Lissagaray: History of the Paris Commune of 1871

The Republic was threatened by the Assembly, it was said. Gentlemen, when the insurrection broke out, the Assembly was noted politically by only two acts: nominating the head of the executive power and accepting a republican cabinet. (Speech against amnesty by Larcy of the Centre Left, session of 18th May, 1876.)

To the rural plebiscite the Parisian National Guard had answered by their federation; to the threats of the monarchists, to the projects of decapitalization, by the demonstration of the Bastille; to D'Aurelles’ appointment, by the resolutions of the 3rd March. What the perils of the siege had not been able to effect the Assembly had brought about — the union of the middle class with the proletariat. The immense majority of Paris looked upon the growing army of the Republic without regret. On the 3rd the Minister of the Interior, Picard, having denounced ‘the anonymous Central Committee,’ and called upon ‘all good citizens to stifle these culpable demonstrations,’ no one stirred. Besides, the accusation was ridiculous. The Committee showed itself in the open day, sent its minutes to the papers, and had only held a demonstration to save Paris from a catastrophe. It answered the next day: ‘The Committee is not anonymous; it is the union of the representatives of free men aspiring to the solidarity of all the members of the National Guard. Its acts have always been signed. It repels with contempt the calumnies which accuse it of inciting to pillage and civil war.’ The signatures followed.[72]

The leaders of the coalition saw clearly which way events were drifting. The republican army each day increased its arsenal of muskets, and especially of cannon. There were now pieces of ordnance at ten different places — at the Barrière d'Italie, at the Faubourg St. Antoine, at the Buttes Montmartre. Red posters informed Paris of the formation of the Central Committee of the federation of the National Guards, and invited citizens to organize in each arrondissement committees of battalions and councils of legions, and to appoint the delegates to the Central Committee. The ensemble, the ardour of the movement seemed to bear witness to the powerful organization of the Central Committee. A few days more and the answer of the people would be complete if a blow were not struck at once.

What they misunderstood was the stout heart of the enemy. The victory of the 22nd January blinded them. They believed in the stories of their journals, in the cowardice of the National Guards, in the bragging of Ducrot, who, in the bureaux of the Assembly swore eternal hatred to the demagogues, but for whom, he said, he would have conquered.[73] The bullies of the reaction fancied they could swallow Paris at a mouthful.

The operation was conducted with clerical skill, method, and discipline. Legitimists and Orleanists, disagreeing. as to the name of the monarch, had accepted the compromise of Thiers, an equal share in the Government, which was called ‘the pact of Bordeaux.’ Besides, against Paris there could be no division.

From the commencement of March the provincial papers held forth at the same time, speaking of incendiarism and pillage in Paris. On the 4th there was but one rumour in the bureaux of the Assembly — that an insurrection had broken out; that the telegraphic communications were cut off; that General Vinoy had retreated to the left bank of the Seine. The Government, which propagated these rumours [74] despatched four deputies, who were also mayors, to Paris. They arrived on the 5th, and found Paris perfectly calm, even gay.[75] The mayors and adjuncts, assembled by the Minister of the Interior, attested to the tranquillity of the town. But Picard, no doubt in the conspiracy, said, ‘This tranquillity is only apparent. We must act.’ And the ultra-Conservative Vautrain added, ‘We must take the bull by the horns and arrest the Central Committee.'

The Right never ceased baiting the bull. Sneers, provocations, insults, were showered upon Paris and her representatives. Some among them, Rochefort, Tridon, Malon, and Ranc, when withdrawing after the vote mutilating the country, were followed by cries of ‘Pleasant journey to you.’ Victor Hugo defending Garibaldi was hooted. Delescluze demanding the impeachment of the members of the National Defence was no better listened to. Jules Simon declared that he would maintain the law against association. On the 10th the breach was opened. A resolution was passed that Paris should no longer be the capital, and that the Assembly should sit at Versailles.

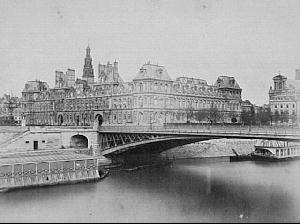

This was calling forth the Commune, for Paris could not remain at the same time without a Government and without a municipality. The field of battle once found, despair was to supply it with an army. The Government had already decided to continue the pay of the National Guards to those only who should ask for it. The Assembly decreed that the bills due on the 13th November, 1870, should be made payable on the 13th March, that is, in three days. The Minister Dufaure obstinately refused any concession on this point. Notwithstanding the urgent appeals of Millière, the Assembly refused to pass any protective bill for the tenants whose house-rents had been due for six months. Two or three hundred thousand workmen, shopkeepers, model makers, small manufacturers working in their own lodgings, who had spent their little stock of money and could not yet earn any more, all business being at a standstill, were thus thrown upon the tender mercies of the landlord, of hunger and bankruptcy. From the 13th to the 17th of March 150,000 bills were dishonoured. Finally, the Right obliged M. Thiers to declare from the tribune ‘that the Assembly could proceed to its deliberations at Versailles without fearing the paying stones of rioters,’ thus constraining him to act at once, for the deputies were to meet again at Versailles on the 20th.

D'Aurelles commenced operations against the National Guard, declaring he would submit it to rigorous discipline and purge it of its bad elements. ‘My first duty,’ said his order of the day, ‘is to secure the respect due to law and property'— this eternal provocation on the part of the bourgeoisie when lifted to supreme power by revolutionary events.

The other senators also joined in. On the 7th Vinoy threw into the streets with a pittance of eight shillings a head the twenty-one thousand mobiles of the Seine. On the 11th, the day on which Paris learnt of her decapitation and the ruinous decrees, Vinoy suppressed six Republican journals, four of which, Le Cri du Peuple, Le Mot d'Ordre, Le Père Duchêne, and Le Vengeur, had a circulation of 200,000. The same day the court-martial which judged the accused of the 31st October condemned several to death, among others Flourens and Blanqui. Thus everybody was hit — bourgeois, republicans, revolutionaries. This Assembly of Bordeaux, the deadly foe of Paris, a stranger to her in sentiment, mind, and language, seemed a Government of foreigners. The commercial quarters as well as the faubourgs rang with a general outcry against it. [76]

From this time the last hesitation disappeared. The mayor of Montmartre, Clémenceau, had been intriguing for several days to effect the surrender of the cannon, and he had even found officers disposed to capitulate; but the battalion protested, and on the 12th, when D'Aurelles sent his teams, the guards refused to deliver the pieces. Picard, making an attempt at firmness, sent for Courty, saying, ‘The members of the Central Committee are risking their heads,’ and obtained a quasi-promise. The Committee expelled Courty.

It had since the 6th met at the hall of the Corderie. Although keeping aloof from, and entirely independent of, the three other groups, the reputation of the place was useful to it. It gave evidence of good policy and baffled the intrigues of the commandant, Du Bisson, an officer who had served abroad and been employed in undertakings of an equivocal character, and who was trying to constitute a Central Committee from above with the battalion leaders. The Central Committee sent three delegates to this group, where they met with lively opposition. One chief of battalion, Barberet, showed himself particularly restive; but another, Faltot, carried away the Assembly, saying, ‘I am going over to the people.’ The fusion was concluded on the 10th, the day of the general meeting of the delegates. The Committee presented its weekly report. It recounted the events of the last days, the nomination of D'Aurelles, the menaces of Picard, remarking very justly, ‘That which we are, events have made us: the reiterated attacks of a press hostile to democracy have taught it, the menaces of the Government have confirmed it; we are the inexorable barrier raised against every attempt at the overthrow of the Republic.’ The delegates were invited to push forward the elections of the Central Committee. An appeal to the army was drawn up: ‘Soldiers, children of the people! Let us unite to serve the Republic. Kings and emperors have done us harm enough.’ The next day the soldiers lately arrived from the army of the Loire gathered in front of these red posters, which bore the names and addresses of all the members of the Committee.

The Revolution, bereft of its newspapers spoke now through posters, of the greatest variety of colour and opinion, plastered on all the walls. Flourens and Blanqui, condemned in contumacy, posted up their protestations. Sub-committees were being formed in all the popular arrondissements. That of the thirteenth arrondissement had for its leader a young iron founder, Duval, a man of cold and commanding energy. The sub-committee of the Rue des Rosiers surrounded their cannon by a ditch and had them guarded day and night.[77] All these committees quashed the orders of D'Aurelles and were the true commanders of the National Guard.

No doubt Paris was roused, ready to redeem her abdication during the siege. This Paris, lean and oppressed by want, adjourned peace and business, thinking only of the Republic. The provisional Central Committee, without troubling itself about Vinoy, who had demanded the arrest of all its members, presented itself on the 15th at the general assembly of the Vauxhall. Two hundred and fifteen battalions were represented, and acclaimed Garibaldi as commander-in-chief of the National Guard. An orator, Lullier, led the Assembly astray. He was an ex-naval officer, completely crack-brained, with a semblance of military instruction, and when not heated by alcohol having intervals of lucidity which might deceive any one. He was named commanding colonel of the artillery. Then came the names of those elected members of the Central Committee, about thirty in all, for several arrondissements had not yet voted. This was the regular Central Committee which was to be installed at the Hôtel-de-Ville. Many of those elected had formed part of the preceding commission. The others were all equally obscure, belonging to the proletariat and small middle class, known only to their battalions.

What mattered their obscurity? The Central Committee was not a Government at the head of a party. It had no Utopia to initiate. A very simple idea, fear of the monarchy, could alone have grouped together so many battalions. The National Guard constituted itself an assurance company against a coup-d'état; for if Thiers and his agents repeated the word ‘Republic,’ their own party and the Assembly cried Vive le Roi! The Central Committee was a sentinel, that was all.

What mattered their obscurity? The Central Committee was not a Government at the head of a party. It had no Utopia to initiate. A very simple idea, fear of the monarchy, could alone have grouped together so many battalions. The National Guard constituted itself an assurance company against a coup-d'état; for if Thiers and his agents repeated the word ‘Republic,’ their own party and the Assembly cried Vive le Roi! The Central Committee was a sentinel, that was all.

The storm was gathering; all was uncertain. The International convoked the Socialist deputies to ask them what to do. But no attack was planned, nor even suggested. The Central Committee formally declared that the first shot would not be fired by the people, and that they would only defend themselves in case of aggression.

The aggressor, M. Thiers, arrived on the 15th. For a long time he had foreseen that it would be necessary to engage in a terrible struggle with Paris; but he intended acting at his own good time, to retake the town when disposing of an army of forty thousand men, well picked, carefully kept aloof from the Parisians. This plan has been revealed by a general officer. At that moment Thiers had only the mere wreck of an army.

The 230,000 men disarmed by the capitulation, mostly mobiles or men having finished their term of service, had been sent home in hot haste, as they would only have swelled the Parisian army. Already some mobiles, marines, and soldiers had laid the basis of a republican association with the National Guards. There remained to Vinoy only the division allowed him by the Prussians and 3,000 sergeants-de-ville or gendarmes, in all 15,000 men, rather ill-conditioned. Lefô sent him a few thousand men picked up in the armies of the Loire and of the North, but they arrived slowly, almost without cadres, harassed, and disgusted at the service. At Vinoy’s very first review they were on the point of mutinying. They left them straggling through Paris, abandoned, mixing with the Parisians, who succoured them, the women bringing them soup and blankets to their huts, where they were freezing. In fact, on the 19th the Government had only about 25,000 men, without cohesion and discipline, two-thirds of them gained over to the faubourgs.

How disarm 100,000 men with this mob? For, to carry off the cannon, it was necessary to disarm the National Guard. The Parisians were no longer novices in warfare. ‘Having taken our cannon,’ they said, ‘they will make our muskets useless.’ The coalition would listen to nothing. Hardly arrived, they urged M. Thiers to act, to lance the abscess at once. The financiers — no doubt the same who had precipitated the war to give fresh impulse to their jobbery[78] — said to him, ‘You will never be able to carry out financial operations if you don’t make an end of these scoundrels.'[79] All these declared the taking of the cannon would be mere child’s play.

They were indeed hardly watched, but because the National Guard knew them to be in a safe place. It would suffice to pull up a few paving stones to prevent their removal down the narrow steep streets of Montmartre. On the first alarm all Paris would hasten to the rescue. This had been seen on the 16th. when gendarmes presented themselves to take from the Place des Vosges the cannon promised Vautrain. The National Guards arrived from all sides and unscrewed the pieces, and the shopkeepers of the Rue des Tournelles commenced unpaving the street.

An attack was nonsensical, and it was this that determined Paris remain on the defensive. But M. Thiers saw nothing, neither disaffection of the middle classes nor the deep irritation of faubourgs. The little man, a dupe all his life, even of a MacMahon prompted by the approach of the 20th March, spurred on by Jules Favre and Picard, who, since the failure of the 31st of October, believed the revolutionaries incapable of any serious action, and jealous to play the part of a Bonaparte, threw himself head foremost into the venture. On the 17th he held a council, and, without calculating his forces or those of the enemy, without forewarning the mayors — Picard had formally promised them not to attempt to use force without consulting them — without listening to the chiefs of the bourgeois battalions, [80] this Government, too weak to arrest even the twenty-five members of the Central Committee, gave the order to carry off two hundred and fifty cannon [81] guarded by all Paris.