Paul D’Amato Archive | ETOL Main Page

Origins of the War

From International Socialist Review, Issue 7, Spring 1999, pp. 10–11.

Downloaded with thanks from the ISR Archive Website.

Marked up by Einde O’ Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

|

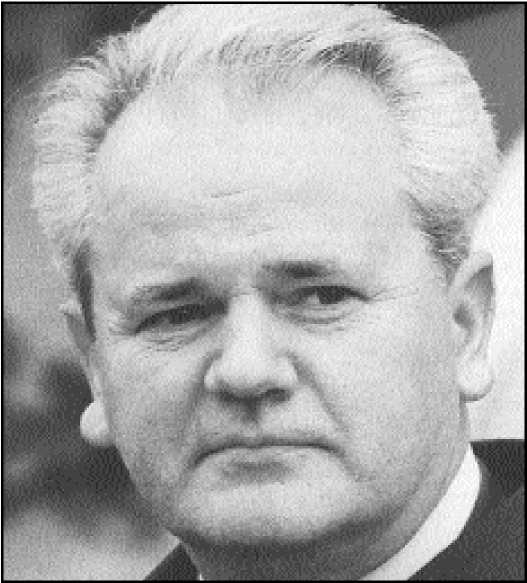

SLOBODAN MILOSEVIC, a former banker and second party leader in the Communist League of Serbia, was the first to play the nationalist card. Milosevic was not a nationalist by background. He merely saw that he could use nationalism to deflect working-class anger and secure his rise to power within the ruling Serbian party apparatus.

Beginning in 1987, he began a sustained campaign to whip up Serbian chauvinism against the Albanian-speaking majority in Kosovo. Milosevic hammered on the Serbian-nationalist myth that Kosovo is the cradle of Serbian civilization, despite the fact that Serbs make up just 10 percent of Kosovo’s population today. He organized a series of mass rallies around Serbia, including one in Kosovo itself. Unemployed young men we re paid to attend these rallies to listen to Milosevic’s Serbian-nationalist hysteria. His speeches made reference to the Battle of Kosovo Polje – a battle in 1389 in which, according to nationalist mythology, the Serbs martyred themselves in defense of Christendom against the advancing Ottoman Empire. In reality, Serbs and Albanians fought alongside each other in that battle.

“Six centuries [after the Battle of Kosovo Polje],” Milosevic proclaimed at the Kosovo rally, “we are again engaged in battles and quarrels. They are not armed battles, but this cannot be excluded yet.” [4]

Serbian nationalists had long claimed that Serbs in Kosovo were an oppressed, embattled minority. As evidence they pointed to the flight of Serbs from the area. In reality, thousands of people fled from the region on a yearly basis, because it was the poorest region in Europe. Unemployment ran more than 50 percent. In spite of efforts over the years by the Yugoslav government to force Albanian-speaking residents to leave and bring in Serbian colonists, the Serbian population has continued to decline. In any case, the nationalist message hammered over and over again by Milosevic was the idea that if the Yugoslavian state disintegrated, whole sections of the Serbian people – in Croatia, in Bosnia, and in Kosovo – would be left to suffer under the control of other nations. Milosevic based his claims for a greater Serbia on the need to unite all Serbs in Yugoslavia into a single state.

In 1987, Milosevic triumphed in a bitter contest for control of the Serbian party – and there by won control of the Serbian regime. He used his newly created mass base to take full control of Serbia’s autonomous provinces. Milosevic cracked down on the Albanian majority in Kosovo. By law, Albanians were forbidden from buying land. Serb-only factories were built, and Albanians were fired from their jobs. Serb villagers threw out Albanian inhabitants. To the north, in Vojvodina, Milosevic removed local party leaders and replaced them with his own loyal lieutenants .

In Kosovo, Milosevic’s 1988 attempt to remove local Albanian party leaders produced a mass response. A quarter of Kosovo’s population, about 500,000 people, marched on the capital, Pristina. At Kosovo’s largest mining complex, Trepca, 1,700 miners occupied a mineshaft and staged an eight-day hunger strike. In response, Milosevic imposed direct rule on Kosovo, occupying it with Serbian police and paramilitaries.

Alarmed by events in Serbia, the leaders of the other republics followed suit. In Croatia, Franjo Tudjman, a former general turned rabid nationalist, was Milosevic’s mirror image. His party, the Croatian Democratic Union, won elections in April 1990. He ran a campaign for Croatian independence, which went out of its way to antagonize the Serbian minority. He talked of a “greater Croatia,” courted the fascists of the Croatian Party of Rights (HOS) and declared his happiness that his wife was “neither a Jew or a Serb.”

In the summer of 1990, Yugoslavia came apart. Slovenia declared independence and held it after a desultory 10-day war in which the Yugoslav National Army (JNA) – soon to be transformed into an army controlled by Belgrade – mobilized a token effort to prevent secession. Croatia declared independence soon after.

The rival nationalisms in Serbia and Croatia reinforced each other. Tudjman demanded that Serbs living in Croatia declare their loyalty to the Croatian state, and began removing Serbs from jobs and replacing Serb policemen with Croatians. Milosevic, in turn, reminded Serbs in Croatia that the last independent Croatian state massacred Serbs and drove them from their homes. Tudjman reinforced Milosevic’s point by adopting the flag of the Second World War fascist Ustashe regime as a symbol of the new Croatian nation. Incited from Belgrade, Serb nationalists in Croatia formed the Serbian Democratic Party and gained control of Serb majority areas, declaring them independent from Croatia. Fighting began to break out between Croat and Serb nationalists in several towns.

Meanwhile, in Belgrade, Milosevic faced struggle from below. Beginning in early 1991, mass demonstrations of students and workers against police brutality and repression, and against censorship, were the order of the day. In April, mass strikes involving 700,000 workers broke out in Serbia. Milosevic had to bring in tanks to quell the unrest. Amid the rising struggle, Milosevic and Tudjman – the two men who were setting Croatians and Serbs against each other – met secretly in the Serbian town of Karadjorjevo and agreed to divide Bosnia-Herzegovina between Serbia and Croatia.

Milosevic was saved by the outbreak of war in Croatia, with Croatian militias battling the JNA – transformed by the breakup of Yugoslavia into a Serbian army. He held onto power by appealing to Serbian unity in defense of Serbs under attack in Croatia.

Here [in Croatia] there was no question of Serbs losing the will to fight as quickly as in Slovenia. In many cases the irregular soldiers [Serb civilians armed by Milosevic], charged with nationalism and bigotry as they were, were actually fighting for their own houses and villages. By the middle of September it was clear that, regardless of what schemes either Milosevic or Tudjman might have for dividing up the country, they were now locked into a vicious cycle from which there was no easy escape. [5]

Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic |

By January 1992, Serb nationalists had gained control of the Krajina, taking a third of Croatian territory. In six months of bloody fighting, 80,000 people – Serbs and Croats who had lived side by side for decades – were driven from their homes. Alarmed by the spread of war in the heart of Europe, the Western powers intervened. Tudjman – whose military was weaker – agreed hastily to a UN-brokered cease-fire that placed 14,000 “peacekeeping” troops on Croatian soil.

From the beginning, European and U.S. intervention in the conflict aimed at preventing the war from spiraling out of control – not out of concern for ordinary Serbian and Croatian victims of the war, but from a shared determination to demonstrate their capacity for common action and resolve. But every step they have taken has only served to encourage ethnic cleansing and to entrench the nationalist bullies in power. After first backing Milosevic and the integrity of Yugoslavia’s former borders, the U.S. then did an about-face and backed the independence of the new republics. Germany, a traditional ally and trading partner of Croatia, pushed hard and early for international recognition of Croatia, without in the least taking into consideration the concerns of the embattled Serb minority there.

Because [the EC, the UN and the U.S.] ignored the compromises that Yugoslavia represented in guaranteeing nations the right to self-determination in a nationally mixed area, ignored the security guarantee that Yugoslavia had provided for territories of mixed population, and did little to reassure those relegated to minority status that they would be protected, it could not reverse the downward spiral of suspicion and insecurity that was leading to war. It then assumed the role of mediator to obtain cease-fire agreements as rapidly as possible. But that meant talking to leaders who we re fighting because they could not agree, while insisting that no agreement achieved by the use of force would be recognized. It could negotiate cease-fires that froze the disputes over borders and national rights, but it could not persuade parties to disarm without providing a constructive alternative to those whose national rights were denied by the international insistence on the republican borders. [6]

As with all subsequent peace agreements in the Balkans imposed by the Western powers, the introduction of “peacekeepers” in Croatia merely froze the fighting temporarily. Quite logically, the opposing sides saw it as legitimating their claims to territories already seized by force. It there by legitimized and reinforced the need for a military solution to the crisis, i.e. the forced expulsion of people and the further carve up of the region. As the conflict spread to Bosnia, U.S. intervention became even more directly an aid and encouragement to ethnic cleansing. As future events would show, Tudjman was buying time – preparing militarily with help from Washington for a massive military onslaught in 1995 to drive the Serbs out of Croatia.

Given its three-way division between Serb, Croat and Muslim, the outbreak of war in Bosnia, egged on by Milosevic and Tudjman, was only months away.

4. Quoted in Misha Glenny, The Fall of Yugoslavia: The Third Balkan War (New York: Penguin, 1993), p. 35.

5. Duncan Blackie, The Road to Hell, International Socialism 53 (December 1991), p. 52.

6. Woodward, p. 220.

Paul D’Amato Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 24 August 2021