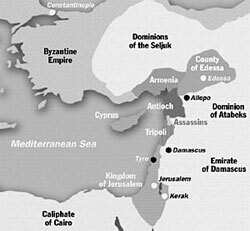

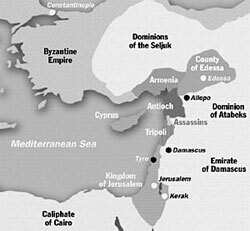

The Crusader kingdoms of Edessa, Antioch, Tripoli and Jerusalem around 1140

Neil Faulkner Archive | ETOL Main Page

From Socialist Worker, Issue 1953, 28 May 2005

Copied with thanks from the Socialist Worker Website.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

Neil Faulkner examines the medieval precursor of imperialism in the Middle East

The Crusader kingdoms of Edessa, Antioch, Tripoli and Jerusalem around 1140 |

On 15 July 1099 Jerusalem was stormed by soldiers of the First Crusade. For the attackers, who had set out from western Europe three years before, this was the culmination of their efforts – the “liberation” of the Holy City from Muslim “infidels”.

The campaign had been punctuated by massacre and mayhem. Pogroms had been launched against the Jews of Germany. The people of the Balkans had been plundered on the army’s line of march. There had been clashes with the Greeks of Constantinople (Istanbul), whom the Crusaders were supposed to be defending. Edessa had been seized not from “infidels” but from Armenian Christians. And there had been wholesale slaughter at Antioch and other captured cities.

Now it was the turn of Jerusalem. For two days after the walls were breached the Crusaders killed and pillaged. Jews and Muslims were cut down where they stood or herded into buildings and burnt alive. The few who survived were sold as slaves.

In the days following, rotting corpses having filled the city with stench, bodies were gathered up and piled in great heaps outside the walls. Meantime the Crusaders plundered the city of every scrap of wealth. Western civilisation had reached the Middle East.

The Crusade had been launched by Pope Urban II in 1095. The church, with estates spread across the whole of western Europe, was a vast feudal corporation. Now the popes aimed to turn wealth into power.

But they clashed repeatedly with the competing claims of secular rulers in the West, and their authority was challenged by a rival Christian hierarchy in the East. So Urban II’s aim in launching the Crusade was to increase the ideological, military and political power of the church.

It was also a way of diverting social discontent. Flood and plague in 1094 followed by drought and famine in 1095 had left millions destitute. Instead of anger being turned on the rich it was targeted at the Jews, while despair was transformed into the mysticism of a “people’s crusade” in which thousands set out on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

Above all, the Crusade was an outlet for the brutal imperialism inherent in the feudal order. Much of 11th century Europe was divided into landed estates (or “fiefs”) designed to support a heavy cavalryman, providing enough to pay for his armour, equipment, horses, and the luxury and trappings of a knight.

In return for their estates, knights owed allegiance to the great lords who owned the land. These lords in turn had obligations to the rulers of the feudal states. Norman feudalism was an extreme example. The Normans were descended from 10th century Viking settlers in Normandy. The native peasantry was heavily exploited to maintain a large force of heavy cavalry.

But to avoid fiefs being subdivided and becoming non-viable, the rule of primogeniture prevailed, whereby the eldest son inherited the entire estate. Younger sons therefore had to fight to keep their place in the world.

Denied an inheritance, they had to survive through mercenary service or by winning for themselves a new fiefdom. This was true of knights, nobles and princes – all ranks of the feudal aristocracy produced younger sons prepared to maintain rank through military force.

Opportunities were numerous. Civil wars were frequent. Competition for land and power kept the feudal aristocracy divided. The rulers of feudal states tried to control and channel these energies in wars of conquest – exporting the violence inherent in the system.

The dynamic of feudal imperialism was the drive to find booty and fiefdoms for a warrior caste otherwise liable to tear itself apart in fratricidal slaughter. It was this bloody logic that powered the Crusades.

“This land you inhabit is overcrowded by your numbers,” explained the pope. “This is why you devour and fight one another, make war and even kill one another. Let all dissensions be settled. Take the road to the Holy Sepulchre. Rescue that land from a dreadful race and rule over it yourselves.”

The war was sustained by lies. The Holy Land was supposedly desecrated with the blood of Christian pilgrims. Muslims were accused of revolting atrocities. Racist stereotypes appeared in contemporary art. In fact, Muslims, Jews and Christians had lived side by side in the Holy Land for centuries, and Jerusalem welcomed pilgrims from all three faiths. The truth was that the Crusades were an exercise in feudal violence and pillage. Most Crusaders returned home after the war. But they left behind four Crusader states – Edessa, Antioch, Tripoli and Jerusalem – and these, each guarded by just a few thousand men, had to be brutal to survive.

Living on stolen land and surrounded by potential enemies, the Crusaders were too few ever to feel safe. They needed wealth to recruit and maintain soldiers, and they grabbed it any way they could – attacking desert caravans, raiding their neighbours, and screwing the local peasantry. They were true robber barons.

The Arab response was slow. This seems at first surprising. The Crusaders were massively outnumbered, and Middle Eastern civilisation was greatly in advance of that of Europe. The Arabs boasted rich irrigation agriculture, sophisticated urban crafts, a dynamic banking system, and a strong tradition of scholarship, literature and art.

These were the fruits of the Islamic revolutions of the 7th to 9th centuries. Merchants and nomads from Arabia had united under the banner of Islam to create a vast Middle Eastern empire in which towns and traders could flourish.

But the urban classes did not control the Arab states – mosque and medina were subordinate to palace. Arab rulers siphoned surpluses into luxury consumption, political corruption and military competition.

The unitary empire of the early Islamic period had fragmented into numerous regional and local states. Economically stagnant and politically divided, much of the Middle East had recently fallen to Seljuk Turk invaders from central Asia. The Crusaders were battering at a crumbling edifice.

Few Arab rulers had the strength or will to resist. Many feared the upheaval and risks of all-out war. Some made alliances with Crusader states against their Muslim enemies.

It was the Second Crusade (1146–1148) that transformed localised resistance into full scale insurgency. The crusade ended in disaster and led to a decisive shift of power in favour of the architects of Muslim victory.

By 1154 Syria had been united under a regime openly preaching jihad – a holy war to destroy the Crusader states. By 1169 the jihadists had secured control of Egypt. And by 1183 the whole of Syria and Egypt had been united under the leadership of the famous Saladin.

Saladin has become a romantic and heroic figure, both in Europe and the Middle East. In fact he was a ruthless aristocratic politician as capable of lies and atrocities as any other. His famed magnanimity was carefully calculated.

Saladin placed himself at the head of the Muslim masses and raised a holy war against the Crusaders – he became the leader of a national liberation struggle fought under the banner of religion.

The tide was turned at the Battle of Hattin in 1187. Saladin assembled the greatest Arab army ever to face the Crusaders – 30,000 men, including heavy cavalry, swarms of light horse-archers, and thousands of jihadist volunteers.

The Crusaders were led in the ferocious July heat through a landscape in which the wells had run dry. Only when they were dying of thirst did Saladin engage. His huge host surrounded the Crusaders and plagued them with clouds of arrows.

Again and again the Crusaders charged, attempting to break out, only to be swamped by the huge numbers of their opponents. At the end of the day the survivors surrendered. The entire army of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem had been destroyed.

Saladin – in contrast to the Crusaders – spared most of his prisoners. The exceptions were understandable. With his own sword he slew Reynald de Chatillon, a notorious robber baron who had turned the caravan road beneath his castle at Kerak into a slaughterhouse.

And he ordered the mass execution of Templar and Hospitaller knights. These were the Waffen SS of the Crusades – warrior monks who waged a war of bigotry, hatred and genocide.

Jerusalem fell soon afterwards. The Third Crusade (1189–192) was mounted in response. Led by King Richard I of England – a boorish and brutal man under whose leadership the usual carnage and pillage prevailed – the campaign eventually reached stalemate.

Well handled, Crusader armies could hold ground and throw back even the strongest attacks – with their detachments of first class armoured cavalry, they packed the hardest punch.

But the Crusaders were too few to garrison fortresses and hold ground in the great sea of opposition that now confronted them. Even had they retaken Jerusalem, they could not have held it.

The Crusader states clung to patches of their territory into the late 13th century. Though Saladin’s empire collapsed on his death in 1193, the Crusader enclaves remained hemmed in by hostility and were unable to endure without external support. This never came.

Later Crusades were diverted by easy pickings and commercial advantage – the Fourth Crusade, for example, ended with massacre and pillage in the streets of Christian Constantinople. The last of the Crusader-held fortresses fell in 1291, almost exactly 200 years since the first Crusader army had reached the Holy Land.

In that time the Crusader states had contributed nothing – their rulers were backward robber barons who visited death, destruction and impoverishment on the people of the Middle East.

Neil Faulkner’s latest book Apocalypse is available.

Neil Faulkner Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated on: 10 February 2022