Neocolonialism byKwame Nkrumah 1965

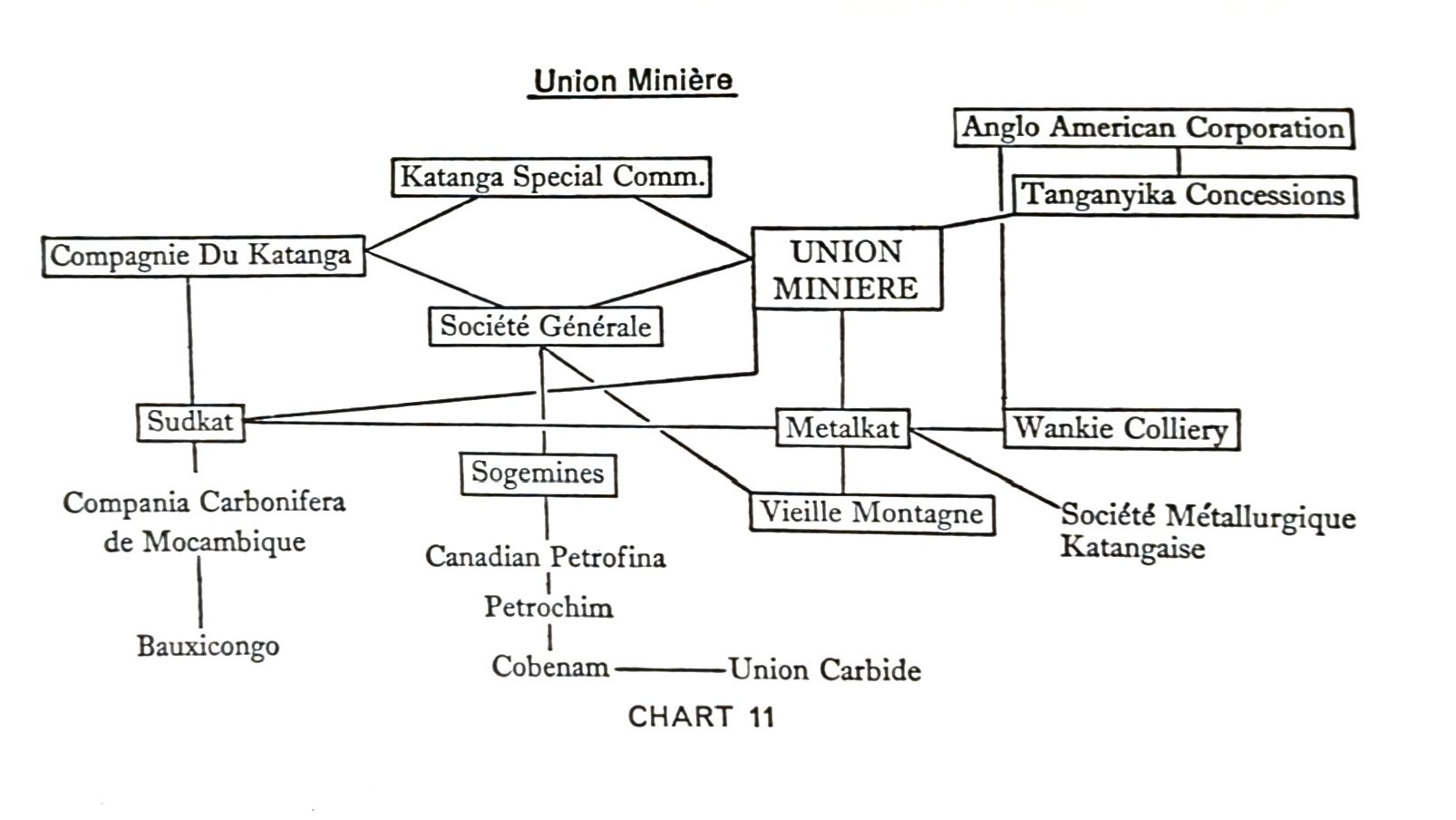

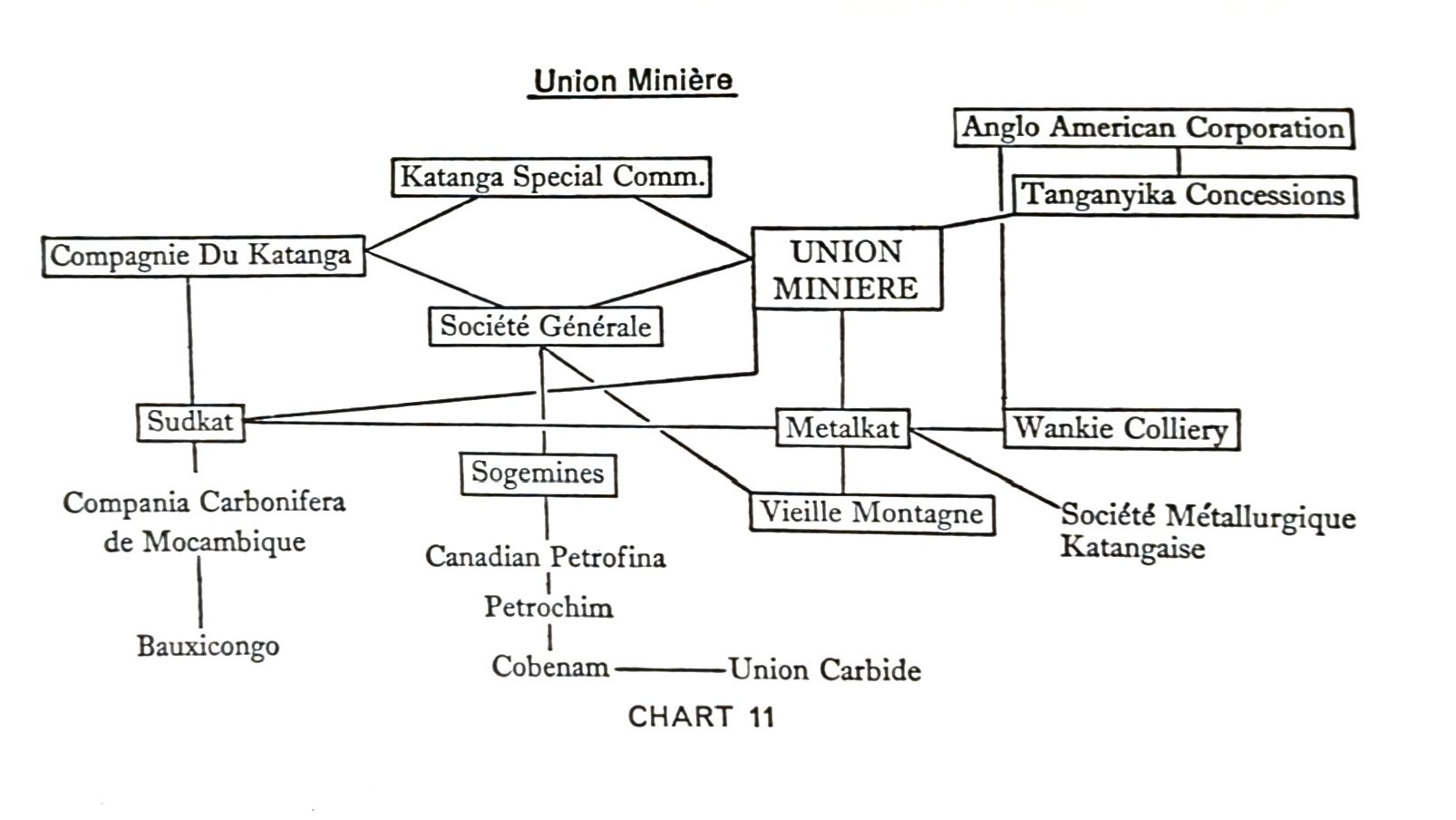

THERE is perhaps hardly an industrial organisation in the world that has been so widely publicised over the past five years as Union Minière, because of the ducks and drakes it has played with the establishment of Congo independence and unification. This great mining company has been since Congo’s independence the bone of contention between the Congolese government and the secessionist Katanga Province. Principally owned by small shareholders, its control rested with Belgian and British financiers.

The largest block of stock in the company, 18·14 per cent of the 1,242,000 shares, which formerly belonged to the Belgian colonial administration, passed at independence to the Congolese government, and was held in trust by the Belgian government for a time, pending the settlement of political problems. In November 1964, Moise Tshombe who had by then returned from exile to become Congolese Prime Minister, published a decree which had the effect of transferring control of Union Minière from Belgian banking and other interests to the Congolese government without compensation. The decree gave the Congolese government the entire portfolio of 315,675 shares in Union Minière held by the Comité Special du Katanga, a concession-granting concern, two-thirds of which is owned by the Congolese government and one-third by Belgian interests.

The Belgian government considered that 123,725 of these shares belonged to the Compagnie du Katanga which is an off-shot of the Société Générale de Belgique. The effect of the decree was to reduce the voting strength in Union Minière of the Société Générale and its associate, Tanganyika Concessions Ltd. from 40 per cent to less than 29 per cent, while the Congolese government’s votes were raised from nearly 24 per cent to nearly 36 per cent. This meant that in any policy dispute the Belgians would have to rally the support of the small shareholders comprising about 36 per cent.

For weeks the Belgian government and the Congolese government talked of arranging meetings to discuss the situation. Each had a trump card. The Belgian government held the entire portfolio in trust, while the Congolese government’s strength lay in the expiration of Union Minière’s lease in 1990.

On 28 January 1965, Tshombe arrived in Brussels for talks with the Belgian Foreign Minister, M. Spaak. He asked for the immediate handing over of the portfolio of shares valued at £120 million. These included 21 per cent of the voting rights in Union Minière. The Belgians, on the other hand, demanded compensation for Belgian property damaged in the Congo troubles, and for chartered companies who lost mineral concessions under the November decree. They also insisted that the agreement should cover the interest payable on defaulted Congo bonds.

After days of hard bargaining, Tshombe scored what appeared to be a great triumph. He secured the £120 million portfolio of shares, and also received a cheque from Union Minière for £660,000 representing royalties and dividends on the Congo’s 210,450 shares in Union Minière, which gave it 24 per cent of the voting rights in the company. With this diplomatic victory he returned to Leopoldville, his hand strengthened to deal with the continuing political and military problems of the country. Since then he has had cause to wonder just how much of a victory he achieved.

In my address to the Ghana National Assembly on 22 March 1965, I gave details on the Congo situation:

‘In the five years preceding independence, the net outflow of capital to Belgium alone was four hundred and sixty-four million pounds.

When Lumumba assumed power, so much capital was taken out of the Congo that there was a national deficit of forty million pounds.

Tshombe is now told the Congo has an external debt of nine hundred million dollars. This is a completely arbitrary figure – it amounts to open exploitation based on naked colonialism. Nine hundred million dollars ($900,000,000) is supposed to be owed to United States and Belgian monopolies after they have raped the Congo of sums of £2,500 million, £464 million, and £40 million. Imagine what this would have meant to the prosperity and well-being of the Congo.

But the tragic-comedy continues. ... To prop up Tshombe, the monopolies decided that of this invented debt of $900 million, only $250 million has to be paid. How generous, indeed!

Bonds valued in 1959 at £267 million, representing wealth extracted from the Congo, are to be returned to the Congo after ratification by both parliaments. But the monopolies have decided that the value of the bonds is now only £107 million. So the profit to these monopolies is a net £160 million.

The monopolies further announced a fraudulent programme to liquidate so-called Congolese external debts of £100 million. Upon announcing this, they declare Congo is to be responsible for a further internal debt of £200 million.

In plain words, they are depriving the Congolese people of another £100 million. And they call this generosity!

We learn that the monopolies have declared a further burden for the suffering people of the Congo: an internal debt of £200 million on which the Congo must pay additional compensation of £12·5 million to Belgian private interests.

Beyond this, a joint Congolese-Belgian organisation has been formed. It is withdrawing old bonds and replacing them with forty-year issues valued at £100 million. These will pay interest at 4 per cent per annum.

Note this: as the old bonds are worthless, the new organisation must pay all interest on the old bonds from the 1960-65 to the monopolies and EACH HOLDER OF THE WORTHLESS OLD BONDS must be given a new bond for every old one. In short, the organisation is a device to take more, to enrich the monopolies further and to defraud the suffering people of the Congo.

Tshombe has promised not to nationalise investments valued at £150 million and to retain 8,000 Belgians in the Congo. He has set up an Investment Bank to manage all portfolios. The value is placed at £240 million. It is controlled by Belgians.

In one year, Union Minière’s profits were £27 million. But although the national production in Congo increased 60 per cent between 1950 and 1957, African buying power decreased by 13 per cent. ... The Congolese were taxed 280 million francs to pay for European civil servants, 440 million francs for special funds of Belgium, 1,329 million francs for the army. They were even taxed for the Brussels Exhibition.

Despite political independence, the Congo remains a victim of imperialism and neo-colonialism ... (but) the economic and financial control of the Congo by foreign interests is not limited to the Congo alone. The developing countries of Africa are all subject to this unhealthy influence in one way or another.’

If this quotation appears to contain much detail, the newly independent peoples and their leaders have no more urgent task today than to burn into their consciousness exactly such detail. For it is such material that makes up the hard reality of this world in which we are trying to live, and in which Africa is emerging to find its place.

The full significance of the part played by Union Minière in Congolese affairs can only be understood if an examination is made of the interests involved in this powerful company. Nearly all the large enterprises engaged in exploiting the manifold riches of the Congo come within its immediate embrace or have indirect relations with it. THey do not, however, complete the extent of the company’s engagements. Its connections with leading insurance, financial and industrial houses in Europe and the United States are shown in the following list, as well as its connections with the Rhodesian copperbelt:

Compagnie Foncière du Katanga.

Société Générales des Forces Hydro-electriques – SOGEFOR.

Société Générale Africaine d'Electricité – SOGELEC.

Société Générale Industrielle et Chimique de Jadotville – SOGECHIM.

Société Métallurgique du Katanga – METALKAT.

Minoteries du Katanaga.

Société de Recherche Minière du Sud-Katanga – SUDKAT.

Ciments Métallurgiques de Jadotville – C.M.J.

Charbonnages de la Luena.

Compagnie des Chemins de Fer Katanga-Dilolo-Leopoldville – K.D.L.

Société Africaine d'Explosifs – AFRIDEX.

Compagnie Maritime Congolaise.

Société d'Exploitation des Mines du Sud-Katanga – MINSUDKAT.

Société d'Elevage de la Luilu – ELVALUILU.

Compagnie d'Assurances d'Outremer.

Société de Recherches et d'Exploitation des Bauxites du Congo – BAUXICONGO.

Exploitation Forestière au Kasai.

Centre d'Information du Cobalt.

Société Générale Métallurgique de Hoboken.

Société Anonyme Belge d'Exploitation de la Navigation Aeriènne – SABENA.

Société Générale d'Enterprises Immobilière – S.E.I.

Compagnie Belge pour l'Industrie de l'Aluminium – COBEAL.

Foraky.

Compagnie Belge d'Assurances Maritimes – BELGAMAR.

Société Auxiliaire de la Royale Union Coloniale Belge – S.A.R.U.C.

Wankie Colliery Co. Ltd.

Belgian-American Bank & Trust Co., New York.

Belgian-American Banking Corporation, New York.

Compagnie Générale d'Electrolyse du Palais S.A., Paris.

Trefileries et Luminoire du havre S.A., Paris.

Société Belge pour l'Industries Nucleaire – BELCO NUCLEAIRE.

Tanganyika Concessions is one parent of Union Minière du Haut Katanga. The other was the Katanga (Belgian) Special Committee. Union Minière was formed between them for the stated purpose of bringing together the interests of both organisations in the mineral discoveries Tanganyika Concessions had made under a concession granted to it by the Committee in the Katanga province of the Congo. The concession, which has until 11 March 1990 to run, covers an area of 7,700 square miles, containing rich copper as well as zinc, cobalt, cadmium, germanium, radium, gold, silver, iron ores and limestone deposits. Included is a tin area of some 5,400 square miles.

Ores mined are processed at a number of plants, passing through smelting and concentration stages. Hydro-electrical energy is supplied from four main power plants, one of which was installed by a subsidiary of Union Minière, the Société Générale des Forces Hydro-electriques. Three others belong to Union Minière itself. These three plants are connected to a distribution network, part of which is devoted to supplying electrical power to the Northern Rhodesian copperbelt at the rate of 600 million kw. Per year. Part of this network is owned by the Société Générale Africaine d'Electricité – SOGELEC – in which Union Minière has a substantial interest. The company’s plants at Elizabethville, Jadotville, Kolwezi and Kpushi consumed 76 million kw. In 1962, during which year certain damages caused to the installations in December 1961 were completely repaired.

Most of the concerns in which Union Minière is interested are supported by the Société Générale de Belgique. Man also have connections with Anglo American Corporation either direct or by way of Tanganyika Concessions and Union Minière and their subsidiaries. Société Générale has a direct holding of 57,538 shares out of the 1,242,000 shares of no nominal value that constitute the authorised and issued capital of frs. 8,000,000,000 of Union MInière. Other principal shareholders are the Katanga Special Committee and Tanganyika Concessions. Royalty on the concession is paid to the Katanga Committee by way of a sum equivalent to 10 per cent of any dividend distributed over and above a total of frs. 93,150,000 in any year. Tanganyika Concessions, by agreement with the Committee, shares in this special benefit to the extent of 40 per cent. Originally incorporated in the Congo, the company took its seat of administration and all its funds to Belgium during 1960, when the Congo was achieving independence and needed the support of those who, over the years, had drawn such heavy tribute from it.

Société Générale’s patronage hangs closely over Union Minière. Attached to the Katanga Special Committee is the Compagnie du Katanga. The Katanga Company is within the group of the Compagnie du Congo pour le Commerce et l'Industrie – C.C.C.I. – constituted in 1886 when Leopold II was creating his personal empire in the Congo. It was on the initiative of one of Leopold’s swashbucklers, Captain Thys, that C.C.C.I., according to the chairman of the Société Générale, became the first Belgian enterprise established in the heart of Africa. His name is attached to the repair station of the first railway from Matadi to Leopoldville. Thysville is now an important link in the railway system, and C.C.C.I., in the words of Société Générale’s chairman, has since its inception been connected directly or through its affiliates, with all sectors of economic activity in the Congo by the creation of transport enterprises, agricultural industries, cement works, construction and building concerns, property companies, food industries, as well as commercial firms. The company has, affirmed the chairman, ‘contributed to endow the Congo with an equipage which places the country in the first ranks of the black African states’.

Several of these interlinked enterprises are included in the list of Union Minière’s interests, which frequently join those of Société Générale. Thus Société Générale Métallurgique de Hoboken, a company in which Société Générale owns 50,000 shares of no par value, processes certain semi-finished products from the Union Minière mines for the market in finished metals of high purity and individual specification. In conjunction with the Fansteel Metallurgical Corporation of Chicago, hoboken created a joint subsidiary, Fansteel-Hoboken, in December 1962, with a capital of 360 million francs. This new company will produce refractory metals, notably tantalum, columbium, tungsten and molybdenum, in various marketable forms.

Wankie Colliery Co. Ltd. represents Union Minière’s participation in Southern Rhodesia’s coal mines. While its shareholding is not unimportant, Anglo American Corporation predominates and acts as the company’s secretary and consulting engineers. Capitalised at £6,000,000, of which £5,277,810 is paid up, the company owns coal-mining rights over 42,000 acres and surface rights over about 29,000 acres of land in the Wankie district of Southern Rhodesia. The means by which the mining interests dominate the government of the ‘settler colonies’ are many, but the manner in which land is given away by the administration and then leased back from the buyers or lessees exhibits some of the most unashamed and open gerrymandering possible. Thus Wankie Colliery obtained a long-term lease by agreement with the Rhodesian government surface rights to 26,000 acres of land additional to the above-mentioned stretches, in return for which Wankie has graciously leased some 4,000 acres of surface rights in its original landholdings to the government.

A directorial link, M. van Weyenbergh, associated Wankie Colliery with Société Métallurgique du Katanga – METALKAT – a subsidiary of Union Minière, founded in Belgium in 1948 in conjunction with S.A. des Mines de Fonderies de Zinc de la Vieille-Montagne to construct at Kolwezi a plant capable of producing 50,000 tons of electrolytic zinc annually from concentrated provided by Union Minière’s Prince Leopold mine. The Metalkat plant produces zinc, cadmium and refined copper. With a capital of frs. 750,000,000 represented by 150,000 shares of no par value, the company made a net profit of frs. 160,831,393 in 1961, after providing for various liabilities, among which dividends accounted for frs. 120,000,000 (almost three-quarters of net profit) and directors’ percentages frs. 7,857,517.

Union Minière’s partner in Metalkat, Vieille-Montagne, is one of the big European mining concerns producing zinc, lead and silver. A Belgian company, founded in 1837, it has silver-lead-zinc properties in Belgium, France, Algeria, Tunis, Germany and Sweden and metallurgical works in Belgium, France and Germany. Of the 405,000 shares of no par value constituting its capital of frs. 1,000,000,000 Société Générale owns 40,756. Its accounts for the year ended 31 December 1961 showed a net profit of frs. 143,287,506, after various provisions, of which the largest was for re-equipment, amounting to frs. 100,000,000. Dividends took frs. 101,250,000 and taxes thereon frs. 27,700,000. Directors’ percentages took frs. 14,327,760. Legal reserves seem to account for considerable sums which these large companies set aside. This item was credited with frs. 100,000,000 in Vieille-Montagne’s 1961 accounts.

The Compagnie du Katanga, like Union Minière, attached to the Katanga Special Committee, joined Union Minière in creating in the Congo in 1932 the Société de Rocherche Minière du Sud-Katanga – SUDKAT. Both Compagnie du Katanga and Union Minière had interests in a large area adjacent to the latter’s properties which they decided to combine. With Congolese independence, control of Sudkat as well as its funds were transferred to Belgium. Copper deposits at Musoshi and Lubembe and zinc-lead-sulphur ore bodies at Kengere and Lombe owned by Sudkat were transferred to the Société d'Exploitation des Mines du Sud-Katanga – MINSUDKAT – formed in the Congo in June 1955, with a capital of Congolese frs. 50,000,000.

Sudkat holds interests in the Companhia Carbonifera de Mocambique, concerned with coal mining, as well as in Bauxicongo and Metalkat. Metalkat created a local company in 1962, the Société Métallurgique Katangaise, with a capital of 600 million francs represented by 150,000 shares, to which it transferred its Katanga installations. The zinc ingots produced are being processed by Metalkat.

One of Sudkat’s most important investments is in Sogemines Ltd. This company, though registered in Montreal and operating in Canada, is so intimately connected with the Société Générale that it has on its board six of the Société’s directors, two of whom are also on the Union Minière directorate. Société Générale’s investment in Sogemines covers 259,250 preferred shares of $10 each and 1,281,250 ordinary shares of $1 each, representing over one-fifth of the Canadian company’s issued capital. A wholly owned subsidiary, Sogemines Development Co. Ltd., is carrying out exploration work in various parts of Canada and holds minority interests in other mining enterprises. Sogemines Ltd. is an investment and holding company participating in mining, oil and industrial ventures. L. C. and F. W. Park in The Anatomy of Big Business, graphically make the point that its ‘relationships between Canadian and Belgian capital are based on the alliances that operate both in Belgium or the Congo and in Canada’. (p. 157.)

Sogemines’ parent, Société Générale, devotes considerable space in its annual report to the former’s operations. The most important concern in which they are interested is Canadian Petrofina Ltd. In 1961, Canadian Petrofina made the record profit of $5,516,926. Petrofina is a Belgian oil company with international associations, especially in the new African States, both inside and outside the oil industry. Its connections with Société Générale are not limited to shareholdings and directorial interlocking. Associations are maintained with several leading banks, including the Banque Belge, the Banque de l'Union Français, the Credit Foncier de Belgique, the Banque de Paris et des Pays Bas, and a number of insurance companies.

Under the impetus of Société Générale and certain associates, a subsidiary of Petrofina, Société Chimique des Derives du Petrols – PETROCHIN – underwent a financial reorganisation during 1962, when certain assets were passed to it, principally by Petrofina. Société Générale used the opportunity to make a participation of 29 million francs to the company’s capital, ‘in which several other enterprises within its group equally own interests’. Société Générale’s shareholding is 58,000 shares of no par value. Cobenam, a joint venture of Petrochim and Union Carbide, brings together the banking interests of Société Générale with those interested in the great American chemical corporation, the Continental Insurance Co. and the Hanover Bank, which is involved with Anglo American Corporation and the banking consortia now engaging themselves in ventures in the new African States. There is some Rockefeller influence in the Hanover Bank, and it is linked by financial interchanges with the American Fore group of New York, a principal fire and casualty insurance company.

Union Carbide & Carbon manufactures enriched uranium, and through the influence of its direct backers, Hanover Bank, and indirect associations with the Rockefeller-Mellon group, has become the major contractor to the government-owned atomic energy plants at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Paducah, Kentucky. For this purpose a separate division was formed, Union Carbide Nuclear Company, uranium and vanadium mines being worked in Colorado, and a tungsten mine and mill in California. Union Carbide’s range of interests in the chemical sphere is wide, it having a very large synthetic materials sector. A Canadian subsidiary of Union Carbide is Shawinigan Chemicals, which it half owns in company with Monsanto Chemical Co. and Canadian Rosins & Chemicals Ltd. An affiliate, B. A.-Shawinigan Ltd., is owned by British American Oil, connected with the Bank of Montreal and Mellon. Shawinigan Chemicals has several subsidiaries which are equally controlled with U.S. companies. Société Générale has its own nuclear concern, Société Belge pour l'Industrie Nucleaire – BELGO NUCLEAIRE – in which we have noted Union Minière’s interest.

This is only a single short strand of the tangled web that relates predominant banking interests in Europe and America to industrial undertakings in Africa and other parts of the world. It gives only the barest indication of the elastic character of these interests.

The incursions of Société Générale into the oil world are not confined to Petrofina and its associates. Petrobelge, another company carrying out prospecting in the north of Belgium in association with the Société Campincise de Recherches et d'Exploitations Minerals, has an affiliate operating in Venezuela, Petrobelge de Venezuela. Petrobelge is linked with Petrofina and the Bureau de Recherches et de Participations Minières Marocain in prospecting in Morocco, the first stages of which will be completed in 1963. Italy is another scene of Petrobelge’s activities, where in collaboration with the Italian company, Ausonia Mineraria, and the French organisation, Société Française de Participations Petrolières – PETROBAR – it is investigating hydrocarbons in the concessions obtained by Ausonia. In addition, Petrobelge has associated itself with an Italian-French-German consortium in a venture prospecting seismic regions on the Adriatic coast. Both Petrobelge and Petrofina have got together with the Spanish company, Ciepsa, to prospect for hydrocarbons within a concession owned by Ciepsa.

Direct links with Belgium’s military programme and, accordingly, with that of NATO, are closely operated through the Poudreries Réunies de Belgique, whose capital was increased during 1962 from 203,900,000 francs to 266,700,000 francs. At the beginning of the year it absorbed the Fabrique Nationale de Produits Chimiques et d'Explosifs at Boncelles, Belgium, whose purchase included a participation in the capital of S.A. d'Arendonk. The acquisition of the latter’s selling organisation has added to the scope of the company’s civil activities. These Belgian concerns are linked with the Société Africaine d'Explosifs – AFRIDEX – in which Union Minière has interests. The military and nuclear interpenetration gives a special emphasis to the uranium output of the Union Minière complex, which in the post-war years upheld the Belgian economy and helped it to refurbish its industrial equipment. Out of the Congo came the spoils that provided for the further exploitation of the territory and the high productive ratio the lately devastated war-ridden and Nazi-occupied country attained so swiftly. Even before the second world war, uranium was already making the Shinkolobwe mine a very important asset to Union Minière and the Belgian government. As one writer puts it, ‘The Union Minière achieved a certain notoriety in the ‘twenties and ‘thirties by obliging would-be purchasers of radium to pay $70,000 a gram, until competition from the Canadian Eldorado company forced the price down to a mere $20,000 a gram, a level at which both companies were able to amke a profit’ (Anatomy of Big Business, p. 156). According to the calculation of experts, Union Minière’s profits were estimated to be three billion francs a year, $60 million in terms of American currency, and over £20 million in sterling.

In spite of the disturbed situation in Katanga and the protests of the company that their business had been seriously impeded, Union Minière’s balance sheet for the year ended 31 December 1960 showed a net profit of frs. 2,365,280,563. Dividends absorbed no less than frs. 1,863,000,000, rather more than half the net profits, carrying a dividend tax which went to the Belgian government of frs. 381,578,313. Emoluments to directors, auditors and staff fund (for Europeans) absorbed frs. 84,609,333, while Permanent Committee members received frs. 7,111,567.

Eldorado Mining & Refining Ltd. is by no means independent of the big business and financial interests which have Canada’s industry in their grip, and whose associations with Africa and other less developed areas of the world are interwoven. A former private secretary to an ex-minister sits on its board, which is linked with Canadian Aluminium, whose directorate includes a former Governor-General of Canada. As we go along we shall see how these interlockings of international finance and exalted public figures and ‘the people’s representatives’ create an oligarchy of power pursuing and achieving their special interests, which have no relation whatsoever to ‘the public good’, with which they are made to appear synonymous. We shall find that the Royal Bank of Canada, represented on Eldorado’s board by W. J. Bennett, has connections with Société Générale and Union Minière through interlockings via Sogemines and prominent insurance and banking groups.

Wankie Colliery Co. Ltd., for instance, gives us M. van Weyenbergh, a director of Union Minière, Metalkat and Société Générale, several of whose directorial colleagues sit on Sogemines, whose chairman, W. H. Howard, besides being a vice-president of the Royal Bank and chairman of the Montreal Trust, is linked with the Rothermere newspaper group in Great Britain and is a director of Algoma Steel Corporation Ltd., which owns four coal mines in West Virginia and limestone and dolomite deposits in Michigan State. Algoma supplied the steel for the construction of a $20 million plant at Sault Ste Marie, Ontario, for the Mannesman Tube Co., a subsidiary of the Mannesmann steel company, which is a prominent member of the Ruhr industry of Western Germany. Mannesmann is said to be fast increasing its penetration into Canadian industry. Its board included representatives of the Deutsche Bank and Dresdner Bank, both of which are much in evidence in the consortia engaged in Africa and connected prominently with Anglo American Corporation. Chairman of Mannesmann since 1934 is W. Zanger, ‘a former member of the Nazi party and of the S.S.; he was one of the group of big German industrialists who financed the Nazi rise to power and provided the armaments for the Nazi war machine. In the days of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, Mannesmann opened short-lived affiliates in Kiev and Dniepropetrovsk’ (Anatomy of Big Business, pp. 109-110).

These are the forces that link with the South African, Rhodesian, Congo, Angolan and Mozambique mining magnates and industrialists, and we see them now entering the development projects of many of the new African States, hiding their identity behind government and international agencies, whose real character is at once exposed when their affiliations are carefully examined. They are the real directors of neo-colonialism.