Neocolonialism by Kwame Nkrumah 1965

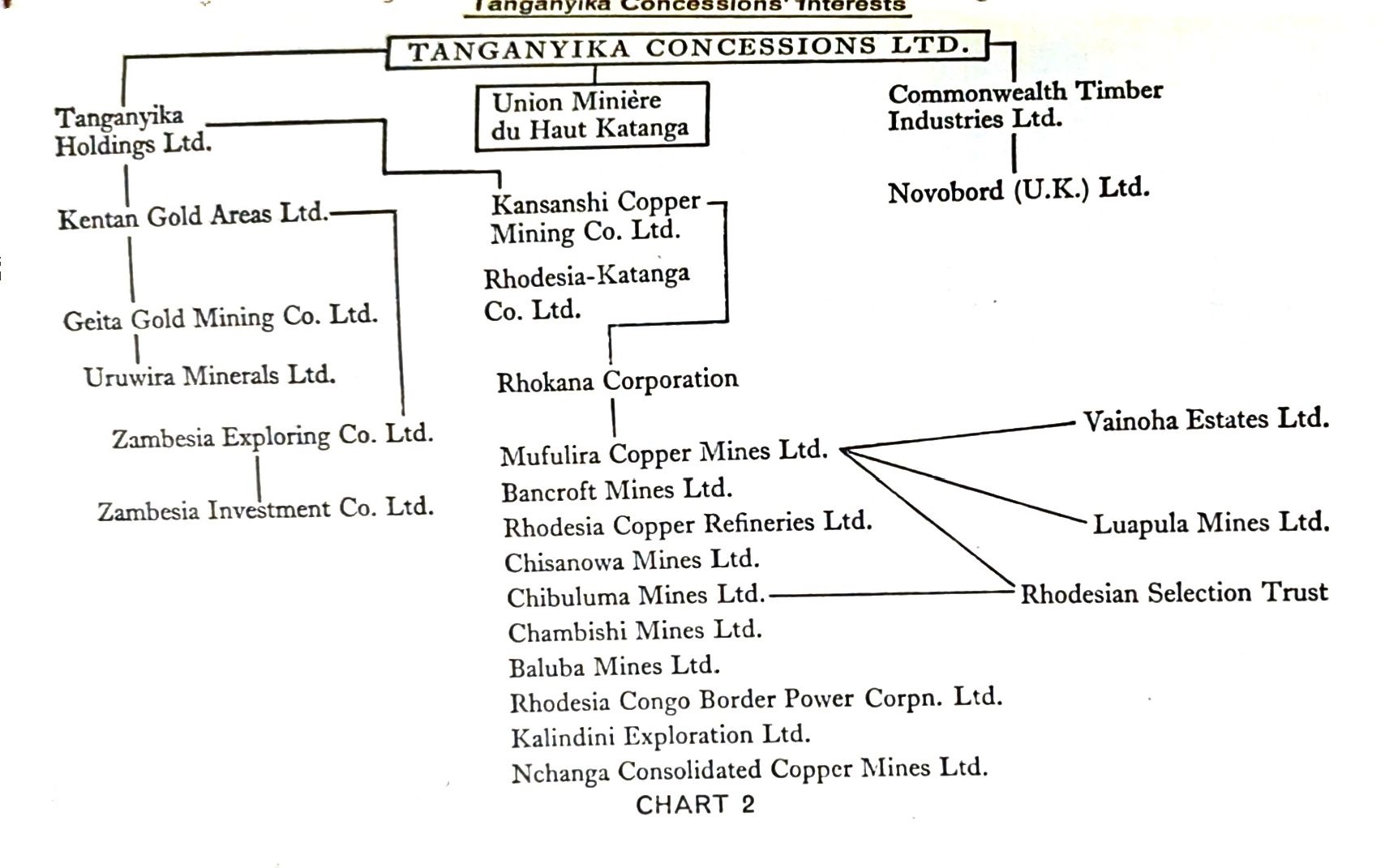

TO give anything like a complete account of the complicated network of foreign companies which at present governs so much of Africa’s economic life, would be impossible within the space of a single book. Yet some reference to the most important of them is necessary, and in many cases their connecting interests can be shown in diagram form. Behind the facade of separateness strong connecting links bind these powerful firms together.

In East Africa, one of the most powerful concerns is Tanganyika Concessions. The name is misleading. It was actually registered in London towards the end of January 1899. Today control of the company is wielded from Salisbury, Rhodesia, whence it was removed in the latter part of 1950. Operations in Tanganyika have not yet been fully developed, though they cover two important gold mines and a mineral company, and include some prospecting. The company’s writ has greater significance in Zambia, where it acquired from British South Africa Co. a concession over a large area, together with certain prospecting rights. From Zambia its activities spawn into the Congo, where it controls a mineral concession of 60,000 square miles secured from the Katanga (Belgian) Special Committee. For giving Tanganyika Concession rights over this expanse of Congolese land, the Katanga Committee enjoyed the benefit of a 60 per cent share in the royalty paid by Union Minière.

We must not for one moment, however, allow ourselves to be led into the error of thinking that Tanganyika Concessions thus permitted themselves to be ‘bested’ by the Special Committee. The company became a member of the Committee. In the way of financiers who, cautiously and shrewdly, do not place all their eggs in a single basket, a new organisation was created to take care of a concession covering a surface about three-fifths the sizeof Ghana. This is the celebrated Union Minière du Haut Katanga, whose reputation over the years has become notorious for the merciless exploitation of the Congo.

Another strategic interest of Tanganyika Concessions is the railway running from Lobito Bay in Angola up to the Angola-Congo border, operated by the Benguela Railway Company (Companhia do Cominho de Ferro de Benguela). The railway company is a creation of Tanganyika Concessions which holds £2,700,000 or 90 per cent of its £2 shares, as well as the whole of the debenture capital. The Benguela Railway, during 1961, built a branch line from the town of Robert Williams into the mining region of Guima, which was opened in August 1962. Commonwealth Timber Industries Ltd., a vast forestry and lumber concern, is also 60 per cent owned by Tanganyika Concessions.

Novobord (U.K.) Ltd., the English affiliate of Commonwealth Timber, was able, with the assistance of the African companies with which Société Générale is associated, to construct a sawmill and factory for the manufacture of fibrewood panels at Thetford in Norfolk. The factory’s capacity will make possible the production of about 25 million square feet of panels yearly, the capital invested being around £2 million.

When Tanganyika Concessions was about to change its headquarters from London to Salisbury, it gave an undertaking to H.M. Treasury which no doubt had some bearing on the British government’s vacillating policy in the breakdown of the Central African Federation. It must also colour its behaviour in regard to the Congo and to Portuguese rule in Africa. The undertaking provided that for a minimum period of ten years, Tanganyika Concessions would not, without consent of the British Treasury, ‘dispose of or charge or pledge its interests or any part thereof in Union Minière du Haut Katanga or the Benguela Railway’ except, in the case of the latter, to the Portuguese Government under the terms of the Concessions Agreement.

The limitation did not end with the expiration of the ten-year period, as a conjunctive clause provided that subsequently ‘no sale or disposal of such interests or any part thereof (except as aforesaid) shall be made without the securities proposed to be sold or otherwise disposed of first being offered to H.M. Treasury at the same price and on the same terms as have been offered to a third party’.

These provisions have given the British Government a direct concern in the operations of Tanganyika Concessions, Union Minière and the Benguela Railway which is bound to influence their behaviour in relation to the independence struggle in Southern and Central Africa. More particularly, in view of the special relations which Great Britain has had with its oldest ally, Portugal. From the point of view of the companies themselves, they must feel encouraged by this special interest of the British Government in maintaining their strategic position across the great central belt of Africa.

Tanganyika Concessions, both directly and through Tanganyika Holdings, has an important participation in Rhodesia-Katanga Co. Ltd., with which, in conjunction with Zambesia Exploring, interests were acquired in the Kakamega Goldfield, Kenya, which were transferred to Kentan Gold Areas, in which Rhodesia-Katanga has a substantial holding. Rhodesia-Katanga is indebted to the British South Africa Co. by reason of the perpetual mining rights the latter has granted it over any minerals, including coal but excluding diamonds and precious stones, which may be found in about 2,5000 square miles of Zambia. Additionally, it has perpetual coal mining rights in twenty areas of 300 acres, each subject to 15 per cent interest of the British South Africa Co.

To complete Tanganyika Concessions’ roster of subsidiaries, there is the wholly owned Tanganyika Properties (Rhodesia) Ltd., registered in Salisbury, Rhodesia. It provides office and staff accommodation together with allied services, as well as holding certain investments.

Consolidated profit made by Tanganyika Concessions for the year ended 31 July 1961 was £3,296,325 out of a total revenue of £4,462,667. Its current assets are £4,380,163 in shares and debentures of Benguela Railway Co.: £5,300,318 in shares and loan to Commonwealth Timber Industries; £1,317,793 in Tanganyika Holdings; and £4,019,629 in Union Minière, whose ramifications will be examined in a later chapter.

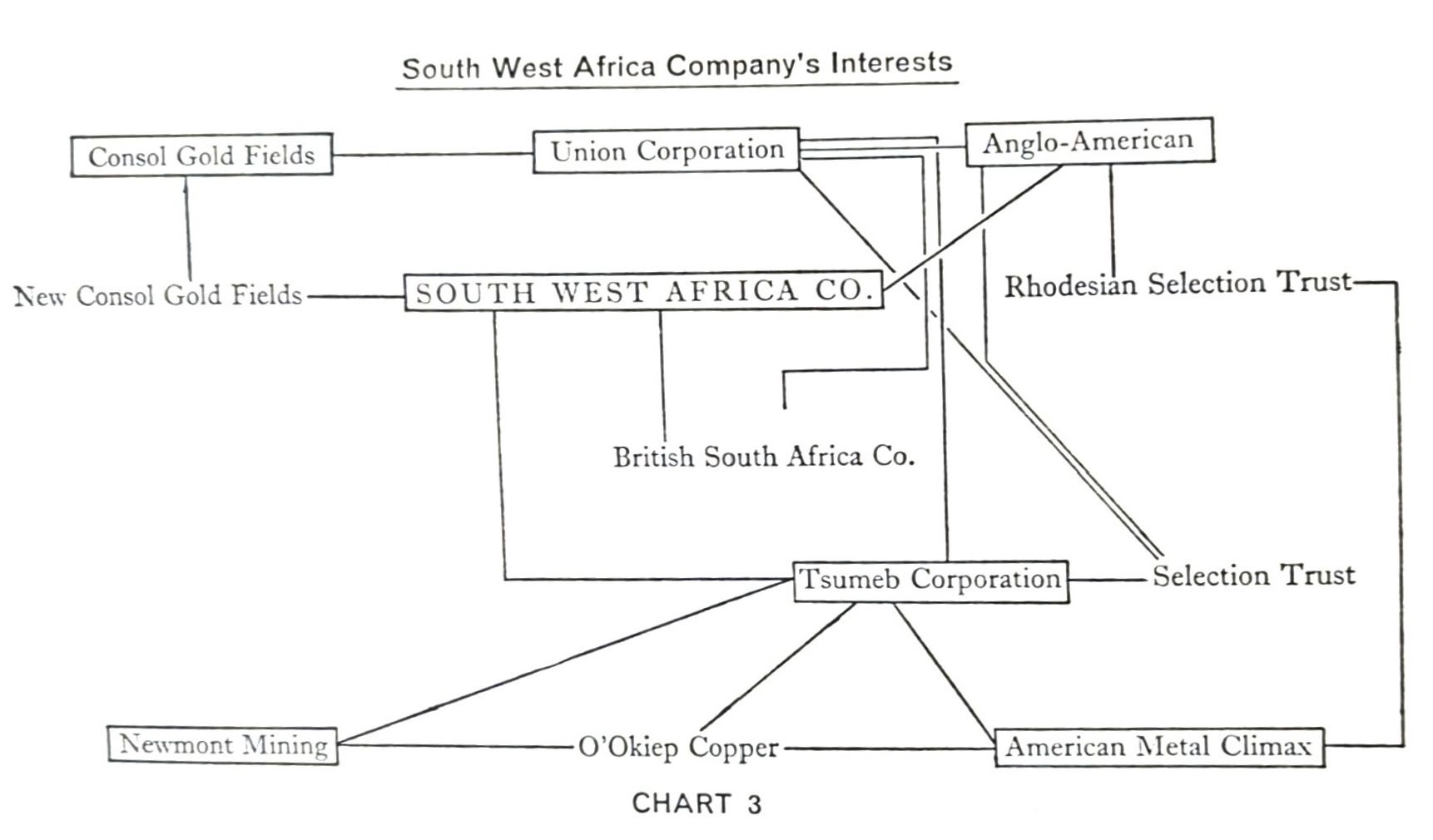

Coming to the South-West Africa Co. Ltd. we find Anglo American Corporation and Consolidated Gold Fields merging to exploit a vast section of wealth of southern Africa.

The South-West Africa Co. Ltd. was registered in London on 18 August 1892, and has a special grant of exclusive prospecting and mining rights over some 3,000 square miles of the Damaraland concession area of South-west Africa. This grant was made by the Administration of South-west Africa for a period of five years from 2 January 1942, and has since been renewed until 2 January 1967. The company also holds mining areas in various other districts of South-west Afrcia. It produces tin-wolfram and zinc-lead concentrates as well as vanadates.

Large areas of land such as those held by the South-West Africa Co. demand extremely heavy capital investment to exploit and encourage the formation of alliances between groups desirous of controlling output, distribution, and hence the prices of raw materials. Not only that, it facilitates the channelling of their processing through the allied organisations. To pursue this policy of co-ordination, the South-West Africa Co. signed an agreement with a joint Anglo American-Consolidated Gold Fields venture by which it sub-leased certain of its rights to explore and exploit its concessions. See Chart 3.

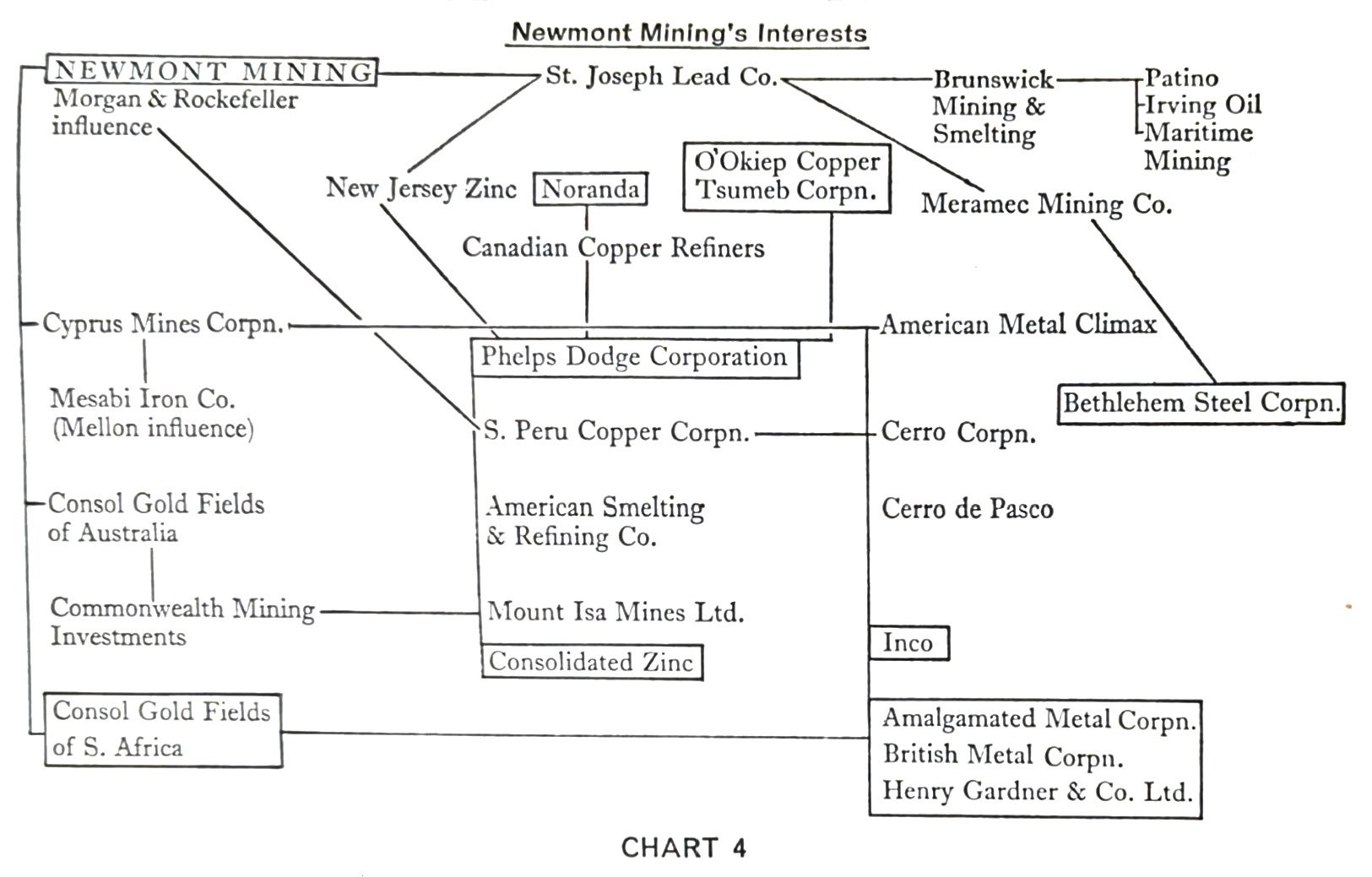

The Newmont Mining Corporation was formed in Delaware, U.S.A., on 2 May 1921. The purpose of the company is to acquire, develop, finance and operate mining properties. For this purpose a share capital of $60 million has been authorised. At 31 December 1961, 2,824,518 of the authorised six million ten-dollar shares had been issued, and paid up. Mining exploration is carried on by the company through Newmont Exploration Ltd. (Delaware), Newmont Mining Corporation of Canada Ltd. and Newmont of South Africa (Pty) Ltd. Chart 4 gives some idea of the extent of their interests.

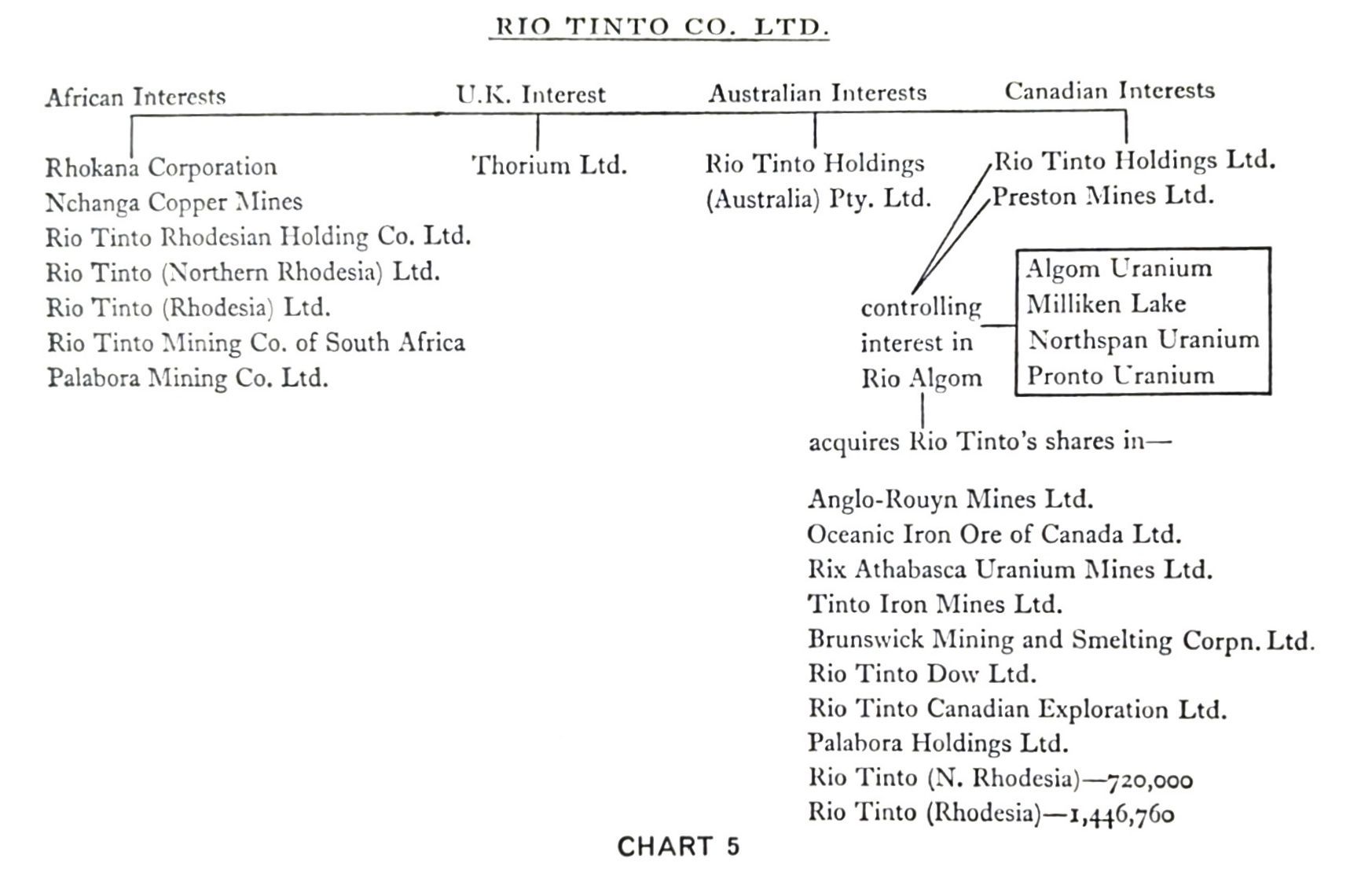

We have already met certain of the Rio Tinto companies in Zambia and Rhodesia, and have touched upon others in connection with the Société Générale de Belgique’s associations with the North American financial and industrial scene. The Rio Tinto complex is one that would be hard to miss in any attempt to examine the ramifications of the international mining world. It stretches from the United Kingdom across Spain into Africa and over the Atlantic into Canada and the U.S.A., with forays into Germany, Belgium, Austria, Australia and elsewhere. The hands of Anglo American Corporation, Consolidated Zinc Corporation and world-embracing aluminium groups are firmly clasped within it, and representatives of the Congo combination of companies adorn the directorates which bear such aristocratic names as Rothschild and Cavendish-Bentinck.

Though its original interests were mining pyrites in Spain, the Rio Tinto Co. Ltd. was registered in London in 1873. Keeping up with the times and the general trend towards combination and monopoly, the company underwent certain changes. Its directors were among the most fervent supporters of General Franco at the time of the Spanish Civil War. This devotion to the Caudillo’s cause undoubtedly prospered them so that, together with their associates in the wider financial sphere, they have been able to spread their tentacles through the zinc and aluminium industry into the precious metals and general metals’ fields. In 1954 Rio Tinto transferred its Spanish assets to a company which it formed in Spain with a capital of 1,000,000,000 pesetas, under the title of Companhia Espanhola de Minas de Rio Tinto S.A. For this worthy proof of its sensitiveness to Spanish patriotism, it received a compensation of 36,666,830 pesetas in settlement of profits accumulated up to 1 January 1954, and all the 333,333 ‘B’ shares of 1,000 pesetas each in the new company. Additionally it was awarded a sterling payment of £7,666,665. Rio Tinto still draws a retainer as provider of technical and commercial services in London for the Spanish company, in which its holding of all the ‘B’ shares still gives it a direct interest.

Rio Tinto is now an investment holding company, whose financial operations have brought it into the forefront of industrial entrepreneurship. Africa is well up among its spheres of activity, its most important holdings on the continent being in Rhokana Corporation and Nchanga Copper Mines, where, as we have seen, it is associated with the British South Africa Co., Anglo American Corporation, Union Corporation, Tanganyika Concessions, Union Minière and Rand Selection Trust in their holdings in the important Rhodesian and South Africa mining and industrial ventures.

So tortuous and incredibly expansile are the links that tie the groups exploiting Africa’s resources with those enriching themselves in other corners of the earth that we should find nothing remarkable in being led back from Rio Tinto in Africa, via some of the most powerful American and British financial forces, into Rio Tinto in Canada.

One of the most lively motivating springs of monopoly is to forestall in new or unexplored areas the entry of rival groups, and where this proves abortive or impossible, to collaborate with them. We shall see in a later chapter how Canadian Eldorado forced Union Minière to bring down the price of uranium and how their interests lock through Sogemines representation on the former’s board. In the world of Western free enterprise, competition is being eroded by monopoly’s role of the lone ranger after undivided profits.

Thus are African riches brought to support the manipulative ramifications of international finance-capital. Between Société Générale and Rio Tinto there is interposed a solid phalanx of interwoven power that moves out stealthily across the world.

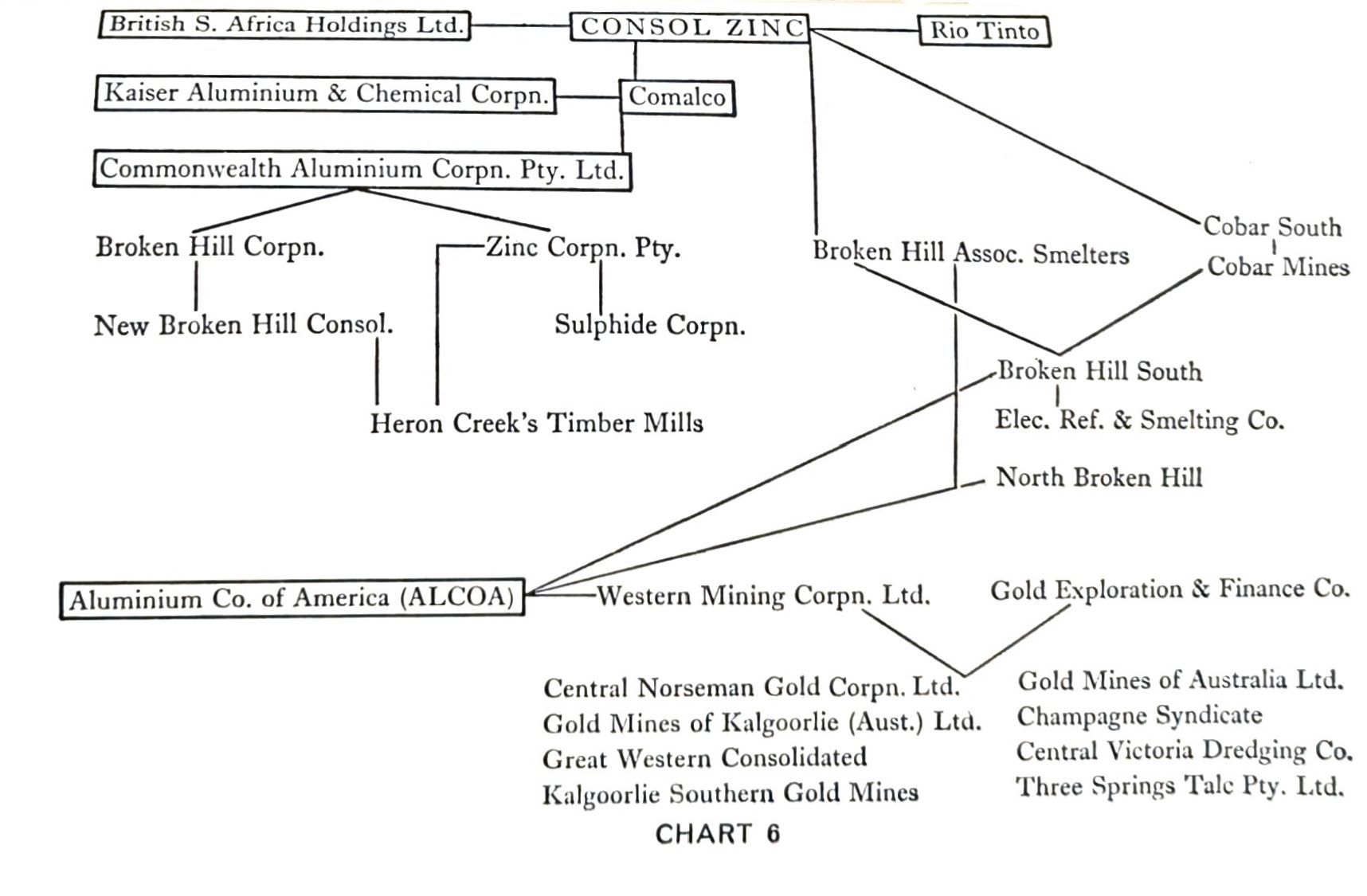

Breaking into the aluminium world, Rio Tinto formed an alliance with Consolidated Zinc Corporation Lt. This merger appeared superficially to bring together two powerful groups having no joint leading strings. This ostensible separation would mislead only the ignorant. Its subterfuge is immediately destroyed by a single glance at its combined directorate, which at once shows up the connections with South African mining and financial interests. P. V. Emrys-Evans is a prominent member, and the Rt. Hon. Lord Baillieu, K.B.E., C.M.G., deputy chairman. Lord Baillieu is also deputy chairman of the Central Mining and Investment Corporation Ltd., a leading investment and finance house within the Anglo American group of companies directed by Harry F. Oppenheimer and C. W. Engelhard. Mr Emrys-Evans is also important in his own right, being vice-president of the British South Africa Co. and a director of Anglo American.

However, the connection goes further than that. British South Africa Holdings Ltd., and some of its associates, under an agreement dated 7 December 1960, subscribed £10 million to Consolidated Zinc in the form of 5 1/2 per cent loan stock in return for options to acquire 2,285,714 ordinary shares of £1 each in Consolidated Zinc at a price of 87s. 6d. a share. Here we enter into the intricate maze of aluminium financial policies into which Consolidated Zinc has made deep incursions by its alliance with the Kaiser Aluminium & Chemical Corporation in Commonwealth Aluminium Corporation (Pty) Ltd., commonly known as Comalco. The options acquired by British South Africa Holdings can be exercised any time between 1 June 1966 and 1 July 1968 or the date on which Commonwealth or its associated operating companies have produced a total of 200,000 long tons of aluminium ingots in the proposed new refinery to be erected by Comalco, whichever is the later.

Kaiser Aluminium’s principal interest is in its wholly owned Kaiser Bauxite Co., Jamaica. In addition to its mining activities, Kaiser operates processing and chemical plants in the United States and Canada and has investments in aluminium, mining, reduction and fabricating facilities and marketing industries in the United Kingdom, South America, Africa and Asia. It operates through two fully owned subsidiaries: Kaiser Aluminium & Chemical Sales Inc. and Kaiser Aluminium International Corporation. Like Reynolds Metals, Kaiser Aluminium only broke into the United States aluminium industry under the impetus of wartime demands for aircraft metal. Before the second world war, Aluminium Co. of America – ALCOA – was the sole domestic producer of primary aluminium.

Consolidated Zinc, with an authorised capital of £25 million, has extensive interests which make it a formidable controller of a number of important metals and allied chemical products. Formed less than fifteen years ago, in February 1949, its purposes were ‘to develop, extend and carry on or finance, either itself or through any of its subsidiary or associated companies, the development, extension and carrying on of the lead and zinc mining and other or raw material producing industries and the smelting, refining and manufacturing and other industries associated therewith, throughout the world, and particularly in the Commonwealth’.

All this apparently has no connection with Africa, but we have only to look at some of the directorates to discover immediately how close the links are with the Oppenheimer network and the financial groups that associate with it.

Such are the mammoth gold-clad interests that are behind the Consolidated Zinc-Rio Tinto merger. The new holding company, Rio Tinto-Zinc Corporation Ltd., was created by a financial operation that gave shareholders of Consolidated Zinc fifty-eight ordinary shares of ten shillings each in the new company in exchange for every twenty shares of £1 in Consolidated Zinc. Rio Tinto stockholders received forty-one shares of ten shillings each in the new company for every twenty ordinary stock units of ten shillings held in Rio Tinto. Preference shares in both companies were also exchanged for preference shares in the new one.

The merger brings Rio Tinto-Zinc well into the forefront of the aluminium field, accentuating its already important position in the zinc-lead and non-ferrous metals field. It brings Consolidated Zinc more fully into the sphere of mineral exploitation in Africa by reason of Rio Tinto’s holdings in some of the principal concerns operating in South Africa, Rhodesia and elsewhere. The connections with the American, Canadian and Australian industrial and financial scenes are apparent from the foregoing very brief review. Through these interests, the Rio Tinto-Zinc combine has additional strings which lead back again to Africa.

There are some rare and localised non-metallic materials which are used in basic and secondary industries. These include asbestos, corundum, mica, vermiculite, phosphate rock, gypsum, mineral pigments, fluorspar, and silica. The most important is asbestos. It is found in three principal fibres; chrysolite, crocidolite or blue asbestos, and amosite. All three fibres have certain common characteristics. They are all non-inflammable, non-conductors of heat and electricity; they are practically insoluble in acids and are capable of being spun into textiles.

It is slight differences in these qualities that give them different uses. Chrysolite is the most resistant to fire, and its strong, fine flexible texture makes it highly suitable for asbestos textiles and for use in brake linings, clutch facings and insulation fittings. It is used also for asbestos boards and asbestos cement products. Blue asbestos has greater tensile strength and resilience, and though not so resistant to fire, withstands acids and sea-water better. It is used chiefly in the manufacture of filter cloth, boiler mattresses, insulation packings and asbestos cement products. Amosite has a fibre length of three to six inches and has greater resistance to heat than crocidolite and greater resistance to sea-water than blue asbestos. These qualities make it particularly suitable for use in spun materials and aircraft. South Africa is at present almost the only place in which both blue asbestos and amosite are found. Canada is the greatest producer of chrysolite; South Africa and Rhodesia are far behind.

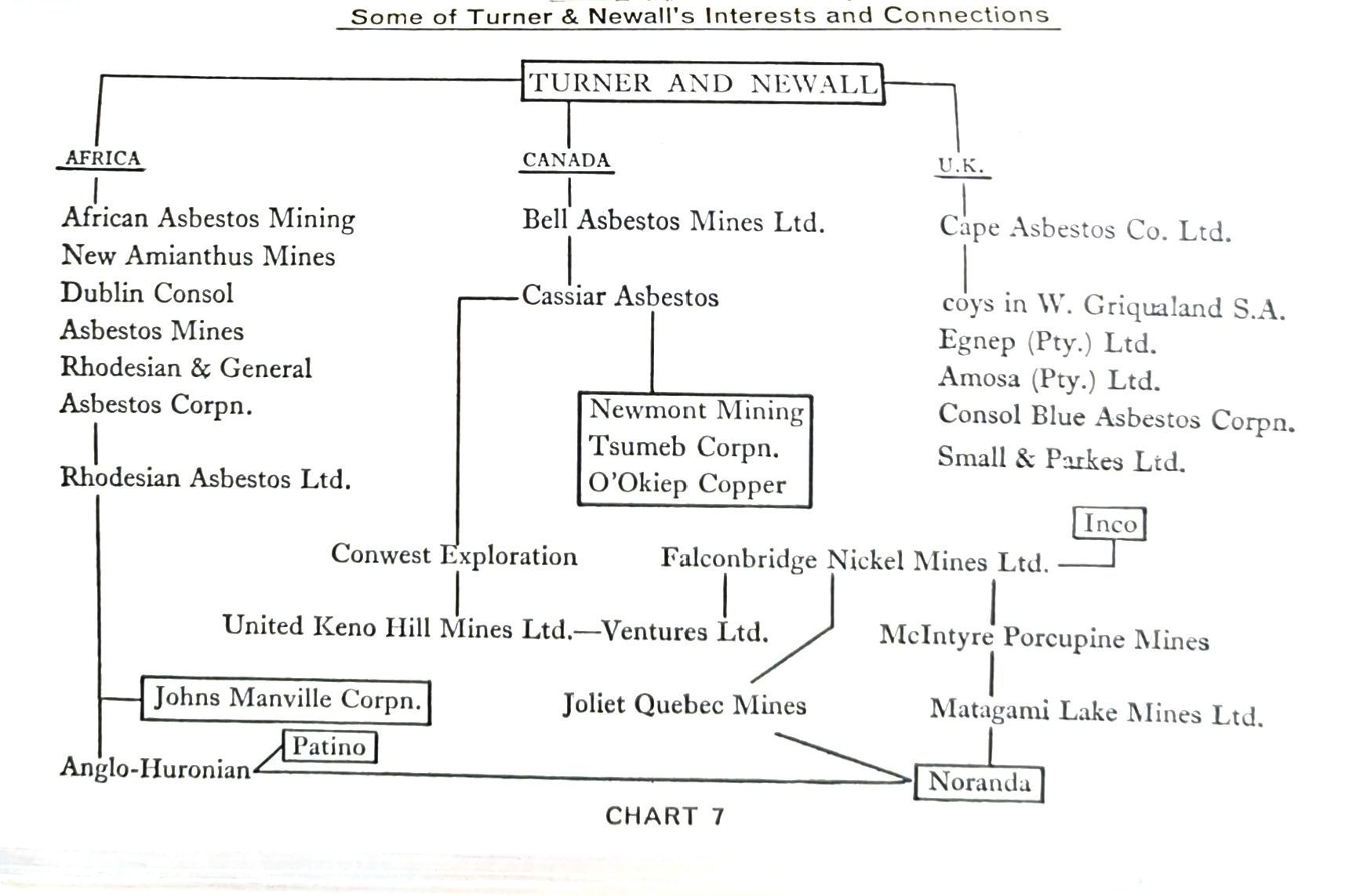

The South African deposits are mainly in Swaziland and Eastern Transvaal. They are in the virtual control of a British firm, Turner & Newall Ltd., registered in 1920, which has in its hands 90 per cent of the British asbestos trade. This fact enabled it to secure an agreement in 1930 with the Soviet Union regulating deliveries to the continental market. An important producer of high grade chrysolite, the Soviet Union ceased export after the last war.

Superficially unimposing, Turner & Newall’s board has as its chairman Ronald G. Scothill, who is associated with the insurance world as director of Liverpool and Globe Insurance Co. Ltd. and Royal Insurance Co. Ltd., and with finance as director of the District Bank. Its capital, however, is impressive, being authorised at £60 million with almost £50 million paid up. Originally £3 million, the increase in the size of the company’s capital gives an indication of the growth of its dominance of asbestos mining and allied industries.

This capitalisation becomes more articulate when it is related to the sweep of the Turner & Newall asbestos kingdom, which is rooted in African and Canadian mines. A holding company, it has a network of subsidiaries throughout the world which manufacture and sell asbestos, magnesia and connected products. See Chart 7.

A recent survey reveals that some 60 to 70 per cent of the world’s total business activity is controlled by less than 2 per cent of all the companies in the world. The colossal Unilever Trust is a perfect illustration of this monopolistic ratio of control.

For millions of housewives there is no such thing as a corporate entity called Unilever. There is just the daily routine of choosing between Lifebuoy and Lux, Pepsodent and Gibbs, Orno and Surf – or buying Lipton’s tea, Wall’s sausages and Bird’s Eye frozen foods, Flytox, Stork margarine and Harriet Hubbard Ayer’s cosmetics. From the viewpoint of the tax-collector also, Unilever is still not a corporate entity but two separate companies, ‘Unilever Limited’, the British Company, and ‘Unilever N.V.’, the Dutch company. It has subsidiaries throughout Europe, in Belgium, Austria, Denmark, Germany, Finland, Italy, Sweden and Switzerland. In all these countries it tends to control the production of soups, frozen foods, soap, margarine, insecticides, detergents, cosmetics and edible oils. It has also powerful and century-old interests in Latin America, west, central and South Africa, India, Ceylon, Malaysia, Trinidad, Thailand and the Philippines.

Unilever’s most robust offshoot overseas is the United Africa Company, through which the Trust became known as the ‘uncrowned King of West Africa’. The United Africa Company is the world’s largest international trading company, and contrary to the belief that the liberation of colonial territories would automatically suppress monopoly capitalism, the Unilever empire continues to flourish. This is because it has known how to adapt its policy to the ‘challenge of the times’, as a company report puts it. And so, Unilever is applying its profit-making objectives to other more yielding sectors. It has accelerated its withdrawal from the West African merchandise and produce trade to concentrate on development in cars, engineering and the pharmaceutical sides of the business. The neo-colonialist aim is not only to export capital but also to control the overseas market. Thus attempts are subtly made to prevent developing countries from taking any decisive steps towards industrialisation, since the exploitation of the indigenous expanding market is not the prime objective. If the attempts to prevent industrialisation fail, then at all costs the Trust must secure a participation in a development it cannot prevent. And by its very nature this participation thwarts any further progress since it ensures a regular flow of payments into the coffers of monopoly capital in the form of royalties, patents, licensing agreements, technical assistance, equipment and other ‘services’. It also gives priority to the assembling and packaging of foreign products often presented under the false labels of indigenous concerns. Unilever’s present emphasis on the packaging industries is also no coincidence.

The up-to-date Trust relies less on the amount of the dividends than on certain clauses in the Company agreements which make indigenous capital dependent on monopoly capital for the renewal of contracts and for the allocation of funds. It is significant that in a recent issue of the New Commonwealth, the United Africa Company has been referred to as the ‘gentle giant’. Monopoly methods have become more subtle, but Lever’s famous statement still seems to hold true: ‘Afterall we are working for the permanent interests of Britain’.