William Z. Foster

The Great Steel Strike and Its Lessons

LABOR’S LACK OF CONFIDENCE—INADEQUATE EFFORTS—NEED OF ALLIANCE WITH MINERS AND RAILROADERS—RADICAL LEADERSHIP AS A STRIKE ISSUE—MANUFACTURING REVOLUTIONS—STRIKES: RAILROAD SHOPMEN, BOSTON POLICE, MINERS, RAILROAD YARD AND ROAD MEN—DEFECTION OF AMALGAMATED ASSOCIATION

In preceding chapters I have said much about the injustices visited upon the steel workers by the steel companies and their minions; the mayors, burgesses, police magistrates, gunmen, State Police, Senate Committees, etc. But let there be no mistake. I do not blame the failure of the strike upon these factors. I put the responsibility upon the shoulders of Organized Labor. Had it but stirred a little the steel workers would have won their battle, despite all the Steel Trust could do to prevent it.

By this I mean no harsh criticism. On the contrary, I am the first to assert that the effort put forth in the steel campaign was wonderful, far surpassing anything ever done in the industry before, and marking a tremendous advance in trade-union tactics. Yet it was not enough, and it represented only a fraction of the power the unions should and could have thrown into the fight. The organization of the steel industry should have been a special order of business for the whole labor movement. But unfortunately it was not. The big men of Labor could not be sufficiently awakened to its supreme importance to induce them to sit determinedly into the National Committee meetings and to give the movement the abundant moral and financial backing so essential to its success. Official pessimism, bred of thirty years of trade-union failure in the steel industry, hung like a mill-stone about the neck of the movement in all its stages.

At the very outset this pessimism and lack of faith dealt the movement a fatal blow. When the unions failed to follow the original plan of the campaign (outlined in Chapter III) to throw a large crew of organizers into the field at the beginning and thus force a settlement with the steel companies during war time, as they could easily have done, they made a monumental blunder, one for which Organized Labor will pay dearly. Notwithstanding all their best efforts in the long, bitter organizing campaign and the great strike, the organizers could not overcome its effects. It was a lost opportunity that unquestionably cost the unionization of the steel industry.

And the same pessimism which caused this original deadly mistake made itself felt all through the steel campaign, by so restricting the resources furnished the National Committee as to practically kill all chance of success. Probably no big modern trade-union organizing campaign and strike has been conducted upon such slender means. Considering the great number of men involved, the viciousness of the opposition and the long duration of the movement (18 months), the figure cited in the previous chapter as covering the general expenses, $1,005,007.72, is unusually low. It amounts to but $4.02 per man, or hardly a half week’s strike benefits for each. Compared to the sums spent in other industrial struggles, it is proportionally insignificant. For example, in the great coal miners’ strike in Colorado, begun September 23, 1913, and ended December 10, 1914, the United Mine Workers are authoritatively stated to have spent about $5,000,000.00 As there were on an average about 12,000 strikers, this would make the cost somewhere about $400.00 per man involved. And in those days a dollar was worth twice as much as during the steel strike. Had a fraction of such amounts been available to the steel workers they would have made incomparably a better fight.

The unions affiliated with the National Committee have at least two million members. Even if they had spent outright the total sum required to carry on the organizing campaign and strike it would not have strained them appreciably. But they did not spend it, nor any considerable part of it. In the previous chapter we have seen that with donations from the labor movement at large, and initiation fees and dues paid in by the steel workers, the movement was virtually self-sustaining as far as the co-operating unions were concerned—taking them as a whole. Now, in the next campaign, all that must be different. The unions will have to put some real money in the fight. Then they may win it.

When I say that there was a shortage of resources in the steel campaign I include particularly organizers from the respective international unions. Of these there were not half enough. Often the National Committee had to beg for weeks to have a man sent in to organize a local union, the members for which it had already enrolled. Hundreds of local unions suffered and many a one perished outright for want of attention. Whole districts had to be neglected, with serious consequences when the strike came.

Moreover, the system used by many internationals in handling their organizers was wrong. They controlled them from their several general headquarters, shifting them around or pulling them out of the work without regard to the needs of the campaign as a whole. This tended to create a loose, disjointed, undisciplined, inefficient organizing force. It was indefensible. Now, in the next drive there are two systems which might be used. (1) The international unions could definitely delegate a certain number of organizers to the campaign and put them entirely under the direction of the National Committee. This was the plan followed by the A. F. of L., the Miners, and the Railway Carmen. It worked well and tended to produce a homogeneous, well-knit, controllable, efficient organizing force. (2) The organizers definitely assigned to the steel campaign by the internationals could be formed into crews, each crew to be controlled by one man and charged with looking after the needs of its particular trade. The Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, Machinists, and Electrical Workers used this system to some extent. A series of such crews, working vertically along craft lines while the National Committee men worked horizontally along industrial lines, would greatly strengthen the general movement. When the strike came it would not only be an industrial strike but twenty-four intensified craft strikes as well. Of the two systems, the first is probably the better, and the second, because of the individualism of the unions, the more practical. Either of them is miles superior to the plan of controlling the field organizers from a score of headquarters knowing very little of the real needs of the situation.

But more than men and money, the steel workers in their great fight lacked practical solidarity from closely related trades. In their semi-organized condition they were unable to withstand alone the terrific power of the Steel Trust, backed by the mighty capitalistic organizations which rushed to its aid. They needed from their organized fellow workers help in the same liberal measure as Mr. Gary received from those on his side. And help adequate to the task could have come only by extending the strike beyond the confines of the steel industry proper.

When the steel unions end their present educational campaign and launch the next big drive to organize the steel workers (which should be in a year or two) they ought to be prepared to meet the formidable employer combinations sure to be arrayed against them by opposing to them still more formidable labor combinations. The twenty-four unions should by then be so allied with the miners’ and railroad men’s organizations that should it come to a strike these two powerful groups of unions would rally to their aid and paralyse the steel industry completely by depriving it of those essentials without which it cannot operate, fuel and rail transportation. How effective such assistance would be was well indicated by the speedy and wholesale shutting down of steel mills, first during the general strike of bituminous miners in November and December of 1919, and then during the “outlaw” railroad strike in April, 1920. With such a combination of allied steel, mine and railroad workers confronting them, there is small likelihood that the steel companies (or the public at large) would consider the question of the steel workers’ right to organize of sufficient importance to fight about. Mr. Gary might then be brought to a realization that this is not Czarist Russia, and that the men in his mills must be granted their human rights.

That the miners and railroaders have sufficient interests at stake to justify their entrance into such a combination no union man of heart will attempt to deny. Not to speak of the general duty of all unionists to extend help to brothers in trouble, the above-mentioned groups have the most powerful reasons of their own to work for the organization of the steel industry. The United States Steel Corporation and so-called “independent” steel mills are the stronghold of industrial autocracy in America. Every union in the labor movement directly suffers their evil effects in lower wages, longer hours and more difficult struggles for the right to organize than they otherwise would have. No union will be safe until these mills are under the banner of Organized Labor. Beyond question the organization of the steel workers would tremendously benefit the miners and railroaders. The latter cannot possibly do too much to assist in bringing it about. It is their own fight.

For the miners and railroad men to join forces with the steel workers would mean no new departure in trade-unionism. It would be merely proceeding in harmony with the natural evolution constantly taking place in the labor movement. For instance, to go no further than the two industries in question, it is only a few years since the miners negotiated agreements and struck, district by district. Even though one section walked out, the rest would remain at work. And as for the railroaders, they followed a similar plan upon the basis of one craft or one system. Each unit of the two industries felt itself to be virtually a thing apart from all the others when it came to common action against the employers. It was the heyday of particularism, of craft unionism complete. And anyone who did not think the system represented the acme of trade-union methods was considered a crank. But both groups of organizations are fast getting away from such infantile practices. We now find the miners striking all over the country simultaneously, and the railroad men rigging up such wide-spreading combinations among themselves that soon a grievance of a section hand in San Diego, California will be the grievance of an engineer in Bangor, Maine. The man who would advocate a return to the old method of each for himself and the devil take the hindmost would be looked upon today, to say the least, with grave suspicion.

During the recent steel strike the National Committee tried to arrange a joint meeting with the officials of the miners and railroad brotherhoods to see if some assistance, moral if nothing else, could be secured for the steel workers. But nothing came of it. In the next big drive, however, these powerful organizations should be allied with the steel workers and prepared to give them active assistance if necessary. And in the tuning and timing of movements to permit of such a condition, so that no lots, legal or contractual, need be cut across, there are involved no technical problems which a little initiative and far-sightedness on the part of the labor men in control could not readily overcome.

In order to cover up their own inveterate opposition to Organized Labor in all its forms and activities, and to blind the workers to the real cause of the defeat, namely lack of sufficient power on the employees’ side, great employing interests caused to be spread over the whole country the statement that the steel strike failed because of radical leadership, and that if such “dangerous” men as John Fitzpatrick and myself had not been connected with it everything would have been lovely. They were especially severe against me for my “evil” influence on the strike. But somehow their propaganda did not seem to strike root among labor men, especially those who were backing the steel campaign. The workers are getting too keen these days to let the enemy tell them who shall or shall not be their officials; and when they see one of these officials made the target of bitter attack from such notorious interests as the Steel Trust they are much inclined to feel that he is probably giving them a square deal.

As for myself, and I know John Fitzpatrick took the same position regarding himself, I was willing to resign my position on the National Committee the very instant it was indicated by those associated with me that my presence was injuring the movement. I felt that to be my duty. But to the last, that indication never came. When I finally resigned as Secretary-Treasurer on January 31, it was entirely of my own volition.

The avalanche of vituperation and personal abuse was started several months before the strike, when a traitor labor paper in Pittsburgh (one of the stripe which lives by knifing strikes and active unionists for the employers) published articles containing quotations from the “red book,” and the other stuff later bruited about in the daily press. To hear this sheet tell it, the revolution was at hand. Immediately after the articles appeared I sent copies to the presidents of all the twenty-four co-operating unions, with the result that almost all of these officials wrote me, advising that I pay no attention to these attacks, but continue with my work. They seemed to consider it something of a compliment to be so bitterly assailed from such a quarter. Again, at the very moment when President Gompers was dictating his letter to Judge Gary asking for a conference (long after the above-mentioned attacks) I stated that possibly too much prominence for me in the movement might attract needless opposition to it and I offered to resign from the conference committee which handled all negotiations concerning the steel strike. But my objections were over-ruled and I was continued on the committee. Moreover, at any time in the campaign a word from the executive officers of the A. F. of L. would have brought about my resignation. This they were aware of for months before the strike. All of which indicates that the men responsible for the organizations in the movement were satisfied that it was being carried on according to trade-union principles, and also that in consideration of the Steel Trust’s murderous tactics in the past it was a certainty that if the opposition had not taken the specific form it did, it would have manifested itself in some other way as bad or worse. It was to be depended upon that some means would have been found to thoroughly discredit the movement.

This conviction was intensified by the unexampled fury with which each important move of Labor during the past year has been opposed, not only by employers but by governmental officials as well. All through the war the moneyed interests watched with undisguised alarm and hatred the rapid advance of the unions; but they were powerless to stop it. Now, however, they are getting their revenge. The usual method of defeating such movements during this period of white terrorism is to attach some stigma to them; to question the legitimacy of their aims, and then, when the highly organized and corrupted press has turned public sentiment against them, to crush them by the most unscrupulous means. It makes no difference how mild or ordinary the movement is, some issue is always found to poison public opinion against it.

The first important body of workers to feel the weight of this opposition was the railroad shopmen. The Railroad Administration having dilly-dallied along with their demands for several months, these under-paid workers, goaded on by the mounting cost of living, finally broke into an unauthorized strike in the early summer of 1919. This almost destroyed the organizations. Officials who ought to know declared that at one time over 200,000 men were out. Naturally the press roundly denounced them as Bolsheviki. Upon a promise of fair treatment they returned to work. When the matter finally came to President Wilson for settlement, he declared that to raise wages would be contrary to the Government’s policy of reducing the cost of living, and requested that the demands be held in abeyance. This statement was a Godsend to all the reactionary elements, who used it to break up wage movements everywhere. Thus came to grief the effort of the shopmen. Up to May, 1920, they have secured no relief whatsoever.

Next came the affair of the Boston police in September, 1919. This developed from an effort of typically conservative policemen to organize. The strike was deliberately forced by the action of State politicians, inspired by big business, in cold-bloodedly discharging a number of the officers of the new union and stubbornly refusing to re-instate them. When the inevitable strike occurred they labelled it not merely an attempted revolution, but a blow at the very foundations of civilization. The press did the rest. The strike was buried beneath a deluge of abuse, misrepresentation and vilification.

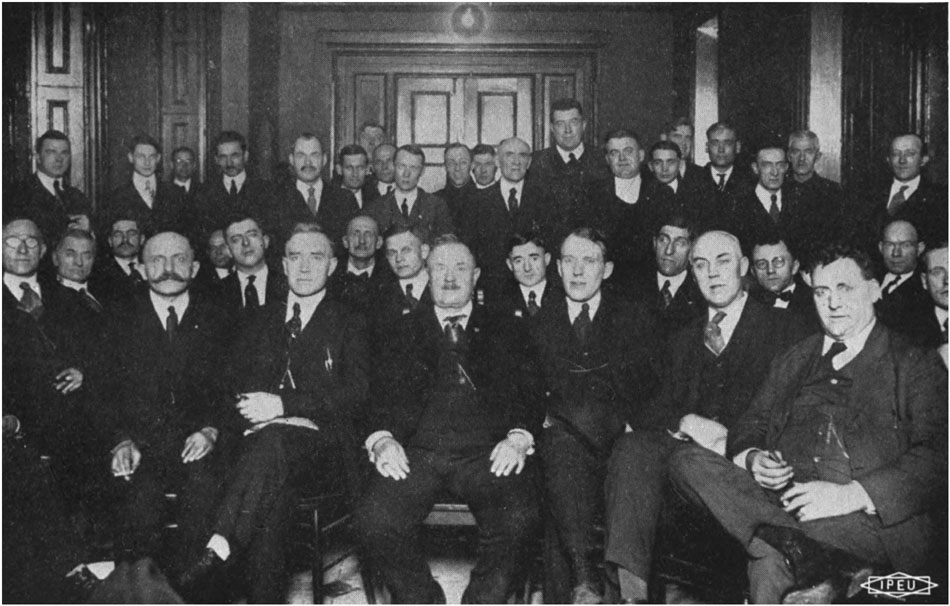

A GROUP OF ORGANIZERS

Standing, left to right: W. Searl, F. Wilson, A. V. Craig, M. Mestrovich, E. Martin, J. M. Peters, R. W. Beattie, J. Moskus, S. Coates, J. Manley, Striker, T. A. Harris, E. O. Gunther, B. J. Damich, Striker, C. Foley, M. Bellam, T. A. Daley, Striker, W. Z. Foster. Seated, left to right: J. Lenahan, F. J. Sweek, J. Klinsky, F. Wiernicki, I. Liberti, A. DeVerneuil, C. Claherty, J. N. Aten, J. W. Hendricks, S. Rokosz, R. W. Reilly, J. A. Norrington, F. Kurowsky, J. G. Brown, G. W. Troutman, J. E. McCadden, W. Murphy, S. T. Hammersmark.

Then came the coal miners in November, 1919. During the war this body of men sent fully 60,000 members to the front in France. They bought untold amounts of liberty bonds and worked faithfully to keep the industries in operation. But no sooner did they make demand for some of the freedom which they thought they had won in the war than they found themselves crowded into a strike, and their conservative, old-line, trade-union leaders harshly assailed as revolutionists. For instance, said Senator Pomerene:(1)

Years ago the American spirit was startled because a Vanderbilt had said, “The public be damned.” But Vanderbilt seems to have no patent on the phrase, or if he had it is being infringed today by men who have as little regard for the public welfare as he himself had. There is no difference in kind between him and a Foster, who, aided by the extreme Socialist and I. W. W. classes of the country, aims to enlist under his leadership all the iron and steel workers of a nation and to paralyze industry, or a Lewis (President of the United Mine Workers of America), who, to further his own ambitions, aided as he was by the same elements, calls 400,000 men out of the mines and says to the public, “Freeze or starve.”

The Government condemned the strike as “unjustifiable and unlawful” and invoked against it the so-called Lever law. This law, a war measure against food and fuel profiteers, was, when up for adoption, distinctly stated by its author, Representative Lever, and by Attorney General Gregory, as not applying to workers striking for better conditions.(2) Moreover, since the armistice it had fallen into disuse,—as far as employers were concerned; but upon the strength of it the miners’ strike was outlawed, Federal Judge Anderson issuing an injunction which commanded the union officials to rescind the strike order and to refuse all moral and financial assistance to the strikers. Rarely has a labor union found itself in so difficult a situation. The only thing that saved the miners from a crushing defeat was their splendid organization and strategic position in industry. On November 11, after the union officials had agreed to rescind the strike order, the Philadelphia Public Ledger expressed an opinion widely held when it said:

The truth of the matter is that we all “got it wrong” on this coal situation. This is the time to say in entire frankness that the Government handled the situation with the tact, timeliness and conciliatory spirit of a German war governor jack-booting a Belgium town into docility.

And now we have the unauthorized strike of the Railroad yard and road men; this is clearly an outbreak of workers exasperated on the one hand by a constantly increasing cost of living, and on the other by dilatory methods of affording relief. The orthodox tactics are being employed to break it. The Lever law, disinterred from the legislative graveyard to beat the miners, has been galvanized into life again and is being used to jail the strike leaders. This is not all, however. Probably there never was a big strike in this country more spontaneous and unplanned than the one in question. But that does not worry our Department of Justice; it has just announced to a credulous world that the whole affair is a highly organized plot to overthrow the Government. Within the hour I write this (on April 15) I read in the papers that I have been singled out by Attorney-General Palmer as one of the strike leaders. Eight-column headlines flare out the charge, “PALMER BLAMES FOSTER FOR RAIL STRIKE,” etc.(3)

To Mr. Palmer’s “penny dreadful” plot, the local newspapers add lying details of their own. The Pittsburgh Leader, for instance, recites in extenso how I returned from the West in disguise to Pittsburgh several days ago—presumably after a trip plotting with Mr. Palmer’s wonderful revolutionaries, who not only can bring whole industries to a standstill by a wave of the hand, but can do it in such a manner that although many thousands of workers are “in the know” the Department of Justice never gets to hear about it until the strikes have occurred.

Now the fact is that I have been so busy writing this book that I have hardly stirred from the house for weeks. Since the steel strike ended I have not been beyond the environs of Pittsburgh. Moreover, I do not know a solitary one of the men advertised as strike leaders, nor has there been any communication whatsoever between us. I have not attended any strike meetings, nor have I even seen a man whom I knew to be a striker. But of course such details are irrelevant to the Department of Justice and the newspapers. The latter boldly announce that it is officially hoped that Mr. Palmer’s charges will stampede the men back to work.(4) In fact that is their aim. These charges are a strike-breaking measure, pure and simple, and have no necessary relation to truth.(5)

Similar instances might be multiplied to illustrate the extreme virulence of the attacks on Labor in late struggles—how the press manufactured the general strikes in Seattle and Winnipeg into young revolutions; and how even when Mr. Gompers announced some time back that the American Federation of Labor would continue its customary political policy of “rewarding its friends and punishing its enemies,” the scheme was denounced in influential quarters as an attempt to capture the Government and set up a dictatorship of the proletariat. But enough. The steel strike was a drive straight at the heart of industrial autocracy in America; it could expect to meet with nothing less than the most desperate and unscrupulous resistance. If the issue used against the strike had not been the charge of radical leadership, we may rest assured there would have been another “just as good.” The next movement will have to win by its own strength, rather than by the vagaries of a newspaper-created public opinion.

But a far more pressing problem even than any of those touched upon in the foregoing paragraphs is the one involved in the attitude of the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers toward the steel campaign. This organization withdrew from the National Committee immediately after the strike was called off, and it has apparently abandoned trying, at least for the time being, to organize the big steel mills. Thus the whole campaign is brought to the brink of ruin, because the Amalgamated Association has jurisdiction over about 50 per cent. of the workers in the mills, including all the strategic steel-making trades, without whose support the remainder cannot possibly win. Unless it can be brought back to the fold, the joint movement of the trades in the steel industry will almost certainly be broken up, to the great glee of Mr. Gary and his associates.

This action was in logical sequence to the position taken through the campaign by several of the Amalgamated Association’s general officers. From the beginning, they considered the movement with pessimism, often with hostility. It received scant co-operation from them. As related in Chapter VI, they tried to get a settlement with the U. S. Steel Corporation right in the teeth of the general movement; and their financial support was meager, to say the least.(6) For a few weeks during the strike movement, when victory seemed near, they displayed some slight enthusiasm; but this soon wore off and they adopted a policy of “saving what they could.” They were exceedingly anxious to call off the strike many weeks before its close, and went about the country discouraging the men and advising them to return to work. And even worse, they attempted to make separate settlements with the steel companies. The following proposed agreement, presented to (and refused by) the Bethlehem Steel Corporation at Sparrows’ Point when the strike was not yet two months old, tells its own story:

November 19th, 1919.

Agreement entered into between the Bethlehem Steel Company of Sparrows’ Point, Maryland, and its employees, governing wages and conditions in the Sheet and Tin mills, and Tin House Department.

1. It is agreed that the wages and conditions agreed upon between the Western Sheet and Tin Plate Manufacturers’ Association and the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers, as agreed upon in the Atlantic City Conference, June, 1919, will be the prices and conditions paid to the employees in the above-mentioned departments.

2. That the company will also agree to the re-instatement of all their former employees, such as seek employment without any discrimination.

3. The above Agreement to expire June 30th, 1920.

During the strike the general officers of the Amalgamated Association never tired of telling how sacred they considered their contracts with the employers, and did not hesitate to jeopardize the strike by living up to them most strictly. But when it came to their obligations to the other trades it was a different story. They well knew, when they tried to make separate settlements with the U. S. Steel and Bethlehem Companies, that they were violating solemn agreements which they had entered into with the other trades in the industry, not to speak of fundamental principles of labor solidarity.

The national officials in question looked with undisguised jealousy upon the growth to importance of other unions in the industry where their own organization had operated alone so long. They lost no love on the National Committee. In fact more than one of their number seemed to take particular delight in placing obstructions in its way. If they wanted to see the steel industry organized they certainly showed it in a peculiar manner. A goodly share of my time—not to speak of that of others—was spent plugging the holes which they punched through the dike. And apparently they always had the hearty support of their fellow officers. It is only fair to say, however, that the lesser officials and the rank and file of the Amalgamated Association strongly favored the National Committee movement and gave it their loyal cooperation.

As a justification for the Amalgamated Association officials’ action in quitting the joint campaign, word is being sent through the steel industry that henceforth that organization will insist upon its broad jurisdictional claims and become an industrial union in fact, taking into its ranks and protecting workers of all classes in the steel industry. But no one familiar with the Amalgamated Association will take this seriously. It is a dyed-in-the-wool skilled workers’ union, and has been such ever since its foundation forty-five years ago. Its specialty is the “tonnage men,” or skilled iron and steel making and rolling trades proper. All its customs, policies and instincts are inspired by the interests of this industrial group. It has never looked after the welfare of the mechanical trades and the common laborers, even though for the past few years it has claimed jurisdiction over them. In its union mills it is the regular thing to find only the tonnage men covered by the agreements, no efforts whatever being made to take care of the other workers. It is true that during the recent campaign, due to the stimulus of the National Committee, laborers were taken in; but of the way they were handled, probably the less said the better. The incidents related in Chapter X are typical.

That the men now at the head of the Amalgamated Association will upset these craft practices and revolutionize their organization into a bona fide, vigorous industrial union is incredible to those who have seen them in action. But even if the miracle happened, even if they got rid of their mid-nineteenth century ideas and methods, adopted modern principles and systems, and put on the sweeping campaign necessary to organize the industry, it would not solve the problem. The other unions in the steel industry are not prepared to yield their trade claims to the Amalgamated Association, and any serious attempt by that organization to infringe upon them would result in a jurisdictional quarrel, so destructive as to wreck all hope of organizing the industry for an indefinite period. The unions would be so busy fighting among themselves that they would have no time, energy or ambition to fight the Steel Trust.

Progress and organization in the steel industry are to be achieved not by splitting the ranks and dividing the forces, but by consolidating and extending them. The only rational hope in the situation lies in a firm federation of all the trades in the industry, allied with the miners and railroad men in such fashion that they will extend help in case of trouble. The steel workers are fast recovering from their defeat. The educational campaign is getting results, and the work should be made a permanent institution until the industry is organized. For the Amalgamated Association to desert the field now is suicidal. It is worse; it is a crime against the labor movement. It will break up the campaign and throw the steel workers, helpless, upon the mercy of Gary and his fellow exploiters. Organized Labor should not permit it. The time is past when a few short-sighted union officials can block the organization of a great industry.

1. Quoted from The Coopers’ Journal for February, 1920.

2. For important details, see article entitled “The Broken Pledge,” by Samuel Gompers, in the American Federationist, January, 1920.

3. Pittsburgh Post, April 15, 1920.

4. Pittsburgh Chronicle-Telegraph, April 15, 1920.

5. In connection with this matter I promptly called Mr. Palmer a liar, a statement which was widely carried by the press. Our would-be tyrant swallowed it. In the situation two courses were open to him: If his accusations against me were true, under his own interpretation of the Lever law he was duty-bound to arrest me; and if they were not true, common justice demanded that he admit the incorrectness of the statements he had sent flying through the press, attacking me. But he has done neither. And in the meantime I have been subjected to a storm of journalistic abuse. For example, says the Donora, Pa. Herald of April 16: “Wm. Z. Foster seems determined to have that little revolution if he has to get out and start one himself. About the best remedy for that bird would be one of those old-fashioned hangings.”

One can readily imagine how quickly the wheels of justice would hav1.irled and how speedily the editor would have been clapped into jail were such an incitement to murder printed in a labor journal. But When the case in point was called to the attention of the Pittsburgh officials of the Department of Justice they could do nothing about it. Nor could those of the Post Office Department, although the Donora Herald circulates through the mails. Similarly the county and state officials could see no cause for action. Finally the opportunities for relief sifted down to a libel suit. And what chance has a workingman in such a suit against a henchman of the Steel Trust in the heart of Pennsylvania’s black steel district?

6. In the report included at the end of Chapter VI, the Amalgamated Association is shown to have enrolled 70,026 members during the campaign. But, for the reasons cited, the figure is far too low. President Tighe gave a better idea of the number when, testifying before the Senate Committee, he said (Hearings, page 353) that the secretary had told him “that he had already issued in the neighborhood of 150,000 dues cards,” and could not get them printed fast enough. For each man of this army of members, the national headquarters of the Amalgamated Association received two dollars. Yet in return the officials in charge, throughout the entire movement, gave the National Committee directly only $11,881.81 to work with. Of this, $3,881.81 was for organizing expenses, and $8,000.00 was to feed and furnish legal help to the great multitudes of strikers, half of whom were members of the Amalgamated Association. What strike help was extended in other directions was correspondingly scanty. The balance of the funds taken in is still in its treasury.