Lindsey German Archive | ETOL Main Page

From International Socialism 2:87, Summer 2000.

Copyright © International Socialism.

Copied with thanks from the International Socialism Archive.

Marked up by Einde O’ Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

The terrible election results which the Labour Party has suffered in the past 18 months are one of the great unspoken features of British politics today. The tame journalists and leader writers spend a day pondering why the results are so bad and then move on to the agenda which the spin doctors have conveniently drawn up for them. The Labour leadership has no interest in trying to highlight, let alone explain, why this should happen, and so continues to talk about Labour’s second term and how Labour remains ahead in the opinion polls. The most that happens is that dissident Labour figures plead for more attention to be paid to Labour’s ‘heartlands’ and ‘core support’ in the run-up to the next election. This lack of interest highlights the widening chasm between ‘official’ politics and what people are actually thinking and doing in their daily lives. For there now exists a crisis of representation in British politics which contains within it many warning signs for Labour. These include:

- A collapse in the morale of Labour supporters and activists which leads to widespread demoralisation, abstention from votes and even the switching of votes to electoral alternatives.

- Very low turnouts in polls which are differentially lower in strong Labour areas than in Tory or marginal areas.

- The haemorrhaging of Labour Party members in many areas.

- The decay of any Labour Party organisation or infrastructure.

- The decline in support for Labour inside its affiliated unions, where a growing minority are prepared to break from Labour to the left.

All of these questions deserve to be addressed in a more serious way than they have been in recent months. But they need to be looked at in a wider context than mid-term blues with a Labour government. These mid-term blues in fact follow a pattern under Labour governments. But the decline of the Blair government’s fortunes also marks a deeper crisis for Labour: the low point of its post-war organisational decline and an ideological turning point for much of Labour’s left.

A recent letter to a national newspaper from a London Labour Party member gives a sense of the crisis among Labour’s activists:

It is the Labour Party which really causes the heart to sink. My local party has lost about 300 members, or nearly a third of its membership. Several friends have resigned in sorrowful anger at the machinations, dishonesty, blatant nepotism, vapid statements almost immediately retracted – as on the North-South divide and GM foods – and sheer arrogance … foot soldiers still count more than pagers or focus groups in elections. Well, Blair bade farewell to vast numbers of his in London with his monstrous manipulations and attempts to bully people in the course of the Ken Livingstone mayoral debacle. [1]

This letter from Putney is one of many that have appeared in the press around the country. It is typical of the outpourings in the newspapers, at meetings and in discussions in the Labour Party itself over the past year. It speaks of the huge crisis in which Labour finds itself. To lose nearly one third of the members is bad enough, but to lose many of them over questions of policy and principle means that many of them will want to remain at least in part politically active, but cannot do so within the Labour Party. They are not just resigning into apathy. The results of their disaffection can be seen in every electoral contest over the past 18 months. The Scottish Parliament includes one Scottish Socialist Party member, Tommy Sheridan, and one former Labour MP, Dennis Canavan, who was rejected for selection as a candidate to the parliament by the Blairites, despite having a good record as a Westminster MP. Even worse results awaited Labour in Wales, where the Blair stitch-up of the selection of assembly leader to ensure the victory of Alun Michael over Rhodri Morgan led to the loss of a virtually assured Labour majority in the assembly and the victory of Plaid Cymru in rock solid Labour seats such as Islwyn and Rhondda. In London the results of the mayoral and assembly elections were even worse for Labour. Ken Livingstone won comfortably. His official Labour opponent, Frank Dobson, was soundly beaten by the Tory and was nearly pushed into fourth place by the Liberal Democrat.

But Labour’s rout went further than this. Massive numbers of Labour members refused to canvass, and Labour was forced to put out separate London Labour leaflets – one for the mayoral race, the other for the assembly with no mention of Frank Dobson on it. Labour lost two of the London assembly constituencies which it expected to win (Barnet and Camden, and Ealing and Southall) and so only had an equal number of seats to the Tories in the London assembly in a city which is overwhelmingly Labour. It also suffered massive losses outside London where council seats in Labour heartlands fell to the Liberal Democrats and the Tories. In London there was also a significant vote to the left of Labour with the Greens – in this instance clearly representing a left protest vote – winning three seats in the assembly after gaining Livingstone’s endorsement. In addition the vote of the London Socialist Alliance (LSA) was 3 percent across London, rising to 6 and 7 percent in two constituencies. In some parts of inner London the vote to the left of Labour stood at 25 percent.

It is a common defence from Labour’s leadership that the appallingly low turnout resulted from its supporters and core voters staying at home. Last year when Labour’s vote collapsed in the European elections, we were told that this was because of contentment – Labour voters simply could not be bothered to turn out because they were so happy with what the government was doing. Even the Blairites can no longer repeat this line with a straight face, especially since it is clear that, where there was an alternative motivated, Labour voters often did switch allegiances. As John Curtice pointed out after the election, Labour has a bigger problem than the Tories in getting its core support out. He argues on opinion poll evidence that ‘those who before polling day said they would vote Labour in the assembly election were, in the event, 5 percent more likely to have stayed at home than Tory supporters’. He goes on, ‘Among those who intended to vote Labour beforehand and who did go to the polls, only 77 percent actually voted Labour. In contrast, more than 90 percent of Tories stayed loyal to their cause.’ Curtice also concludes that ‘Labour’s vote did not fall most where turnout dropped most. Rather the opposite is the case. Labour’s vote fell most where the Lib Dems mounted their strongest challenges and in so doing motivated voters to come to the polls’. [2]

While it is of course true that any party in the mid-term of office can expect to suffer in local and regional elections, there are two features at work here. First, Labour is still relatively popular in headline opinion polls. Its results in various elections in the past year have been consistently worse than its poll ratings. Secondly, it clearly has a problem in motivating its core support and even its activists, which allows positive campaigning by anyone else to cost it votes. The reason why this occurs cannot wholly be found in the immediate crisis of Labour. Instead we have to look at the long term decline of Labour’s support and the connection between the disappointment of Labour policies and the weakening of its base.

Those who argue that Labour’s present problems are simply the result of a particular unfortunate set of politics and circumstances are missing the point. Every particular crisis or exodus of members from the party adds further to Labour’s long term decline and makes it harder for the party to recover. This has become particularly acute in the past 25 years, since reforms have no longer been on the agenda in the way that they were during Labour’s ‘golden age’. It is true that both major parties in Britain have suffered this long term decline, but Labour repeatedly finds itself at more of a disadvantage in this decline: its working class base is much harder to mobilise than the equivalent Tory loyalists. And the tendency for activists to be to the left of the Labour Party means that they are more likely to come into conflict with a Labour government than Tory supporters are with a Tory government. In any case, any study of Labour’s support since the war shows a near constant decline in membership and proportion of the vote.

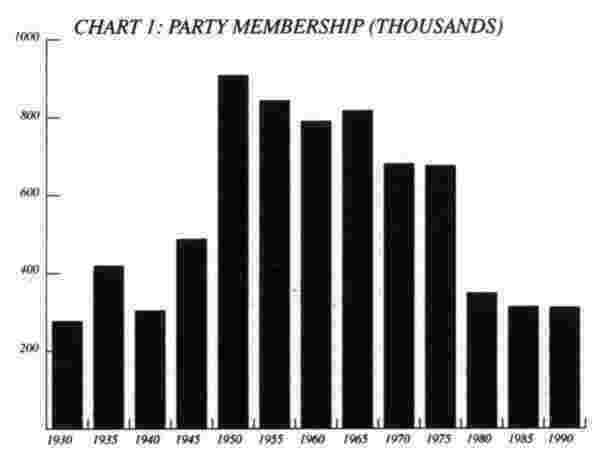

Labour’s high tide was the 1945 Labour government, responsible for shaping the post-war settlement which created the political consensus – full employment, welfarism and a mixed economy – that dominated the next 30 years. Labour’s share of the vote in 1945 was 48.8 percent, a figure matched again in 1951 (although in this election Labour actually lost to the Tories because of the distribution of seats) and even marginally surpassed in 1966, with 48.9 percent of the vote. [3] Labour’s membership also reached its peak at around this time. By 1950 it had 908,161 individual members – up from the 1945 figure which, although it suffered from the dislocations of wartime, was nearly half a million. In 1952 and 1953 individual membership stood at over 1 million before starting a slow but steady decline over the next two decades before accelerating in the 1970s and 1980s. [4]

The level of activism and involvement was relatively high in the early period after the war. Even then, however, Labour suffered what was to become a typical pattern of post-war governments: initial enthusiasm wore off relatively quickly as Labour failed to match its supporters’ expectations, leading to electoral losses. So the local council elections of November 1947 revealed a loss of support to the Tories. Labour lost 652 seats and 24 councils in England and Wales. While Labour had held its vote, the Tory vote increased. As the bosses’ magazine The Economist said at the time: ‘Austerity has awoken the middle classes from their apathy and made them politically active, while it has quenched the evangelical enthusiasm of the working class for “our government”.’ [5] This enthusiasm was certainly dulled by the mismatch between promises and delivery, even under this most reforming of Labour governments. A survey of planned and actual delivery of facilities carried out on 100 new housing estates in 1952 found that of 46 nursery schools planned only one had been built, of 33 health centres none had been built, and of 24 infant welfare clinics planned only 6 had been built. [6]

Despite the 1951 election marking the beginning of 13 years of Tory rule, Labour Party membership and organisation remained buoyant for most of that time. Labour retained a huge infrastructure of local newspapers and newsletters, offices and social clubs, agents, and affiliated organisations which had roots inside the working class in many localities. So the Romford, Hornchurch and Brentwood Labour Voice, a monthly Labour Party newspaper in Essex, could write of the 1951 defeat:

The Labour Party can be trusted to fight hard in parliament. Our task in the constituencies now is to keep up and improve our organisation and our propaganda; to be always ready for ‘the Day’, which cannot be long deferred. This Tory night can only be brief, and though the Tories will inevitably do some mischief, they cannot reverse the march of social progress. With the first light of dawn, they and their misdeeds will vanish. [7]

While the paper’s analysis was almost totally misguided – the Tories followed the post-war consensus and benefited from the economic expansion which raised living standards during the long boom of the 1950s, staying in office until 1964 – its existence and confidence pointed to substantial organisation on the ground. Labour filled a number of social and cultural functions in some areas as well. A report in the Labour Organiser in 1961 paints a picture which would seem unbelievable today:

A Labour space age club for 3–13 year olds that bulges at the seams – a Labour old people’s club that sits down 200 at its annual dinner. Those are at the two ends of Gateshead’s ‘Cradle to the Grave’ programme. And these are not proposals. They are live flourishing enterprises. To keep pace with its ‘new look’ the Gateshead Labour Party has provided the Young Socialists with their own coffee bar and independent meeting room. [8]

|

|

To compare Labour organisation in Gateshead now, and the extremely low turnout there and in other Labour strongholds of the north east of England, with this Labour Party, which attempted to organise and involve its members on a whole number of levels, is to begin to get some idea of how steep the decline has been. The sharp onset of decline began not – as might be expected – during the Tory years of the 1950s, but under a Labour government between 1964 and 1970, where Labour lost votes, activists and organisation.

Labour’s very narrow election win in 1964 and its decisive victory 18 months later in 1966 were greeted with enthusiasm. Labour’s programme was, as always, timid, and the party leadership subscribed to the view that Labour had to be modernisers if they were to win over more than their traditional supporters. But the party leader, Harold Wilson, was of the left and the expectations were that Labour would bring about real change after so long under Tory government. These expectations barely lasted past the 1966 election victory. Already it was noted that the turnout in 1966 was lower than in 1964, although still at 75.8 percent. In addition, while the Tory vote fell by 2 million compared with 1959, Labour’s only increased by 800,000. [9]

The government hit the rocks within a few weeks of being re-elected. It attacked the seamen’s strike, accusing its leaders of being Communists and creating great bitterness inside the working class movement. It was followed by the crisis over the pound which led to cuts in public spending and wage controls. This led to further unpopularity among Labour’s traditional supporters and the beginning of a sharp decline in membership and activity. A record of a Manchester Labour Party ward organisation shows how sharp this was. In Newton Heath average attendance in 1965 was 30 and total membership was 280. By 1967 average attendance was 18. In 1968 the average was 9. Total membership in the ward had more than halved by the late 1960s. [10] Overall, membership fell nationally from 817,000 individual members in 1965 to 680,000 in 1970. Labour’s share of the vote in the 1970 election (which it lost unexpectedly) fell from 48.9 percent in 1966 to 43.9 percent – a figure to which it never subsequently recovered. [11]

This decline and the failings of the Wilson government have to be seen against a backdrop of rising working class discontent and a growing radicalisation among young people. The loss of Labour members was over issues as diverse as the Vietnam War and Barbara Castle’s attempted introduction of the anti-union legislation, In Place of Strife. This led to working class protests against the Labour government and to a profound disillusionment with official Labour politics which propelled many of the most radical youth in particular away from any connection with the Labour Party. The high level of working class struggle continued under Edward Heath’s Tory government after 1970, which itself tried to introduce legislation attacking trade union rights. The anger welling up under Labour broke out between 1970 and 1974, leading to mass demonstrations and protests against the Industrial Relations Bill (later Act), the struggle to free the Pentonville dockers in 1972, two national miners’ strikes in 1972 and in 1974, all manner of other strikes over a range of issues including equal pay, and political radicalisation around a range of issues from student occupations to racism. By and large Labour failed to capitalise on these struggles and movements. Membership continued to fall and many of those newly politicised leapfrogged the Labour Party to join a number of the left wing organisations which had grown as a result of the events of 1968 and their impact on consciousness worldwide.

This partly continued the long term trend first noted in the 1950s: Patrick Seyd’s book, The Rise and Fall of the Labour Left, demonstrates how acute this problem was: in 1955 Labour’s NEC reported 45 constituency Labour parties with a membership of 3,000 or over – by 1977 this had fallen to six. In Bermondsey there were 4,689 members in 1952, but under 1,000 in 1977. Total membership of the three Lewisham constituencies in 1952 was over 16,000; by 1978 the then two constituencies had 4,000 between them. [12] To many active in the Labour Party now, even these lower figures would seem incredibly high – they testify how much Labour did have roots in the early post-war years compared with today. There is no question that here too the experience of Labour government in the 1960s played a key role in breaking up that support. In the space of four years – between 1965 and 1969 – Labour went from 60 constituency Labour parties affiliated with a membership of more than 2,000 to 22. Brixton Labour Party in south London suffered a catastrophic loss in the same period, from 1,212 members in 1965 to 292 in 1970. Brighton Kemptown halved its membership in those five years. There is evidence that much of this decline was due to disillusion among working class members, especially the manual working class – the ‘core vote’ which refused to be motivated by a Labour government that attacked workers. [13]

The Tories lost the 1974 election in the course of the miners’ strike and a Labour government was elected against a background of sharp class polarisation and after four years of major working class struggle. However, the share of the vote for Labour was disastrously low, both in February and again in October, when Labour stood again to win a bigger majority. It received 38.8 percent and 36.7 percent respectively, whereas the Liberals picked up many votes, scoring just under 20 percent. [14] Although Labour began to recruit people again in the 1970s, and one writer says that Labour probably had more members in 1980 as individuals than it had in 1970 [15], the long term decline continued. The membership figures never recovered overall from the fall of the 1960s. Seyd points to the sorts of people who joined in the 1970s: higher educated, public sector employees, working class militants and feminists. [16] Few of them had reason to support the Wilson-Callaghan governments which succeeded the Tories. The high hopes of the early 1970s were turned sour as the unions were brought back onside through the Social Contract, and where the government presided over high unemployment, falls in working class income and severe public spending cuts, while also ushering some of the worst reactionary ideology in areas such as education and the family. The relatively high working class unity of the first part of the decade turned into bitter divisions among the working class, with scabbing sanctioned by the trade union bureaucracy in a number of disputes. Little wonder that the government collapsed in ignominy in 1979 against the background of working class struggle pitched in headlong opposition to it.

Divisions between left and right in the Labour Party had always been there, but had become more acute in the course of the 1970s, with disputes over issues such as deselection of MPs (the case of Reg Prentice, the right wing Labour MP for Newham north east, who was deselected allegedly by the new middle class membership which had parachuted into various working class constituencies and was trying to draw Labour to more extreme left wing views, was one of the best known). The left outside parliament began to get better organised: in the late 1970s, for example, 18 local Tribune groups were established round the country. [17] But with the victory of Thatcher in 1979, all the divisions inside Labour came to the surface and the left was in the ascendant. The argument that Labour had thrown away its years in government by attacking its working class supporters had a resonance. So too did the argument that being inside Labour was the only way for the left to effect change. The movement around Tony Benn which culminated in his contest for deputy leader in 1981 brought into the party and into activity many activists and left wingers, some disillusioned with working in left wing groups throughout the 1970s and seemingly getting nowhere.

Bennism was the high tide of the post-war left and the chance to reverse the decline in Labour’s membership and the fortunes of its activists. Although it held out this promise, it was not to happen. By 1980 party membership stood at 348,000, almost half that of a decade earlier. [18] Partly the rise of Bennism polarised the party even further with the right-wingers around the Gang of Four splitting to form the SDP in 1981. More importantly, although the left came close to winning Tony Benn as deputy leader, this represented the high tide for the left and it was afterwards under a series of attacks. These attacks were compounded by Bennism’s organisational weakness. In particular, it did not have roots inside the union rank and file which could have helped to resist the attacks. The party leadership was able to set in motion a series of attacks and witch-hunts on the left throughout the 1980s which undercut what base Bennism still had and demoralised another generation of activists. Even in the early 1980s Michael Foot placated the right by denouncing Peter Tatchell, a left winger who was the official Labour candidate for the Bermondsey by-election. Foot also started the witch-hunt against Militant.

The leadership could not have been successful, however, without the political weaknesses of the left themselves. The left retreated into its stronghold – local government. In the early 1980s Bennites and others on the left controlled a number of councils including the Greater London Council, Lambeth, Liverpool, Islington and South Yorkshire. It was here that they would build a base and challenge the Tory government to defeat them, and here that they would revitalise the Labour Party. It didn’t happen. There were key points in the retreat of the left. One was the refusal to fight the Tory government over its ratecapping policy in 1985. The GLC under Ken Livingstone moved to comply in March 1985, to be followed by all the ratecapped authorities. The left’s local government stand had failed, and with it went the further decline of activism on the ground. Patrick Seyd describes it thus:

By now many left wing councillors had become disillusioned with local government: their radical commitments had been undermined by central government pressures, electoral necessities, bureaucratic hostility, or Labour Group power politics. Others had tempered their political ideals to the practical necessities of administration. Some councillors withdrew, politically and personally exhausted by the struggles, whilst others were moving on from Sheffield to Westminster politics. [19]

The result of the 1980s was a much bigger intake of local government left MPs by 1987, who adapted very quickly in most cases to the demands of the leadership – David Blunkett and Margaret Hodge were two examples. Local parties were often left effectively leaderless as a result of expulsions of key activists in localities and the abandonment of the field by many more.

Neil Kinnock, Labour’s leader from 1983 to 1992, saw one of his main aims as crusading against the ‘hard left’ inside the party, despite having come from the left himself. This was done in the name of ‘making Labour electable’ although Kinnock himself was singularly unsuccessful in this and was credited with being an electoral liability in 1992. He set out to witch-hunt Militant from the Labour Party. In this he was, however, partly successful. He regarded the year long miners’ strike in 1984–1985 as a setback on the path to Labour Party modernisation and used the 1985 Labour Party conference to make a speech attacking Militant in Liverpool. The Militant-led council was coming to the crunch about setting a rate. Kinnock used the image of the left as unconcerned with the practicalities of people’s lives, concerned only with grand gestures:

I’ll tell you what happens with impossible promises. You start with far-fetched resolutions. They are then pickled into a rigid dogma, a code, and you go through the years sticking to that, outdated, misplaced, irrelevant to the real needs, and you end up in the grotesque chaos of a Labour council hiring taxis to scuttle round a city handing out redundancy notices to its own workers. I am telling you, no matter how entertaining, how fulfilling to short term egos – you can’t play politics with people’s jobs and with people’s services or with their homes. [20]

The speech caused uproar but since the struggle against ratecapping was going down Kinnock was able to use that, plus the miners’ defeat, to press home his advantage against the left. He adopted the policy of the ‘dented shield’, which argued it was better to run local government on the Tories’ terms than not to run it at all. The consequence was major cutbacks, retreats and defeats as Labour councils accepted more and more limiting terms. This as much as anything led to further demoralisation and passivity from Labour supporters who could no longer make a difference in local government. It also meant that, when Thatcher’s greatest disaster, the poll tax, was introduced in 1989 and 1990, Labour’s official policy was extremely timid and didn’t really oppose it. Building demonstrations against it was by and large left to those outside the Labour Party.

The defeat of the miners coupled with the defeat over ratecapping also led to a polarisation on the left of the Labour Party which meant further demoralisation. Many made their accommodation with the leadership and abandoned any hope of changing anything while others continued on the path which the Bennites had mapped out in the early 1980s. The defeats of 1987 and again of 1992 led to renewed debate about whether Labour should continue to ‘modernise’ and abandon its traditional policies or whether it should be much bolder in putting forward socialist ideas. Those advocating the latter were increasingly in a minority and even many erstwhile left wingers decided that it was worth compromising in order to win an election. This was the path followed after 1992 when the extremely cautious ideological right winger John Smith won the backing of many former left wingers, and when Tony Blair encountered relatively little opposition in his abolition in 1995 of Clause Four of the party’s constitution, the paper commitment to nationalisation. A sign of how far some of the old ‘soft left’ had travelled in this process can be seen from the chair of the Labour Co-ordinating Committee, once a left body, now a slightly critical cheerleader for Blair, who wrote in 1995:

But the culture of betrayal will only be finally banished if Labour now seizes the moment to both clarify its project and solidify support for this in the Party ... No one should be under any illusion that the easy victory at the April special conference reflected whole-hearted endorsement of the Blair agenda by the great bulk of party activists ... A chasm now exists between the 100,000 new members Labour has recruited in the past year and the many activists who run the party at local level. The new members not only embrace the change – they may even have joined because of it. Whilst many of the traditional activists, by no means hard left sympathisers, were at best ambivalent ... Labour’s cultural revolution is still only at its early stages. It is still a long way from becoming the participatory, empowering, listening, campaigning party which might attract people in large numbers to become actively involved in the politics of change. [21]

In the early 1990s the modernisers and Blairites set massive store in building this sort of mass campaigning party to which they could appeal directly without the bother of having to go through the party structures. Certainly, in the early years of Blair’s leadership he had some success in appealing to those with no ideological backgrounds in the labour movement to join. He argued in 1995, ‘We have increased our individual membership by 120,000. By the next election over one half of our members will have joined since the 1992 election. It is literally a new party.’ Patrick Seyd estimated that when Blair became leader in 1994, membership stood at 265,000 and that by the election in 1997 it was around 400,000 – an increase of 140,000. But rapidly people also began leaving Labour. [22] The truth is that Labour is further away today from building such a party than it was five years ago. The latest estimates put Labour’s membership at 350,000 – a loss of 50,000 since the election. [23] The new passive members have proved to have retained less loyalty to the party than might have been expected and those old activists who remained have found themselves increasingly disillusioned with prospects for change.

This was quite predictable, because in reality there was not such a distance between the two in terms of ideas and values. For instance, a lot of the new members were working class, even though the proportion of trade unionists went down. The Labour Party has also remained the party of the poor. In 1998 nearly a quarter of all Labour members were on incomes of £10,000 a year or less. Therefore the attitudes of the ‘New Labour’ members are not in most areas fundamentally different from those of Old Labour. But the organisational links with the new members are much weaker, with new members less likely to do even the more passive activities in supporting Labour at election times, such as displaying window posters or donating money. [24] Patrick Seyd argues that this leads to a fundamental weakness at election time:

For a party to be successful it has to offer incentives to its activists. The activists go out and do the recruiting, canvassing and encourage others to join. But if you create a party that bypasses the activists, which I think the Labour Party has done over the past ten years, those incentives disappear. The Labour Party does have very strong vertical communication between the Labour leadership and party members. But it also needs horizontal communication – people in the same street or area who go along to their friends and remind them to vote. That communication is very weak. [25]

Blair has proved a failure in attempting to build a mass party without roots, appealed to through the media and the spin doctors. The plan to double the membership never came to fruition and now membership seems on all anecdotal evidence to be falling. Even worse, he has succeeded in destroying many of the roots that Labour did have and taking the long term crisis of membership and activism which Labour has suffered onto a new plane.

Labour’s 1997 election win was widely welcomed and confounded the expectations of Labour’s leadership in its scale. But the size of the landslide hides a multitude of sins. Labour’s vote was in fact relatively low: ‘First, at 44.4 percent, Labour’s share of the vote was lower than it had achieved in all elections from 1945 to 1966, including the three it lost in a row in the 1950s. Second, with the turnout across the United Kingdom as a whole at a record post-war low of 71.2 percent, only 30.9 percent of the electorate voted for the new government’. [26]

The weaknesses of Labour’s general election performance have only been exacerbated by events since. The experience of the recent elections show low turnout, higher than average Labour abstention, especially in Labour strongholds, and demoralisation of many activists. The leadership’s behaviour in the selection process for elections in Scotland, Wales and London has caused much dismay and bitterness, and has had the effect of leading at least some activists to consciously decide not to help Labour get elected. The commonsense view at Millbank and in Downing Street is that this does not matter and that elections are not won or lost by the activists. But there is much evidence to the contrary – consciously arguing and campaigning for a particular party can make a real difference in certain localities. [27] In 1997 it was found that Labour members were more confident: ‘A quarter of Labour voters reported that they encouraged others to support their party; only one-tenth of Conservative supporters did so.’ [28] The activity on the ground can make a big difference to Labour. In this context, the debacle over selection, especially around Ken Livingstone, can only have had a very harmful effect. It does not simply mean that Labour activists are fed up with the leadership and the apparatus. It also means Labour has squandered its most precious resource – and it is finding this resource increasingly difficult to replace.

There are, of course, different responses to the demoralisation of Labour’s activists. The government’s is to throw a few sops before the next election, especially over pensions where Labour’s miserly policy has caused great anger and allowed them to be outflanked by the Tories. Many of those who opposed the government over Livingstone or over the Scottish and Welsh parliaments are keen to paper over the cracks, to use the discontent inside Labour to extract further concessions from the Blairites, hoping that Labour can be revived again. This is the view put by Paul Flynn in his book about the Welsh stitch-up, Dragons led by Poodles, and is also the view of the majority of the left which is still in the Labour party. [29] Here the key campaigns focus around getting Livingstone back into the Labour Party. Yet this approach misses the whole point about the cumulative disillusion among Labour activists: it comes from Labour’s repeated failure to deliver anything which can meet the aspirations of its supporters. For nearly two decades now, Labour activists have been told to swallow successive abandonment of policies in the interests of getting Labour elected. Now, with the biggest Labour majority ever, they are being told they still have to accept the policies they had always fought against. For a substantial number of Labour activists this is too much to stomach and they are turning their backs on Labour. These are not just passive Labour voters – they are people who have been councillors, local Labour party officials, key people in holding organisation together during long and difficult years. They have devoted 20, 30, 40 years to the Labour Party and they now feel that they do not have a political home.

This is often a personal tragedy for the individuals but their dilemma is made easier by two things: the right wing nature of Blairism, which is pushing people away from Labour, and the increasing recognition on the left that there is life outside the Labour Party. The growing mood of resistance around issues such as asylum seekers, job losses in the car industry or the privatisation of council houses, plus the votes for the left in Scotland and Wales and now with the LSA, means that for the first time in many years socialists find that they are saying things which have an echo with much greater numbers of people than the organised left. The pressure from both sides means that it is possible to talk about building a socialist alternative outside Labour and find a resonance among a significant minority inside the working class.

Blairism has severely weakened Labour. There is a major crisis of cadre inside the party as those who have traditionally carried the arguments of the party lack the motivation to continue to do so. Although some of the cadre can in theory be won back to doing so, there is no obvious reason why they should be, given their lack of sympathy for the Blair project. The weakening of the cadre worsens the long term decline of organisation inside the Labour Party, and the experience of the 1960s and 1970s suggests that that can never be totally recovered. Labour’s lack of organisation in its traditional strongholds is now a serious problem, especially in a closely contested election. Finally, recent elections have demonstrated that there is a weakening loyalty to the Labour vote. In some parts of London almost a quarter of all voters in the assembly election voted Green or LSA, ie to the left of Labour. Once formerly loyal voters make this jump, it is harder for Labour to pull them back in subsequent elections.

Labour has traditionally depended on the union leaders to deliver money, votes and support for its policies and it is still able to turn to them, however critical they are of Blairism. But the hostility to Labour’s leadership from the rank and file is growing – as witnessed by the overwhelming union votes in London for Ken Livingstone. After the selection fiasco an important minority in the unions wanted to back left alternatives such as the LSA, and calls to withhold the political fund to Labour have been growing. Increasingly the experience of council workers, health workers and local government workers is of having to confront Labour councils and a Labour government to achieve their aims, and this also weakens the bond between the unions and Labour. Such discontent makes the national officials even more reluctant to rock the boat, fearing as they do revolt from below more than anything else, but it is increasingly the case that Labour is having to rely on these officials to keep the lid on working class discontent. So far this has often been successful, but Labour is now acting increasingly without the safety valves which kept so many working class militants loyal to it. The absence of safety valves means that there is also often an absence of organised expression of discontent. The other side of this is that the Labour and trade union leaders have little or no warning of when explosions are likely to occur.

The weakening of Labour’s base, the demoralisation of its cadre and the breaking of many good militants from ‘their’ party present huge and exciting opportunities for socialists. Increasingly those who want change are finding that they have to look for it outside of Labour, and this raises in concrete form the urgent task of building a real socialist alternative.

1. Letter from R. Knowles in The Independent, 6 April 2000.

2. J. Curtice, Heartland Blues, The Guardian, 8 May 2000.

3. Figures for share of the vote given in K. Laybourn, A Century of Labour (Stroud 2000), p. 158.

4. Figures for membership, ibid., p. 159, and P. Seyd, The Rise and Fall of the Labour Left (London 1987), p. 41.

5. See S. Fielding, P. Thompson and N. Tiratsoo, England Arise (Manchester 1995), p. 175.

6. Ibid., p. 106.

7. From the Labour Party Archive, quoted in S. Fielding, The Labour Party: ‘Socialism’ and Society since 1951 (Manchester 1997).

8. From Labour Organiser 40:464, quoted in S. Fielding, op. cit., p. 64.

9. Quoted, ibid., p. 78.

10. Quoted, ibid., pp. 80–81.

11. See figures in K. Laybourn, op. cit., pp. 158–159.

12. P. Seyd, The Rise and Fall of the Labour Left (London 1987), p. 42.

13. Ibid., p. 43.

14. K. Laybourn, op. cit., p. 158.

15. G. Hodgson, Labour at the Crossroads (Oxford 1981), p. 57.

16. P. Seyd, op. cit., p. 44.

17. Ibid., p. 82.

18. K. Laybourn, op. cit., p. 159.

19. P. Seyd, op. cit., p. 157.

20. Quoted in S. Fielding, op. cit., p. 131. I was at the conference where Kinnock made the speech and it was absolutely electric, dividing the conference down the middle.The gatherings then were incomparably more left wing then than they are today and although the left was in decline it still had considerable conference strength.

21. From Labour Activist, June 1995, quoted in S. Fielding, op. cit., p. 150.

22. See Whose Party Is It?, Interview with Patrick Seyd by Martin Smith, Socialist Review, July/August 1998, p. 14.

23. The estimate is based on a survey by Patrick Seyd and Paul Whiteley reprinted in The Independent, 30 May 2000.

24. M. Smith, op. cit., p. 14.

25. M. Smith, op. cit., p. 14.

26. D. Butler and D. Kavanagh, The British General Election of 1997 (London 1997), p. 295, appendix by John Curtice and Michael Steed.

27. See P. Whiteley and P. Seyd, Grassroots Gains, The Guardian, 8 March 2000.

28. D. Butler and D. Kavanagh, op. cit., p. 238.

29. P. Flynn, Dragons led by Poodles (London 1999).

Lindsey German Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 31.5.2012