out the futility of isolated, individual organizing and stressed the need for communists to unite into one party. They were eventually able to convince us that the mills in Dalton could be better organized with the leadership of a communist Party that had a base in industry in the major cities.

Well, we lost the organizing drive. The Teamster bureaucrats didn’t do anything but call a few meetings, give us some cards and talk about dues check-off. There were divisions between the white and Black workers that we weren’t able to deal with and the company was able to buy off a couple of key guys with truck-driving jobs. It taught us something about.fighting alone and with primitive methods of organization. Soon after, we packed up and moved to Atlanta to join the GCL.

Looking back, I believe there were several key factors which won me to joining the GCL, which was soon to merge with the OL. Most important was their seriousness and dedication to revolution. I saw this in the emphasis they put on consistent and patient theoretical training, particularly on the Afro-American question, which helped to explain many unanswered questions and experiences I had had growing up in the South. Also important was the fact that their main organizing was in the factories.

What can the CPML offer white workers that they can’t find in a mass organization, like a union or a tenants’ group?

The CPML offers white workers the theory of Marxism-Leninism. This is necessary so they can understand their own class interests and recognize their allies. The Party shows that the struggle is much broader than one factory or industry, one community or city. It’s for the workers to take political power, to rule all of society. The white workers we have recruited have been some of the best organizers in their various shops, locals and communities. Having joined the Party and become trained in the theory and practice of Marxism-Leninism-Mao Tsetung Thought, these workers become even better organizers, a different kind of organizer. They become fighters for all the people, communist fighters in the spirit of revolution.

Within the CPML, we have initiated a campaign to expand our work with white workers–in the shops, unions, white working-class communities and schools. We implement a “division of labor” in our Party to more effectively carry out this work. Our national minority comrades mainly work with workers of their own nationality. Our white comrades work mainly with white workers. Although it’s not an absolute rule in every case, this has been a good thing for our work. After all, who is better qualified to organize white workers than someone like myself who has many of the same experiences, education and cultural influences as other white workers?

The main thing is to see this “division of labor” politically, to see how it promotes unity. When you have the white comrades taking up the struggle against chauvinism among whites, it makes it all the easier for Black comrades to combat nationalist and separatist tendencies among the Black workers.

Also the party is the highest form of working-class organization. It provides the discipline and collective methods necessary to make revolution successfully. In the class struggle there are all kinds of shifts, all kinds of twists and turns. With the collective leadership of a party and its organized ways of summing up experience all over the country and the world, you can correct mistakes and build on advances. The party is the most important weapon the workers have.

This series of interviews by no means exhausts the subject of the white workers and the national question. More areas need to be covered and some need to be gone into in more depth. Nonetheless, the comments above contain a wealth of experience with many lessons. As few of the most important can be summed up as follows:

–The masses of white workers are by no means “bribed” or “bought off” by imperialism. In fact, as part of the working class, they have nothing to lose but their chains in the struggle for socialism. This was shown through the dozens of examples of exploitation, impoverishment, police terror and brutal social conditions that those interviewed have lived through. At the same time, there is a stratum within the working class which has benefitted from imperialist exploitation. This is the labor aristocracy which lives and thinks like their capitalist bosses. The labor aristocracy includes the top officials in the trade union movement and though they compose a small minority within the working class, their influence is still very broad. These traitors must be driven from the workers’ movement.

–To work among the white workers, organizers must take an all-sided, objective viewpoint. They must combat views of disdain and contempt for the working class pushed by the bourgeoisie. At the same time, we should not one-sidedly romanticize the working class but view it scientifically, as comprised of advanced, intermediate and backward elements. This means the workers as a whole are still largely influenced by bourgeois ideology.

–The fight against national oppression is in the class interests of all workers, including whites. First, this is true strategically, in that the working class needs the oppressed nationalities as a powerful ally in smashing the rule of capital. But it is also true in the immediate sense, in that workers of all nationalities must unite in order to defend their day-to-day interests.

–When organizing white workers, we should not carry out the struggle for unity in the fight against discrimination and for self-determination in an abstract or moralistic manner. Years of chauvinist education will not be overcome with one discussion. We can win white workers to the fight against national oppression through patient education carried on in the course of fighting around the class-wide issues on the workers’ minds. At the same time, winning white workers to the fight against national oppression and for self-determination is a necessity. Otherwise the unity among the people of different nationalities will be superficial and easily destroyed.

–White chauvinism is a fact of life among white workers under capitalism, but so is opposition to chauvinism. Here it is important to make a distinction between the majority of white workers who have been influenced by backward, chauvinist views and the small core of fascist elements who are actively engaged in the counter-revolutionary attacks on minorities organized by the KKK and similar groups. The first is a contradiction among the people, while the second is a contradiction between the people and the enemy.

–The national movement itself and its role in society play a progressive role in developing the class consciousness of the white workers.