|

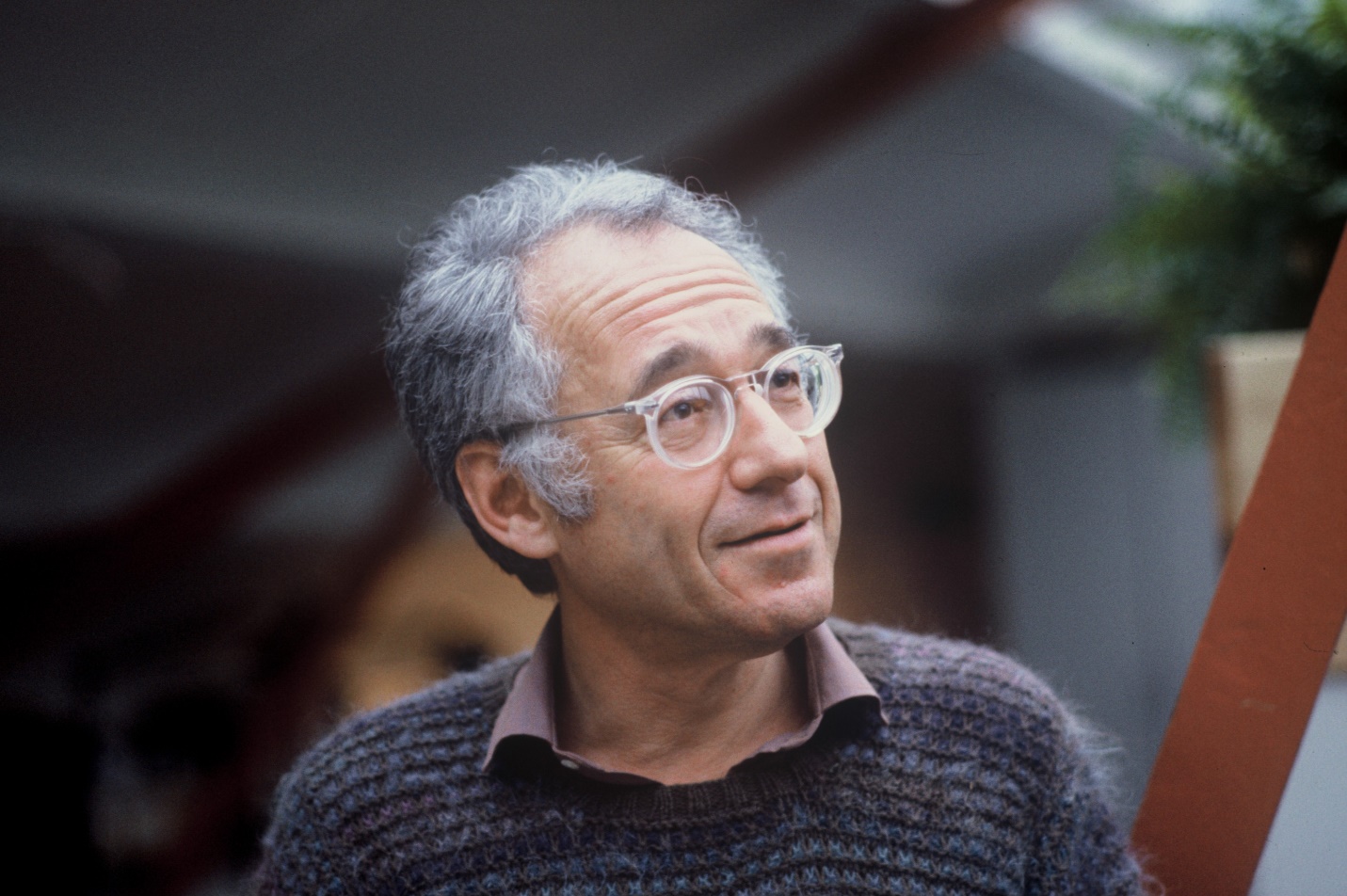

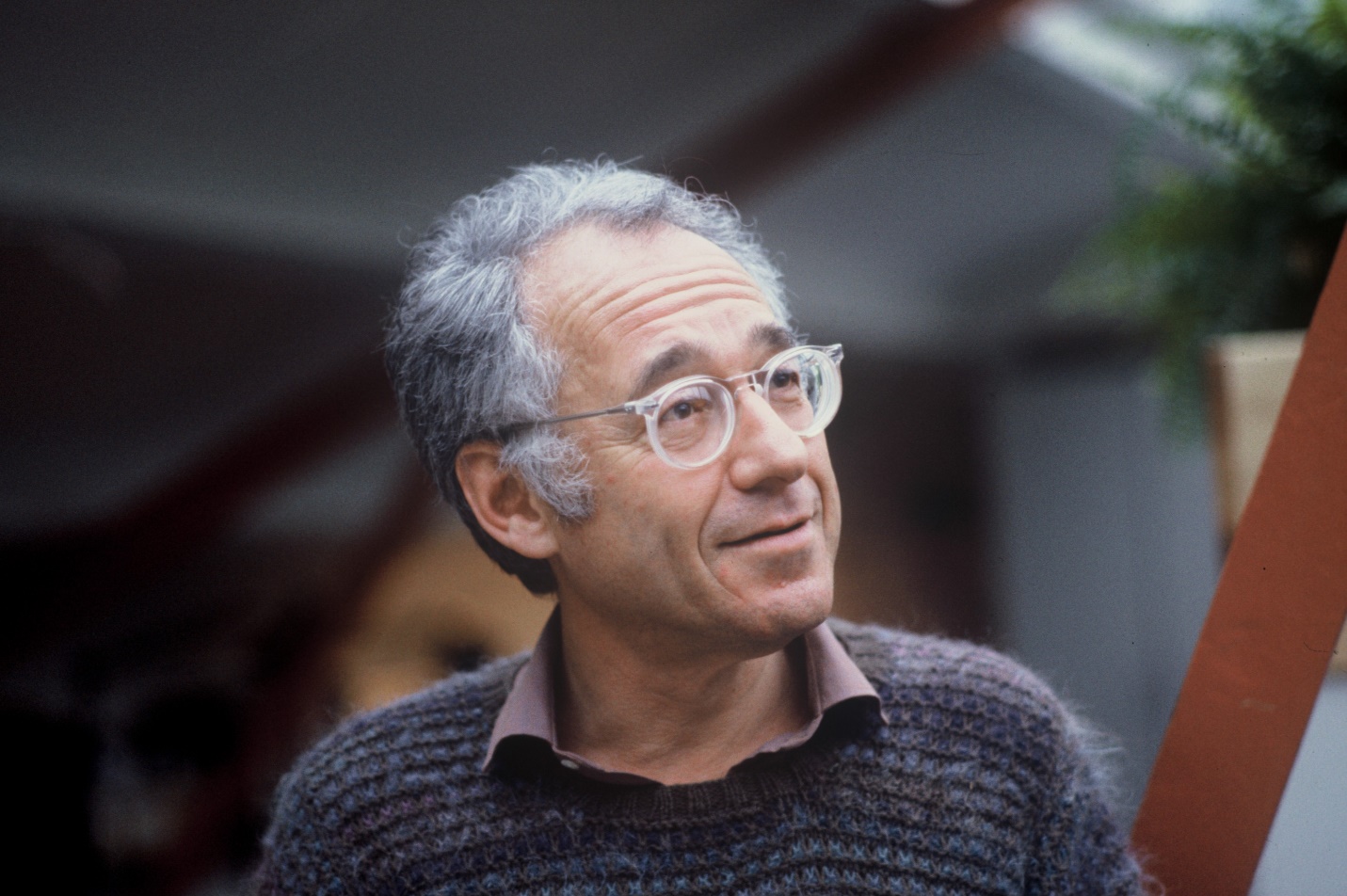

Michael Kidron (1930–2003) was born in Cape Town into an ardently Zionist family. At the age of 15 he travelled on his own to Palestine to join his family, who had already gone on ahead. He soon rejected Zionism and, after studying economics at the Hebrew University, went on to Oxford.

In Britain he quickly joined up with his brother-in-law Tony Cliff, whose theoretical analysis of the USSR as a state capitalist regime was a definitive rejection of the orthodox Trotskyist analysis then prevalent on the non-communist revolutionary left. Together they were the mainstays of the tiny Socialist Review group in the 1950s and early 1960s, as it grew into the International Socialists (IS) in the 1960s and 1970s. Intellectually and in every other way Kidron proved to an equal to the older and more experienced Cliff, and in the early years they complemented each other perfectly. They helped build a political movement around the belief that socialism was both necessary and possible, but that it could only come about through the self-activity of the working class in the developed capitalist world.

It was well summed up in the slogan of the time: “Neither Washington nor Moscow, but International Socialism.”

Kidron contributed scores of articles to Socialist Review right the way through to 1962 when it ceased publication, its role as a theoretical organ being taken over and expanded by the journal International Socialism, and its more immediate agitational work by the trade-union orientated Industrial Worker (soon renamed Labour Worker). He did not only write theory – a glance at his bibliography will show that he was also a first-rate propagandist and activist. He was also a successful editor of Socialist Review for a number of years, only leaving that role in 1960 to take up the editorship of the new theoretical journal International Socialism. Kidron remained as editor of International Socialism up to 1965 – and these years were a part of what Ian Birchall has described as “the golden age of the journal”.

In these years, he combined organizational and activist work with intellectual and academic work of a high order. This included both path-breaking research on Indian and Pakistani economic development in particular, and innovative Marxist theoretical work explaining the long post-war boom of western capitalism through the theory of the permanent arms economy.

Kidron is best known as a Marxist economist, and according to Chris Harman, he was “probably the most important Marxist economist of his generation”. His work in explaining the role of arms expenditure in the temporary stability of post-war capitalism was ground-breaking, and became a cornerstone of IS theory. But while he was developing theories to explain what was happening in Western capitalism, he was also developing theories to explain events in the Third World. In particular, he argued that Lenin’s theories on imperialism, that might have been appropriate when they were first written, no longer fitted the world of the sixties.

Kidron’s work in these two areas, and others, was developed in a series of articles published in the press of the Socialist Review Group/International Socialists and in two books Western Capitalism Since the War (1968) and Capital and Theory (1974). All of his major writings have just been republished by Haymarket Books as Capitalism and Theory: Selected Writings of Michael Kidron (2018).

If being an admired Marxist economist and activist was not enough, Kidron was also an inspirational educator and mentor to a generation of activists. As his colleague and friend Ronald Segal wrote at the time of his death, “he was a revolutionary and an intellectual who never discarded people for ideas”.

IS responded to the events of 1968, after an impassioned debate in which more “Luxemburgist” or libertarian idea of organisation were seen off, by orienting more directly to certain Leninist, democratic centralist ideas about revolutionary organization. While Kidron endorsed what he termed “the transition from a propaganda-and-protest organization to a political one”, he was increasingly uneasy about organizational developments and the failure of the IS’s theory to remain as lively, lucid and responsive as it had once been. In the mid-1970s, he distanced himself from IS and in July 1977 he wrote a critical article for the 100th issue of International Socialism. In this he questioned not only certain theoretical groundings of the organisation but also his own personal contribution to the theory of the Permanent Arms Economy.

In the meantime, he (and his partner Nina) joined Pluto Press and helped transform it into the most engaged and politically successful of the UK’s left publishing houses in this period. Apart from inspirational editorial input (which included the series of Workers’ Handbooks, Big Red Diaries and radical playscripts), Kidron returned to his own analytical writings, now chronicling changes in the world system graphically in the highly innovative The State of the World Atlas, co-authored with Ronald Segal (1981), and in The War Atlas, co-authored with Dan Smith (1983).

At the end of the 1980s, Kidron turned his intellectual energies and enthusiasms in further directions, linking the economic underpinnings of the capitalist system to its disastrous environmental impacts, on the one hand, and its effects on the individual psyche, on the other. Alas, Presence of the Future: The Costs of Capitalism and the Transition to Ecological Society was to remain an unwieldy, unfinished manuscript. Two chapters, however, were polished by Mike for publication in 2002, one in the Socialist Register the other in International Socialism Journal. A further essay, Paradox upon Paradox: Fractal States and Their Making was extracted and edited from Chapter 5 of the book and published posthumously in International Socialism Journal in 2020.

A forceful, freethinking and warm personality combined with acute economic and political insight and an undying belief in the cause of human liberation. It is no wonder he was one of the most important figures of his generation of socialist activists.

Last updated on 9 May 2022