The majority of the Bolshevik delegates remained in the Smolny until the early hours of October 26 and spent all that day in a feverish round of activity. The manifesto of the Second Congress of Soviets was transmitted all over the country and to all the armies by telegraph and telephone. The Military Revolutionary Committee was in almost continuous session. Its decisions were reached in consultation with Lenin, many of them being drafted by the leader of the revolution personally. Lenin urged that the normal life of the city which had been interrupted by the insurrection should be resumed as quickly as possible. In the morning, the Military Revolutionary Committee issued an order that all commercial establishments be opened on the 27th. It also took under its control all the vacant business premises and dwellings in the city.

Attention was concentrated mainly on securing the final defeat of the counter-revolution. The Military Revolutionary Committee ordered all trains carrying troops to Petrograd to be stopped. This order concluded with the following statement:

“In issuing the present order, the Military Revolutionary Committee trusts that the All-Russian Union of Railwaymen will give it its wholehearted support and calls upon all railway employees and workers who are loyal to the cause of the revolution to be vigilant.”[1]

A separate appeal was issued to all railwaymen informing them that the revolutionary government of Soviets was taking upon itself the duty of improving their material conditions.

Coming as it did after the recent conflict between the railwaymen and the Provisional Government, this appeal had tremendous effect. It drove a wedge between the rank-and-file railwaymen and the reactionary leaders of the Railwaymen’s Union and prevented the latter from turning the men against the revolution.

Lenin, Stalin and Sverdlov devoted a great deal of attention to the organization of the food supply and to the procuring of grain for Petrograd and the front.

In the evening, after a strenuous day, the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party met to discuss the composition of the new, Soviet Government. It was decided to call the new government the Council of People’s Commissars.

At the second and last session of the Congress of Soviets which opened at 9 p.m. on October 26, decisions of enormous historical importance were adopted. The first of these was to abolish capital punishment at the front, which had been restored by Kerensky, and immediately to release all revolutionary soldiers and officers who were under arrest. The next decision was to release the members of the Land Committees who had been arrested by order of the Kerensky government, and to transfer all local government to the local Soviets. This decision read as follows:

“Henceforth, all power is vested in the Soviets. The government Commissars are dismissed. The chairmen of the Soviets must communicate directly with the revolutionary government.”[2]

The Congress issued a special order to all the army organisations to take measures to secure the immediate arrest of Kerensky and to have him sent to Petrograd.

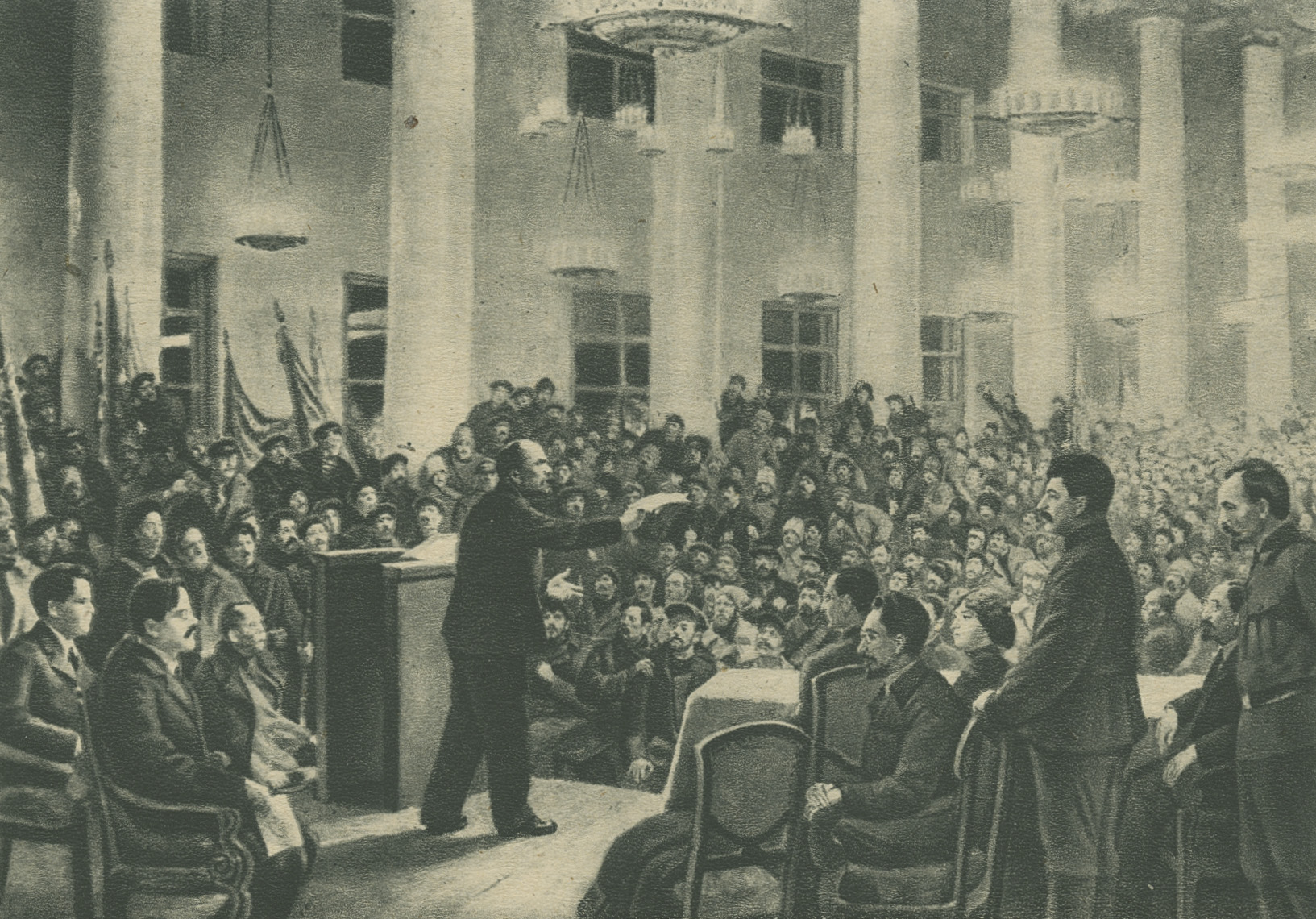

After passing these decisions the Congress proceeded to discuss its declarations on the fundamental issues, viz., peace and land. The reports on these two questions were made by Lenin. Up to this moment the Congress had not seen him; he had been in the Smolny, entirely absorbed in the work of organising the insurrection. Now he appeared on the platform of the Congress not only as the leader and teacher, as the masses had known him until then, but also as the organiser of the victory which the proletariat had achieved over the united forces of the counter-revolution.

The chairman had scarcely mentioned the name which had become world famous when an outburst of applause made the very rafters ring. The whole Congress rose to its feet. A storm of applause and enthusiastic cries of welcome greeted the leader of the greatest revolution the world had seen.

Hundreds of eyes were turned with admiration and love towards the platform where stood a man of short stature, with high, open forehead and keen, piercing eyes.

Lenin waited until the storm of greeting died down, but it was only after his repeated requests that the delegates at last became silent.

In his speech, which by its entire content seemed to emphasise that “there has been quite enough talk, it is time to get down to real work,” Lenin drew a borderline between two eras.

“The question of peace,” he said, “is a burning and urgent question of the day. Much has been said and written on the subject and all of you, no doubt, have discussed it at great length. Permit me, therefore, to proceed to read a declaration which the government you elect should publish.”[3]

This declaration—the Decree on Peace—was adopted by the Congress in the form of “An Appeal to the Peoples and Governments of the Belligerent Countries,” and began as follows:

“The Workers’ and Peasants’ Government created by the revolution of October 24-25 and backed by the Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies, calls upon all the belligerent nations and their governments to start immediate negotiations for a just, democratic peace.”[4]

It went on to explain that:

“By a just, democratic peace . . . the government means an immediate peace without annexations (i.e. without the seizure of foreign lands, or the forcible incorporation of foreign nations) and without indemnities.”[5]

It proposed that peace should be concluded forthwith, and expressed readiness to take the most resolute measures without the least delay,

“pending the final ratification of the terms of this peace by authoritative assemblies of the peoples’ representatives of all countries and all nations.”[6]

It went on to state that the Soviet Government did not

“regard the above-mentioned peace terms as an ultimatum; in other words, it is prepared to consider any other terms of peace, but only insists that they be advanced by any of the belligerent nations as speedily as possible, and that peace proposals should be formulated in the clearest terms without the least ambiguity or mystery.”[7]

At the same time, the Soviet Government proclaimed the abolition of secret diplomacy and expressed its firm determination to conduct all negotiations quite openly in sight of the whole people. It promised to proceed immediately to publish in full the secret treaties, which it forthwith proclaimed null and void.

It called for the immediate conclusion of a three months’ armistice and wound up with the following appeal to the proletariat of the three foremost capitalist countries in Europe—Great Britain, France and Germany.

“The workers of these countries will understand the duty that now rests with them of rescuing mankind from the horrors of war and its consequences . . . and will help us to achieve the success of the cause of peace, and at the same time of the cause of the emancipation of the toiling and exploited masses from all forms of slavery and all forms of exploitation.”[8]

The Decree on Peace adopted by the Second Congress of Soviets was of great international importance.

Russia’s economic development and the interests of her various nationalities demanded that she should withdraw from the unjust war. During the imperialist war Russia had steadily been reduced to the position of a semi-colony of foreign capital. Under the bourgeois Provisional Government this state of colonial dependence increased. By means of loans, the British and French imperialists were paving the way for the complete enslavement of the country. Russia was to compensate for the losses incurred by foreign imperialism, and German imperialism had designs of obtaining concessions in the West at Russia’s expense. But the Russian bourgeoisie was incapable of saving the country from this fate. Owing to its selfish class interests, and enmeshed as it was in a net of debt, the Russian bourgeoisie was to an increasing degree serving merely as the agent of foreign imperialism. Nor could the country be saved by the petty bourgeoisie, the upper strata of which whole-heartedly supported the big capitalists.

Moreover, almost the entire peasantry longed for peace, not for the sake of Socialism, and not exclusively for a “democratic” peace without annexations and indemnities, but peace primarily in order to be able to proceed to take over the landlords’ land.

The only class that could solve the problems of the national development of the country was the proletariat.

The Bolshevik Party had drawn up its peace platform long before it won power. As early as 1915, Lenin had said that upon winning power the Bolsheviks would offer a democratic peace to all the belligerent countries on terms that would ensure the liberation of the dependent and oppressed nations. If the governments of the day in Germany and the other belligerent countries rejected these terms, the Bolsheviks would carry out all the measures enumerated in the Party program. They would reorganise the country’s economy and prepare for and wage a revolutionary war in defence of Socialist society.

It was the working class led by the Bolsheviks which liberated the country from its state of semi-colonial dependence, extricated it from the unjust war, and paved the way for waging a just war.

The Russian proletariat began to express the national interests of the country. It became the embodiment of the hopes of the democratic sections of the population. But the proletariat solved the national-democratic problems of the country, not by means of a peaceful compromise with the government, but by the only means that were possible, revolutionary means, viz., by transforming the imperialist war into civil war. The Russian proletariat brought about a Socialist revolution and, in the process, it completed the unfinished work of the bourgeois-democratic revolution.

The Decree on Peace enunciated the principles of the foreign policy of the Soviet State. Distinctly and without ambiguity the decree proclaimed that the Soviet Government utterly renounced all aims of conquest. The decree delivered a shattering blow to the imperialist aims of the war and revealed its predatory nature to the world. In his speech on the peace question at the Congress of Soviets, Lenin said:

“No government will say exactly what it thinks. We, however, are opposed to secret diplomacy and will act openly, in full view of the whole people.”[9]

The peace program of the proletarian state was clear and definite from beginning to end. It was a state document addressed both to the governments and to the peoples of the belligerent nations. Lenin particularly emphasised this when he said:

“We cannot ignore the governments, for that would delay the possibility of concluding peace, and a people’s government dare not do that; but we have every right to appeal to the peoples at the same time. Everywhere there are differences between the governments and the people, and we must therefore help the peoples to intervene in the questions of war and peace.”[10]

Further, pointing out that the Soviet Government did not intend to submit its terms in the form of an ultimatum, Lenin said:

“We will, of course, insist upon our program of a peace without annexations and indemnities in its entirety. We shall not retreat from it; but we must not give our enemies the opportunity to say that their terms are different and that therefore it is useless to enter into negotiations with us. No, we shall not provide them with such an advantageous position and must not advance our terms in the form of an ultimatum.”[11]

In the ensuing debate Comrade Yeremeyev said in objection to this particular point: “They may take it as a sign of weakness and think that we are afraid.”[12]

Lenin made the following emphatic rejoinder to Yeremeyev’s objection:

“An ultimatum may prove fatal to our whole cause. We cannot allow some slight disagreement with our demands to serve the imperialist governments as a pretext for saying that it is impossible to enter into peace negotiations because we are too uncompromising.”[13]

But Lenin’s most effective reply to the argument that the terms should be presented in the form of an ultimatum was his statement that a peasant “from some remote province” would have every reason for saying:

“Comrades, why did you preclude the possibility of all sorts of peace terms being proposed? I would have discussed them, I would have examined them, and then would have instructed my representatives in the Constituent Assembly how to act.”[14]

Every word spoken by Lenin fell like refreshing rain upon sun-baked earth. The hundreds of delegates who filled the Smolny drank in every syllable. The plain and simple terms of Lenin’s speech and of the “Appeal” found an immediate response in the suffering hearts of millions of people of the various nations, for they expressed their most cherished hopes and aspirations.

The representatives of the oppressed nations unanimously supported the Bolshevik Decree on Peace.

The tall, well-built figure of Felix Dzerzhinsky appeared on the platform, his stern, ascetic face lit up with the joy of victory.

“We know,” he said, speaking on behalf of the working people of Poland, “that the only force that can liberate the world is the proletariat which is fighting for Socialism. . . .

“Those in whose name this declaration has been submitted are marching in the ranks of the proletariat and of the poor peasants, and all those who have left this hall at this tragic moment are not the friends but the enemies of the revolution and the proletariat. You will hear no response to this appeal from them; but it will find an echo in the hearts of the proletariat of all countries. With allies like that we shall achieve peace.

“We do not demand separation from revolutionary Russia. With her we shall always find common ground. We shall have a single fraternal family of nations, without strife and without discord.”[15]

Silence reigned in the hall. The delegates listened intently to the impassioned speech of this Polish revolutionary and became imbued with his confidence in victory. As Dzerzhinsky spoke it seemed as if the walls were being pushed outward and the hall expanding, giving the delegates a vision of the age-long fetters of tsarist Russia—the prison of nations—falling away.

One after another, fighters for the liberation of the oppressed nations came to the platform. On behalf of the Lettish proletariat and poor peasants the veteran revolutionary, Stuchka, supported the Decree on Peace. On behalf of the Lithuanian working people Comrade Kapsukas Mickiewicz said:

“There is no doubt that the Appeal will find an echo in the hearts not only of all the nations inhabiting Russia, but also of those in other countries. The voice of the revolutionary proletariat, the army and the peasantry will be borne over the bayonets into Germany and other countries and will help to achieve universal liberation.”[16]

At dawn on the day after the revolution the radio broadcast to the world the grand, wise words of the Soviet Decree on Peace, snapping the iron fetters of the imperialist war. People wept with joy on hearing them, and eyes, long dimmed by despair, shone again with reborn hope.

The Congress of Soviets adopted this historic decree with unrestrained enthusiasm. The proceedings were interrupted. The delegates jumped from their seats and mingled with the members of the Presidium. They flung their caps into the air, faces were flushed with excitement, and eyes glowed with joy.

The strains of the “Internationale”—the hymn of the proletarian struggle—merged with cries of greeting and thunderous cheers in honour of the great leader of the revolution.

One of the delegates mounted the platform and amidst cries of approval proposed that the Congress should greet Lenin as “the author of the Appeal and staunch champion and leader of the victorious workers’ and peasants’ revolution.”[17]

At this all the delegates rose to their feet and gave Lenin an ovation.

The cheering broke out anew when Lenin again rose to speak on the land question, the second item on the agenda.

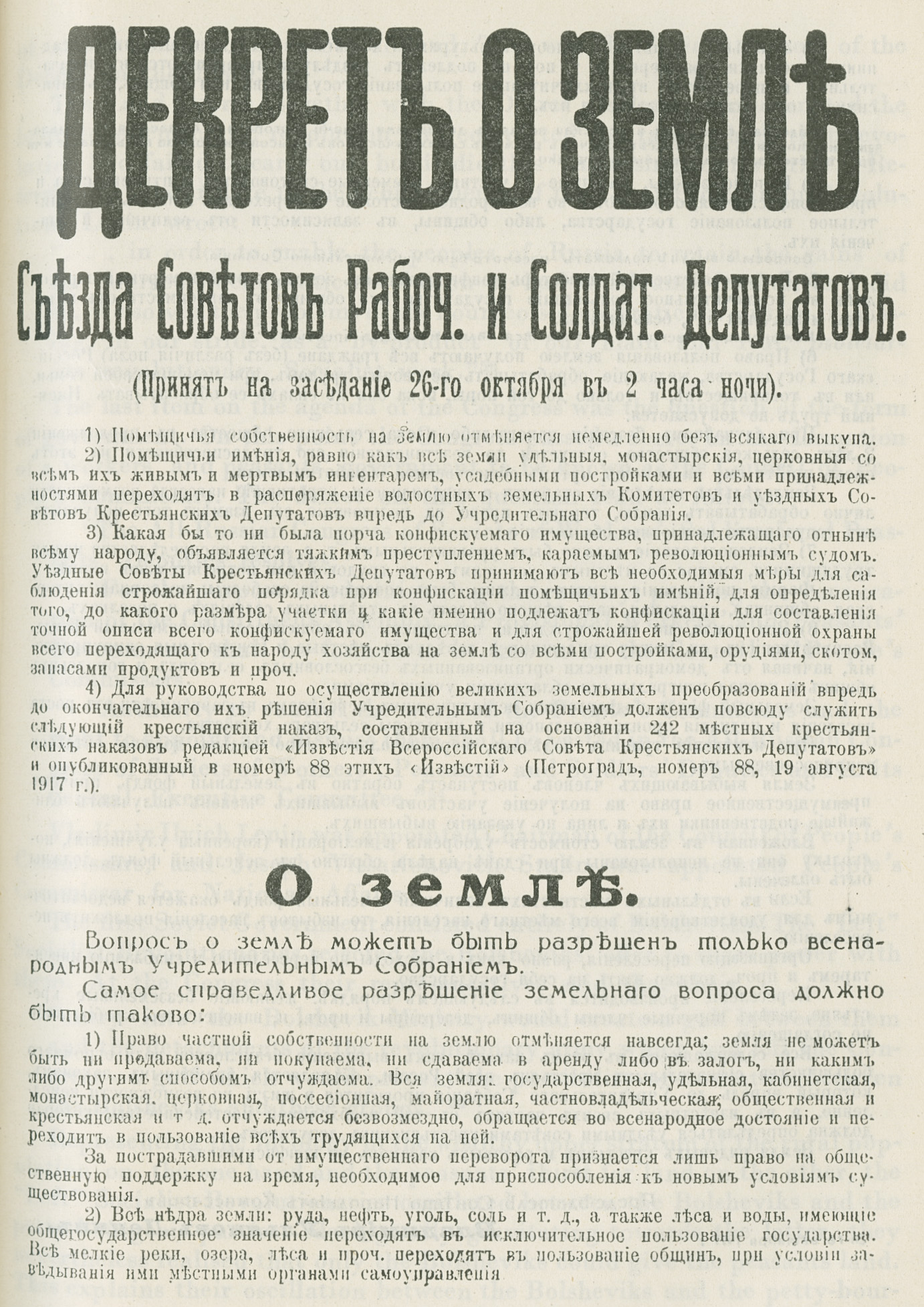

“I shall read you the points of a decree your Soviet Government must promulgate,” said Lenin, and in the silent hall the thrilling words of the “Decree on Land” were heard.

“1. Landlord property is abolished forthwith without compensation.

“2. The landed estates, as also all appanage, monasterial and church lands, with all their livestock, implements, farm buildings and everything pertaining thereto, shall be placed at the disposal of the Volost Land Committees and the Uyezd Soviets of Peasants’ Deputies pending the convocation of the Constituent Assembly.”[18]

The decree went on to state that “all damage to confiscated property, which henceforth belongs to the whole people, is proclaimed a felony punishable by the revolutionary courts.”[19]

The Uyezd Soviets were enjoined to take all necessary measures to guarantee the observance of strict order during the confiscation of the landed estates and to protect in a revolutionary way all agricultural enterprises that were transferred to the people.

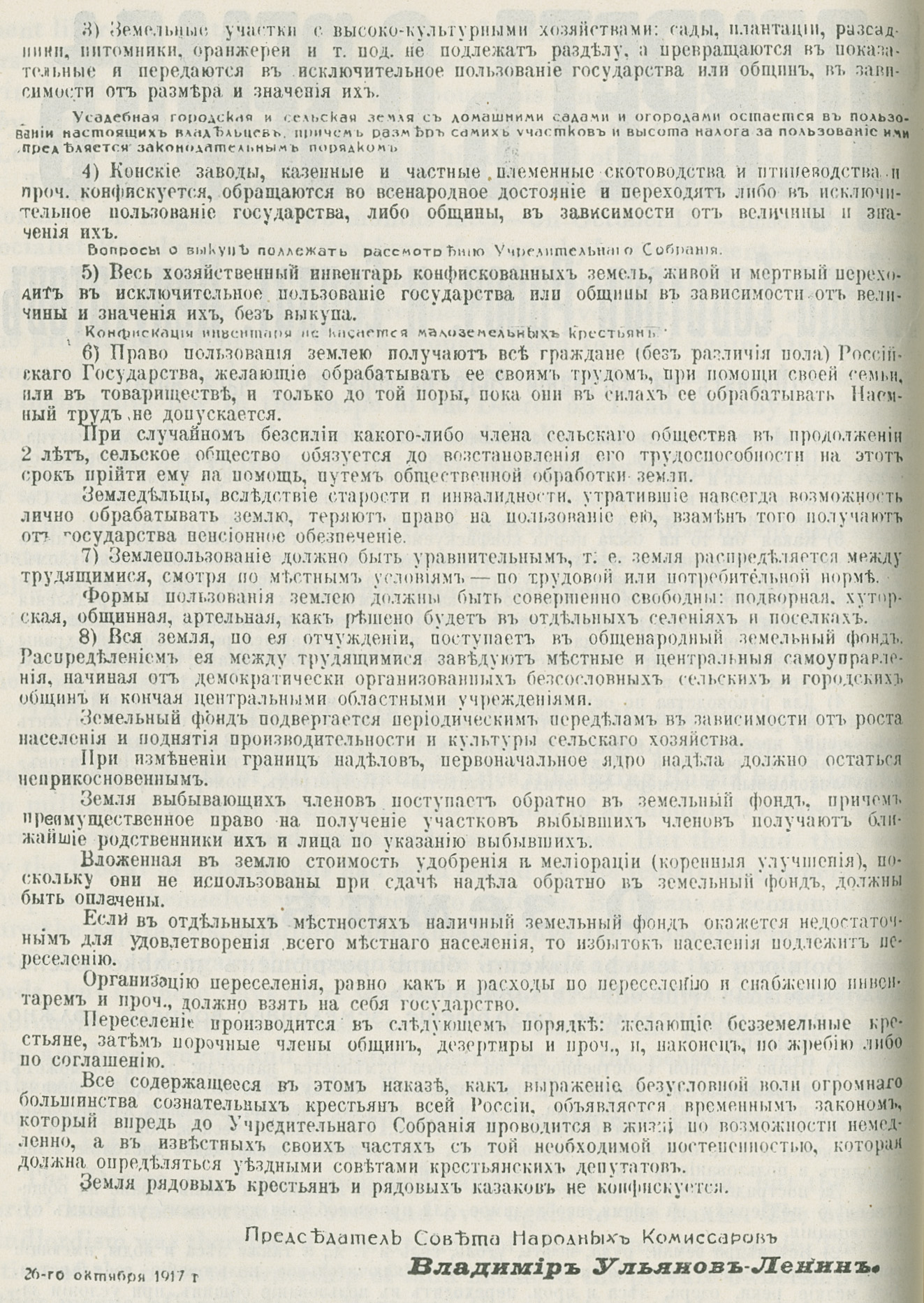

Everywhere, the work of carrying through the great land reform was to be guided by the 242 local Peasant Instructions which had been published in Izvestia of the All-Russian Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies “pending a final decision by the Constituent Assembly.”[20]

The last point of the decree contained the proviso that “the land of ordinary peasants and ordinary Cossacks shall not be confiscated.”[21]

The decrees on the land and peace, occupied the foremost place in the series of important decisions adopted by the Soviet Government.

The vast majority of the peasants had long been waiting for the expropriation of the landlords. This measure, which the bourgeois-democratic revolution proved incapable of carrying out, was secured by the decree on the land. In his speech Lenin explained the main purpose of this decree as follows:

“The object is definitely to assure the peasants that there are no longer any landlords in the countryside, that they themselves must decide all questions, and that they themselves must arrange their own lives.”[22]

The Decree on Land proved to the peasants that the Soviet Government was finally and irrevocably abolishing landlordism and its oppression and exploitation in the rural districts. At the same time it was a guarantee that the land would really be placed at the peasants’ disposal.

In connection with point 4 of the decree on the land, which stated that the work of carrying through the great land reforms should be guided by what were known as the “Peasant Instructions,” the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks levelled a series of charges against the Bolsheviks. The facts of the case are that on the basis of the 242 Instructions, which had been given to the peasant delegates to the First All-Russian Congress of Peasants’ Deputies, the Socialist-Revolutionaries had drawn up “Model Instructions,” which summed up all the peasants’ demands. These Model Instructions were published in Izvestia of the All-Russian Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies on August 19, 1917. They proclaimed all the land the property of the people, to be “transferred to those who tilled it.”[23] They advocated “equal land tenure” and prohibited the employment of hired labour in agriculture. This Socialist-Revolutionary land program ran counter to the Bolshevik program for the nationalisation of the land. The Bolsheviks were also opposed to equal land tenure, to the prohibition of hired labour, and to other points in the “Instructions.”

But on one point—and that the decisive one—the “Instructions” had this in common with point 17 of the Bolshevik program—which had been formulated at the April Conference—that both demanded the confiscation of all landlord, appanage and monasterial land, and its transfer to the local Soviet bodies, viz., the Soviet and Volost Committees. This was the fundamental and most important revolutionary measure for which the peasants were waiting. The important thing was to confiscate the land from the landlords and declare that the peasants had the right to cultivate it; to proclaim the abolition of landlord tyranny. Insofar as the majority of the peasants had in an organised manner expressed the wish to arrange the use of the confiscated land in the way indicated in the “Instructions,” the first document on the land issued after the October Socialist Revolution had to ratify this right.

It must be observed that this situation did not come as a surprise to Lenin and the Bolshevik Party. Long before the October Revolution, on the eve of the Fourth Congress of the Bolshevik Party, Lenin wrote a pamphlet entitled A Revision of the Agrarian Program in which he stated:

“To remove all idea that the workers’ party wants to thrust any project of reform upon the peasants against their will and without regard for the independent peasant movement, we have appended to the draft program variant A, which, instead of the direct demand for nationalisation, contains the statement that the Party will support the revolutionary peasants in their desire to abolish the private ownership of land.”[24]

It is well known that Lenin had always advocated this position when the agrarian program had been discussed. He had emphasised that this program “would under no circumstances cause strife between the peasantry and the proletariat as the fighters for democracy.”[25]

Lenin, therefore, had every ground for stating at the Second Congress of Soviets that the accusation that the Bolsheviks had borrowed another party’s program was frivolous. On this point Lenin said:

“Voices are being raised here to the effect that the decree itself and the ‘Instructions’ were drawn up by the Socialist-Revolutionaries. What of it? Does it matter who drew them up? As a democratic government, we cannot ignore the decision of the rank and file of the people, even though we may disagree with it. From the experience of applying the decree in practice, and carrying it out locally, the peasants will themselves realise where the truth lies. And even if the peasants continue to follow the Socialist-Revolutionaries, even if they give this party a majority in the Constituent Assembly, we shall still say—what of it? Experience is the best teacher, and it will show who is right. Let the peasants solve this problem from one end while we solve it from the other.”[26]

The very fact that the Bolsheviks—while not concealing their disagreement with certain points of the “Instructions”—accepted the latter as the basis of the agrarian platform of the October Revolution testifies to the wisdom, foresight and realism of Lenin’s policy on this question. The Party foresaw that in putting the law into operation the peasants would adopt the Bolshevik solution of the problem “from the other end,” that they themselves would drop the petty-bourgeois, Socialist-Revolutionary “equal tenure” slogans and proceed to organise agriculture on new lines. They knew that experience would teach the peasants that equal land tenure would not liberate the poorer peasants from bondage to the kulaks. The abolition of the yoke of landlordism would be immediately followed by a struggle between the poor classes of the rural districts and the kulaks over the question of distributing the land, of cultivating it, the distribution of farm implements, and so forth.

The program outlined in the “Instructions” had virtually ceased to be the program of the Socialist-Revolutionaries, for the latter had staunchly supported the Provisional Government in its efforts to prevent the peasants from confiscating the land from the landlords, i.e., from carrying out their own, i.e., the Socialist-Revolutionaries’ “Instructions.” In these circumstances, the Decree on Land was a special method of isolating the Socialist-Revolutionaries from the peasants. At one stroke the Soviet Government liberated vast masses from the influence of the compromisers. The first act of the Soviet Government—which was confronted with the task of winning the masses away from the bourgeois and petty-bourgeois parties “by satisfying their most urgent economic needs in a revolutionary way” (Lenin)[27]—was to satisfy precisely this demand of the peasants.

The “Peasants’ Instructions” were published by the Socialist-Revolutionaries on August 19. Two months later—on October 18—these very same Socialist-Revolutionaries—members of Kerensky’s government—published a Ministerial Land Bill which directly ran counter to the “Instructions.” The “Peasants’ Instructions” were shelved for over two months, and it was the proletarian revolution which brought them to light again. On Lenin’s proposal, the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets transformed them into an immutable law in the shape of the Decree on Land, thereby proving to the peasants that the Party of Lenin and Stalin did more for the working people in one day than the Socialist-Revolutionaries had done in the course of seven months of the revolution.

The Decree on Land was ratified with only one dissentient and eight abstentions. The feeling of the Congress was vividly expressed by a peasant delegate from the Tver Gubernia who stated that he had brought from his constituents “profound respects and greetings to the present assembly” and also “greetings and thanks to Comrade Lenin as the staunchest champion of the poor peasants.”[28]

This speech was greeted with an outburst of thunderous applause.

The peasants had been fighting for land for hundreds of years. Many generations of peasants of all the nationalities inhabiting Russia had ploughed up millions of acres of virgin soil, had by dint of arduous toil cleared dense forests and had reclaimed wastelands and marshes. But the land thus won by the labour of generations had been seized by the feudal landowners, and the peasants themselves were reduced to serfdom. By means of economic pressure the capitalists, landlords and kulaks drove the peasants “into the desert.” Time and again the peasants rose in revolt against the predatory landlords, but in those days there was no proletariat—the only consistently and thoroughly revolutionary class—to take the lead of the peasant movement. The age-long, vague and impotent yearnings of the peasants were realised only after the October Socialist Revolution. The land was confiscated, taken from the landlords without compensation, by the now victorious oppressed classes led by the proletariat.

The Decree on Land abolished landlordism in Russia, but the landlords’ land was mortgaged over and over again to the banks. The blow at landlordism was therefore a blow at the capitalist system as a whole. The abolition of the private ownership of land menaced the private ownership of all other means of production. Moreover, the abolition of the private ownership of land broke down the peasants’ age-long proprietary prejudices. The way was cleared for new, Socialist forms of agriculture to replace the old, feudal forms, which had kept the bulk of the peasantry in a state of starvation on tiny plots of land. This was the Socialist aspect of the Decree on the Land.

The Land Decree, together with the Decree on Peace, consummated the bourgeois-democratic revolution and completed the tasks which that revolution had failed to carry out; but it did this “in passing, in its stride.” Referring at a later date to the achievements of the Great Proletarian Revolution, Lenin wrote:

“. . . in order to enable the peoples of Russia to retain the gains of the bourgeois-democratic revolution we had to advance further, and did so. We solved the problems of the bourgeois-democratic revolution in passing, in our stride, as a ‘by-product’ of our main and real, proletarian revolutionary, Socialist work.”[29]

The last item on the agenda of the Congress was the question of the form of government. On this point the Congress passed a decree on the formation of a workers’ and peasants’ government to be known as the Council of People’s Commissars. The decree on this question read as follows:

“The All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies resolves:

“For the purpose of administering the country, pending the convocation of the Constituent Assembly, a Provisional Workers’ and Peasants’ Government, shall be formed to be known as the Council of People’s Commissars.

“Authority to control the work of the People’s Commissars and the right to appoint and dismiss them shall be vested in the All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’, Peasants’ and Soldiers’ Deputies and in its Central Executive Committee.”[30]

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was appointed Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, and Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was appointed People’s Commissar for National Affairs.

The first Soviet Government consisted entirely of Bolsheviks. The “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries rejected the Bolsheviks’ offer to share power with them. At the Congress their representatives said that their

“entry into the Bolshevik Ministry would create a gulf between them and the detachments of the revolutionary army which had left the Congress—a gulf which would prevent the possibility of mediation between the Bolsheviks and these groups.”[31]

Representing the ideology of the wealthy upper stratum of the rural population on the one hand and the peasants’ thirst for land on the other, the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries oscillated between the Bolsheviks and the petty-bourgeois parties. Ideologically gravitating towards the latter, they nevertheless realised that only the Bolsheviks could give the peasants land. This explains their oscillation between the Bolsheviks and the petty-bourgeois parties. They were temporary fellow-travellers of the proletarian revolution, likely to desert and betray it at a critical moment.

In conclusion, the Congress elected a Central Executive Committee of 101 members, of whom 62 were Bolsheviks, 29 “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries, six United Internationalist Social-Democrats, three Ukrainian Socialists, and one Maximalist Socialist-Revolutionary.

At 5:15 a.m. on October 27, the Second Congress of Soviets drew to a close amidst loud cries of “Long live the Revolution!” “Long live Socialism!”[32] and the strains of the “Internationale.”

Thus came into being the Soviet Government—the first Workers’ and Peasants’ Government in history.

Day was already breaking when the delegates left the Smolny. Taking with them bundles of newspapers and leaflets fresh from the press, and loaded with Bolshevik literature, they hastened to the railway stations, eager to return to their respective districts in order to carry the news of the victory of the proletarian revolution to all parts of the country.

[1] “The Orders of the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies,” Izvestia of the Central Executive Committee and of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, No. 208, October 27, 1917.

[2] Central Archives, The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, State Publishers, Moscow-Leningrad, 1928, p. 57.

[3] V. I. Lenin, “The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, November 7-8 (October 25-26), 1917. Report on Peace, November 8 (October 26),” Lenin and Stalin, 1917, Eng. ed., p. 618.

[4] Ibid., pp. 618-19.

[5] Ibid., p. 619.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid., p. 620.

[8] Ibid., p. 621.

[9] Ibid., p. 622.

[10] Ibid., p. 621.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Central Archives, The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, State Publishers, Moscow-Leningrad, 1928, p. 65.

[13] V. I. Lenin, “The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, November 7-8 (October 25-26), 1917, Report on Peace, November 8 (October 26),” Lenin and Stalin, 1917, Eng. ed., p. 623.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Central Archives, The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, State Publishers, Moscow-Leningrad, 1928, pp. 17-18.

[16] Ibid., p. 18.

[17] Ibid., p. 21.

[18] V. I. Lenin, “The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, November 7-8 (October 25-26), 1917, Report on the Land, November 8 (October 26),” Lenin and Stalin, 1917, Eng. ed., p. 626.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid., p. 627.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid., p. 630.

[23] Ibid., p. 627.

[24] V. I. Lenin, “Revision of the Agrarian Program,” Collected Works, Russ. ed., Vol. IX, p. 74.

[25] Ibid.

[26] V. I. Lenin, “The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, November 7-8 (October 25-26), 1917, Report on the Land, November 8 (October 26),” Lenin and Stalin, 1917, Eng. ed., p. 629.

[27] V. I. Lenin, “The Elections to the Constituent Assembly and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat,” Collected Works, Russ. ed., Vol. XXIV, p. 640.

[28] Central Archives, The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, State Publishers, Moscow-Leningrad, 1928, p. 74.

[29] V. I. Lenin, “The Fourth Anniversary of the October Revolution,” Collected Works, Russ. ed., Vol. XXVII, p. 26.

[30] Central Archives, The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, State Publishers, Moscow-Leningrad, 1928, pp. 79-80.

[31] Ibid., p. 83.

[32] Ibid., p. 92.

Previous: The Opening of the Congress

Next: The Counter-revolutionary Insurrection Against the Soviet Government