Why Fascism? by Edward Conze and Ellen Wilkinson 1935

To say that ‘New Fascism is but Old Capitalism writ large’, that Fascism is the means by which Big Business throws off the last restraints of democracy, thinly disguising the process by Socialist phrases which would not deceive an intelligent baby, but which somehow managed to deceive millions of hard-headed Germans, has become the classic Socialist theory about Fascism.

In this country the theory has recently been expounded by Ernst Henri [1] in a rather fantastic, and by RP Dutt [2] in a more scholarly manner. This theory is correct as far as it goes. Fascism is used as an instrument by Big Business. But it puts Fascism in a more understandable perspective if it is seen as the political expression of the policy towards the masses of capitalism in adversity just as Social-Democracy mirrored the policy of capitalism to the masses in the hey-day of its prosperity.

Capitalism, as a system, is full of contradictions that tend inevitably to its self-destruction. It is of vital importance, therefore, to see the political parties which flourish in capitalist countries as a reflection of the vital economic contradictions. Social-Democracy showed these contradictions in their desire to increase wages and social services to a height which in time seriously diminish capitalist profit, at the same time desiring to keep on its feet a capitalism which could pay those wages. While capitalism was in a position to pay, however grudgingly, these improvements were conceded as the agreed price of the preservation of the capitalist system.

The time comes when capitalism is no longer able to pay this price. To maintain itself it must, as in Japan, secure new markets by imperialist expansion, or, as in England, it has to consolidate at a lower standard. Fascism reflects the new situation. But if it is to succeed it must embody both tendencies... the tendency towards Socialism which attracts the masses (and would if carried through destroy capitalism), and the tendency to preserve capitalism. For if it had no attractive quality for the masses, then though it might act in the short-term interest of individual capitalists, it could not serve the long-term interest of the capitalist class as a whole.

‘Anti-capitalist longing’, a German phrase which represents a condition of mind we also know in England, is one of the products of capitalism. The rival creeds, Social-Democracy, Communism, Fascism, from which the workers had to choose in Europe each only expressed part of this longing. The Communists did not shrink from the implications of their creed as did the Social-Democrats. They were willing to destroy capitalism, but they were not able to convince a sufficiently large proportion of the workers that they were capable of organising industry themselves.

Their technique of propaganda was as good as the Nazis’ at least up to 1931, which is why it is superficial to explain Nazi success as due to propagandist genius. But as the Communist political line became unreal, their technique degenerated. With Soviet Russia concentrating on building Socialism within its own borders, the Communist International could no longer form the basis of the world revolution which the Communists preached.

The Nazis provided an attractive alternative to Communism in this time of confusion by offering to give the workers an instalment of Socialism, while still preserving the economic order which paid them their wages, and which might, by prodding, be induced to employ more.

The Social-Democratic line became unreal because their internationalism prevented them from facing the logical consequences of their policy of demanding a bigger share of the product while preserving the capitalist system. To give what the Socialists demanded meant that German industry must get back its spheres of influence and colonial areas... and that in turn means war. Not that the Social-Democrats were wholly adverse to the idea. Their Chancellor, Hermann Müller, started the ‘pocket battleships’ and drilled the Black Reichswehr.

The Social-Democratic President of the Reichstag, Herr Loebe, smiled benevolently on the Verein für das Deutschland im Ausland which was paving the way in Austria and Czechoslovakia. But the Fascists were not hampered by even the vague pacifist international feelings of the Social-Democrats. They could go out whole-heartedly for war or for the demands that only war could secure, and thus claim that their line was the only real way to get back the German prosperity which would pay better wages, and so serve the long-term interests of both capitalists and workers.

On the basis of this contradiction, we must first discuss how far Fascism tends to preserve capitalism, and then examine those factors in Fascism which tend to go beyond capitalism and to destroy it.

That Fascism serves the ends of Big Business is seen in the attitude of Big Business men towards it. Both Mussolini and Hitler came to power only with their consent. Mussolini marched on Rome after the General Union of Industrialists (the Italian equivalent of the Federation of British Industries) had demanded that he should be Premier. A tax on wages, dismissal of ‘superfluous’ workers, wage reductions and large subsidies to the big concerns were the ways in which Mussolinian gratitude was immediately expressed.

Hitler became Chancellor after an historic breakfast with a Cologne banker, of the House of Levi, Oppenheim & Co, and Herr von Papen, a man with great industrialist possessions in the Saar, and a founder member of the Herrenklub, had set the seal of capitalist approval on the Nazis. When the Economic Council was set up it consisted exclusively of Big Business men, while to represent the workers the notorious Dr Ley was appointed. His fitness for that appointment may best be judged by his own speeches. We quote a gem from one of these:

The solution of the social question is much less a question of wages and still much less a question of paragraphs than of tact. Everything depends on whether the employers can show the necessary tact to their employees. And this tact arises out of the common voice of their blood.

The two proletarian leaders of the National Socialist Factory Organisation (NSBO) disappeared soon. One of them, Muchow, was ‘shot by accident’ in September 1933, while cleaning a revolver. Later, the other, Engel, was dismissed and replaced by an employer. The employers were solemnly declared to be ‘masters in their own house’, the ‘leaders’ of their ‘followers’, a state of affairs crystallised in the ‘leader law’. [3]

The workers elect a ‘representative council'... but from a list of suitable persons prepared by the Leader. This can only be elected or rejected en bloc. If the workers repeatedly reject the employers’ lists, a state official appoints the representatives of the workers. The leader bears the burden of moral responsibility for his workers, the workers, in return, owe loyalty to him.

The Babbitt-like emotion of Dr Ley is supposed to cast a warm glow over the hard fact that the general trend of Fascist industrial policy takes from the workers rights which they have won in a long and heroic fight. The right to strike and to organise in unions of their own choice stops at once. In Italy all strikes have been illegal in theory since 1926. Strikes of small dimensions, not involving many workers, are at times tolerated as a safety-valve for the day-to-day grievances, but this depends on the quite arbitrary decision of the local judges.

Strikes which extend to other factories, or are manifestations of solidarity with other workers on strike, or are expressions of political discontent, are quickly and brutally suppressed. What has been the case in Italy since 1926 was promptly followed in Germany from 1933. The Fascist leaders give the reason that the paralysing of parts of the economic system damages also the proletariat, which loses its wages and suffers from the decrease in national production.

The reasons given until now can only create a strong suspicion of the capitalist character of Fascism. A more deep-going proof has now to show that the trends of Fascist policy actually coincide with the two main trends of present-day capitalism – monopolism and imperialism.

Capitalist Monopolism and Fascism: In the modern political struggle between Socialism and capitalism centring round the fight for parliamentary control, the word ‘capitalism’ is frequently used as though it meant something like a political party, organised, static, with deliberate and consequently limited aims. Such a mechanical view makes a great deal of modern history unintelligible. Capitalism, like any other human system, is a living and therefore developing thing... full of contradictions, fighting hard and stubbornly for aims only partially understood by the capitalists themselves. Capitalism in an historical sense is not a rigidly-organised system of tyranny as represented in political perorations, but a phase in the history of mankind, a stage in its development. Fascism is the political expression of this present period of growth.

In the course of this development capitalism has undergone several radical changes in its structure, and each of these has inevitably meant a change in the political structure. In the first stage when capitalism was growing, but still had only conquered part of the feudal system, it needed some battering-ram to break down the feudal resistances to the rising capitalist class that wanted labour that was not bound to the land, and incidentally had some money in its pocket to buy their products, instead of ‘rights’ which could only be ‘cashed’ in grass for cows or wood to be cut. Hence the appearance of commercially-minded absolute monarchs who received such solid support from the towns.

The process which continued in England through the Tudors until the absolute monarchy had to be taught its real place in the capitalist scheme of things by Cromwell, was begun in France by Louis the Eleventh, and continued until certain inevitable and unwanted features of absolute monarchy had to be pruned by the French Revolution. When absolute monarchy had done its job, its disadvantages to the capitalists outweighed past advantages, and it was duly removed from the political scene in those countries where the capitalist producers were strong enough to do the governing jobs themselves. When, for various reasons, the operation could not be so neatly and efficiently performed in Germany, this has led to a prolonged inflammatory condition of the patient and consequent complications.

When they had settled accounts with the monarchy, the rising capitalist class had still to contend with the landed aristocracy, who were not as powerful in law as the old feudal barons, but were immensely influential socially. The men of the new wealth brought by the industrial revolution in England wanted to get rid of the Corn Laws which made food artificially dear for their workpeople, and which would have to be reflected in wages. They wanted the restraints imposed by the aristocrats abolished, and to do this they desired to bring in the lower middle class to help them.

Parliament, thus enriched, developed into a boxing ring for the rival groups. The landed classes, led by Lord Shaftesbury, brought in factory legislation, warmly supported by landlords who wished to get their own back on the factory owners. Disraeli’s whole policy centred round bringing more workers as Tory democracy ‘to dish the Whigs’. So long as the workers remained ardent Conservatives or passionate Liberals and did not create a class-party of their own, parliamentary democracy was regarded as the last word in perfect freedom for everyone.

It was not long before the landed proprietors joined the ranks of the industrial capitalists. Coal was found on their land. If the Old Man kept to the old ways, his sons had less scruples, and their titles were in demand for directorships and company prospectuses.

In this period of free competitive capitalism, parliament was needed to settle disputes between the great rival interests and their respective share in the state apparatus. The whole struggle between the trades catering mainly for the home market, which badly wanted protection from foreign competition, and the export and shipping trades, which wanted cheap raw material and investments abroad, had to be fought out in parliament – where else? Later when the great trade unions developed from the 1880s onwards, parliament was needed to ‘keep the ring’. The Taff Vale and Osborne Judgements with their reversal in parliament shows that the Liberal capitalists still wanted the support of the trade-union masses for their Free Trade policy. Later, when this was not so necessary, the Trades Disputes Act (1929), which prevented sympathetic strikes, and to an extent the political use of the trade-union funds, was voted by many of the Liberals who had voted on the workers’ side in 1913.

The change in the attitude to the trade-union question is symptomatic of the change that was taking place not only in England but all over capitalist Europe in the years that followed the war. The capitalists of the various nations were to a great extent united by finance-capital. The great banks and the great industries fused. The finance-capital which had united industry fused its interests with the state, and came to control that also.

In Germany, even before the war, the capitalists had been accustomed to use the state apparatus as their property. After the war and the revolution they quite openly regarded it as their pack-horse – unloading their debts on to the State Treasury by the simple threat to go bankrupt and throw their workers out of employment. The Hapag (shipping combine) got the money for their war losses in America from the German state. When they also received them from America they refused to return the money that had been advanced. When the Steel Trust was almost bankrupt and its stock was down to 30, the government bought shares (that were in the hands of the trust, not of the public) at 90. The bigger factories, particularly the cigarette companies, simply refused to pay taxes, and were repeatedly given amnesties.

At the present time the position that has been reached is that the important capitalists of any one of the big nations have become more or less united economically. They need only a governing body with power to settle their minor disputes, to bring rebels in their own groups into line (as the British government has used the tariff to bring some reorganisation into the steel industry), to keep down the workers (hence the Trades Disputes Act) and, most important of all, to defend their common interests against rival nations, as by Mr Runciman’s trade pacts. The Roosevelt New Deal is largely an experiment along these lines.

While capitalism continues these tendencies must develop. It becomes a condition for existence in the modern world of finance-capital that the state should be run on the same lines as a big business, with all the secrecy and unity of control that attends the directive operations of a great combine. Under these circumstances the urge to some form of dictatorship, open or veiled, becomes inevitable.

When people say that free Britons or republican Frenchmen would never stand a dictatorship, they overlook the fact that these same freemen and republicans may passionately demand exactly such a dictatorship to protect their interests in a world where that may have become necessary to their economic existence in a capitalist world. Something of the kind has already happened in that classic country of rugged individualism, the United States of America. Just as the masses fought for democracy when that was the political desire of the free competitive capitalism through which they earned their bread, so they may come to demand ‘monopoly politics’ when this becomes the condition of existence in a world of monopoly capitalism. Fascism is the political expression of this phase.

It is this fact that they do express a mass desire that is the new and characteristic feature of Fascism, and differentiates it from gangster tyranny and ordinary police reaction. Yet, at the same time, Fascism is the political expression of monopoly capitalism itself.

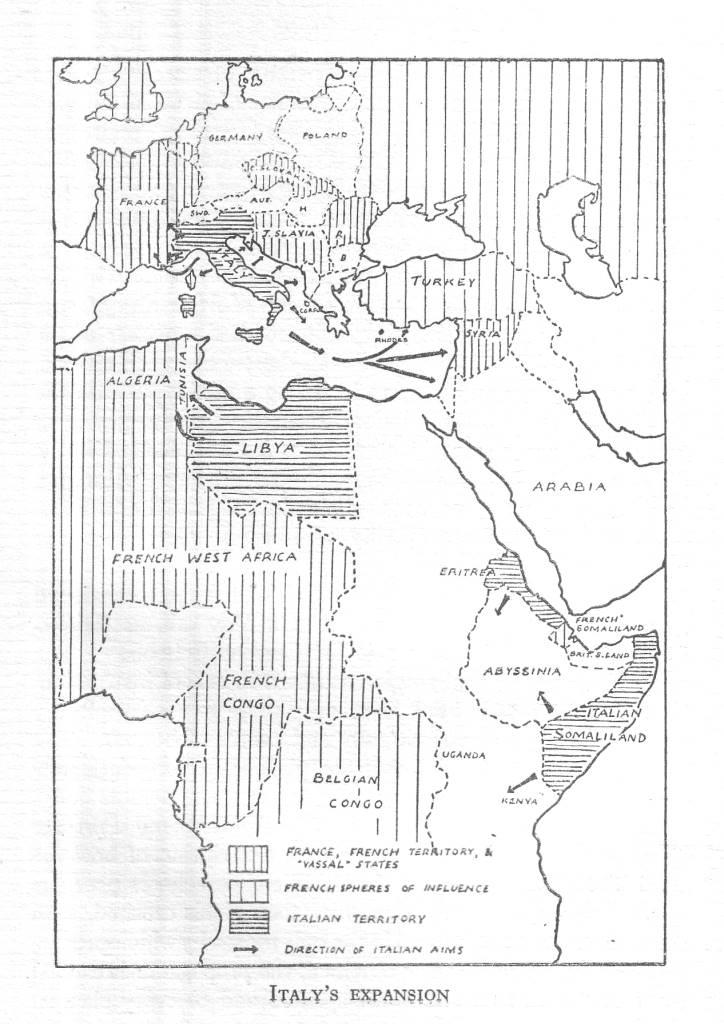

Capitalist Imperialism and Fascism: The same drive towards unified control is behind Fascist foreign policy. Aggressive, violent and militaristic imperialism is necessarily common to all Fascist movements. Mussolini declared that ‘imperialism is the eternal and immutable law of life itself’ – which ingeniously brings in the growth of the amoeba to excuse the appropriation of Fiume.

The plain facts of the situation as left by the war are now clear. The countries among the belligerents that have not yet gone Fascist are those who are satisfied with the booty they had got then and previously, and are more interested in developing and exploiting their territories than in extending them. The countries which have gone Fascist are those which lost territory then or which were very dissatisfied with their part in the share-out.

Forced back on the idea of war as the only way to alter that position, the Fascist countries militarise the entire nation. All national efforts are subordinated to preparation for war. Speaking at the close of the Italian Army manoeuvres on 24 August 1934, Mussolini said:

One must therefore be prepared not for a war of tomorrow, but for a war of today. We are becoming, and will become, always more prepared because we wish to be a military nation, and, not being fearful of words, militarist. This means that the entire life of the nation, political, economic and spiritual, must be directed towards those objects which constitute our military necessities.

In the same speech he claimed as a great achievement of Fascism that it had caused a radical change in the mentality of the people towards war: ‘If tomorrow the people were called upon they would reply as one man.’

In Germany, of course, imperialism and militarism are not inventions of the Fascist state. Prussia had risen to be a great power by its ruthless sacrifice of all considerations to military things. The impression had been stamped deep into the German consciousness. After the Revolution of 1918 the Reichswehr set itself to keep alive the military spirit, and to prepare a war of revenge. The special contribution of the Fascists was to unify the nation behind the policy of expansion, and to crush relentlessly and effectively all opposition to it. Nazi spokesmen declare that it is their highest aim to unite the German nation into one big fist. If Fascist countries can really produce this unity for war, then their creed becomes a formidable force which may compel great changes in the social organisation of the countries opposed to them.

The Psychological Preparation for War: The modern form of absolute state with its mass basis realises the power of propaganda. In Fascist Germany and Italy the great propaganda machinery of state and party is occupied in making the nation, more particularly the youth, interested in the idea of war. Pacifism is a crime. [4]

Internationalism and any creed tending to produce the international outlook are the objects of crusades of suppression – hence not only the campaign against the Jews, but the bitterness towards the much more powerful Roman Catholic Church, the suppression of Freemasonry and even of the Rotarians. The international solidarity of the workers is denounced as an invention of the Jews.

No one escapes the all-pervasive propaganda. Cigarette cards point the moral. The illustrated papers supply the interest. Military bands, frequent parades of marching troops, keep up the excitement. The new science of pictorial statistics is developed to a high point to show how Germany’s security is menaced and how strongly armed its neighbours. The effect is to create a desire for arms. Fighting in war is praised as the supreme virtue. The inevitability, necessity and greatness of war is regarded as the last word of wisdom.

Wisely, like all the best propagandists, they begin with the children. Hitler, in the German edition of Mein Kampf, says (p 715):

Then, in fact, beginning with the primer of the child, until the last newspaper, each theatre and each cinema, each news kiosk and each free hoarding must be put into the service of this one big mission, until the anxious prayer of the Philistine of today, ‘God make us free’, is changed in the brain of even the smallest boy into the prayer: ‘Almighty God, bless one day our arms. Be as just as you always were. Now judge if we are worthy of liberty. God bless our fight.’

It was in Thuringia that Herr Frick, in 1930, introduced prayers of hatred into the schools. On 9 May, as Reichsminister, he issued a new rule for German schools:

The military idea must find ample treatment in school instruction. The German people must learn once more to see in military service the highest patriotic duty and source of honour. The germ of the military idea must be planted in the youth now growing up.

Edgar Mowrer, in his brilliant book, Germany Puts the Clock Back, gives in his casual way a description of how the Nazi ideals had penetrated the middle-class schools previous to their gaining power. Now, with their rivals crushed, with the teachers anxious to excel in the only means by which promotion or even security can be obtained, the propaganda is carried through the whole educational system, and to every class in society.

In many universities, Departments of Military Science have been opened by the Nazi government in defiance of Paragraph 177 of the Treaty of Versailles. Political ‘education’ and military science take the place of science. The popular lectures deal with poison gas, the new methods of chemical warfare, military geography, electric transmission of military news, and all the exciting incidentals of a modern scientific war. German youth, which loves to break into song on any possible occasion, is supplied by the Nazi song-writers with songs of contempt for death and the dangers of the battlefield.

Psychologically more subtle is the attempt to condition the German people as a whole to war, to accustom them to the idea by homoeopathic doses. After all, even the German who is under 30 has had personal experience either of actual warfare, or the horrors that war can bring in its train – blockade, famine, inflation, social revolution. The German army suffered terribly in the trenches, and those experiences also are not forgotten. It needs very careful propaganda, helped of course as it has been by the Allies’ attitude in the first 12 years after the war, to overcome the natural desire for ‘No More War’ which has in England and France produced so deep and real a pacifism in the population.

A German film, Stosstrupp, 1917, has been produced with the help of the state. Part of it contains scenes actually taken in battle – the rest is the most realistic war stuff that has ever yet been shown. It was run through privately in London for a few English people. ‘Do the government intend this as pacifist propaganda?’, asked an Englishwoman, anxious to be reassured. A German not connected with the film pointed out that in Germany it was intended to have the contrary effect: ‘We made a great mistake with our talk of Britain’s contemptible little army. When our soldiers met it, the shock was felt through the country. This is to show our people the worst, and brace them to it.’

To the Englishman, there is something comic about an individual talking about his racial superiority, or the sacred egoism of the state. When it becomes part of the carefully taught philosophic basis of a great state, it seems somehow silly. Not that Englishmen haven’t those feelings about themselves. Their whole Empire has been built up on the firm conviction of the superiority of the Anglo-Saxon race. The Indian rages at the way he is treated almost instinctively as an inferior. The English express the same ideas in a different way.

Italian Fascism regards the sacred egoism of the nation as the main motive of all its actions. The Nazis claim that the interests of the nation, be it right or wrong, is the highest standard of action. Columns of good German argument fill the carefully controlled press to prove that ideas of justice, clemency and peace are useful only as instruments of propaganda in order to weaken an opponent. An analysis of Allied propaganda during the war, and the use of the Wilsonian Fourteen Points, supply any Nazi propagandist with all the illustrations that he needs to prove his contention.

The competition in bragging between Rome and Berlin, between Mussolini [5] and Hitler, has added to the amusement of the nations, and has led to a ‘prima-donna theory of the next war’, which it is assumed will come because of the rival claims of these two gentlemen to the world’s attention. But the throwing of bombs at each other depends on stronger forces than the energy with which they bestow verbal bouquets upon themselves.

In their psychological preparation for war, the Fascist leaders forget no detail, not even the necessary speeches in favour of the ideals of peace.

The psychological preparation for war brings the Fascists in a conflict of ideas with traditional Christianity. Chauvinism is always inclined to regard the nation as a more important entity than God. Religion is then regarded not as truth, but as a useful myth – as the leaders of the Action Française are fond of saying. The Pope could not ban the Fascists for such remarks, so he denounced the Action Française as public sinners and refused them Church wedding and burial.

Certain sections of Italian Fascists are filled with the desire to revive ‘pagan imperialism’ and tread in the steps of the pagan tradition of Ancient Rome. They glorify violence and barbarism in itself – war as value in itself, whether it be won or lost. ‘We despise those who, by such a small and insignificant war as the last one, are horrified and return to the rhetorics of humanity’, the former futurists, Evola, Marinette and their group, the Farinacci group, and politicians of his type, are fond of saying. But Evola recognises the value of the Church as myth. ‘I love Machiavelli too much’, he says, ‘not to give the advice to Fascism to make use of the Church whenever it can.’

The Nazis during their struggle for power could always count on the support of the higher Protestant clergy, and a good proportion of the younger pastors. They themselves have an appreciation of the value of organised religion as a social cement for their regime. Hitler, in 1934, declared that he wanted ‘to secure for the German people the great religious, moral and ethical value which exists in the two Christian confessions’. The Nazis also duly banned the Freemasons, and are driving back the people to Church by police methods. If it is doubtful whether a prisoner is a Communist or not, and is to be treated accordingly, the fact that he is not a member of the Church is regarded as proof of his Communism.

But while certain powerful and influential Nazis regard it as a matter of course that Fascism cannot exist ‘without the opium of religion’, they do not consider it necessary that this should be provided by the Christian religion. The situation is more complicated than the Italian one. Mystic sects and astrological movements have developed enormously in the new Germany.

The race religion which the Nazis are developing with such enthusiasm is obviously incompatible with traditional Christianity. Only a few Nazis, however, have gone so far as to break completely with the churches and try to found actual pagan sects to revive the pre-Christian heathenism of the old Teutons. They attempt to alter the essential teaching of Christianity by grafting on to the old tree strange new shoots. The ‘German Christians’ are indisputably German, but only by the queerest twisting of the ancient texts can they call themselves Christian.

There exist all shades of compromise, but these do not hide the fundamental fact that the Nazi outlook on life is completely different from the Christian. The Nazi faith is a half-mystical, half-materialistic theory which says that the value of a man is decided by his race or blood. It denies the equality of man before God. Its gospellers listens to the inspiration not of the Holy Ghost but of the ‘blood of the race’.

The new religion’s new prophet, Hitler, becomes a rival of the Founder of the old Religion, of Jesus of Nazareth whose own origin is so unfortunately Semitic, though certain Nazi theologians are kindly trying to do for Him the service of somehow proving that He was descended from Wotan and not from the Jewish King David.

The German Christians want to retain as much of Christianity as will stand the test of new Nazi values. Christianity is international – but: ‘A man’s nation comes first.’ ‘It is an impossible idea that one can acknowledge the Third Realm and yet obey God more than men.’ They advocate the abolition of the crucifix because it symbolises that Christ died like a slave. Germans, they declare, must feel themselves to be free men. Nazi and Christian values are incompatible. Of what use to a Storm Trooper are meekness and humility, charity and humanity? Strength, courage, manliness, ruthlessness, beauty and honour, these are the old Germanic virtues. Christ was an heroic Aryan figure, the victim of the Jews, his memory and tradition equally the victim of priests.

Herr Alfred Rosenberg, who is said to supervise the ‘entire intellectual and philosophical schooling of the German youth’, declares that ‘Nazism unconditionally subordinates the idea of neighbourly love to the idea of national honour’. Humility he describes as ‘an idea desired by the power-seeking church’, but unworthy of free Germans and heroes, who must oppose the pacifism which is inherent in the doctrine of Christianity.

The Technical Preparation of War: It is of course difficult to say anything really definite about the state of the technical preparation for war in Germany, despite the information which the French General Staff so obligingly allows to leak into the press of the world from time to time. [6]

Using only such facts as are reasonably free from propaganda or anti-German hysteria, it is now certain that since Germany discovered that the Allies have no means to stop their rearmament in defiance of treaties except blockade or preventive war, [7] for both or either of which to be effective the time has now gone by, the piling-up of arms has been unceasing. Germany has become an arsenal, not without the assistance of the private armament firms in the countries which are pledged to prevent that rearmament, and in return to disarm themselves.

Armaments and their subsidiaries form the most flourishing part of German industry. After one year of Nazi rule, Krupps could set aside £1,200,000 for completing and enlarging their works, which are giving 7000 workers employment for the present year, after having already taken on 5700 workers the year before. The number of employees at Krupps increased in 1933 from 46,000 to 60,000. The Chemical Trust is proposing to employ £450,000 for creating new work.

The value of the armament shares has been rising on the exchange, while the value of other shares has been going down. Armaments shares, in fact, rocketed by increases of from 30 per cent to 100 per cent in 1933, and the increase is being maintained.

The German chemical industry is still the best in the world. By its nature it is exceedingly difficult to control by any treaty, for there is no sharp line between production for peace and for war. For instance, a famous liqueur firm has had no difficulty in changing over to the production of more dangerous liquids suitable for sterner purposes than pleasantly aiding overloaded digestions. Poison gases do not need extensive and public grounds for their testing.

Tanks and big artillery which are forbidden to Germany are more difficult to manufacture, though there is always the possibility of test-types being made in pieces, which can be assembled very quickly. Certain parts of Krupps and other big armament firms are now kept closed to foreign visitors. Most of the biggest firms have foreign subsidiaries which can manufacture out of Germany to German requirements, without infringing treaties. They are particularly useful for tests and parts.

The import only of those commodities which are peculiarly useful in war have increased considerably at a time when the Nazi government is making frantic efforts to restrict imports because of the effect on the exchange. [8]

Cellulose wood cannot be needed for making paper, since the number of books and newspapers has decreased considerably, but it makes excellent raw material for explosives. The increase in iron-ore is worth noticing, in view of the fact that two years’ supply, about eight to nine million tons, have been stored since 1932.

The first year of the Third Reich raised the expenses for the army by 30 per cent to 650 million marks, for the navy by 50 million to 240 million, for the air 160 million as against 77 million. For air-defence 50 million as against 1.3 million were spent. These figures for air defence are especially interesting. No country has yet quite dared to bring home to the civil population what the next war is going to mean to them. Germany takes special pride now in emphasising this in every possible way. No new buildings must be erected without bomb-proof cellars.

In the more vulnerable towns already careful surveys have been made of the possible cellar accommodation and the state of its security against direct hits and gas. If war in the air comes soon, the German people will be best prepared both psychologically and physically for the early shocks. In the report to the League of Nations on air warfare, one of the leading experts said: ‘That nation stands the best chance in air warfare whose civil population has the strongest nerves.’ Goering’s entire mind and ambition are now concentrated on making the Germans a nation of airmen. Thousands of pilots are trained. Commercial flying, research into new fuels and the development of gliding planes are encouraged.

By Versailles the German Army is limited to 100,000 men. The republic began the moral breaking of the treaty by arming the police, militarising their drill and conditions and thus raised the effective army to 240,000. The Nazis added their Storm Troopers, about a million men whose training was superintended by Reichswehr officers, either serving or reserve.

The drive towards autarchy, for which so much else is sacrificed, only makes sense as a policy if it is regarded as part of the technical preparation for war. A leading member of the Economic Council of the NSDAP defined autarchy to the Allgemeene Handelsblaad (30 August 1933), an important Dutch newspaper, by saying:

Germany understands by autarchy its right to arrange its economic life in such a way that it builds a castle in which it can entrench itself in case it is besieged as a consequence of difficulties in the field of foreign exchange and trade, and in the last resort in case of war, without being in danger of dying from hunger and thirst.

The experiences of the war, when Germany found itself surrounded by enemies and its generals had forgotten, until too late, the necessity of providing for reserves of necessities of life other than immediate war material, have bitten deep into the German consciousness.

Hitler inherited a Germany which by intensification of agriculture had already gone far towards assuring itself a home-produced food supply. [9]

In 1925 Germany was still exporting [10] one-third of her bread-stuffs from abroad. Today she is practically self-sufficing. Now, though at a high price, Germany raises nearly all the meat her people can afford to buy. In potatoes, sugar, vegetables and dairy produce she can supply her own wants if the harvest is normal. But fats are definitely short. Nor are her supplies of eggs and fruit sufficient as yet. Most of her needs in these respects are supplied by the Balkan countries, which is why Germany’s political drive to the Balkans is so important for her. These sources of supply she must keep open at any cost for any future war.

Diplomatic Preparation for War: The Aims: The Nazi leaders are fond of saying that one must not be dogmatic about foreign policy. They have changed their views several times, and during the march to power, or for that matter even since they have attained it, there has been no real agreement among the leaders as to what they really want.

At first there was a general idea of collecting all the Western nations to fight Russia. This was the idea of the White Guardists who insinuated this policy into the Nazi mind. The Hugenberg Memorandum, during the Economic Conference in London in 1933, showed that this idea still had influential backing, and later on, in the attempts to come to terms with Japan, this rather vague notion is still kept alive as a possible basis for action.

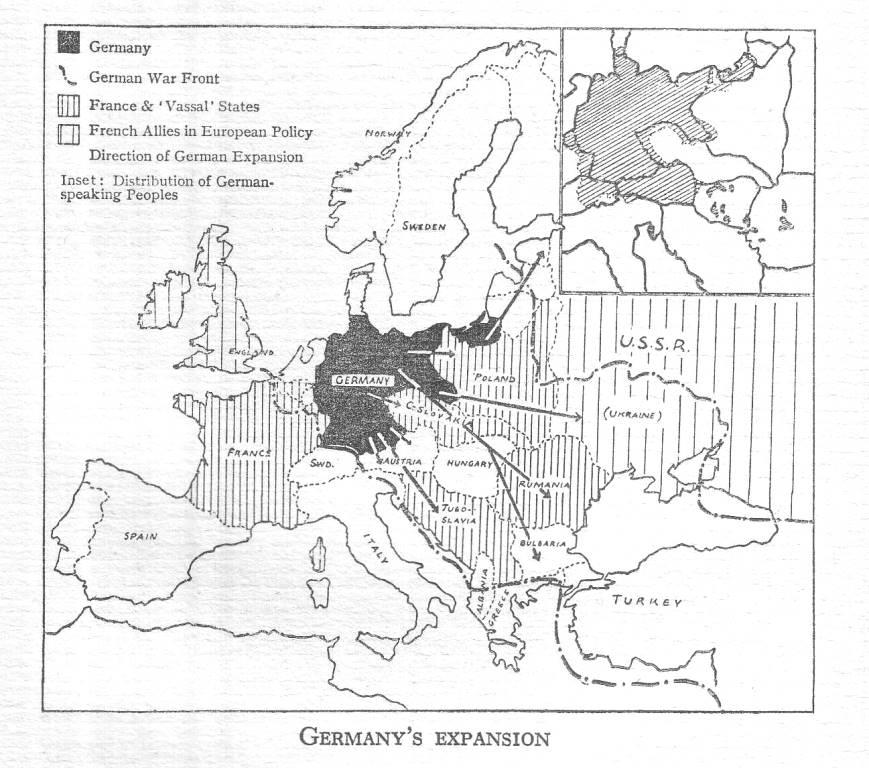

But to most of the Nazis, France remains the real enemy. Some of them would have been willing to unite with Russia in an attack on the Versailles powers. The Strassers, who led the North German Socialist wing, were mooting this notion in 1926-27. Hitler himself prefers an alliance with Italy and England against France. ‘France is and always will be the deadly enemy of Germany’, he says in Mein Kampf (p 699): ‘The extermination of France is a means of providing our people with the necessary room for expansion’, as ‘covering our rear for an extension of territory in Europe.’

In a broad general sense the chief aim of Nazi foreign policy is the establishment of a pan-German hegemony in Europe. Though 1 July has, with due ceremony, been made a colonial day, they are not specially concerned in winning back their colonies. In this the Nazi leaders are going back to the policy of Bismarck rather than that of William II. Bismarck refused to take colonies, because this would make Germany dependent on the goodwill of England, which can always cut off the Channel, and close Germany’s only route to Africa. In being so anxious to offer colonies to Germany, Lord Rothermere is showing himself a shrewd imperialist, for such a gift would, in fact, become a hostage to England’s goodwill.

Now that they are in power there are two chief aims in Nazi foreign policy. First, they are firmly determined to unite all Germans in Europe. Gottfried Feder, in the Nazi programme, says: ‘All of German blood, whether living under French, Danish, Polish, Czech or Italian sovereignty, shall be united in a German Reich.’ He adds:

We claim all Germans in Sudeten Germany (Czechoslovakia), Alsace Lorraine, and the states which succeeded to the old Austria as well as the League Colony of Austria. This demand, however, expressly excludes any tendency towards imperialism. It is the simple and natural demand which any strong nationality puts forward as its natural requirement.

Some of the Nazis include even Holland, Switzerland, Flanders and parts of Sweden among the ‘German countries’.

The second aim is the expansion of the East, for so long a deep, strong undercurrent in German foreign politics. ‘To give the German peasant freedom in the East is the basis for the entire regeneration of our nation’, says Rosenberg. The German Fascists want the south-east – the Balkans – as their customers and allies. They want the Ukraine and the Baltic States for the settlement of peasants.

Their first difficulty, however, is to pull Germany out of the complete isolation in which it stood during the first months of the Hitler regime, when it managed to offend and frighten more people than even Wilhelm Hohenzollern was able to rouse against him. Only after this isolation is broken will the way be clear to work on the lines of Hitler’s declaration: ‘So in the future, it is not by the grace of nationality that we shall gain the land which is the life-blood of our people; but by the might of a victorious sword.’ (Mein Kampf, p 741)

Diplomatic Preparation for War: The Method: For the breaking down of isolation, and uniting the irredentist Germans with the Motherland once more, Nazi Germany is first concentrating on two countries with an overwhelming German population, the Saar and Austria. The Nazis proceeded by intimidation and terror to prepare for the plebiscite of January 1935. They boycotted those who did not join the German Front, the Nazi organisation. On marches through the towns and villages, houses that did not display the Nazi flag were ostentatiously noted – ‘for future use’.

According to the report of Mr Knox, the League of Nations Commissioner, in January 1934, the Nazi Party had already usurped the rights and powers of a governing authority:

It has organised a disguised administration of the territory at the side of the legal government; issued manifestoes direct to the Saar communal authorities; issued certificates declaring parcels to be duty free, and added its own visas to the regular police visas on identification cards.

The League of Nations can, under the Treaty of Versailles, withhold the territory from Germany, even if the Germans won the plebiscite. Then Germany would have a strong moral case in any dispute with France. The Saar is so valuable for its coal-mines, and its heavy industries that it would be a useful acquisition to either side in case of war.

In Austria, the Nazis quite openly subsidised and organised civil war. They have attempted to ruin the most important industry little Austria has left – the tourist traffic – by demanding the equivalent of 1000 marks (£70) from every German who goes to Austria. They organised Austrian emigrants into military formations, sent them back to carry on subversive propaganda, and organised rescues if they were put into prison.

The radio propaganda was incessant in spite of strong representations from the other powers. Terrorism grew in insolence and violence, until the individual acts of terror ended in an insurrection conducted with German rifles and machine-guns, their opponents being equipped with Italian weapons.

After the murder of Dollfuss the victors of Versailles were united in a wave of moral indignation. The more spectacular forms of bullying stopped for the time, but it is impossible not to be struck by the similarity between the Hitler Putsch of 1923 and the Austrian Putsch of July 1934.

Mussolini outmanoeuvred the Nazis under the pretext of ‘defending Austria’s independence as a sovereign state’. But the close collaboration, not to say dependence, of the new Austrian Chancellor and Prince Starhemberg on Italian help and advice gave the Nazis the chance of recovering a certain amount of the lost prestige by emphasising this humiliation before Austria’s hereditary enemy.

For the moment Italian Fascism had in this the powerful help of the Roman Catholic Church, which desires to build up a clerical Fascist state of its own according to the principles of social justice as expounded in the Encyclica Quadragesimo Anno, and interpreted by Prince Starhemberg and Major Fey.

Owing to the similarity in speech and tradition and the feeling of a common nationhood, besides the enormous economic advantage that some form of link-up with Germany would give to bankrupt Austria, it is obvious that in the long run Nazi Germany will gain a very strong influence also in Austria’s official policy. The Nazi leaders are particularly anxious to get Austria, firstly because it will heighten their prestige considerably in carrying out their policy of unifying all Germans, but, even more important, because it is necessary for their Balkan policy. At the height of its power, the old Imperial Germany united the Balkans under its rule from 1915 to 1918. This is one of the lines of German imperialist expansion, and Nazi Germany wants to regain the old position.

France is the chief opponent in Europe of German imperialist policy. Therefore it is necessary for the Nazis to break the French system of allies. The mention of this would have caused laughter in the first months of Fascist rule – that the unpopular Nazis should be able to break that ring of steel and gold which the French had hammered together after the war, and which had been the despair of every leading German statesman in the years that followed.

Diplomatic Preparation for War: The Successes: By their first success, the treaty with Poland, they secured what had seemed impossible – an understanding with Poland which the Germans would themselves accept. For nine years a bitter trade war had waged between the two countries. German exports to Poland had decreased by 88 per cent from 1925 to 1933, a period when the general fall in exports had been 47 per cent. Germany’s share of the Polish trade was reduced in this period from 38 per cent to 18 per cent, and Poland’s share in German trade sank from 4.5 per cent to 1.2 per cent.

The Hugenberg papers, in revenge for the confiscation of Junker property in the former German territories, assailed the Poles daily with all the abuse they could think of. The Polish replies were not exactly models of courtesy. Thus the feeling between the two peoples was just about as bad as it could be without any actual declaration of hostilities.

But when France did not back Poland’s request for a preventive war as soon as the Nazis came to power, and when it became clear that France could also not prevent German disarmament, Poland realised that it would probably be wiser to come to some sort of an understanding with Germany. It was an auspicious moment. The Nazis were prepared to sacrifice anything to lessen their own isolation, and to begin the breaking of the French ring. A treaty was signed with Poland for which, had it been signed before they came to power, they would have demanded and probably effected the assassination of the statesman who was responsible, and made the treaty the object of a raging campaign of vilification throughout Germany.

But all the Nazi weight was now thrown on the other side. Unfriendly propaganda was suppressed in both countries. Customs war and trade restrictions ended. Agreements were concluded between the Polish and German iron industry and shipping lines. The Ten-Year Pact of Non-Aggression (26 January 1934) has developed into a condition of mutual understanding. Foreign countries were accustomed to shrug their shoulders at Germany’s clumsy prewar diplomacy. But it is not possible to withhold from the Nazis credit for the Polish achievement, and for the friction between France and Poland which ensued, of which the immediate cause was the sending of Polish workers out of France and the endangering of French capitalist interests in Poland by the arrest of their representatives.

This treaty, as a glance at a map will show, freed the Nazis’ hands in the East. All German statesmen and soldiers had learned from the lessons of 1914 the dangers of war on two fronts. The Völkische Beobachter at once insinuated that the pact meant Polish neutrality in case of war between Germany and France.

For, as Hitler had said in Mein Kampf (p 749): ‘An alliance whose aim does not include the intention of war is worthless nonsense.’ But in addition the Polish pact was of the utmost importance for clearing the way to the East, for the Nazis’ pet plan of settling their peasants in the Ukraine. And if it be objected that this would mean, even if successful, bits of Germany separated from the Motherland by other countries, a glance at an historical map of the Germany of Frederick the Great will show that this is how Prussia started on her career of greatness. Once having got the scattered bits, it becomes the aim of policy to connect them together. Towards such a policy, at the present day, a beginning could only be made with the consent of Poland.

In the other countries of the French ring, where there are considerable numbers of Germans, the Nazis have worked on the tried principles of the Comintern by setting up, fostering, when necessary subsidising, a Nazi Party in them. It is, of course, absurd to assume that all the Fascist parties which grew up after Hitler came to power are instruments of Nazi foreign policy, or to go as far as some writers have done, and regard their existence as a sign that the country concerned is to be annexed into the German system. It is obvious that in France, for example, it is not love of Hitler, but fear of him that has encouraged Fascism. But in Czechoslovakia, to organise the three million Germans who feel that they have not had a fair deal from the triumphant Czechs, paralyses Czechoslovakian policy. Any overt act by Czechoslovakia against Germany would mean a revolt in the German regions which are contiguous to German territory. Thus an important section of the French ring is put out of effective action.

In Rumania, with its tradition of friendship to France, which has cost much good French money to maintain, the Nazis have helped the anti-Semitic Fascist Iron Guards to change the course of Rumanian foreign policy. Since the quarrel with Mussolini over Austria, the way has opened for flattering offers of friendship and economic concessions to be made to Italy’s nearest and bitterest enemy, Yugoslavia. In March 1934, several leading Yugoslav politicians found opportunities of stating that there seemed to be no reason for conflict between the two countries and that collaboration might be possible.

In Bulgaria they have suffered a reverse. Whether it can be retrieved remains to be seen. King Boris visited Berlin and was received with every flattering attention. After conversations with the Nazi government he returned to Bulgaria a convinced pro-German. But so important a break in the French ring could not be tolerated, and Russia, now a friend of France, had her own reasons for assisting in blocking Germany here. French gold bought sufficiently influential generals to ensure a Putsch which, while it proclaimed its determination to suppress Communism with all severity in Bulgaria, at the same time put good relations with the USSR among the statement of its aims. King Boris realised that he must be complacent if he hoped to keep his throne, and his recognition of the inevitable – at least for the moment – was suitably greeted with rejoicings by his loyal subjects.

The money of French agents has arrested German success in the Balkans because Germany is short of foreign currency, but the situation is not likely to rest there. The Nazis’ most capable agents are at work assuring the Balkan statesmen that they want a ‘participation of Germany in the policy of the Danube territory’, but that this does not mean ‘that Germany comes as a military conqueror to the Balkans’ (Völkische Beobachter, 20 March 1934). ‘Germany’, says the same authority, ‘can give to these countries the economic and social possibilities which they need as a backbone to solve the existing difficulties.’ As a matter of fact the Nazis can offer substantial advantages to these Balkan peoples. Her great industrial areas are the natural markets for the agrarian products of Eastern Europe, and could then, themselves, take Germany’s machine products. South-east Europe, threatened by the cheap food from America, was practically ruined by the autarchic policy of Germany. Now that the cheap American products are cut off from Germany also, the opening of the German markets more freely to the Balkans would mean a great revival of trade between the two, and would go far towards the solution of the East European agrarian crisis. For a solution of her potato shortage in the winter of 1934, Germany made arrangements for large imports from Yugoslavia.

The Nazis, however, are well aware that this policy can only be carried out if England can be induced to look upon the developments with at least benevolence. In fact, they want to revive the plan of the great German economist, F List (1846), to rule the Balkans together with England. Britain is interested in South-east Europe as being on the way to India, and the Nazis have no desire to interfere with British interests in that direction. They would be prepared to further them in whatever way might be required.

Of course, all this is suitably disguised in passionate speeches for popular consumption. The Völkische Beobachter may be trusted to supply the appropriate comments. ‘To France’, it says, ‘which wants to subject the peoples of Europe, is opposed Germany, which stands for the right of all nations to live. Dictatorship and freedom, violence and peace are opposed in France and Germany.’ The sentiments are unexceptionable – only it is a little difficult to know which is which.

1. Ernst Henri, Hitler Over Europe (London, 1934).

2. RP Dutt, Fascism and Social Revolution (London, 1934).

3. The Lavoro Fascista comments upon the German Leader Law: ‘German National Socialism has delivered over the German worker bound hand and foot to capitalism.’ It describes it as ‘smacking of the Middle Ages’ and as ‘bringing to nought everything achieved by the workers through the struggles of the last hundred years’.

4. Von Papen said (14 May 1933) that pacifists ‘could not understand the ancient German aversion from the death in the bed. Mothers must exhaust themselves in order to give life to children. Fathers must fight in the battlefield in order to secure the future of their sons.’ Röhm (Völkische Beobachter, 8 December 1933) defines ‘pacifism is, according to the view of the soldier, cowardice on principle. Cowardice is no philosophy but a defect in character.’

5. On 16 October 1933, the Popolo d'Italia writes: ‘In some months or years the great breakdown of civilisation will be a fact. Then mankind will see at the sky of Rome the beloved, the powerful and rescuing forms of the new civilisation which will be Fascist, Corporative and Italian. Mankind shall hear in the impenetrable silence of the world, the word of Mussolini like a Gospel which announces a new life.’

6. See Albert Schreiner and Dorothy Woodman, Germany Rearms: An Exposure Of Germany’s War Plans (London, 1934).

7. See Ellen Wilkinson and Edward Conze, Why War: A Handbook For Those Who Will Take Part In the Second World War (London, 1934).

8. Imports of Germany:

Production figure 1932 1933 Increase % Iron 170,000 430,000 250 Iron ores 3,450,000 4,576,000 75 Nickel 2,300 4,400 90 Nickel ore 17,000 34,000 100 Cellulose wood 1,200,000 2,500,000 100 Tungsten ores 1,700 3,700 100

9. Agricultural statistics:

Production figure 1924-25 1932 Wheat 27,000 50,000 Rye 65,000 83,000 Barley (1926) 25,000 32,000 Oats 53,000 66,000 Potatoes 355,000 470,000

Livestock slaughter (million) 1924 1931 Cattle 2.9 3.4 Calves 3.8 4.1 Sheep 1.8 1.6 Pigs 10.3 20.5

10. The word ‘importing’ is surely meant here – MIA.