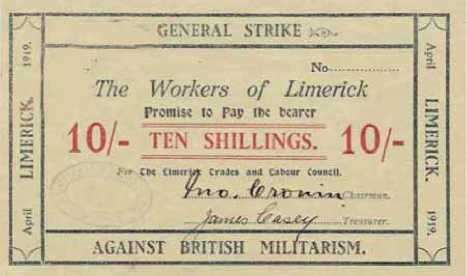

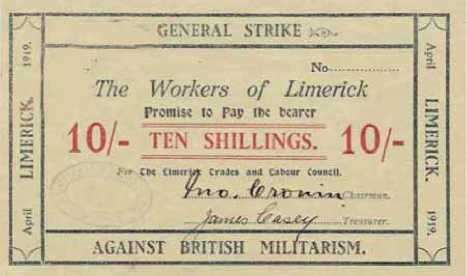

10 Shilling note issued by the Limerick Soviet

Conor Kostick Archive | ETOL Main Page

From Irish Marxist Review, Vol. 4 No. 14, November 2015, pp. 18–28.

All links have been checked and modified where necessary. (July 2021)

Copyright © Irish Marxist Review.

A PDF of this article is available here.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

In the coming centenary commemorations of the Easter Rising of 1916 there will be a great deal of enthusiasm for the efforts of that generation to escape the British Empire. Yet nearly all the public attention and memorial events will be directed to discussion of the role of the senior figures of the national movement. One of the most neglected groups in the social memory of these years was the working class. Yet it was working class action above all that stymied British authority in Ireland. In the revolutionary period of 1918 to 1923, Irish workers made an enormous contribution to the fact that Britain lost its ability to govern the country. More, they created moments in which an alternative to partition emerged, moments where it seemed like Ireland might follow Russia in becoming a republic governed by soviets.

The argument that Ireland was too rural to have been able to experience a social revolution at this time – too dominated by the church and the outlook of a conservative peasantry – is refuted by a close look at the evidence. Near constant class warfare existed on the land in these years. In the east, where most of the land was held by large farmers and worked by a rural proletariat, there were the most extraordinary scenes and battles involving the derailing of trains, as rural workers fought for higher standards of living. There were also scenes reminiscent of the Great War, in which red armies of rural workers battled white armies of the FFF (Farmers Freedom Force). In the west, where great tracts of land were still owned by absentee landlords, the struggle took the form of small farmers breaking up the large estates or in some cases appropriating them collectively and working them as soviets. [1]

Yet, of course, it was in the urban centres that the working class displayed the greatest militancy and in addition to an almost continuous sequence of strikes and local general strikes there were five crucial turning points in these revolutionary years created by urban working class activity: firstly, a general strike against conscription; secondly, a general strike at the beginning of 1919 in Belfast; thirdly, the Limerick Soviet of April 1919; fourthly, in April 1920 a soviet takeover of the major towns of Ireland for the release of hunger strikers; and fifthly, throughout 1920, the refusal of transport workers to move British troops or army equipment.

On 16 April 1918, with the passage of the Military Service Bill by 301 votes to 103, conscription was brought to Ireland. The plans of the War Cabinet, however, failed disastrously and not one Irishman was dragged off to the trenches. Instead, the issue of conscription was a tipping point. It brought the country to its feet. And if readers in the Republic today feel that the issue of the water charges is doing something similar, you can imagine how the much more life-and-death issue of conscription in 1918 galvanised the population.

Crucially, workers entered the conflict as a class and much to everyone’s astonishment, including their own, proved themselves to be an enormously powerful force. A general strike against conscription took place on Tuesday 23 April 1918, with work all over the country suspended. A ban on marches for the day from the British authorities proved unenforceable and almost every town, especially in the 26 Counties, had its own march, usually organised by the local Trades Council. The overall success of the day’s action was acknowledged by the Irish Times, which stated that ‘April 23rd will be chiefly remembered as the day on which Irish Labour realised its strength.’ [2]

The protest not only registered the massive opposition to conscription that existed in Ireland, it precipitated an upsurge of popular activity both on the national and social question. Workers’ confidence took a great leap from the success of the action, which had drawn in hundreds of thousands of workers who had never been involved in a strike before. The success of the strike against conscription brought a spurt of growth for the Irish Transport & General Workers Union in particular and a rise in the combativeness of workers: the number of strikes doubled compared to the previous year. The number of new branches registered for the Transport Union leapt from an average of two a month in 1917 to around twenty a month for the second half of 1918. [3]

Having identified this moment as one in which Irish workers began a new phase of radical militancy, it is also important to identify too that at the very outset of a surge in Irish working class militancy, the leaders of the Dublin-based trade unions adopted a disastrous political strategy that was in part responsible for allowing Unionism to succeed in portioning Ireland. For the labour leaders took the decision to participate in a catholic and nationalist opposition to conscription, rather than lead the movement in a secular direction that sought to include protestant workers.

Northern workers who had been persuaded to fight for King and Country had by now experienced four years of war. Terrible years, which had marked every family. The Battle of the Somme in July 1916 had been something of a turning point in terms of Loyalism. On 1 July 1916, the 36th (Ulster) Division – formed largely out of members of the Ulster Volunteer Force – threw itself into German machine-gun and artillery fire, doing remarkably well, only to be forced back with 5,500 casualties. The leaders of Loyalism did their best to present the battle as a glorious moment in Ulster history, ‘the record of the Thirty-Sixth Division will ever be the pride of Ulster’, said Winston Churchill. Rather, it was the heartbreak of Ulster and no wonder when conscription was introduced for the whole of Ireland that northern workers, including members of the UVF, attempted to join the opposition. In Tyrone, UVF members even offered to become members of the IRA in order to fight conscription. [4]

The problem that these former loyalists had is that southern labour leaders had thrown their lot in with a specifically catholic opposition to conscription. Tom Johnson and William O’Brien, the key figures in the ILPTUC, were appointed to a ‘National Cabinet’ steering committee for the anti-conscription campaign. There they were joined by Arthur Griffith and Éamonn de Valera for Sinn Féin and John Dillon and Joseph Devlin for the Irish Parliamentary Party. There too, they went along with an appeal by the committee to the catholic bishops of Ireland, which resulted in a clerical manifesto against conscription to which Johnson and O’Brien put their names.

Where did this leave protestant workers who – in their thousands – were looking for an alternative to Orangeism and Unionism? Only with an opposition to conscription that seemed to point towards the establishment of a catholic state over Ireland. This approach by Ireland’s trade union leaders, of attempting to be the left flank of catholic nationalist Ireland, was also evident in the 1918 elections. On that occasion Labour stood aside in favour of Sinn Féin candidates. For historians of the Socialist Party tradition, this moment was the critical one for the entire future of the Irish left in the revolutionary era. For them, the failure of Labour to win the electoral leadership of the country in 1918 marks the turning point of the Irish revolution. [5] Certainly, there was a problem, particularly for northern trade unionists, if their colleagues in the south were associating closely with Sinn Féin rather than advocating independent working class demands. But the Socialist Party has always exaggerated the importance of electoral activity. The real turning points of the period were not electoral ones but the outcomes of the incredibly radical mass movements of workers against opponents ranging from the British authorities to Irish employers and landowners.

The 1919 general strike in Belfast was the next major intervention of Irish workers in these years and it arose out of a crisis in the city at the end of the war. There unemployment had risen sharply with the return of thousands of soldiers. As a result, the demand was raised by the city’s trade unions that the working week be reduced to 44 hours from 54 and that the employers utilise the extra hours to provide jobs for the returned soldiers. When an overwhelming vote in favour of the strike became known, impatient power station and gas workers struck on Saturday afternoon 25 January 1919. The first response of the shipyard owners was to try to continue work despite the strike, using foremen and apprentices to keep the yards open. But a spontaneous picket of 2,000 strikers broke through the gates and brought out the apprentices, before stoning the company offices for good measure. By nightfall the strike committee was in control of not just the power supply of the city but the streets. No traffic could travel down Queen’s Road, for example, without a pass issued by them. [6]

The correspondent for the Manchester Guardian sent the following report: ‘Soviet’ has an unpleasant sound in English ears, and one uses it with hesitation; but it nevertheless appears to be the fact that the Strike Committee have taken upon themselves, with the involuntary acquiescence of the civic authority, some of the attributes of an industrial soviet.’ [7] The Mayor of Belfast admitted ‘as far as the municipal undertakings were concerned [he was] entirely at the mercy of the strike committee.’ [8] A telegram from the Belfast authorities confirmed the situation, that small businesses were having to contact the strike leaders, ‘The workmen [sic] have formed a ‘soviet’ committee, and this committee had received 47 applications from small traders for permission to use light.’ [9] It is noteworthy that the strike committee consisted of both protestant and catholic trade unionists, with a catholic, Charles McKay, at the head of a strike in which protestant workers were the majority.

The same Monday that the strike began, the British Government announced that it was going to introduce the eight-hour day for railway workers. This was to head off possible solidarity from railworkers for the engineering strike that was also taking place in all the major British cities, and most militantly in Glasgow. In Belfast the news did not prevent railworkers unofficially joining the strike on Tuesday 28 January. Other groups of workers joined the movement. Graveyard workers, also without the sanction of their union leaders, walked out to participate in the strike. In the rope factories, the mainly female workforce learned that pickets were due to arrive to bring them out, and they too struck on their own initiative. Meanwhile at the Sirocco engineering works some strikebreakers and apprentices were managing to keep the factory open. This was dealt with by cutting off the power to the factory. In the evening theatres were now closed, while few restaurants and hotels could manage a service. The dark streets of the city were thronged all the same, with excited crowds of workers defying the arrival of snowy weather.

By Thursday momentum was still gathering. A rent strike began in working class districts. In Royal Avenue and North Street, more plate glass windows were put in to prevent employers draining power allocated for emergency services. [10] A major turning point in the fortunes of the strike came on 4 February 1919 when the transport workers sent a deputation to the strike committee and asked to be included in the action. The leaders of the strike were nervous of taking a step that would result in a major escalation of the dispute. As J. Milan, of the Electrical Trade Union told the Newsletter, ‘the strike committee adopted a policy of procrastination on the matter ... the transport workers would come out at any time but they hadn’t called on them as the strike committee wasn’t sure it could run the city.’ [11] At angry meetings the rank and file strikers demanded that the transport workers be brought out, and that the ‘up-town’ shops (Mackie’s, Combe’s, Sirocco and the Linfield foundry) join the strike also. But bombarded by newspaper scare stories about how food supplies would give out if there were further escalation, the strike committee lacked the resolve to escalate matters further and put to the vote a proposal to accept a 47 hour working week. Surprisingly the result of the ballot went against the strike committee on Friday 14th February by 11,963 votes to 8,774. [12]

Sensing a weakening of the strike, however, the authorities now made their decisive move and the next day sent in troops that had been called up from Dublin. These soldiers guarded the power stations and trams. Attempts to move the trams were met with running battles from mass pickets. [13] The strike committee refused to implement the decision of a mass meeting held on Custom House Square on Sunday to call out the transport workers at last. But the rank and file workers had failed to develop any organisational structures independent from the strike committee, and although they expressed their anger and frustration at the committee outside of the hotel where talks were taking place with the employers, the engineering factories were now reopening. A gradual drift back to work took place over the next two weeks until on 24 February 1919 the strike was officially ended. Belfast’s greatest working class struggle was over, and although they did not know it, the leaders of the national movement in the south had seen a significant turning point pass in their own campaign.

The leaders of Sinn Fén had no interest in this strike. This was natural enough from those on the right of the party, such as Arthur Griffith, who were hostile to independent labour organisation, but even the socialist.inclined Minister for Labour, Countess Markievicz, who at the time was giving fiery speeches in favour of the Workers’ Republic [14], had no familiarity with northern working class politics. At no time did Sinn Féin have a strategy for incorporating the north into their struggle for independence. This can be seen from their eventual adopting, in July 1920, an economic boycott against northern business, which Arthur Griffith believed ‘would bring the unionist gentlemen to their sense very quickly.’ In fact, the Belfast boycott reinforced the prospect of partition as although it caused an estimated loss of £5million of trade, it proved to northern business they could get by on their connection to the markets of the British Empire. [15]

Outside of the nationalists in the north, the only constituency that might have been sympathetic to the idea of Irish independence were the more militant protestant workers, who saw the Unionist shipyard owners and employers as their greatest enemies. For over two hundred years there has been a radical, non-sectarian, protestant tradition in the north, and in 1918 it was most strongly represented in the form of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and other revolutionaries such as those behind the newly created Revolutionary Socialist Party of Ireland, which in 1919 was holding meetings in Belfast of up to 500 people. [16] In the heightened atmosphere created by the strike for shorter hours, the Belfast left found itself with a large audience. They organised the city’s biggest ever demonstration, that of May Day 1919 when over 100,000 people marched from Donegal Place to Ormeau Park. The organising secretary was Sam Kyle, whose speech on the day emphasised the Red Flag, internationalism, and the need for Belfast to have independent labour representation. [17] In the subsequent local elections of January 1920 these activists won an impressive 12 of the cities 60 seats; the most remarkable result being that of Sam Kyle who stood in Shankill and topped the poll. Since this was an election that took place under the newly introduced PR system it is possible to prove that his supporters understood that his politics were hostile to unionism, as only a tiny percentage of his transfers went to unionist candidates. [18]

Nevertheless, the influence of the left over the wider working class was on the wane. The partial defeat of the strike led to demoralisation spreading through Belfast’s working class, and at the same time a sudden slump in May 1920 combined with the continuing existence of a large number of unemployed ex-veterans to create the conditions under which a sectarian pogrom could take place. That July, the leading Unionist politicians, such as Edward Carson and James Craig used the orange marches to make speeches advocating an attack on Labour and Sinn Fein. [19] Loyalists, with the complicity of the shipyard owners, then organised meetings where several thousand unemployed and ex-servicemen gathered to roam through the factories armed with sledgehammers and other weapons. Catholics and socialists had to flee for their lives. About 12,000 workers in all lost their jobs, to be replaced by the loyalists; some 3,000 of those were protestant trade unionists. [20] Ex-Orange Lodge master, turned Larkin support, John Hanna, was one of these. In his view, ‘during the strike for 44-hours week the capitalist classes saw that the Belfast workers were one. That unity had to be broken, it was accomplished by appeals to the basest passion and intense bigotry.’ [21] The mobs also went to Langley Street and burnt to the ground the hall of the ILP, ‘and as a result the growth of the Labour movement was stemmed.’ [22]

With the crushing of radical organisation in Belfast, and the decision of the British Cabinet on 8 September 1920 to raise a Special Constabulary, which absorbed the Ulster Volunteer Force into an official security force, the core structures of a future partitioned Northern state were secure.

The hold of the British authorities over the rest of Ireland had been steadily weakening throughout 1919, despite increasingly drastic repressive measures, such as the deployment of the notorious ‘Black and Tans’ in the autumn of that year, and the declaration of martial law in more and more parts of Ireland. It was the impact of military rule in Limerick that led to the largest soviet of the period, that which took over the running of Limerick City on Sunday 13 April 1919. [23] There, General C.J. Griffin had declared the city and part of the county a special military area. In particular, he deployed troops onto the bridges over the Shannon and insisted that everyone needing to cross the bridges apply to him for a pass. To obtain a pass a letter had to be forwarded from an RIC sergeant. The costs of the extra policing were to be levied on the rates. These measures were designed to prevent known republicans from moving around the area, but they were too sweeping and crude to be effective, angering almost the entire local population.

After a twelve-hour discussion as to their response to Griffin’s initiative, the local Trades Council took the unanimous decision to call a general strike. They had discussed the implications of their action and immediately set up committees to take charge of propaganda, finance, food and vigilance. [24] The reaction from Limerick’s workers was overwhelmingly supportive. Soon water, gas and electricity supply was in the tight control of the committee, who were quickly referred to as the ‘soviet’. Work was allowed to take place at bacon and condensed milk factories, but the bakers and Cleeves’ creamery workers walked out anyway to join what was becoming a carnival atmosphere. In all, 14,000 workers were on strike. Large crowds gathered and moved through the city, discussing events. [25] The local RIC telephoned Dublin for at least 300 more reinforcements but Deputy Inspector-General W.M. Davies replied that this was impossible as ‘there are so many strikes going on elsewhere.’ Eventually 50 RIC were sent and permission granted to have military support. [26] Not that crime was the force’s concern. During the two weeks of the soviet no looting took place nor a single case arose for the Petty Sessions [27]

The first priority for the soviet was to secure food supplies for the city’s 38,000 inhabitants. A panic over the possibility of scarcity was encouraged by Dublin Castle who issued a communiquedenying responsibility for any lack of the necessities of life. [28] The strike leaders responded by asking the bakers to resume work and fresh bread was thereafter made available in the mornings. A few delegated shops were given permission to open and sell foodstuffs, but only at prices set by the soviet. These prices were put on posters and placed around the town. More radically still, the soviet decided to expropriate 7,000 tons of Canadian grain that was at the docks. They also set up four depots to receive food from farms outside the town.

Because the creamery was closed, there was in fact no shortage of fresh milk at the usual price. Workers also smuggled food into the city past the military with relays of boats and even in a funeral hearse. [29]

As money began to fall into short supply, the soviet rose to the occasion once more, and set up a sub-committee, mainly consisting of the clerical workers from Cleeves’, to oversee the printing and issuing of its own currency, which came out in one, five and ten shilling notes. A list of shopkeepers and merchants who would accept the new currency was posted around the town. [30]

10 Shilling note issued by the Limerick Soviet |

On Wednesday 16 April 1919 the dispute looked as though it was about to escalate drastically as the local railworkers took the decision to go on strike, despite a circular to the contrary from the National Union of Railwaymen’s (NUR) headquarters in London. This raised the possibility of a national railway strike, which indeed, from reports sent to the NUR offices, seemed likely to spread across the channel. [31] The strike was delayed by intervention from an unlikely source. William O’Brien, general secretary and a key leader of the Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Council (ILPTUC) sent a telegram to the Limerick railworkers saying, ‘railwaymen should defer stoppage pending national action. National Executive specially summoned for tomorrow.’ [32] In Limerick this was taken to mean that the next day a general strike of Irish workers was to be called on their behalf. As the leader of the soviet, John Cronin, said in an interview, ‘the national executive council of the ILPTUC will change its headquarters from Dublin to Limerick. Then if military rule isn’t abrogated, a general strike of the entire country will be called.’ [33]

In fact, having sought advice during the course of three days of talks with leading nationalists, the leadership of the ILPTUC were anxious to defuse the crisis, not escalate it. [34] After considerable delay, they finally turned up in Limerick to reveal a plan that had been agreed with the nationalist activists, namely the evacuation of the population of Limerick. Understandably the Limerick workers were dismayed by this absurd proposition. As word of this scheme started to spread, the middle class, who had been cowed by the strength of the soviet, suddenly recovered their own political will and on Thursday 24 April Bishop Dr Hallinan and the Mayor entered into negotiations with General Griffin to obtain a compromise to the pass system. They then issued a letter the next day insisting on an immediate ending of the strike.

Stalemated by their own union leadership, the strike leaders gave up and effectively called the strike off when they said that all those who did not need to show passes should return to work immediately. Rank and file workers, threatening to set up another soviet, tore up the posters announcing this retreat. [35] But their position was an extremely difficult one. In Russia the soviets were based on direct elections from the workplace, so if a body of workers felt they were being misrepresented they could recall their delegate within twenty-four hours and give the mandate to another person. In Limerick the label ‘soviet’ was attached to the trades council because it was acting as a workers’ government. But the leaders of the movement were delegates elected through the slow moving workings of the individual trade union affiliates. To replace them in a matter of hours was impossible even if the majority of strikers desired to continue the fight.

The Limerick soviet, which had soared to unprecedented heights of working class activity, deflated with a whimper, with considerable damage to the position of the working class within the fight for Irish independence. As a local republican newssheet put it, the people had been let down ‘by the nincompoops who call themselves the ‘Leaders of Labour’.’ [36]

Outside of Limerick the curve of working class militancy was still on the rise. One mark of this was the strong response to the idea of holding a day’s strike on Thursday 1 May 1919 despite bans from the British and military authorities as well as local employers federations. Thousands participated in the action and the ILPTUC claimed that it was as effective as the general strike against conscription. In some ways it was all the more impressive in that this time there was no sanction from the church or nationalist leaders. In most small towns it was the ITGWU that was at the heart of the action, and their conference report that year boasted, ‘over more than three fourths of Ireland the cessation was complete and meetings were held at convenient centres at which the Labour propaganda was zealously pushed and the red flag of the workers’ cause displayed despite police interference.’ [37]

The high water mark of working class struggle in these years was undoubtedly the general strike for the release of hunger strikers that began on Monday 13 April 1920. Due to the increase in repression and republican activity over a hundred prisoners were being held in Mountjoy Jail, Dublin, without having been charged with any offence. On 5 April 1920, 36 socialists, trade unionists and nationalists took the decision to go on hunger strike. They were joined the next day by 30 more of their colleagues. Each day more prisoners joined in the protest action until by 10 April there were 91 hunger strikers. [38] Inside the prison they broke the furniture and in one wing demolished the walls between the cells. [39]

News of the jail protest spread quickly, crowds gathering outside the jail grew from hundreds to thousands. By the end of the first week of the hunger strike some 40,000 people were at the entrance to the jail, facing nervous-looking troops and armoured cars. As the attention of the country focused on this issue, the executive of the ILPTUC responded by calling for a national stoppage. They sent telegrams to the organisers of the ITGWU and placed a manifesto for the strike in the Evening Telegraph. [40]

The strike began with the railworkers of the Great Southern and Midland Company refusing to move a single train after 4.30pm on Monday 13 April 1920, except for the mail train which carried the instruction for a general strike. Then the Great Northern railworkers joined in. The next day most of the country was halted and governmental functions fell to local workers’ organisations, typically the Trades Council.

The Manchester Guardian reported the scene in Waterford, ‘the City was taken over by a Soviet Commissar and three associates. The Sinn Féin mayor abdicated and the Soviet issued orders to the population which all had to obey. For two days, until a telegram arrived reporting the release of hunger strikers, the city was in the hands of these men.’ [41] Freedom wrote that ‘never in history, I think, has there been such a complete general strike as is now for twenty-four hours taking place here in the Emerald Isle. Not a train or tram is running not a shop is open, not a public house nor a tobacconist; even the public lavatories are closed.’ [42] The summary of the Manchester Guardian was that, ‘in most places the police abdicated and the maintenance of order was taken over by the local Workers’ Councils ... In fact, it is no exaggeration to trace a flavour of proletarian dictatorship about some aspects of the strike.’ [43]

As with the Limerick soviet, workers undertaking such comprehensive action had to resolve the issues of control of food and transport. They did so by creating new structures to administer their areas. An example of how this occurred is given by an eyewitness who found himself in Kilmallock, East Limerick, during the strike, ‘a visit to the local Town Hall – commandeered for the purpose of issuing permits – and one was struck by the absolute recognition of the soviet system – in deed if not in name. At one table sat a school teacher dispensing bread permits, at another a trade union official controlling the flour supply – at a third a railwayman controlling coal, at a fourth a creamery clerk distributing butter tickets ... all working smoothly.’ [44]

The authorities were stunned by the action. The police and military were helpless to intervene in the face of such a widespread and effective movement. They concentrated on guarding the Mountjoy from being stormed: the crowds had suggested they might take such action by setting fire to a tank and testing entrances to the jail on Saturday 10 April, the night before the general strike was called. [45] That Sunday a serious confrontation loomed between the Dublin crowds, swelled by organised contingents of dockers and postal workers, and the British soldiers who were ordered to fix bayonets. Socialists distributed material appealing to the soldiers and appealed to them not to attack the demonstrators and it seemed as though a critical moment was approaching. [46] Would the crowds succeed in breaking in? Or would the soldiers open fire even at the cost of civilian lives and the potential political backlash that would accompany such an event?

The flashpoint was diffused up at the jail by Sinn Féin member of Dublin Corporation, John O’Mahony, who organised with a number of priests to form a cordon between the soldiers and the crowd and drove the demonstrators back from the jail entrance, shouting ‘in the name of the Irish Republic, go away’. He played the same pacifying role on the Tuesday by which time the authorities had realised the danger and brought up two more tanks, several armoured cars, barbed wire and considerable reinforcements. [47]

Although Britain was saved from experiencing a ‘Bastille Day’ by the intervention of Sinn Féin and the church, the authorities could not withstand the vast upsurge of soviet activity. They caved in and released all the hunger strikers, a situation described by the London Morning Post as one of ‘unparalleled ignominy and painful humiliation.’ [48] The lesson, that it was the working class that had the power to shatter the morale of the troops and police, while raising the confidence of the national movement, was not lost on the right-wing press. The Daily News drew the following conclusion from the general strike: ‘Labour has become, quite definitely, the striking arm of the nation ... It can justly claim that it alone possessed and was able to set in motion a machine powerful enough to save the lives of Irishmen when threatened by the British Government and that without this machine Dáil Éireann and all of Sinn Féin would have beaten their wings against the prison bars in vain.’ [49]

The other major intervention of the working class in the War of Independence was the boycott of the military by transport workers, especially the railworkers. On 20 May 1920, Michael Donnelly, a revolutionary socialist and friend of James Connolly’s, urged his fellow dockers to refuse to unload the 6,000-ton Polberg and the 1,000-ton vessel Anna Dorette Boog on the assumption the ships contained motor cars and other equipment for the military. [50] Soon porters and then railworkers were following suit and the action escalated to the boycott of all military cargos and troops.

The employers, especially the railway owners, reacted by suspending those workers who implemented the boycott. The labour leaders, notably William O’Brien, negotiated with Arthur Griffith and John Dillon that funds left over from the anticonscription campaign be used to provide payments for those who had been laid off. This was agreed and supplemented by a new appeal. Over the next six months an astonishing £120,000 was subscribed. [51]

Over the course of four months, the rail boycott undermined the British army’s ability to move troops quickly around the country. General Macready described the workers’ action as ‘a serious set-back for military activities during the best season of the year.’ Chief Secretary Sir Hamar Greenwood wrote that it put the Irish administration in a ‘humiliating and discredited position.’ [52] The railworkers nearly won a stunning victory when the Dublin administration conceded that railways would no longer be used to transport arms, ammunition and motor fuel. But the British Cabinet overruled this surrender. Instead, they attempted to ‘throttle’ the railway system and get Irish businesses to oppose a boycott that was leading to the cessation of rail services across the country. Eventually, the attrition of sackings told on the workforce. Only an all-out strike could have won in the latter stages of the boycott, but the price of assistance from the conservative nationalists was that the labour leaders quash such a demand. Although Ireland’s railworkers made a huge contribution to the ability of the IRA to operate with success, their own organisation disintegrated. The best-organised and most militant group of Irish workers were worn out by this boycott, which was ended on 21 December 1920.

With Britain being determined to resist at all costs Ireland becoming a republic, with the empire ready to expend a great deal of money and very many lives in preventing the emergence of anything more radical than a tightly constrained federal Irish parliament, the question arises, what events made them change their mind? Was it really the actions of the IRA backed up by a political leadership in Sinn Féin?

It is perhaps useful to take one microscopic case study. During the railworkers’ boycott of the British military, it happened on a number of occasions that a British officer, furious with the fact that a train full of soldiers was not moving from the station would go up to the engine, step on the plate, draw his revolver and point it at the head of the railway driver. On being told he must drive the train or he would be shot, the driver nevertheless refused to give way. It was the officer who climbed back down and ordered his men to disembark from the train, no doubt with a deep sense of frustration and humiliation.

When the officer stood with his finger on the trigger and the railworker stood looking at him, why didn’t the officer fire? And what gave the railworker the confidence that he wouldn’t fire? We can reject the explanation that ‘reasonableness’ and ‘non-violence’ in the British character came into play. Throughout 1920 there was pressure being exerted on the British forces in Ireland to intimidate the national movement and the pressure came from the top. The officer who stormed along the railway platform would have known full well that he was acting according to the desires of Lloyd George, General MacCready, and every member of the Cabinet, that the Irish population be made to feel the consequences of acts of insubordination. No one at the time felt it necessary to disguise the iron hand and most of the national British newspapers quite uncritically celebrated successful ‘reprisals’ by the Black and Tans. As Colonel Smyth notoriously told the RIC at Listowel, ‘no policeman will get into trouble for shooting any man.’ [53] Crown forces summarily executed several young Irishmen during this period and the Armritsar massacre of 1919 in India had provided further evidence that the British army was prepared to shoot civilians. So what restrained the officer from pulling the trigger in 1920?

Despite the burning of their property, the beatings and the deaths, the Irish population had not been cowed by the British forces and they had expressed this not only in their voting patterns but also in their mass popular activity. A near universal boycott as well as the resignations of many magistrates had caused the collapse of the legal system. Similar boycotts of the provision of food and other supplies to barracks had undermined the viability of locating Crown forces in smaller outposts. Even more effective was the participation of hundreds of thousands of people in strikes directed against the Empire. The general strike against conscription in 1918 and the strike for the release of socialist and nationalist prisoners in 1920 had rocked the British administration and given the participants a taste of victory. One of the best-organised trade unions in Ireland during the War of Independence was the National Union of Railwaymen, the solidarity between their members was unbreakable and their participation in the general strikes had provided a backbone to the actions. If the officer had shot the locomotive driver, Irish railway workers (and perhaps too their British counterparts, fellow NUR members) would have struck on behalf of their fallen comrade and no labour official could have stopped them.

The initial reaction of British Cabinet to the rising aspirations of the Irish population was to quell the movement through force, but repression is a crude tactic and if it fails to intimidate the subsequent radicalisation of the oppressed can be catastrophic for a ruling class. At some level the British officer must have sensed that the consequences of shooting the railworker were going to be disastrous for him personally and for those he served. His personal safety might have been at risk from the IRA, although this consideration alone might not have held his trigger finger, after all, only some 160 British soldiers were killed in Ireland between 1919 and 1921. Much more intimidating was the danger of a mass popular movement arising from the execution of the locomotive driver. Could the officer’s future be assured if his masters sought for ways to appease such a movement? And while the officer hesitated, the railworker faced him with a strength that was more than personal. It must have taken a lot of courage to look at the man holding the gun and refuse to obey him. And surely this courage was drawn from a faith in the fact that not only was he right to refuse, but also in a belief that there were hundreds of thousands of his fellow workers who backed him?

Despite considerable effort, by the middle of 1921 the British government had not managed to check the Irish national movement. Their position matched that of the officer in the sense that the choice they faced was to compromise or to unleash hell.

The latter course was a distinct option and that preferred by General Macready, but while plans were drawn up for the occupation of Ireland by 100,000 troops the majority of the Cabinet drew back from such a potentially hazardous confrontation. They changed their strategy for the same reason that the officer did not fire, because of the danger of a popular backlash, at the centre of which would have been the working class organisations who had already shown their capabilities through actions such as the Limerick soviet.

The key conclusion of this article then, is that the working class movement in the period 1916–1923 played an absolutely essential part in the national struggle. Without the willingness of hundreds of thousands of workers to boycott, strike, demonstrate and protest, the military activity of the three thousand or so IRA members who had managed to obtain guns would have proven insufficient to make the Cabinet choose the path of negotiation rather than repression. The Irish working class of this era were actors, not just witnesses, in the struggle.

1. See Conor Kostick, Revolution in Ireland (Cork 2009), pp. 118–124; Dan Bradley, Farm Labourers’ Irish Struggle 1900–1976 (Belfast 1988).

2. Irish Times, 24 April 1918.

3. William O’Brien papers, MS 15674 (1) ITGWU Branch returns.

4. Nicholas Smyth, Bureau of Military History, WS 721, p. 3. See also Fergal McCluskey, The Irish Revolution 1912–23: Tyrone (Dublin, 2014), pp. 75–6.

5. For example, Peter Hadden, Divide and Rule (Belfast 1980), p. 88.

6. Michael Farrell, The Great Belfast Strike of 1919, The Northern Star, no. 3 (1971) and Belfast Newsletter, 1 February 1919.

7. Belfast Newsletter, 31 January 1919.

8. Belfast Telegraph, 3 May 1919.

9. PRO, CAB 23/9, WC 523, 31 January 1919.

10. Belfast Newsletter, 29 January 1919.

11. Belfast Newsletter, 4 February 1919.

12. Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 22 February 1919.

13. Farrell, The Great Belfast Strike of 1919.

14. Irish Independent, 26 April 1919.

15. David Harkness, Northern Ireland since 1920 (Dublin 1983).

16. General Prisons Board, Jack Hedley and Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 5 July 1920.

17. Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 8 May 1919.

18. Austen Morgan, Labour and Partition (London 1991), p. 258.

19. Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 14 July 1920.

20. ILPTUC, Reports 1920 see also Morgan, Labour and Partition.

21. ILPTUC, Reports 1920.

22. The Irishman, 31 March, 1928.

23. The story of the Limerick Soviet is told excellently by Liam Cahill, Forgotten Revolution, Limerick Soviet 1919 (Dublin 1990).

24. Cahill, Forgotten Revolution, pp. 62–4.

25. Irish Independent, 15 April 1919.

26. Cahill, Forgotten Revolution, pp. 66–8.

27. Jim Kemmy, The Limerick Soviet, Saothar 6 (1980).

28. Cahill, Forgotten Revolution, p. 68.

29. Ibid., p. 74.

30. Ibid., p. 75.

31. Cahill, Forgotten Revolution, p. 113.

32. Irish Independent, 17 April 1919.

33. Ruth Russell, What’s the Matter with Ireland? (New York 1920), p. 93.

34. Cahill, Forgotten Revolution, pp. 106–8.

35. Ibid., pp. 115–7.

36. Ibid., p. 140.

37. ITGWU, Annual Report, 1919.

38. General Prison Board, Indexes, 1920 and Watchword of Labour, 17 April 1920.

39. Cork Examiner, 7 April 1920.

40. William O’Brien, Forth the Banners Go (Dublin 1969), p. 191.

41. In Emmet O’Connor, A Labour History of Waterford, Waterford Trades Council (Waterford 1989), p. 159.

42. In William O’Brien Papers.

43. Ibid.

44. Watchword of Labour, 15 May 1920.

45. Belfast Weekly Telegraph, 17 April 1920 and General Prison Board, Indexes, 1920.

46. Watchword of Labour, 24 April 1920 and Cork Examiner, 15 April 1920.

47. Cork Examiner, 12 and 14 April 1920.

48. London Morning Post, 4 June 1920.

49. Daily News, 15 April 1920.

50. Mike Milotte, Communism in Modern Ireland (Dublin 1984), p. 31.

51. Cahill, Forgotten Revolution, pp. 86–8.

52. Charles Townshend, The Irish railway strike of 1920: industrial action and civil resistance in the struggle for independence, Irish Historical Studies, XXI.83 (1979), pp. 265–82; Neville Macready, Annals of an Active Life (London 1924).

53. J.A. Gaughan (ed.), Memoirs of Constable J. Mee, RIC (Dublin, 1975), p. 104.

Conor Kostick Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 18 July 2021