Although Maoism, self-defined as an adaptation of Marxism-Leninism to the particular conditions of China, refers to the specific experience of China before and after 1949, it would also be used to designate a political tendency composed of a group of organizations that emerged throughout the world in the 1960s and 1970s. Maoism outside of China was shaped by the impact of two distinct phenomena: the Sino-Soviet conflict created the first wave, and the Cultural Revolution, and concomitantly student radicalism in West shaped the second wave in the First World. Each had their own specific characteristics. Like elsewhere in the Western world where Maoism outside of China emerged, it emerged in Portugal at two separate times. J.Perez Serrano describes the anti-revisionist Marxist-Leninists as comprising three branches: those emanating from a Party heritage, the student milieu and the third that arose outside of these.[1]

The first wave evidence of dissident voices in the clandestine Portuguese party emerged from the late 1950s with criticism of the revisionist line of the CPSU under Khrushchev. Again, as elsewhere, advocates of Stalinist orthodoxy and the heritage of the Comintern, emboldened by Chinese criticism, challenged the entrenched leadership and eventual left the organisation. In Portugal the anti-revisionist criticism from Francisco Martins Rodrigues, a militant of the PCP since 1951 and member of the group of leaders that has escaped from Peniche jail with Cunhal in January 1960, coincided with a very critical and troubled time for the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP), as Cunhal struggle against so-called “rightist deviation”. Disagreements at the August 1963 Central Committee meeting saw Rodrigues accuse the PCP of mere electoralism. Expelled in December 1963, Rodrigues, Ruy d’Espinay and John Pulido Valente, established Frente de Acção Popular, the Popular Action Front (FAP) predating the formation of the associated CM-LP, Portuguese Marxist-Leninist Committee , Comité Marxista-Leninista Português in Paris in March 1964.[2]

In the second Maoist wave the majority of its members had not passed through the ranks of the PCP and had already been influenced to a certain extent by the radical student culture, typically of the MRPP/ Movimento Reorganizativo do Partido do Proletariado. As a whole, the Maoist organizations represented essentially a young urban phenomenon – although it had some impact on intellectuals and the fringes of the working-class movement – which took the student world as its favoured arena for intervention and recruitment.

Despite the differences between the first and emerging second waves of Maoism, a theoretical bridge between these waves was the coherent theoretical corpus, produced between 1964 and 1965, influenced by texts written by Francisco Martins Rodrigues and the pages of Revolução Popular (Popular Revolution). These documents allowed for an ideological demarcation to be established in relation to the PCP and offered a perspective on revolutionary action in the country. Most of the dissident communist groups that emerged in the 1960s, although without renouncing the theory of violence, in practice developed exclusively political strategies. Many observations on the Western Maoism of the period try to characterize it in its anti-revisionist phase as the mere sectarian recycling of a Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy whilst in the second wave of radical appeal, that European based adherents essentially sought to mechanically transplant the Chinese model to other places. However, for the second wave activist, Cardinal argues that Maoism,

“offered them a new confrontational form of practice that traditional communism had not provided and an ideological grammar that combined the almost total politicization of all aspects of life with a very concrete focus on the war and ways of rejecting it.”[3]

Portugal like Greece under the Colonels, operated under a military backed state authoritarianism, associating with this was a wide-ranging conservative Catholic morality which helps explains the character of the resistance. There was the almost total lack of organized attitudes associated with social radicalism, which, for example, fuelled the European Maoism involvement with progressive social movements such as the feminist and gay movements. It was the specific factors of the Portuguese dictatorship and social culture which relegate other political and cultural forms of combat to secondary concerns. More than one commentator observes the subjective factor that state authoritarianism constrained political activity, however it also endowed it with a “romantic” dimension, in which risk and courage would emerge as the elements that shaped the experience of militancy. The expectations and effects of repression shaped the opposition organizations:

“The authoritarianism of the Estado Novo and the physical and psychological risk that the armed conflict in Africa introduced into the lives of each young person and, by extension, their circle of family and friends, significantly overdetermined the repertoire of protest.”

State censorship and repression restricted the type of protest that was possible, forcing political activities into a clandestine or semi-legal existence, making risk as a permanent feature of militant life. The complex of laws, courts, prisons, and police designed to monitor and punish dissidence constituted a “punitive violence” and confirmation on the ideological description of the state’s function that was experienced whenever compliance failed.

The overseas formations were important in the development and sustaining the Portuguese anti-revisionist Marxist-Leninists, but their complexities deserve a separate treatment and are only lightly referenced here. Nor is this the place to dissect the multitude of fractious groups and political tendencies who emerged in competition, to challenge the revisionism of the PCP alliance with MFA, to shape the outcome of the carnation revolution.

Well served by domestic sources, and studied in Brazil, the history of Portuguese anti-revisionist Marxist Leninists/Maoism is less familiar to an English language audience. This introduction to the evolution of that tendency draws upon selected primary and secondary sources to provide a flavour of what is available in Portuguese and map out the broad contours of what begun under a clandestine existence, and the transformation, after the disintegration of the Estado Novo (the Portuguese “New State” dictatorship), that saw legalization and construction of bourgeois parliamentary politics during the post-April 74 transitional years the high water moment for the ML movement, and the fading movement’s eventual political disintegration by the early 1980s.

[1] SERRANO, Julio Pérez (2018) Radical Left in Portugal and Spain (1960-2010) in Challenging Austerity : Radical Left and Social Movements in the South of Europe Edited by Beltrán Roca, Emma Martín-Díaz and Ibán Díaz-Parra. London Routledge

[2] See José Pacheco Pereira (2008) “O Um Dividiu-Se Em Dois“ Aletheia = a small portion of JPP’s doctoral thesis devoted to the history of radical far-left between 1964 and 1974.

[3] CARDINA, Miguel (2017) Territorializing Maoism: Dictatorship, War, and Anticolonialism in the Portuguese “Long Sixties“. Journal for the Study of Radicalism, 11.2, Fall 2017.

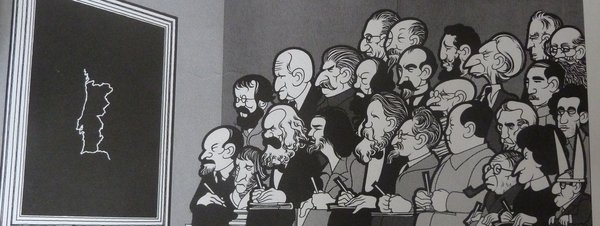

Family Tree of Portuguese Anti-Revisionism

Anti-Revisionist Posters from the Portuguese Revolution, 1974-77

Anti-Revisionism in Portugal - A Note on ... April 25, 1974

Lisbon Communists Gain Quietly [1974]

Report on Portugal [1974]

How the Left Was Trapped [1975]

Portugal... A New Dictatorship

Portugal’s last Maoist guerrilla fighter

Notes on the Comité Marxista-Leninista Português

Message to the Belgian Communist Party

Class Struggle or “Unity of All Honest Portuguese”

Notes on the history of the PCP (ML)

Portugal Maoists Fighting Voting Ban by Henry Giniger

Appeal to the European Patriots and Democrats

Lisbon Conference Against the Threat of Russian Imperialism

Should We Not Attack Social Fascism?

Denouncing Soviet Sabotage of Angolan Independence

Fifth Plenary Session of PCP (ML) Central Committee

PCP (ML) Message on the Death of Mao zedong

Chairman Hua Meets Delegation of the Central Committee of PCP (ML)

Seventh Congress of the PCP (ML)

PCP (ML) Seventh Congress [Peking Review]

Notes on the Fusion of Small Groups

The Maenist Marxist Leninist Studies Group (GEMLM) by Jose Pacheco Pereira

The Paris Commune Cell by Jose Pacheco Pereira

The "Reconstitution" of the CMLP Party by the Marxist-Leninist Committee

About the Current Situation by the CMLP

The People's Cry Newsletter #2

Second Congress of the Portuguese Communist Party (Reconstructed)

1976 newsreel coverage MRPP rally

People's War, the colonial-imperialist war

Revolution and counter-revolution in Portugal Interview with a representative of the Central Committee, November 1974

The five constituent points of the Movement for the Reorganization of the Party of the Proletariat

Program of the Movement for the Reorganization of the Party of the Proletariat

Statutes of the Movement for the Reorganization of the Party of the Proletariat

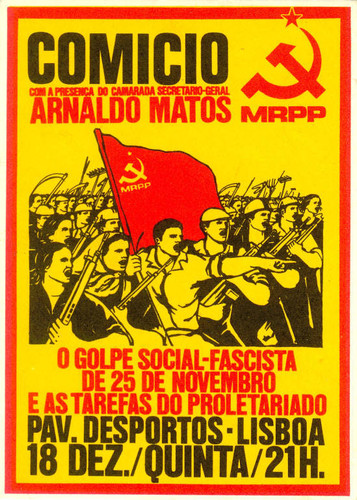

July 18, 1975 - Release of Comrade Arnaldo Matos and MRPP militants arrested by COPCON/PCP

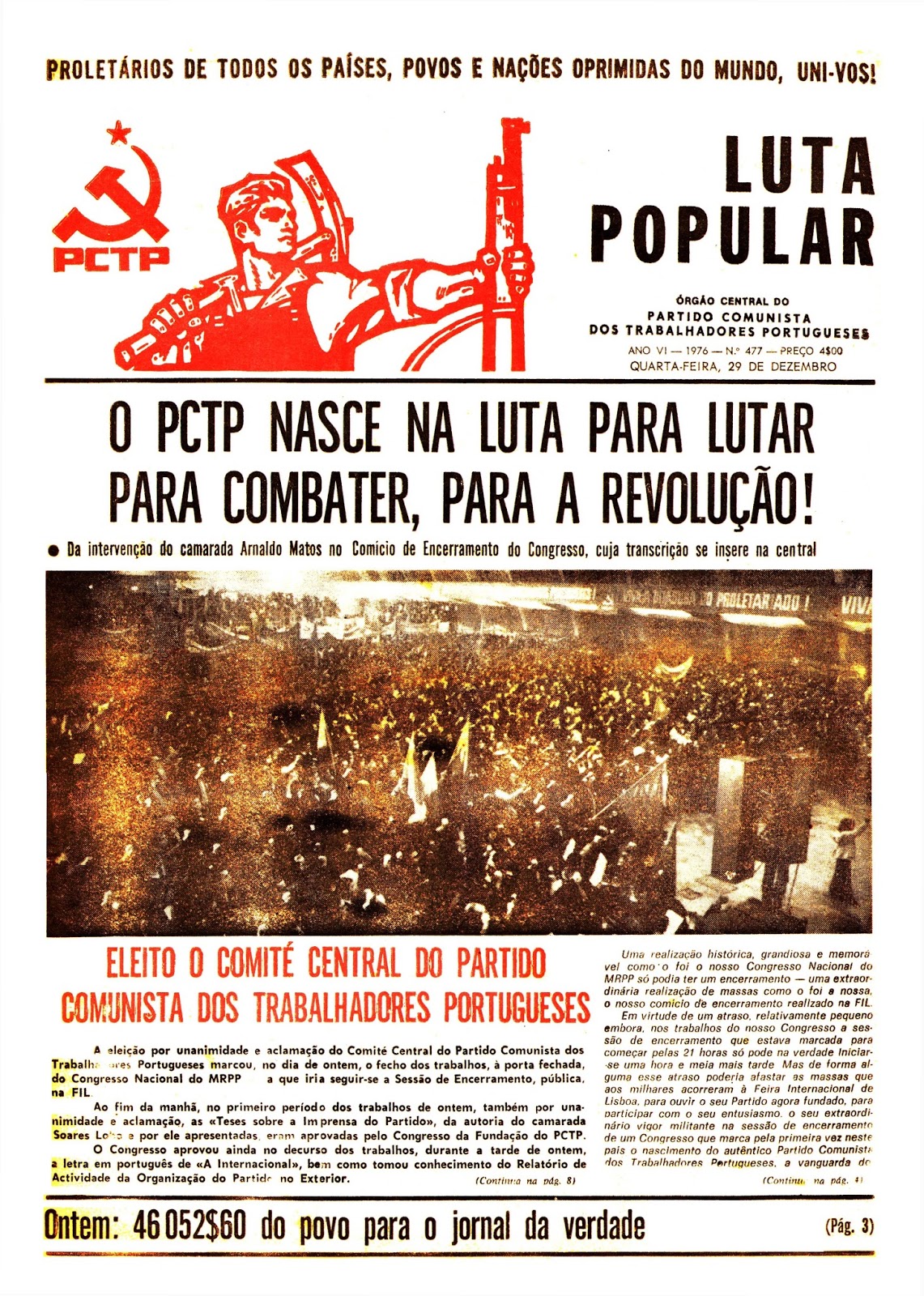

MRPP/PCPT National Congress - Central Committee Elected

First Plenum of the Central Committee

Urgeirius Theses by Arnaldo Matos

A Century Later: Where We Are and Where We Go?

Arnaldo Matos had a “moving” farewell ceremony

“The communist has to dedicate himself to the cause of communism and has no time for anything else.” [Arnaldo Matos, 1939-2019]

Between the "despair" and the charisma of Arnaldo Matos by São José Almeida and Leonete Botelho

Bourgeoisie, armed struggle and the "parasites." The phrases and targets of Arnaldo Matos by Ruben Martins

Let us reject a provocation to memory and dignity of Comrade ARNALDO MATOS! by F. Firmino