Page 20 of Notebook “ξ” (“Xi”)

Reduced

B. L. Baron von Mackay, China, the Middle Republic. Its Problems and Prospects, Berlin, 1914. ((264 pp. + supplements.))

|

A scoundrel, reactionary, blockhead and swine; has lifted from a dozen books a heap of slanders against “radical democrats” (the Kuomintang and its leader Sun Yat-sen). Scientific value nil. Pp. ?? Supplement V. Kuomintang leaflet = naïve, democratic republicanism ((the scound- rel of an author heaps abuse on it)). [“An Analysis of the Advantages of the Republic”.] |

|||

| N.B. | |||

|

Source References: James Cantlie and Sheridan Jones, Sun Yat-sen and the Awakening of China, London, 1913. Vosberg-Rekow, The Revolution in China, Berlin, 1912 Joseph Schön, Russia’s Aims in China, Vienna, 1900. M. v. Brandt, East Asian Questions, Berlin, 1897. Wilhelm Schüler, Outline of the Recent History of China, Berlin, 1913. |

||

The chapter “International Political Troubles and Conflicts” (Chapter 13) contains a brief account of the plunder of China by Russia (Mongolia) [the secret Urga protocol, 1912], by Russia + Japan (Manchuria. The secret treaty of Russia and Japan, July 8, 1912), by Great Britain (Tibet), by Germany (Kiao-chow[1]), etc.

|

pp. 222-24: written after the Japanese ultimatum to Germany (August or September 1914)—gross abuse of Great Britain for her “policy, dictated solely by the interests of the shopkeepers and money-bags” (223), her crime against European civilisation, etc., etc. For his part, the author favours “extending the German power position in China” (228).... |

|||||

| !!! | |||||

|

Germany’s share in Chinese trade=4.2 per cent, but factually (he says) (N.B.) more than 7 per cent— and up to 25 per cent (!!?) if the total German trade turnover is taken into account. Britain’s share in Chinese trade=50 per cent, but factually 21 per cent (p. 232). |

|

...“just as ‘international’ capital becomes ever more national under the impact of modern imperialist power tendencies, so the mechanism of what we call world economy has to become more and more respon- sive to the laws of the national economies of the Great Powers” (235). |

||

| N.B. |

((Chapter 14: “Germany’s Mission”.))

|

Britain and the U.S.A. “last year alone raised 18 million marks to found new higher educational establishments in Shantung, Hankow and Hong Kong” (236)—compared with this sum, everything Germany allocated during the same period “appears minute”. Where does the money come from? The chief source is the big British and American capitalists’ commer- cial and industrial enterprises in China!! |

N.B. | ||

|

Britain has “hundreds” of officials in “her maritime customs service” who know the Chinese language!! (“trained officers”)—pioneers (239).... |

!! |

Belgium and her commercial interests in China (243): Société d’Etudes des Chemins de fer en Chine,—its concessions on two railways in China.

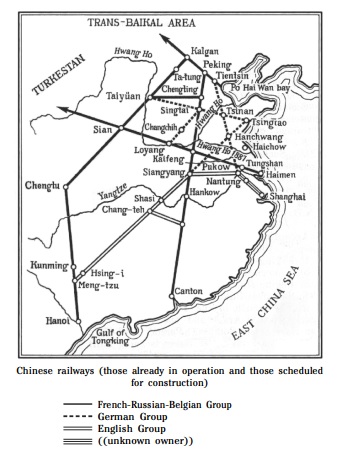

p. 245—a map of railways in operation and scheduled for construction in China, in three groups

| N.B. | 1) German— — —(medium-sized) |

| 2) British— — —(smallest) | |

| 3) Russo-Franco-Belgian— — —(largest) |

According to Hennig (World Communication Routes, Leipzig, 1909), the following lines already exist;

1) Peking-Tientsin (and continuation to Dalny)

2) Kiao-chow—Tsinanfu[2]

3) Peking-Hankow

4) Shanghai-Pukow

...“The mouth of the Yangtze is Great Britain’s East-Asian Shatt-al-Arah, and the Yangtze sphere of interest her East-Asian Southern Persia” (246-47)....

|

The Tientsin-Pukow railway is being built jointly by the British and Germans (247). Great Britain has 1,900 km. of railway conces- sions in China (247).... |

N.B. N.B. |

|

Germany has 700 km. of railway concessions in China (248).... |

Mackay p. 245

In the great work of irrigation and land reclamation in China, German technique is supreme (254-55 et seq.)....

|

The Chinese ought not to sympathise with the “radical democracy of the New World”, nor with Anglo-Saxon Constitutionalism with its “faded monarchism”, but with monarchical Germany (257) |

!! |

|

Then follows a long, dreary and stupid eulogy of German culture.... |

!!! |

End

[1] Present name Tsingtao.—Ed.

[2] Present name Tsinan—Ed.

| | |

| | | | | | | ||||||