MIA > Archive > P. Foot > Why you should be a socialist

|

‘There’s a world called Arsy Versy, whose ways are very queer, |

|

The thirty years dream is over. Since the end of the Second World War, people have imagined that things will get better. Now they are not getting better. They are getting worse.

In the thirty years there has been progress, fantastic progress. In every area of human activity, in industry and science; in medicine and agriculture; in building technology and transport wonders can be performed which would have read like science fiction thirty years ago.

For most of those thirty years it looked as though the dark days of the 1930s had disappeared for ever.

It looked, for the first time, as though scientific and industrial progress would bring security and an ever-improving standard of life for the working people.

Now, very suddenly, all that is vanishing.

Suddenly, in factories and offices and council estates all over the country, there is insecurity and gloom. Wages, which have gradually increased over those thirty years, are not increasing any more.

Foods which working people have come to accept as staple diets can no longer be afforded. In 1976, the British people ate 20 per cent less meat, five per cent less eggs and even drank less milk than in the previous year. The Sunday joint, and the eggs and bacon breakfast, relatively easy to afford for most of the last thirty years, are now luxuries.

For the first time in all those thirty years, the living standards of working people went down. The fall seems a small one, just one or two per cent, but in most families it meant more than that. It meant no more evenings out; no more holidays, no more conversations on the telephone, no more of the small but vital pleasures which kept many a household sane and cheerful.

At the same time the public services which working people had come to take for granted started to disintegrate. Minor treatment at a hospital, which would have taken an hour or two, often involves a long day’s waiting. School meals and milk cost money. Fares of every kind are rocketing. Buses are less frequent and more expensive. Train journeys are being priced right out of the reach of many workers’ families. In 1976, on the route from London to Glasgow, passenger traffic fell by a staggering 30 per cent.

None of this will get better. The government’s own plans until 1980 prove it. By 1980, these plans will double council house rents, double the price of all basic foods, and even double the cost of electricity, which has already been doubled over the past two years. Even on the existing plans for the next three years, classrooms and hospital wards will become dirtier and more overcrowded. Transport will become more expensive and less frequent. The great hope of the 1950s and 1960s that scientific and industrial progress would bring a better life for the people who do the work is shattered.

At the same time, twelve million really poor people in Britain are growing desperate. A survey in November 1975 found that these people manage to find an average £1.84 per head for food every week: and that’s before the 1976 rises in food prices, which have been the highest since figures were recorded. In July 1976, Linda Deighton, a 23-year-old woman in Sheffield was getting £14 a week for herself and her baby. Every day she faced the problem: should she eat a meal, or give it to the baby. The baby won most days. If it wasn’t for a kindly neighbour, Linda would have starved by now.

Most of the really poor are old people. They are suffering horribly from the rise in the price of food. But they have an even more terrifying problem: how to keep warm. In the mild winter of 1975-6, some 100,000 old people died because they could not afford to keep warm enough.

In Dundee, in March 1976, George Stevenson, aged 71, who had been a shipyard riveter all his life, was burnt to death when his attic caught fire from the candle which provided his only light and heat.

Part of the dream of the last thirty years was that the ‘welfare state’ would provide more and more handsomely for the poor in our society: for the old and the sick and the disabled and the one parent families.

That dream is turning into a nightmare.

In the last two years, five million more people have fallen below the government’s poverty line. The Child Poverty Action Group predict that the number will increase by as much again this year.

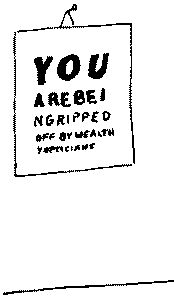

‘We’re living beyond our means!’ is the parrot cry of politicians, economic experts and television pundits. For years, they whine, we’ve been gorging ourselves on clean schools and regular transport. For years we’ve employed too much staff in hospitals and day nurseries. Now we can’t afford to improve our standard of life.

But many of these things have been afforded, even when we were producing much less.

In 1948, when the national income was half what is now, people who wear spectacles (about half the population) and need false teeth (again about half) could get them free. Now both are so expensive as to be beyond the reach of hundreds of thousands of people who need them. In some cases dental care on the National Health Service is more expensive than private care. Medicine and drug prescriptions, free in 1948, cost 20p each now, and will rise again. School meals, free in 1948, will cost 25p each next year. In 1948 there were day nursery places for 71,045 children, paid for by the State. Now there are 25,700 and the numbers are going down. If we could ‘afford’ to provide all these things free then, why can’t we afford them now?

All around us is the evidence of what we could afford if only we produced what we need and shared it out fairly.

The year in which there are more hungry people in Britain than any other time for twenty years is the year of the biggest British beef mountain. By April 1976, a thousand tons of beef a week – that’s enough to provide three million joints – was sold into cold storage, where it will lose its nutritional value. One month later, the first British butter mountain was created; and, a month later, the first cheese mountain. The prices of all these basic foods kept going up as the government slashed food subsidies.

As subsidies were slashed, so food prices went up. The acreage of potatoes on which prices are guaranteed fell from 580,000 acres in 1971 to 500,000 in 1976 – all because of cuts in subsidy. A bad harvest and scarcity drove potatoes up in price from 4p to 12p, at which ridiculous level the price has stuck – ever since.

As prices went up in the shops, so the farmers sold more and more food into British and European stores, where the farmers were offered a handsome price. There is plenty of beef, butter; cheese; plenty of milk and eggs. There are plenty of hungry people. But somehow the hungry and the food do not meet.

In the same year that more pensioners were dying of cold than ever since the war, the government announced the closure of twenty-three power stations – plus another eighteen by March 1977.

These closures will wipe out 3,419 megawatts of electricity, enough to provide heat and light for every old age pensioner in the country. The old people are dying of cold, and the power stations are being closed down.

There are more homeless in Britain today than there were a hundred years ago when Frederick Engels wrote his terrible indictment of homelessness, The Condition of the English Working Class. But the 1971 Census showed 675,880 empty houses in Britain, enough for all the homeless. 300,000 of these houses were the second, third, fourth and even fifth houses of rich people and rich companies.

Everywhere you look there are idle resources: half-empty trains, half-empty hotels, machinery in factories standing idle.

Here is a table which shows the drop in the production of some of our basic industries since the peak year of 1973 (and even in 1973 many industries were not working to full capacity).

|

1970 = 100 |

|

September 1973 |

|

September 1976 |

|

All goods and services |

110.8 |

102.3 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All manufacturing |

108.3 |

103.3 |

||

|

Metal manufacture (mostly steel) |

103 |

85 |

||

|

Engineering |

108 |

98 |

Yes, in steel, engineering (and textiles) we were producing less in 1976 than we were producing in 1970! Just think what that means in terms of wasted machinery.

But then there’s the biggest waste of all: unemployment. There are one and a quarter million people on the register, and at least three quarters of a million not registered who are prepared to work, but can’t because there isn’t a job to go to.

These include 20,000 men and women who have been fully trained as teachers and can’t find jobs in the overcrowded, overstressed schools.

And in the overcrowded, overstressed hospitals, nurses who have finished their training are being dismissed and forced onto the dole. In 1976 for the first time in living memory, there were more trained nurses on the dole than vacancies for nurses.

If those one and a half million were working, they’d be producing six billion pounds worth more goods and services: that’s more than is spent on all health, or all education, or all housing!

We can afford to feed the hungry, provide shelter for the homeless, and warmth for the old. We can afford to improve the standard of living of everyone in our society. It’s not that we’re living beyond our means. The problem is that we’re not making full use of our means.

The factories are there, the industrial technology is there, the scientific know-how is there, the skills of the workers are there – and the needs and wants of people are plain for all to see. The problem is that they can’t be matched up. We can produce what people need – but we don’t.

The same lunacy goes on all over the world.

After thirty years of unprecedented scientific progress, five hundred million people, an eighth of all the people in the world, can hardly move their bodies because of hunger. Half of these people are children under five. Half the world’s population, that’s two thousand million people, are not getting enough to eat.

There’s plenty of food in the world.

This year there has been a record wheat harvest – 391 million tons; that’s two hundredweight for every human being – more than enough to keep everyone well-fed.

There could be much more. Edgar Owens, of the United States Agency for International Development, told a conference in November 1974:

‘If the arable land of our planet was cultivated as efficiently as farms in Holland, the planet would feed sixty-seven billion people, seventeen times as many people as are now alive.’

The Food and Agricultural Organisation, in a statement in 1976, said:

‘There would be no difficulty whatever with the existing resources and knowledge in doubling world food production.’

Forty years ago, the American writer John Steinbeck wrote a wonderful novel The Grapes of Wrath. It was about the unemployed and starving workers of California during the great slump. Through the thoughts of one of the unemployed who was driven to picking fruit to stay alive, John Steinbeck summed up the frustrations of a lost generation.

‘Men have transformed the world with their knowledge. The short lean wheat has been made big and productive. Little sour apples have grown large and sweet, and that old grape that grew among the trees and fed the birds has mothered a thousand varieties, red and black, green and pale pink, purple and yellow; and each variety with its own flavour.

‘The men who work in the experimental farms have made new fruits; nectarines and forty kinds of plums, walnuts with paper shells and always they work, selecting, grafting, changing, driving themselves, driving the earth to produce.

‘But men who graft the trees and make the seeds fertile and big can find no way to make the hungry eat their produce.

‘A million people hungry, needing the fruit – and kerosene spread over the golden mountains. And the smell of rot fills the country.

‘The people come with nets to fish for potatoes in the river, and the guards hold them back. They come in rattling cars to get the dumped oranges but the kerosene is sprayed. And they stand still and watch the potatoes flow by, listen to the screaming pigs being killed in a ditch and covered with quicklime, watch the mountains of oranges slop down to a putrefying ooze.

‘And in the eyes of the people there is a failure and in the eyes of the hungry there is a growing wrath.’

That was an eloquent expression of fury at the dark age known as ‘The Thirties’. Now, in the ’70s, the same failure is just as evident, just as horrible.

And now, in the ’70s, as the thirty years’ dream comes to an end, there is a growing wrath, not just in the eyes of the hungry, but in the eyes of hundreds of thousands of working people.

They want to know why, after all that hope and progress, they have to cut their living standards to the bone. They want to know why the wealth which they produce is being poured into the gutter or the cold store, why they cannot produce the things they need – and what they can do about it.

Last updated on 16.1.2005