We must dwell in greater detail on the data of the 1894-95 census on incomes from handicrafts. The attempt to collect household data on incomes is very instructive, and it would be quite wrong to confine ourselves to general “averages” for the sub-groups (given above). We have already, on more than one occasion, referred to the fictitious nature of “averages” derived by adding together individual handicraftsmen and owners of big establishments and then dividing the total obtained by the number of the components. Let us endeavour to assemble the data contained in the Sketch on this subject in order to illustrate this method clearly and prove its fictitious nature and to demonstrate that in scientific investigations and in analysing house-to-house census data handicraftsmen must be grouped in categories according to number of workers (family and wage-workers) employed in the workshop, and all the census data arranged in accordance with these categories.

The compilers of the Sketch must have noted the all too obvious fact of higher incomes in the big establishments, and tried to minimise its significance. Instead of giving precise census data on the large establishments (which they could have selected with no difficulty), they again confined themselves to general discussions, arguments and inventions against conclusions which the Narodniks find unpleasant. Let us examine these arguments.

“If in such” (big) “establishments we meet with a family income disproportionately larger than that of the small establishments, we must not lose sight of the fact that a considerable part of this income is mainly the reproduction of the value, firstly, of a certain portion of the fixed capital transmitted to the product, secondly, of the labour and expenses connected with commerce and transport which play no part in production, and, thirdly, of the value of food supplied to wage-workers who receive their board from the masters. These facts” (facts, indeed!) “limit the possibility of certain illusions arising which give an exaggerated notion of the advantages of wage-labour in handicraft industry or, what amounts to the same thing, of the capitalist element” (p. 15). That it is highly desirable in all investigations “to limit” the possibility of illusions is something which nobody, of course, doubts, but for this it is necessary to combat “illusions” by means of facts, facts taken from the household census, and not by citing one’s own opinions, which are themselves sometimes mere “illusions.” Is not, indeed, the authors’ argument about commercial and transport expenses an illusion? Who does not know that these expenses per unit of product are far smaller for the big producer than the small producer,[1] that the former buys his material cheaper and sells his product dearer, knowing how (and being in a position) to choose time and place? The handicraft census, too, mentions these generally known facts—cf. pp. 204 and 263, for example—and one cannot but regret that the Sketch contains no facts about expenses on the purchase of raw materials and the sale of the product by big and small industrialists, by handicraftsmen and buyers up. Further, as regards the wear and tear of fixed capital, here again the authors, while combating illusions, are themselves the victims of an illusion. Theory tells us that large expenditures on fixed capital diminish the part of the value per unit of product that represents wear and tear and is transmitted to the product. “An analysis and comparison of the prices of commodities produced by handicrafts or manufactures, and of the prices of the same commodities produced by machinery, shows generally that, in the product of machinery, the value due to the instruments of labour increases relatively, but decreases absolutely. In other words, its absolute amount decreases, but its amount, relatively to the total value of the product, of a pound of yarn, for instance, increases” (Das Kapital, I<2, S. 406).[12] The census also reckoned the costs of production, which include (p. 14, point 7) “repair of tools and fixtures.” What reason is there to believe that omissions in the registration of this point are to be met with more frequently among the big than among the small masters? Would not rather the contrary be the case? As to board provided for wage-workers, there are no facts on this point in the Sketch at all: we do not know exactly how many workers board with their masters, how frequent are the omissions in the census on this point, how often agriculturist masters feed their wage-workers with produce from their farms, and how often the masters entered the workers’ board under expenditure on production. Similarly, no facts on the inequality in the length of the working period in the big and the small establishments are given. We do not deny that the working period in the big establishments is very likely longer than in the small ones, but, firstly, the differences in income are out of all proportion to the differences in the length of the working period; and, secondly, it remains to be stated that the Perm statisticians have been unable to offer a single weighty argument, based on precise data, against the precise facts of the house-to-house census (given below), and in support of the Narodnik “illusions.”

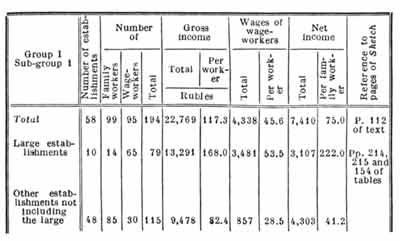

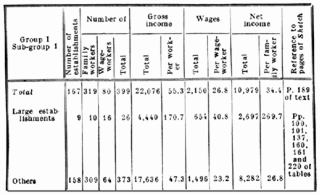

We have obtained the data for the large and small establishments in the following way: we examined the tables appended to the Sketch, noted the large establishments (wherever they could be picked out, that is, wherever they were not lumped together with the mass of establishments in a general total), and compared them with the general totals given in the Sketch for all the establishments of the same group and sub-group. This question is so important that we hope the reader will not reproach us for the numerous tables we give below: in tables the facts stand out more saliently and compactly.

Thus, the “average” income per family worker, 75 rubles, was obtained by adding together incomes of 222 rubles and 41 rubles. It appears that, after deducting the ten large establishments[2] with 14 family workers, the remaining establishments show a net income that is below the wages of a wage-worker (41.2 against 45.6 rubles), while in the large establishments wages are still higher. The productivity of labour in the large establishments is more than double (168.0 and 82.4 rubles), the earnings of a wage-worker nearly double (53 rubles and 28 rubles), while the net income is five times higher (222 and 41 rubles). Obviously, no talk about differences in the working period or any other argument can eliminate the fact that the big establishments have the highest labour productivity[3] and the highest income, while the small handicraftsmen, for all their “independence” (first sub-group: those who work independently for the market) and their tie with the land (Group I), earn less than wage-workers.

In the carpentry trade the “net income” of the first sub-group of Group I “averages” 37.4 rubles per family worker, whereas the average earnings of a wage-worker in the same sub-group are 56.9 rubles (p. 131). It is impossible to pick out the big establishments from the tables, but it can scarcely be doubted that this “average” income per family worker was obtained by combining the highly profitable establishments employing wage-workers (who, after all, are not paid 56 rubles for nothing) with the dwarf workshops of the small “independent” handicraftsmen, who get much less than a wage-worker.

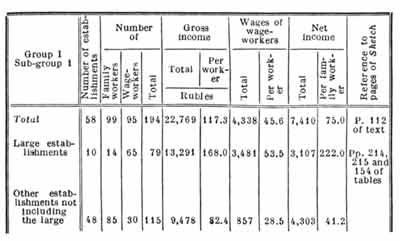

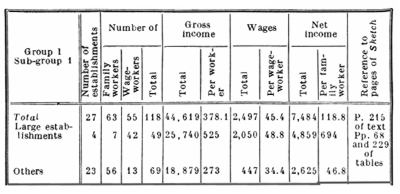

Next comes the bast-matting industry:

Thus, almost half the total output is concentrated in eleven of the ninety-nine establishments. In them, productivity of labour is more than double; the wages of the workers are also higher; and net income is more than six times the “average” and nearly ten times as high as that of the others, i.e., the smaller establishments. The latter have incomes but slightly higher than a worker’s wages (34 and 26 rubles respectively).

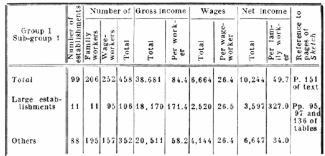

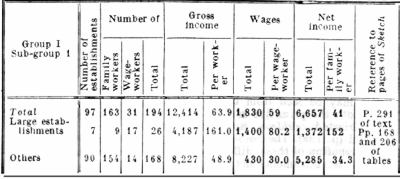

Rope and string industry[4] :

Thus, here too the general “averages” show a higher income for the family workers than for the wage-workers (90 against 65.6 rubles). But 4 of the 58 establishments account for over half the total output. In these establishments (capitalist manufactories of the pure type)[5] productivity of labour is almost three times the average (800 and 286 rubles) and over five times that of the remaining, i.e., smaller, establishments (800 and 146 rubles). Workers’ wages are much higher in the factories than in the small masters’ workshops (84 and 45 rubles). The net income of the manufacturers is over 1,000 rubles per family as compared with the “average” of 90 rubles and with the 60.5 rubles of the small handicraftsmen. The income of the small handicraftsman is, therefore, lower than a worker’s wages (60.5 and 65.6 rubles).

Although this industry is, in general, a small one that employs very few wage-workers (20%) we again find the same purely capitalist phenomenon of the superiority of the large (relatively large) establishments of the independent handicraftsmen in the agricultural group. And yet pitch and tar production is a purely peasant, “people’s” industry! In the large establishments labour productivity is over three times, workers’ wages about one-and-a-half times and net income about eight times the “average”; their net income, moreover, is ten times as high as that of other handicraft families who earn no more than the average wage-worker, and less than a wage-worker in the larger establishments. Let us note that pitch and tar production is chiefly a summer occupation, so that differences in the working period cannot be very great.[6]

Thus, here again, the averages for the entire sub-group are absolutely fictitious. The large establishments (of small capitalists) account for over half the total output, yield a net income six times the average and 14 times that of the small masters, and pay their workers wages exceeding the incomes of the small handicraftsmen. We do not mention productivity of labour; three or four of the large establishments produce a more valuable product—treacle.

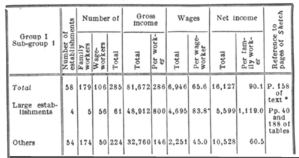

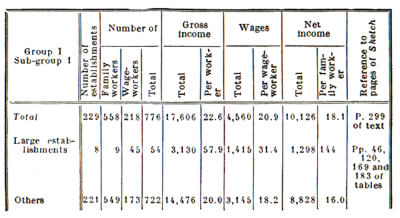

The pottery industry. Here again we have a typical small peasant industry with an insignificant number of wage-workers (13%), very small establishments (less than two workers per establishment) and a predominance of agriculturists. And here too we get the same picture:

Here, consequently, it is at once apparent from the “average” figures that the wage-worker’s earnings are higher than the family worker’s income. By treating the large establishments separately, we get the explanation of this contradiction, which we have already recorded in numerous instances. In the large establishments labour productivity, wages and masters’ incomes are all incomparably higher, while the small handicraftsmen get less than the wage-workers and less than half the earnings of the wage-workers in the best-organised shops.

Thus, here too, the “average” income of a family worker is lower than the earnings of a wage-worker. Here again it is to be explained by combining the big establishments—which are distinguished by a considerably higher labour productivity, higher payment of wage-workers, and a very high (comparatively) income—and the small establishments, the income of whose owners is about half the earnings of the wage-workers in the big establishments.

We might go on citing figures for other industries too,[7] but we think that those given are more than enough.

Let us now summarise the conclusions that follow from the facts examined:

1) The combining of large and small establishments results in absolutely fictitious “average” figures, which give no conception of the real state of affairs, obscure cardinal differences, and present as homogeneous something that is heterogeneous, of mixed composition.

2) The data for a number of industries show that the large establishments (where a large number of workers are engaged) are distinguished from the average and small establishments:

a) by an incomparably higher productivity of labour;

b) by better payment of wage-workers, and

c) by a far higher net income.

3) All the large establishments we have selected, without exception, employ wage-labour on an incomparably larger scale (than the average-sized establishments in the given industry), the proportion of wage-labour being substantially greater than that of family labour. The value of their output is as much as 10,000 rubles, while the number of wage-workers employed is ten and more per establishment. These large establishments, therefore, represent capitalist workshops. The census data consequently reveal the prevalence of purely capitalist laws and relations in the celebrated “handicraft” industry; they reveal the absolute superiority of the capitalist workshops, based on the co-operation of wage-workers, over the one-man workshops and small workshops in general—a superiority both in productivity of labour and in remuneration for labour, even of wage-workers.

4) In the case of a number of the industries the earnings of the small independent handicraftsmen prove to be no higher, and often even lower, than the earnings of wage-workers in the same industry. This difference would be even greater if to the wage-workers’ earnings were added the value of the board received by some of them.

We have dealt with this last conclusion separately because the first three concern phenomena that are universal and inevitable under the laws of commodity production, whereas the last does not contain phenomena that are everywhere inevitable. We accordingly formulate this concept as follows: because of lower labour productivity in small establishments and the defenceless position of their owners in the market (especially in the case of agriculturists), it is possible that the earnings of an independent handicraftsman may be lower than those of a wage worker—and the facts show that this very often is the case.

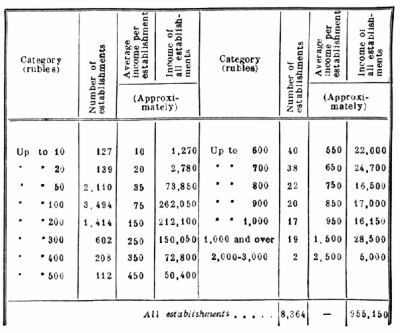

The validity of our calculations is beyond question, for we have taken a number of industries, not choosing them at random, but taking all those where the tables allowed us to deal with the large establishments separately; we have not taken individual establishments, but all those of the same kind, and in every case compared with them several large establishments in different uyezds. But it would be desirable to express the phenomena described in a more general and more precise form. Fortunately, the Sketch contains material that enables us to satisfy this desire in part. This is the material on the division of establishments according to net income. In the case of certain industries, the Sketch indicates how many establishments have a net income of up to 50, 100, 200 rubles, etc. It is these data that we have combined. We find that there are data available for 28 industries,[8] embracing 8,364 establishments, or 93.2% of the total number (8,991). In all, in these 28 industries there are 8,377 establishments (income figures are not given for 13 establishments), with 14,135 family and 4,625 wage-workers, or 18,760 in all, which constitutes 93.9% of the total number of workers. Naturally, from these data covering 93% of the handicraftsmen we are fully entitled to draw conclusions regarding all of them, for there are no grounds for assuming that the remaining 7% differ from these 93%. Before presenting our summary, it is necessary to make the following remarks:

1) In thus classifying the material, the compilers of the Sketch have not always strictly adhered to uniform and identical headings for the groups. For example, they have “up to 100 rubles,” “less than 100 rubles,” and sometimes even “100 rubles each.” The top and bottom limits of the category are not always indicated, that is, sometimes the classification begins with the category “up to 100 rubles,” sometimes with that of “up to 50 rubles,” “up to 10 rubles,” and so on; sometimes the classification ends with the category “1,000 rubles and over,” sometimes the categories “2,000 to 3,000 rubles” and others are introduced. None of these inaccuracies is of any serious importance. We have unified all the categories contained in the Sketch (there are fifteen of them: up to 10, up to 20, up to 50, up to 100, up to 200, up to 300, up to 400, up to 500, up to 600, up to 700, up to 800, up to 900, up to 1,000, 1,000 and over, and 2,000 to 3,000 rubles), and we have eliminated all minor inaccuracies and misunderstandings by assigning them to one or another of these categories.

2) The Sketch only indicates the number of establishments in certain income categories, but does not indicate the income of all the establishments in each category. Yet it is these latter figures that we need most. We have therefore assumed that the aggregate income of the establishments in any category is determined with sufficient accuracy by multiplying the number of establishments by the average income, that is, by the arithmetical mean of the maximum and minimum of the given category (for example, 150 rubles in the case of the 100 to 200 ruble category, etc.). Only in the case of the lowest two categories (up to 10 rubles and up to 20 rubles) have the maximum incomes (10 rubles and 20 rubles respectively) been taken instead of the averages. Verification has shown that this method (one generally permissible in statistical calculations) yields results that approximate very closely to reality. For instance, the aggregate net income of the handicraft families in these 28 industries, according to the Sketch, amounts to 951,653 rubles, while according to our approximate figures, based on the income categories, it amounts to 955,150 rubles, an excess of 3,497 rubles = 0.36%. Consequently, the difference or error is less than 4 kopeks in 10 rubles.

3) From our summary we learn the average income per family (in each category), but not per family worker. To determine the latter, another approximate calculation had to be made. Knowing the division of families according to the number of family workers (and separately—according to the number of wage-workers employed), we assumed that the lower the income of a family, the smaller its size (i.e., the smaller the number of family workers per establishment) and the fewer the establishments employing wage-workers. On the contrary, the higher the income per family, the larger the number of establishments employing wage-workers and the larger the family, that is, the number of family workers per establishment is larger. Obviously, this assumption is the most favourable for anyone who might want to contest our conclusions. In other words, whatever other assumption was made, it would only help to reinforce our conclusions.

We now give a summary showing the division of the handicraftsmen according to the income of their establishments.

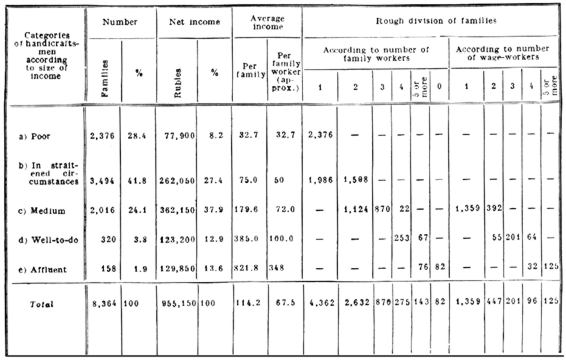

These data are too detailed and have therefore to be combined under simpler and clearer headings. Let us take five income categories of handicraftsmen: a) poor, with incomes of up to 50 rubles per family; b) in straitened circumstances, with incomes of 50 to 100 rubles per family; c) medium, with incomes of 100 to 300 rubles per family; d) well-to-do, with incomes of 300 to 500 rubles per family, and e) affluent, with incomes of over 500 rubles per family.

According to the data showing the incomes of establishments we shall add to these categories a rough division of establishments according to the number of family and wage workers they employ.[9] We get the following table (see p. 417).

These data lead to very interesting conclusions, which we shall now enumerate, taking the handicraftsmen category by category:

a) Over one-fourth of the families (28.4%) come under the category of poor, with an average income of about 33 rubles per family. Let us assume that this is the income of only one family worker, that all in this category are one man producers. In any case the earnings of these handicrafts men are considerably lower than the average earnings of wage-workers employed by handicraftsmen (45.85 rubles). If the majority of these one-man producers belong to the lower (3rd) sub-group, that is, work for buyers-up, this means that the “masters” pay those who work at home less than wage-workers employed in the workshop. Even if we assume that the working period of this category is the shortest, their earnings are nevertheless at the poverty level.

b) Over two-fifths of the total number of handicraftsmen (41.8%) belong to the group of families in straitened circumstances, who have an average income of 75 rubles per family. Not all of these are one-man establishments (the previous category was assumed to consist solely of one-man producers): about half the families have two family workers each, and hence the average earnings per family worker are only about 50 rubles, i.e., not more, or even less, than the earnings of a wage-worker employed by a handicraftsman (apart from wages, amounting to 45.85 rubles, part of the wage-workers also receive their board) Thus, judged by their earnings, seven-tenths of the total number of handicraftsmen are on a par with, and some even at a lower level than, the wage-workers employed by handicraftsmen. Astonishing as this conclusion is, it fully conforms to the facts quoted above on the superiority of large establishments over small. The low income level of these handicraftsmen can be judged by the fact that the average wage of an agricultural labourer employed by the year in Perm Gubernia is 50 rubles, in addition to board.[10] Consequently, the standard of living of seven-tenths of the “independent” handicraftsmen is no higher than that of agricultural labourers!

The Narodniks, of course, will say that these earnings are only supplementary to agriculture. But in the first place, has it not been established long ago that only a minority of the peasants are able to derive enough from agriculture to maintain their families, after land redemption payments, rent and farm expenses are deducted? And please note that we are comparing the handicraftsman’s earnings with the wages of a farm labourer who receives his board from his master. Secondly, seven-tenths of the total number of handicraftsmen must also include non-agriculturists. Thirdly, even if it turns out that agriculture covers the maintenance of the agriculturist handicraftsmen of these categories, the drastic effect of the tie with the land in reducing earnings still remains beyond all doubt.

Another comparison: in Krasnoufimsk Uyezd, the average earnings of a wage-worker employed by a handicraftsman are 33.2 rubles (p. 149 of the tables), while the average earnings of a person employed at “his own” works, that is, of an ironworker from among the former professional[13] peasants, are estimated by the Zemstvo statisticians at 78.7 rubles (Material for a Statistical Survey of Perm Gubernia. Krasnoufimsk Uyezd. Zavodsk District, Kazan, 1894), or over twice as much. And it is a generally known fact that the wages of ironworkers from among the former possessional peasants are always lower than wages of “free” workers in the factories. One can, therefore, see that reduced consumption, a miserable standard of living, is the price paid for the celebrated “independence” of the Russian handicraftsman “based on an organic tie between industry and agriculture”!

c) In the category of “medium” handicraftsmen we have included families with incomes of 100 to 300 rubles, or an average of about 180 rubles per family. They constitute almost one-fourth of the total number (24.1%). Absolutely, their income is very, very low: counting two-and-a-half family workers per establishment, it amounts to about 72 rubles per family worker—a very inadequate sum, and one which no factory worker would envy. Compared, however, with the incomes of the mass of handicraftsmen this sum is fairly high! It appears that even this meagre “sufficiency” is only secured at the expense of others: the majority of the handicraftsmen in this category employ wage-workers (roughly about 85% of the masters employ wage-labourers, and the average for the 2,016 establishments is over one wage-worker per establishment). Hence, in order to fight their way out of the mass of poverty-stricken handicrafts men, this category, under the existing commodity-capitalist relations, have to win a “sufficiency” for themselves from others, have to engage in economic struggle, to squeeze out the mass of the small producers still further and become petty bourgeois. Either poverty and the lowering of their standard of living to the nec plus ultra, or (for a minority ) the building-up of their (absolutely very meagre) welfare at the expense of others—such is the dilemma with which commodity production confronts the small producer. Such is the language of facts.

d) The category of well-to-do handicraftsmen embraces only 3.8% of the families, those with an average income of about 385 rubles, or about 100 rubles per family worker (assuming that under this heading come masters with 4 or 5 family workers per establishment). Such an income, about double the earnings of a wage-worker, is already based on a considerable employment of wage-labour: all the establishments in this category employ an average of about 3 wage-workers per establishment.

e) The affluent handicraftsmen, those with an average income of 820 rubles per family, constitute only 1.9% of the total. This category partly includes establishments with 5 family workers, and partly establishments with no family workers at all, that is, those based exclusively on wage-labour. On an average, this amounts to about 350 rubles of income per family worker. The high incomes of these “handicraftsmen” accrue from the large number of wage-workers employed, averaging about 10 persons per establishment.[11] These are already small manufacturers, owners of capitalist workshops, and to include them among the “handicraftsmen,” together with the one-man establishments, rural artisans and even domestic producers who work for manufacturers (and sometimes, as we shall see below, for these same affluent handicraftsmen!) only testifies, as we have already remarked, to the utter vagueness and haziness of the term “handicraft.”

In concluding our examination of the census data on handicraftsmen’s incomes we must make the following remark. It might be said that the concentration of incomes in the handicraft industries is not very high: 5.7% of the establishments account for 26.5% of the total income, and 29.8% for 64.4%. Our reply to this is that, firstly, even this degree of concentration shows how totally unsuitable and unscientific are sweeping arguments about “handicraftsmen,” and “average” figures relating to them. Secondly, we should not lose sight of the fact that these data do not include buyers-up, with the result that the income division is highly inaccurate. We have seen that 2,346 families and 5,628 workers work for buyers-up (third sub-group); consequently, here it is the buyers-up who get the principal income. Their separation from the mass of the producers is absolutely artificial and entirely unwarranted. Just as it would be wrong to describe the economic relations in large-scale factory industry without mentioning the size of the manufacturers’ incomes, so is it wrong to describe the economics of “handicraft” industry without mentioning the incomes of the buyers-up—incomes obtained from the same industry in which handicraftsmen are also engaged, and constituting part of the value of goods produced by handicraftsmen. We are therefore entitled, in fact we are obliged, to conclude that the actual distribution of incomes in handicraft industry is far more uneven than was shown above, for the categories which include the largest industrialists of all have been omitted.

[1] It goes without saying that only handicraftsmen in the same sub-group can be compared, and that a commodity producer cannot be compared with an artisan or a handicraftsman who works for a buyer-up. —Lenin

[2] But these are by no means the largest establishments. From the division of establishments according to number of wage-workers (p. 113) it may be calculated that in three establishments there are 163 wage-workers, or an average of 54 per establishment. Yet these are also regarded as “handicraft establishments” and are added together with the one-man workshops (of which there are no less than 460 in the industry) to obtain general “average”! —Lenin

[3] “In one of the establishments” the introduction of a wool-carding machine was mentioned (p. 119). —Lenin

[4] There is apparently a misprint or error in the table on p. 158: in Irbit Uyezd the net income is more than the 9,827 rubles shown in the total. We had to change this table according to the data in the tables appended to the Sketch. —Lenin

[5] Cf. Handicraft Industries, pp. 46-47, as well as the description of the industry given in the Sketch, p. 162, et. seq. It is most typical that “these employers were once real handicraftsmen and that is why they have always been fond of giving themselves that name.” —Lenin

[6] It may be seen from the Sketch that in the pitch and tar industry both the primitive method of distilling pitch in pits and the more perfected cauldron, and even cylindrical boiler, methods are employed (p. 195). The household census furnished material showing the distribution of these different methods, but it was not utilised, the large establishments not being treated separately. —Lenin

[7] Cf. vehicle building, p. 308 of the text and pp. 11 and 12 of the tables; chest making, p. 335; tailoring, p. 344, etc. —Lenin

[8] These data are also available for the lace-, lock- and accordion making industries, but we omit them, as they do not record establishments according to the number of family workers. —Lenin

[9] The 8,377 establishments in the 28 industries are divided according to the number of family and wage-workers as follows: no family workers—95 establishments; 1 worker—4,362; 2 workers—2,632; 3 workers—870; 4 workers—275; 5 workers and over—143. The establishments employing wage-workers number 2,228, and are divided as follows: 1 wage-worker—1,359; 2 workers—447; 3 workers—201; 4 workers—96; 5 workers and more—125. The wage workers total 4,625, and their aggregate wages total 212,096 rubles (45.85 rubles per worker). —Lenin

[10] The cost of board is 45 rubles per annum, according to the figures—average for 10 years (188l-91)—of the Department of Agriculture. (See S. A. Korolenko, Hired Labour, etc.) —Lenin

[11] Of the 2,228 establishments employing wage-workers in these 28 industries, 46 employ 10 wage-workers or more—a total of 887, or an average of 19.2 wage-workers per establishment. —Lenin

[12] Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. I, Moscow, 1958, p. 390.

[13] By a decree of Peter I issued in 1721 merchant factory owners were given the right to purchase peasants for work in their factories. The feudal workers attached to such enterprises under the possessional right were called “possessional peasants.”

| | |

| | | | | | |