William Z. Foster

The Great Steel Strike and Its Lessons

PITTSBURGH DISTRICT—THE RAILROAD MEN—CORRUPT NEWSPAPERS —CHICAGO DISTRICT—FEDERAL TROOPS AT GARY—YOUNGSTOWN DISTRICT—THE AMALGAMATED ASSOCIATION—CLEVELAND—THE ROD AND WIRE MILL STRIKE—THE BETHLEHEM PLANTS—BUFFALO AND LACKAWANNA—WHEELING AND STEUBENVILLE—PUEBLO— JOHNSTOWN—MOB RULE—THE END OF THE STRIKE.

Although the Steel strike was national in scope and manifested the same general, basic tendencies everywhere, nevertheless it differed enough from place to place to render necessary some indication of particular events in the various districts in order to convey a clear conception of the movement as a whole. It is the purpose of this chapter to point out a few of these salient features in the several localities and to draw some lessons therefrom.

In the immediate Pittsburgh district, due to the extreme difficulties under which the organizing work was carried on and the strike inaugurated, the shut-down was not so thorough as elsewhere. Considerable numbers of men, notably in the skilled trades, remained at work, and the mills limped along, at least pretending to operate. This was exceedingly bad, Pittsburgh being the strategic centre of the strike, as it is of the industry, and the companies were making tremendous capital of the fact that the mills there were still producing steel. Accordingly, the National Committee left no stone unturned to complete the tie-up, already 75 per cent. effective. But under the circumstances, with meetings banned and picketing prohibited, it was out of the question to reach directly the men who had stayed at work. The key to the situation was in the hands of the railroad men.

Operating between the various steel plants and connecting them up with the main lines, there are several switching roads, such as the Union Railroad and the McKeesport and Monongahela Connecting Lines. They are the nerve centers of the local steel industry. If they could be struck the mills would have to come to a standstill. The National Committee immediately delegated organizers to investigate the situation. These reported that the body of the men in the operating departments were organized; that they had no contracts with the steel companies, and that they were ready for action, but awaiting co-operation from their respective national headquarters.

Consequently, the National Committee arranged a conference in Washington with responsible representatives of the Brotherhoods and laid the situation before them. In reply they stated that their policy was strictly to observe their contracts wherever they had such, and that their men would be forbidden to do work around the mills not done by them prior to the strike. It was up to the men on the non-contract roads and yards to decide for themselves about joining the strike. We informed them then that the situation was such, with the men scattered through many locals, that merely leaving it up to them was insufficient; it would be impossible for them to act together without direct aid and encouragement from their higher officials. We made the specific request that each of the organizations send a man into Pittsburgh to take a strike vote of the men in question, who are all employees of the steel companies. They took the matter under advisement; but nothing came of it, although long afterwards, when the opportune moment had passed, organizer J. M. Patterson of the Railway Carmen (also of the Trainmen) was authorized to take a strike vote. Thus was lost the chance to close down these strategic switching lines and with them, in all likelihood, several big mills in the most vital district in the entire steel industry.

Throughout the strike zone general disappointment was expressed by the steel workers at the apparent lack of sympathy with their cause shown by the officials of the Brotherhoods. The steel workers, bitterly oppressed for a generation and fighting desperately towards the light in the face of unheard-of opposition, turned instinctively for aid to their closely related, powerfully organized fellow workers, the railroad men. And the latter could easily have lent them effective, if not decisive assistance without violating a contract or in any way endangering their standing. It was not to be expected that the trunk line men, working as they were under government agreements, would refuse to haul the scab steel; but there were many other ways, perfectly legitimate under current trade-union practice and ethics, in which help could have been given; yet it was not. From Youngstown and elsewhere the railroad men who did go on strike in the mill yards complained with bitterness that they were neglected and denied strike benefits, and that the rule that no road man should do work around the mills not customary before the strike was flagrantly violated. Usually the rank and file were strongly disposed to assist the hard-pressed steel workers, and they could have everywhere wonderfully stiffened the strike, but the necessary encouragement and cooperation from the several headquarters was lacking. Truth demands that these unpleasant things be set down. Labor can learn and progress only through a frank acknowledgment and discussion of its weaknesses, mistakes and failures.

In addition to all their other handicaps the Pittsburgh district strikers had to contend with a particularly treacherous local press. Everywhere our daily papers are newspapers only by courtesy of a misapplied term. They are sailing under false colors. Pretending to be purveyors of unbiased accounts of current happenings, they are in reality merely propaganda organs, twisting, garbling and suppressing facts and information in the manner best calculated to further the interests of the employing class. The whole newsgathering and distributing system is a gigantic mental prostitution. Consequently, considering the issues involved, it was not surprising to see the big daily papers take such a decided stand against the steel workers. Everywhere in steel districts the papers were bad enough, but those in the Pittsburgh district outstripped all the rest. They gave themselves over body and soul to the service of the Steel Trust.

From the first these Pittsburgh papers were violently antagonistic to the steel workers. Every sophistry uttered by Mr. Gary to the effect that the strike was an effort to establish the “closed shop,” a bid for power, or an attempt at revolution, the papers echoed and re-echoed ad nauseum. They played up the race issue, virtually advising the Americans to stand together against the foreigners who were about to overwhelm them. They painted the interests of the country as being synonymous with those of the steel companies and tried to make Americanism identical with scabbery. For them no further proof of one’s patriotism was needed than to go back to the mills. Every clubbing of strikers was the heroic work of the law-abiding against reckless mobs. Strike “riots” were manufactured out of whole cloth. For instance, when the senators investigating the strike were visiting the Homestead mills, a couple of strike-breakers quarreling with each other, several blocks away, fired a shot. An hour later screaming headlines told the startled populace of Pittsburgh that “STRIKERS SHOOT AT SENATORS” and “MOB ATTACKS SENATE COMMITTEE.” Even the stand-pat senators had to protest that this was going it too strong.

In revenge for an alleged dynamiting in Donora, Pa., the authorities swooped down upon the union headquarters, arrested 101 strikers present, including organizer Walter Hodges, and charged them with the crime. Since there was not a shred of evidence against the accused, they were all eventually discharged. Then the Donora Herald, which forever yelped that the organizers advocated violence, had this to say:

One of the reasons we have sedition preached in America is because we have grand juries like that at Washington (Pa.) this week which ignored the dynamiting cases. Possibly the biggest mistake of all was made in not using rifles at the time instead of turning the guilty parties over to the very sensitive mercies of the grand jury.

But the journalistic strike-breaking master-stroke was an organized effort to stampede the men back to work by minimizing the strike’s effectiveness. First the papers declared that only a few thousands of Pittsburgh’s steel workers went out. Then they followed this for weeks with stories of thousands of men flocking back to the mills. Full page advertisements begged the men to go back; while flaming headlines told us that “MEN GO BACK TO MILLS,” “STEEL STRIKE WANING,” “MILLS OPERATING STRONGER,” “MORE MEN GO BACK TO WORK,” etc. It became a joke, but the patient Pittsburgh people couldn’t see it. Said Wm. Hard in the Metropolitan for February, 1920:

“Mr. Foster,” I said, “I am going to be perfectly frank with you. I know your strike’s a fizzle of course, but I know more. I not only take pains to read the telegraphic dispatches of the news from the managers of the steel mills, but I keep the clippings. I have the history of your strike in cold print. Hardly anybody struck anyhow, in most places, except some foreigners; and then they began at once to go back in thousands and thousands and new thousands every day for months. If you claim there were 300,000 strikers, I don’t care. I’ve counted up the fellows that went back to work, and I’ve totalled them up day by day. They’re a little over 4,800,000. So you’re pretty far behind.”

But despite everything—the suppression of free speech and free assembly, Cossack terrorism, official tyranny, prostitution of the courts, attacks from the lying press, and all the rest of it—the steel workers in the immediate Pittsburgh district (comprising the towns along the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers from Apollo to Monessen) made a splendid fight. The very pressure seemed to hold them the better together. Their ranks were never really broken, the strike being weakened only by a long, costly wearing-away process. The stampede back to work, so eagerly striven for by the employers, did not materialize. In the beginning of the strike the Pittsburgh district was the weakest point in the battle line; at the end it was one of the very strongest.

The Chicago district struck very well, but it weakened earlier than others. This was because the employers scored a break-through at Indiana Harbor and Gary, particularly the latter place, which shattered the whole line.

Gary, the great western stronghold of the United States Steel Corporation, was the storm center of the Chicago district at all times. Hardly had the organization campaign begun in 1918, when the Gary Tribune bitterly assailed the unions, accusing them of advocating evasion of the draft, discouragement of liberty bond sales, and general opposition to the war program. These lies were run in a full page editorial in English, and repeated in a special eight page supplement containing sixteen languages, a half page to each. Many thousands of copies were scattered broadcast. Other attacks in a similar vein followed. It was a foul blast straight from the maw of the Steel Trust. Incidentally it created a situation which shows how the steel men control public opinion.

The new unions immediately boycotted the Tribune. Result: the Gary Post, somewhat friendly inclined, doubled its circulation at once. The Post then became more friendly; whereupon, it is alleged, a leading banker called the editor to his office and told him that if he did not take a stand against the unions his credit would be stopped, which would have meant suspension within the week. That very day the Post joined the Tribune’s campaign of abuse. Apparently the Post’s youthful editor had learned a new wrinkle in journalism.

The Steel Trust did all it could to hold Gary from unionizing; but when the strike came the walkout was estimated to be 97 per cent. At first everything went peacefully, but the Steel Corporation was watching for an opportunity to get its strategic Gary mills into operation. The occasion presented itself on October 4, when strikers coming from a meeting fell foul of some homeward bound scabs. Local labor men declare the resultant scrimmage “did not make as much disturbance as ordinarily would occur in a saloon when two or three men were fighting.” It was a trivial incident—a matter for the police. Only one man was injured, and he very slightly. But the inspired press yelled red murder and pictured the hospitals as full of wounded. The militia were ordered in. The unions offered to furnish 700 ex-service men to enforce law and order; but this was rejected. Later the militia were transferred to Indiana Harbor; on October 6, a provisional regiment of regular troops, under command of General Leonard Wood, came to Gary from nearby Fort Sheridan, and martial law was at once proclaimed. The Steel Corporation now had the situation in hand; and the Gary strike was doomed.

Grave charges were voiced against the misuse made of the Federal troops in Gary. John Fitzpatrick writes me as follows, basing his statements upon reliable witnesses:

Now we have military control, the city of Gary being placed under martial law. The strike leaders and pickets were arrested by the soldiers and put to work splitting wood and sweeping the streets. This was most humiliating, because the camp was across the street from the city hall and in the most frequented part of the city.

When street-sweeping here did not break their spirits, these men were taken to the back streets, where they had their homes and where their own and the neighbor’s children watched them through the windows.

The so-called foreigners have great respect for law and authority, especially military authority, which plays such a big part in their native environments. The U. S. Steel Corporation did not fail to take advantage of this. In the first place they gave out the impression that the letters “U. S.” in the corporation’s name indicated that it was owned by the U. S. Government, and that the Government soldiers being in town meant that any one interfering with the steel company’s affairs would be deported or sent to Fort Leavenworth.

Then a mill superintendent would take a squad of soldiers and go to the home of a striker. The soldiers would be lined up in front of the house; the superintendent would go in. He would tell John that he came to give him his last chance to return to work, saying that if he refused he would either go to jail or be deported. Then he would take John to the window and show him the row of soldiers. John would look at the wife and kids and make up his mind that his first duty was to them; that was what the strike was for anyway. So he would put on his coat and go back to the mills. Then the superintendent would go to the next house and repeat the performance.

Such tactics, coupled with spectacular midnight raids to “unearth” the widely advertised “red” plotters,—conveniently ignored until the strike,—the suppression of meetings, limitations on picketing, and the hundred forms of studied intimidation practiced by the soldiery, in a few weeks broke the backbone of the strike. And while the regular troops operated so successfully and systematically against the workers in Gary, the militia did almost as well in Indiana Harbor, where the strike also cracked.

The great reactionary interests which backed General Wood for the Republican presidential nomination, including the Steel Trust, are giving him boundless credit for breaking the steel strike in Gary. Consequently there are many workers who believe the whole affair was staged to further his political fortunes. If not, how did it happen that the militia, who could have handled the situation easily, were sent out of Gary to make room for his regulars? And why was it that before there was a sign of trouble General Wood had formed his provisional regiment, shipped it from Fort Dodge to Fort Sheridan, and made other active preparations to invade Gary? And then, how did it come that he took charge of the situation in person, when at best it was only a colonel’s job? In fact, how about the whole wretched business? Was it merely a political stunt to give General Wood the publicity that came to him for it?

The collapse at Gary and Indiana Harbor affected adversely South Chicago and almost the whole Chicago district. Worse still, it weakened the morale everywhere; and thus undermined, the strike rapidly disintegrated. By the middle of November, district secretary De Young reported that all the mills in the district, except those in Joliet and Waukegan, were working crews from 50 to 85 per cent. of normal, although, due to green hands and demoralized working forces, production averaged considerably lower. And the situation gradually grew worse. Joliet and Waukegan, however, held fast to the end, making a fight comparable with that of the men in Peoria and Hammond, who had gone out several weeks before September 22. It was at the latter place that police and company guards brutally shot down and killed four strikers on September 9.

In the immediate Youngstown district the strike was highly effective, hardly a ton of steel being produced anywhere for several weeks. This was due largely to the walkout of the railroad men employed in the mill yards, who acted on their own volition. Many of these belonged to the Brotherhoods, and others to the Switchmen’s Union, while some were unorganized; but all struck together. Then they held joint mass meetings, got an agreement from the A. F. of L. unions that they would be protected and represented in any settlement made, and stuck loyally to the finish. They were a strong mainstay of the strike.

The weakening of the strike began about November 15. In a number of plants, notably those of the Trumbull Steel Company and the Sharon Steel Hoop Company, the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers had agreements covering the skilled steel making trades, but when the laborers struck these skilled men had to quit also. The break in the district came when the Amalgamated Association virtually forced the laborers back to work in these shops in order to get them in operation. This action its officials justified by the following clause in their agreements:

It was agreed that when a scale or scales are signed in general or local conferences, said scales or contracts shall be considered inviolate for that scale year, and should the employees of any departments (who do not come under the above named scales or contracts) become members of the Amalgamated Association during the said scale year, the Amalgamated Association may present a scale of wages covering said employees, but in case men and management cannot come to an agreement on said scale, same shall be held over until the next general or local conference, and all men shall continue work until the expiration of the scale year.

Relying upon their rights under this clause, the companies naturally refused to give the laborers any consideration whatever until the end of the scale year. This meant that the latter were told to work and wait until the following June, when their grievances would be taken up. The result was disastrous; the laborers generally lost faith in the Amalgamated Association, feeling that they had been sacrificed for the skilled workers. They began to flock back to work in all the plants. Then men in other trades took the position that it was foolish for them to fight on, seeing that the Amalgamated Association was forcing its men back into the mills. A general movement millward set in. By December 10 the strike was in bad shape. In passing it may be noted that in Pittsburgh and other places where it had contracts, the Amalgamated Association took the same action, with the same general results, although not so extensive and harmful as in the Youngstown district. In Cleveland the charters were taken from local unions that refused to abide by this clause.

The other trades affiliated with the National Committee protested against the enforcement of the clause. They declared it to be invalid, because it violated trade-union principles and fundamental human rights. Seeing that no consideration was given the laborers under the agreement, their right to strike should have been preserved inviolate. It verged upon peonage to tie them up with an agreement that gave them no protection yet deprived them of the right to defend themselves. These trades freely predicted that to enforce the clause would break the strike in the Youngstown district, as it was altogether out of the question to ask men who had been on strike two months (especially men inexperienced in unionism) to resume work upon such conditions. But all arguments were vain; the Amalgamated Association officials were as adamant. They held their agreements with the employers to be sacred and to rank above any covenants they had entered into with the co-operating trades. They would enforce them to the letter—the interests of the laborers, the mechanical trades, and even the strike itself, to the contrary notwithstanding. Being a federated body, the National Committee had to bow to this decision and stand by, helpless, while its effects worked havoc with the strike.

Into Youngstown, in common with all the other districts, armies of scabs were poured. It was the policy of the United States Steel Corporation to operate, or at least to pretend to operate its mills, regardless of cost. So all the “independents” had to do likewise. Word came to the National Committee of several companies which, rather than try to run with the high-priced, worthless strike-breakers, would have been glad either to settle with the unions or to close their plants. But they were afraid to do either; Gary had said “Operate,” and it was a case of do that or risk going out of business.

The demand for scabs was tremendous. Probably half the strike-breaking agencies in the country were engaged in recruiting them. Thousands of negroes were brought from the South, and thousands of guttersnipe whites from the big northern cities. But worst of all were the skilled steel workers from outlying sections. There were many of such men who went on strike in their own home towns, sneaked away to other steel centres and worked there until the strike was over. Then they would return to their old jobs with cock-and-bull stories (for the workers only) of having worked in other industries, thus seeking to escape the dreaded odium of being known as scabs. These contemptible cowards, being competent workers, wrought incalculable injury to the strike everywhere, especially in the Youngstown district.

The Youngstown authorities, to begin with, were reasonably fair towards the strikers; but as the strike wore on and the steel companies and business men became desperate at the determined resistance of the workers, they began to apply “Pennsylvania tactics.” In Youngstown and East Youngstown, Mayors Craver and McVey prohibited meetings, “the object of which is discussion of matters pertaining to prolonging the strike.”(1) On November 22, district secretary McCadden, and organizers John Klinsky and Frank Kurowsky were arrested in East Youngstown, charged with criminal syndicalism and held for $3,000 bonds each. Later a whole local union, No. 104 Amalgamated Association, was arrested in the same town for holding a business meeting. “Citizens’ committees” were formed, and open threats made to tar and feather all the organizers and drive them out of town. But the steel companies were unable to inflame public opinion sufficiently for them to venture this outrage.

Afterward the organizers were discharged; and in releasing the men arrested for holding a business meeting, Judge David G. Jenkins said:

I regard the ordinance (E. Youngstown anti-free assembly) as a form of hysteria which has been sweeping the country, whereby well-meaning people, in the guise of patriots, have sought to preserve America even though going to the extent of denying the fundamental principles upon which Americanism is based, and free assemblage is one of those fundamentals.

In the principal outlying towns of the Youngstown district, namely Butler, Farrell, Sharon, Newcastle and Canton, the strikers were given the worst of it. The first four being Pennsylvania towns, no specific description of them is necessary. Suffice it to say that typical Cossack conditions prevailed. In Canton it was not much better. The companies turned loose many vicious gunmen on the strikers. The mayor was removed from office and his place given to a company man; and a sweeping injunction was issued against the strikers, denying them many fundamental rights.(2) The district, nevertheless, held remarkably well.

Cleveland from the first to the last was one of the strong points in the battle line. On September 22 the men struck almost 100 per cent. in all the big plants, and until the very end preserved a wonderful solidarity. Under the excellent control of the organizers working with Secretary Raisse there was at no time a serious break in the ranks, and when the strike was called off on January 8, at least 50 per cent. of the men were still out, with production not over 30 per cent. of normal. Thousands of the men refused to go back to the mills at all, leaving them badly crippled.

The backbone of the Cleveland strike was the enormous mills of the American Steel and Wire Co. This calls attention to the fact that, as a whole, the employees of this subsidiary of the U. S. Steel Corporation made incomparably a better fight than did the workers in any other considerable branch of the steel industry. Long after the strike had been cracked in all other sections of the industry, the rod and wire mill men of Cleveland, Donora, Braddock, Rankin, Joliet and Waukegan stood practically solid. Even as late as December 27, only twelve days before the end, the companies were forced to the expedient of assembling a rump meeting in Cleveland of delegates from many centres, for the purpose of calling off the strike. But the men voted unanimously for continuation under the leadership of the National Committee. When the strike was finally ended, however, they accepted the decision with good grace, because they were penetrated with the general strike idea and realized the folly of trying alone to whip the united steel companies.

The remarkable fight of the rod and wire mill men was due in large measure to the peculiar circumstances surrounding their organization. These are highly important and require explanation: The regular system used by the National Committee resulted usually in organization from the bottom upward; that is, in response to the general appeals made to the men in the great mass meetings, ordinarily the first to join the unions were the unskilled, who are the workers with the least to lose, the most to gain, and consequently those most likely to take a chance. Gradually, as the confidence of the men developed, the movement would extend on up through the plants until it included the highest skilled men. Given time and a reasonable opportunity, it was an infallible system. It was far superior to the old trade-union plan of working solely from the top down, because the latter always stopped before it got to the main body of the men, the unskilled workers.

The “bottom upward” system was used with the rod and wire mills, the same as with all others. But while it was operating the skilled men who had been attracted to the movement in Joliet, Donora and Cleveland started a “top downward” movement of their own. They sent committees to all the large rod and wire mills in the country, appealing to the skilled men to organize. These committeemen, actual workers and acquainted with all the old timers in the business, could do more real organizing in a day with their tradesmen than regular organizers could in a month. Hardly would they go into a locality, no matter how difficult, than they would at once inspire that confidence in the movement which is so indispensable, and which takes organizers so long to develop. The result was a “top downward” movement working simultaneously with the “bottom upward” drive, which produced a high degree of organization for the rod and wire mill men.

A great weakness of the strike was the failure of many skilled workers to participate therein. This tended directly to aid the employers, and also to discourage the unskilled workers, who looked for their more expert brothers to take the lead in the strike as well as in the regular shop experiences. The explanation has been offered that this aloofness was because the skilled men are “unorganizable.” But this is a dream. In the mills controlled by it, the Amalgamated Association (which is really a skilled workers’ union) has thousands of them in its ranks, most of whom earn higher wages than employees of similar classes in the Trust mills. If the proper means to organize them could have been applied, the skilled workers would have been the leaders in the late strike, instead of generally the scabs. The same thing done in the rod and wire mills should have been done in all the important sections of the industry, blast furnaces, open hearths, sheet, tin, rail, plate, tube mills, etc. Committees of well-known skilled workers in these departments should have been sent forth everywhere to start movements from the top to meet the great surge coming up from the bottom. Had this been done, then Gary with all his millions could not have broken the strike. The tie-up would have been so complete and enduring that a settlement would have been compulsory.

But it was impossible; the chronic lack of resources prevented it. With the pitifully inadequate funds and men at its disposal, all the National Committee could do was to go ahead with its general campaign, leaving the detail and special work undone. It is certainly to be hoped that in the next big drive this committee system will be extensively followed. It is the solution of the skilled worker problem, and when applied intelligently in connection with the fundamental “bottom upward” movement, it must result in the organization of the industry.

In the Bethlehem Steel Company’s plants the strike was not very effective. This was due principally to the failure of previous strikes and to general lack of organization. In Reading and in Lebanon there had been strikes on for many weeks before the big walkout. The workers’ ranks there were already broken. In Sparrows’ Point likewise several departments had been on strike since May 3. Not more than 500 men, principally laborers and tin mill workers, responded to the general strike call; but they made a hard fight of it. In Steelton the men had been very strongly organized during the war; but the error was made of putting all the trades into one federal union. Then when the craft unions insisted later that their men be turned over to them, the resultant resistance of the members, and especially of the paid officers, virtually destroyed the organization. When the strike came only a small percentage struck, nor did they stick long.

Speaking of the strike in the main plant at Bethlehem, Secretary Hendricks says:

The strike was called September 29, and about 75 per cent. of the men responded. These were largely American workers. The Machinists, which comprise about 40 per cent. of the total workers, were the craft most involved. In the mill and blast furnace departments, the response was among the rollers, heaters, and highly skilled men generally, which led to the complete shut-down of these departments. The molders practically shut the foundries down. Electrical workers, steamfitters, millwrights, and general repairmen responded well. The patternmakers did not go out.

The first break came a week later. It was charged largely to the steam engineers, who heeded the strike-breaking advice of their international officials and returned to work. Another factor was the failure of support from the railroad men on the inter-plant system. Had these two bodies of men been held in line by their officers, the Bethlehem strike would have been a success.

In the Bethlehem situation too much reliance was placed in the skilled trades; more attention should have been given to the organization of the real fighting force, the unskilled workers. Another mistake was to have allowed the strikes to take place in Reading, Lebanon and Sparrows’ Point. Even a tyro could see that they had no hope of success. Those men could easily have been held in line until the big strike, to the enormous strengthening of the latter. The National Committee had little to do with the Bethlehem situation before the strike, the movement developing to a great extent independently.

Nowhere in the strike zone was there a more bitter fight than in the Buffalo district, which was directed by organizers Thompson and Streifler. All the important plants were affected, but the storm centered around the Lackawanna Steel Company. This concern left nothing undone to defeat its workers. For eight months it had prevented any meetings from being held in Lackawanna, and then, when the workers broke through this obstruction and crowded into the unions, it discharged hundreds of them. This put the iron into the workers’ hearts, and they made an heroic struggle. So firm were their ranks that when the general strike was called off on January 8, they voted to continue the fight in Lackawanna. But this was soon seen to be hopeless.

Much company violence was used in the Lackawanna strike. The New York State Constabulary and the company guards, of a cut with their odious Pennsylvania brethren, slugged, shot and jailed men and women in real Steel Trust style. Many strikers were injured, and two killed outright. One of these, Joseph Mazurek, a native-born American, was freshly back from the fighting in France. Lackawanna was just a little bit of an industrial hell.(3)

As a strike measure the Lackawanna Steel Company evicted many strikers from the company houses. In Braddock, Rankin, Homestead, Butler, Wierton, Natrona, Bethlehem and many other places, the companies put similar pressure upon their men, either evicting them or foreclosing the mortgages on their half-paid-for houses. Threats of such action drove thousands back to work, it being peculiarly terrifying to workers to find themselves deprived of their homes in winter time. Where evictions actually occurred the victims usually had to leave town or find crowded quarters with other strikers. The much-lauded housing schemes of the steel companies are merely one of a whole arsenal of weapons to crush the independence of their workers. No employer should be permitted to own or control the houses in which his men live.

The Wheeling district is noted as strong union country. The “independent” mills therein had provided the main strength of the Amalgamated Association for several years prior to this movement; but the Trust mills were still unorganized. Under the guidance of National Committee local secretary J. M. Peters, however, these men, in the mills of Wheeling, Bellaire, Benwood and Martin’s Ferry, were brought into the unions. On September 22 they struck 100 per cent., completely closing all the plants. They held practically solid until the first week in December, when they broke heavily.

The immediate cause of this break merits explanation. The National Committee, at the outset of the strike, organized a publicity department, headed by Mr. Edwin Newdick, formerly of the National War Labor Board. In addition to getting out strike stories for the press, many of which were written by the well-known novelist, Mary Heaton Vorse, this department assembled and issued in printed bulletin form statistical information relative to the progress and effectiveness of the strike. The steel companies, through spies in the unions, newspapers, etc., disputed this information, telling the strikers that they were being victimized as the mills in all districts except their own were in full operation, and advising them to send out committees to investigate the situation.

It was a seductive argument and many were deceived by it. Consequently, quite generally, such committees (usually financed and chaperoned by the local Chambers of Commerce) went forth from various localities. Of course, they returned the sort of reports the companies wished. Much harm was done thereby. The Steubenville district suffered from the lying statement of such a committee, the strikers having made a winning fight up till the time it was made public, the middle of November. But nowhere was the effect so serious as in the Wheeling district.

The Wheeling committee was headed by one Robert Edwards, widely known for years as an extreme radical. It visited many points in the steel industry, taking its figures on steel production and strike conditions from employers’ sources, and completely ignoring national and local strike officials everywhere. The ensuing report pictured the steel industry as virtually normal. Although he had been recently expelled from the Amalgamated Association Edwards still had great influence with the men, and his report broke their ranks. In future general strikes drastic disciplinary measures should be taken to forestall the activities of such committees.

Of the 6500 men employed by the Colorado Fuel and Iron Co. in its Pueblo mills, 95 per cent. walked out on September 22. When the strike was called off three and one-half months later not over 1500 of these had returned to their jobs. Production was below 20 per cent. of normal. Locally the tie-up was so effective that on January 9, at the biggest labor meeting in Pueblo’s history, National Committee local secretary W. H. Young and the other organizers had to beg the men for hours to go back to work. These officials knew that the great struggle had been decided in the enormous steel centers of the East (Pueblo being credited with producing only two per cent. of the nation’s steel) and that it would be madness for them to try to win the fight alone.

The heart of the Pueblo strike was opposition to the Rockefeller Industrial Plan, in force in the mills. This worthless, tyrannical arrangement the men could not tolerate and were determined to contest to the end. Realizing the minor importance of the Pueblo mills in the national strike, the men offered at the outset to waive all their demands pending its settlement, provided the company would agree to meet with their representatives later to take up these matters. But this was flatly refused; it was either accept the Rockefeller Plan or fight, even though 98 per cent. of the men had voted to abolish it.

Shortly after this incident John D. Rockefeller, Jr., gained much favorable comment and pleasing publicity by his glowing speech about industrial democracy and the right of collective bargaining, delivered at the National Industrial Conference at Washington, D. C. He was hailed as one of the country’s progressive employers. But when the striking Pueblo workers wired him, requesting that he grant them these rights, he referred them to Mr. Welborn, President of the C. F. and I. Company, well knowing that this gentleman would deny their plea.

The strike was markedly peaceful throughout, no one being hurt and hardly any one arrested. But on December 28, the state militia were suddenly brought in, ostensibly because of an attack supposed to have been made two days previously upon Mr. F. E. Parks, manager of the Minnequa works. The public never learned the details of this mysterious affair which served so well to bring in the troops. Nor was the “culprit” ever located, although large rewards were offered for his capture.

The Johnstown strike was so complete that for eight weeks the great Cambria Steel Co., despite strenuous efforts, could not put a single department of its enormous mills into operation. Every trick was used to break the strike. The Back-To-Work organization(4) labored ceaselessly, holding meetings and writing and telephoning the workers to coax or intimidate them back to their jobs. Droves of scabs were brought in from outside points. But to no effect; the workers held fast. Then the company embarked upon the usual Pennsylvania policy of terrorism.

I, personally, was the first to feel its weight. I was billed to speak in Johnstown on November 7. Upon alighting from the train I was met by two newspaper men who advised me to quit the town at once, stating that the business men and company officials had held a meeting the night before and organized a “Citizens’ Committee,” which was to break the strike by applying “Duquesne tactics.” Beginning with myself, all the organizers were to be driven from the city. Disregarding this warning, I started for the Labor Temple; but was again warned by the newspapermen, and finally stopped on the street by city detectives, who told me that it would be at the risk of my life to take a step nearer the meeting place. I demanded protection, but it was not forthcoming. I was told to leave.

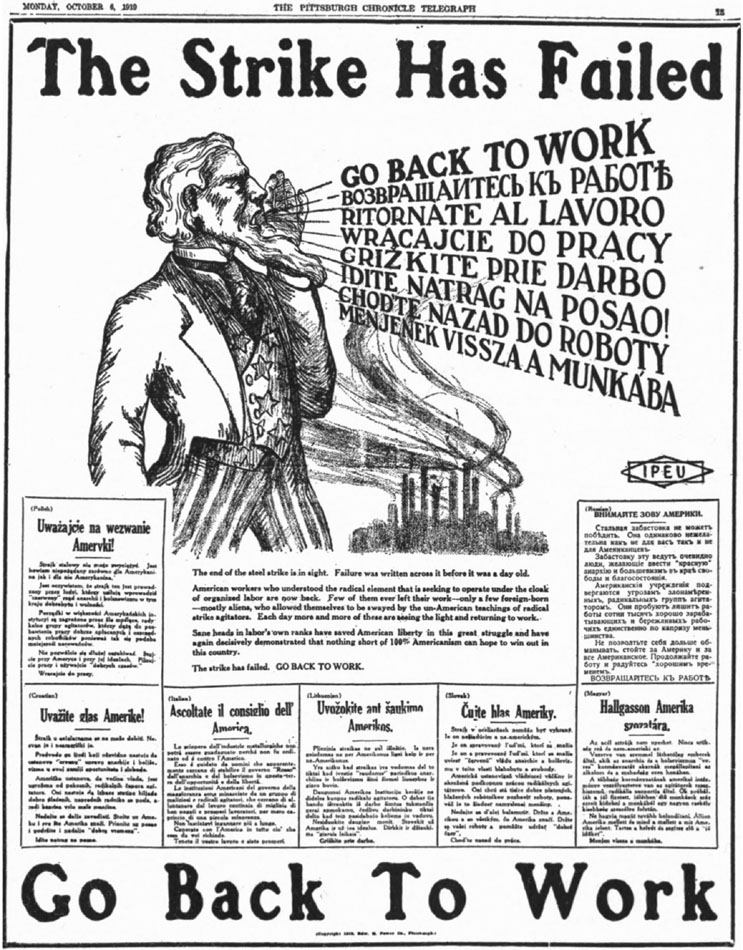

STEEL TRUST NEWSPAPER PROPAGANDA

Pittsburgh Chronicle Telegraph, October 6, 1919.

In the meantime, Secretary Conboy arriving upon the scene, the two of us started to the Mayor’s office to protest, when suddenly, in broad daylight, at a main street corner in the heart of the city, a mob of about forty men rushed us. Shouldering me away from Mr. Conboy, they stuck guns against my ribs and took me to the depot. While there they made a cowardly attempt to force me to sign a Back-To-Work card, which meant to write myself down a scab. Later I was put aboard an eastbound train. Several of the mob accompanied me to Conemaugh, a few miles out. The same night this “Citizens’ Committee,” with several hundred more, surrounded the organizers in their hotel and gave them twenty-four hours time to leave town. The city authorities refused to stir to defend them, and the following day organizers T. J. Conboy, Frank Hall, Frank Butterworth, and Frank Kurowsky were compelled to go. Domenick Gelotte, a local organizer of the miners, refused to depart and was promptly arrested. Up to this time the strike had been perfectly peaceful. The shut-down was so thorough that not even a picket line was necessary.

The mob perpetrating these outrages (duly praised by the newspapers as examples of 100 per cent. Americanism) was led by W. R. Lunk, secretary of the Y. M. C. A., and H. L. Tredennick, president of the chamber of commerce. This pair freely stated that the strike could never be broken by peaceful means, and that they were prepared to apply the necessary violence, which they did. Of course, they were never arrested. Had they been workers and engaged in a similar escapade against business men, they would have been lucky to get off with twenty years imprisonment apiece.

After a couple of weeks the organizers returned to Johnstown. Their efforts at holding the men together were so fruitful that the Cambria Company, in its own offices, organized a new mob to drive them out again. But this time, better prepared, they stood firm. On November 29, when the fresh deportation was to take place, Secretary Conboy demanded that Mayor Francke give him and the others protection. He offered to furnish the city a force of 1000 union ex-service men to preserve law and order. This offer was refused, and the Mayor and Sheriff reluctantly agreed to see that peace was kept. They informed the business men’s mob that there was nothing doing. It was a tense situation. Had the threatened deportation been attempted, most serious trouble would surely have resulted.

In the meantime numbers of the State Constabulary had been sent into town (the city and county authorities denying responsibility for their presence) and they terrorized the workers in their customary, brutal way. Eventually the result sought by all this outlawry developed; a break occurred in the ranks of the highly-paid, skilled steel workers. Although small at first, the defection gradually spread as the weeks rolled on, until, by January 8, about two-thirds of the men had returned to work.

Considered nationally, strike sentiment continued strong until about the middle of the third month, when a feeling of pessimism regarding the outcome began to manifest itself among the various international organizations. Consequently, a meeting of the National Committee was held in Washington on December 13 and 14, to take stock of the situation. At this meeting I submitted the following figures:

| Men on Strike | Men on Strike | |||||

| District | Sept. 29 | Dec. 10 | ||||

| 365,600 | 109,300 | |||||

| Estimated production of steel, 50 to 60 per cent. of normal capacity. | ||||||

| Pittsburgh | 25,000 | 8,000 | ||||

| Homestead | 9,000 | 5,500 | ||||

| Braddock-Rankin | 15,000 | 8,000 | ||||

| Clairton | 4,000 | 1,500 | ||||

| Duquesne-McKeesport | 12,000 | 1,000 | ||||

| Vandergrift | 4,000 | 1,800 | ||||

| Natrona-Brackenridge | 5,000 | 1,500 | ||||

| New Kensington | 1,100 | 200 | ||||

| Apollo | 1,500 | 200 | ||||

| Leechburg | 3,000 | 300 | ||||

| Donora-Monessen | 12,000 | 10,000 | ||||

| Johnstown | 18,000 | 7,000 | ||||

| Coatesville | 4,000 | 500 | ||||

| Youngstown district | 70,000 | 12,800 | ||||

| Wheeling district | 15,000 | 3,000 | ||||

| Cleveland | 25,000 | 15,000 | ||||

| Steubenville district | 12,000 | 2,000 | ||||

| Chicago district | 90,000 | 18,000 | ||||

| Buffalo | 12,000 | 5,000 | ||||

| Pueblo | 6,000 | 5,000 | ||||

| Birmingham | 2,000 | 500 | ||||

| Bethlehem Plants (5) | 20,000 | 2,500 | ||||

Owing to the chaotic conditions in many steel districts, it was exceedingly difficult at all times to get accurate statistics upon the actual state of affairs. Those above represented the very best that the National Committee’s whole organizing force could assemble. The officials of the Amalgamated Association strongly favored calling off the strike, but agreed that the figures cited on the number of men still out were conservative and within the mark. The opinion prevailed that the strike was still effective and that it should be vigorously continued.

On January 3 and 4, the National Committee met in Pittsburgh. At this gathering it soon became evident that the strike was deemed hopeless, so, according to its custom when important decisions had to be made, the National Committee called a special meeting for January 8, all the international organizations being notified. The situation was bad. Reliable reports on January 8 showed the steel companies generally to have working forces of from 70 to 80 per cent., and steel production of from 60 to 70 per cent. of normal. Possibly 100,000 men still held out; but it seemed merely punishing these game fighters to continue the strike. They were being injured by it far more than was the Steel Trust. There was no hope of a settlement, the steel companies being plainly determined now to fight on indefinitely. Therefore, in justice to the loyal strikers and to enable them to go back to the mills with clear records, the meeting adopted, by a vote of ten unions to five, a sub-committee’s report providing that the strike be called off; that the commissaries be closed as fast as conditions in the various localities would permit, and that the campaign of education and organization of the steel workers be continued with undiminished vigor.

At this point, wishing to have the new phase of the work go ahead with a clean slate, I resigned my office as Secretary-Treasurer of the National Committee. Mr. J. G. Brown was elected to fill the vacancy. The following telegram was sent to all the strike centers, and given to the press:

The Steel Corporations, with the active assistance of the press, the courts, the federal troops, state police, and many public officials, have denied steel workers their rights of free speech, free assembly and the right to organize, and by this arbitrary and ruthless misuse of power have brought about a condition which has compelled the National Committee for Organizing Iron and Steel Workers to vote today that the active strike phase of the steel campaign is now at an end. A vigorous campaign of education and reorganization will be immediately begun and will not cease until industrial justice has been achieved in the steel industry. All steel strikers are now at liberty to return to work pending preparations for the next big organization movement.

John Fitzpatrick,

D. J. Davis,

Edw. J. Evans,

Wm. Hannon,

Wm. Z. Foster.

The great steel strike was ended.

1. Youngstown Vindicator, November 24, 1919.

2. No history of the movement in the Youngstown district could be complete without some mention of the assistance rendered the workers by Bishop John Podea of the Roumanian Greek Catholic church, Youngstown, and Rev. E. A. Kirby, pastor of St. Rose Roman Catholic church of Girard, Ohio. Usually the churchmen (of all faiths) in the various steel towns were careful not to jeopardize the fat company contributions by helping the unions. But not these men. They realized that all true followers of the Carpenter of Nazareth had to be on the side of the oppressed steel workers; and throughout the entire campaign they distinguished themselves by unstinted co-operation with the unions. The service was never too great nor the call too often for them to respond willingly.

3. In connection with this matter it is interesting to note that after the strike had ended the union men entered suits against the steel companies for heavy damages. Up to the present writing the Lackawanna Steel Company, realizing the indefensibility of the outrages, has made out-of-court settlements to the extent of $22,500.

4. These Back-To-Work organizations were formed in many steel towns; their purpose was to recruit scabs. They were composed of company officials, business men and “loyal” workers. The companies furnished the wherewithal to finance them.