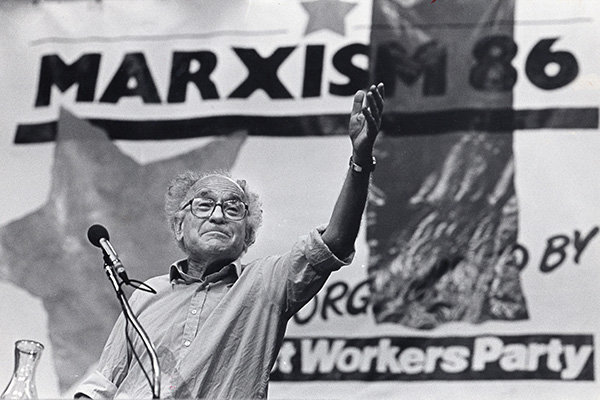

Tony Cliff speaking at Marxism 1986 (Pic: John Sturrock)

MIA > Archive > Cliff > Obituaries etc.

From Socialist Worker, No. 1692, 14 April 2000.

Copied with thanks from the Socialist Worker Website.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

|

Tony Cliff, the founder of what became the Socialist Workers Party, died on 9 April 2000. Twenty years on, we republished the obituary we printed at the time. |

Tony Cliff speaking at Marxism 1986 (Pic: John Sturrock) |

Tony Cliff, who died on Sunday, was an inspiration to successive generations of socialists. The inspiration came from his incredible dynamism, his hatred of every form of oppression, and the clarity of his ideas. He was born in Palestine in 1917, the son of Jewish settlers from the old Russian Empire.

He got involved in politics at the age of 14 or 15, just as the Nazis were rising to power in Germany. He was forced to confront the horror of what Nazism meant-many of his own relatives in Europe were to perish in the death camps. He could see that capitalists had sponsored Hitler’s rise to power and became a revolutionary socialist.

But Cliff also found that the main organisations that called themselves socialist had abandoned the fight for a better world. The German Social Democrat Party at first told its members not to fight Hitler because he was keeping to the German constitution. The German Communist Party, obeying the orders of Stalin in Russia, insisted that Hitler was not a real danger-until it was too late.

Cliff began to see that the only way to fight for a better world was to follow the call of the exiled leader of the Russian Revolution, Leon Trotsky, and to oppose both capitalism and the bureaucracy that ruled Russia. He also found that fighting oppression meant challenging the ideas of the Zionist settlers in Palestine, then a British colony.

The Zionist trade union, the Histadrut, followed a policy of trying to exclude Arabs from jobs. Left wing Zionists claimed the answer to the oppression of Jews in Europe was to unite with the British Empire in oppressing the local Arab population.

One of Cliff’s first political memories was of being beaten up at a supposedly left wing meeting because he called for Jewish workers to unite with Arab workers.

Cliff’s opposition to colonialism led the British authorities in Palestine to imprison him during the Second World War.

Cliff moved to Britain after the war, determined to fight for socialism at the centre of an empire that then ran a third of the world. The Labour government of the time responded in a liberal manner which would have brought joy to the heart of Ann Widdecombe or Jack Straw, by deporting him to Ireland! It was only when the Tories returned to office in the early 1950s that he was allowed to rejoin his family in London.

In these years he made astounding contributions to Marxist theory. More than 99 percent of opponents of capitalism in the West and the Third World at the time regarded Russia and the other countries of the Eastern Bloc as socialist.

Even the small groups of followers of Trotsky, who was assassinated by Stalin’s agent in 1940, still held to his view that these were “workers’ states” of a “degenerated” sort. Cliff set out to defend this view himself-and found it fitted neither with the facts about life in Russia nor with the view of the state to be found in the writings of Marx, Engels and Lenin.

Not afraid to face up to reality, he came to the conclusion that a completely new view of Russia was needed if socialists were to struggle consistently against exploitation and oppression.

He provided this in his pathbreaking book State Capitalism in Russia, written when he was only 30. In later writings he extended his analysis to the countries of Eastern Europe, to China and to many of the new regimes that called themselves “socialist” in the Third World.

But Cliff did not merely expose these regimes as non-socialist. He also challenged the idea that they were like the society portrayed in George Orwell’s novel 1984, under the control of a regime so powerful that no opposition could ever succeed.

Cliff showed that the so-called “Communist” countries were a form of capitalism, with the state as the only boss. Like every other form of capitalism, it was giving rise to an ever bigger working class with the potential to shake society apart. This happened in Hungary in 1956, and then in Czechoslovakia, Poland and eventually Russia itself.

His slogan, “Neither Washington nor Moscow”, provided socialists with a way of resisting pressures from the rival imperialisms during the miserable decades of the Cold War.

It also prevented them suffering terrible disillusion when the Berlin Wall came down and the USSR eventually collapsed. Cliff also produced an important analysis of Western capitalism alongside his account of Russian state capitalism.

Socialists were surprised when capitalism did not experience more slumps in the 1950s and 1960s.

|

Not afraid to face up to reality, he came to the conclusion that a completely new view of Russia was needed |

Cliff recognised that the system had stabilised, but that this was due to the ultimate horror of piling up weapons of mass destruction. This, however, could not prevent the eventual return of devastating economic crises – and he was proved right. Economic crisis returned in 1974–6, 1980–1, and in the 1990s.

During the 1950s illusions in both Russia and Western capitalism were at a peak. Cliff had to reconcile himself to finding a very small audience for his ideas and to building a socialist organisation of only a few dozen members.

Nonetheless, Cliff travelled from one end of the country to another, speaking to meetings – a pattern he kept to right up to the last months of his life.

Hearing him speak to a dozen-strong meeting in Watford in 1961 was a revelation to a young socialist like me. Here was someone able to make sense of the system on both sides in the Cold War and to explain how to fight it.

The year 1968 was a turning point, with the student and anti-war movement in the US, the general strike in France and the events in Czechoslovakia. As thousands of people began to question the system, Cliff began to find a large audience. His organisation, the International Socialists, grew rapidly among students.

Then, in 1969, a Labour government tried to introduce anti-union laws. Cliff had already produced a pamphlet for shop stewards on the threat of wage controls which sold 20,000 copies.

He followed it up with a book on productivity deals and inspired many of the new student socialists to take the arguments over the union laws into the factories, mines and docks. He also ensured there was a clear socialist opposition to the wave of racism which followed Enoch Powell’s repeated attacks on black and Asian people.

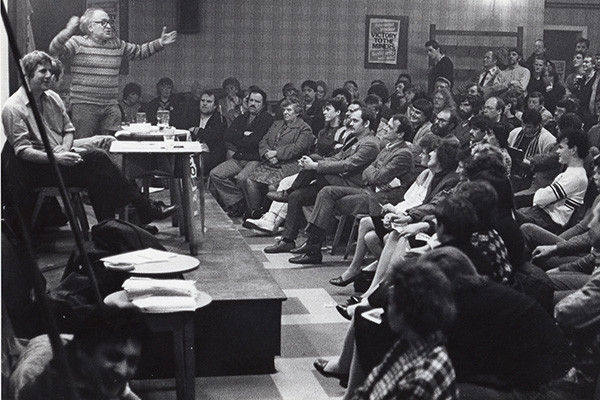

Tony Cliff speaking at a meeting in Barnsley during the miners’ strike in 1985 (Pic: John Sturrock) |

The International Socialists grew in the years of strikes and protests which culminated in the fall of Heath’s Tory government in 1974. Cliff won the respect of thousands of activists as he displayed his amazing ability to give concrete expression to abstract ideas, using a repertoire of jokes, stories and metaphors.

But after 1974 the union leaders worked with the new Labour government and the employers to bring the ferment in the workplaces to an end. The employers took advantage of the political confusion amongst militants and launched a counter-attack on workers’ organisations. In 1979 the election of Margaret Thatcher crowned efforts that had begun with the connivance of Labour ministers four years earlier.

Once again Cliff insisted on looking reality in the face. He was among the first on the left in Britain to recognise that the years of rising struggle were over, arguing that a new period of “downturn” had begun.

This prepared the Socialist Workers Party (the new name for the International Socialists) for the hard years of the 1980s which saw the defeat of steel workers, miners, and print workers at Wapping. Cliff certainly did not ease up on his activity in these years yet he still found time to complete biographies of Lenin and Trotsky.

Cliff rejected the idea, common on the left in the early 1980s, that joining the Labour Party and electing left wingers could lead to quick victories.

He said there had to be a revival of struggle. He could see signs of it in the last decade of his life with the growth of a new political bitterness, not only in Britain but internationally-in Italy, Germany and, above all, France.

Once again there was a new audience for socialist ideas, and once again Cliff threw himself into addressing it. He insisted again and again that if we do not succeed in building mass revolutionary socialist organisation then the bitterness created by the crisis of the system could lead to the growth of fascist forces as in the 1930s.

Only three weeks before his death he inspired an SWP new members’ school when he spoke of the challenge facing socialist organisations in the 21st century.

But the inspiration was not only in Britain. Socialist organisations based on the ideas developed by Tony Cliff now exist in most advanced capitalist countries, and in places like South Korea, Zimbabwe, Turkey and Poland. In all of them people will be shocked and saddened by the news of Cliff’s death.

In all of them we will sorely miss his brain and his determination. But in all of them we will also be inspired by his 70 years of struggle to redouble our own fight for a better world.

Last updated on 19 April 2020