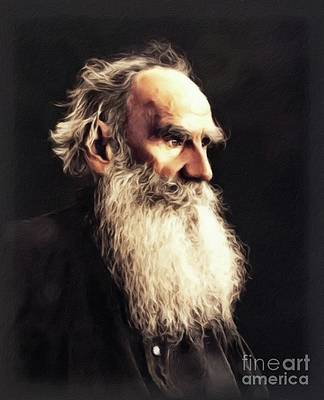

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1862

Source: From RevoltLib.com

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

We have no beginners. The children of the youngest class read, write, and solve problems in the first three rules of arithmetic, and repeat sacred history, so that our order of exercises is arranged according to the following roster:

Before I speak of the methods of instruction, I must give a short description of the Yasnaya Polyana school and its present condition.

Yasnaya Polyana, or Fairfield, is the name of the count's estate a few miles out from the city of Tula. It is also the name of a journal of education published at his own expense. A complete file of this journal is in the library of Cornell University, the gift of the late Mr. Eugene Schuyler, to whom Count Tolstoy presented it.

Like every living body the school not only changes every year, day, and hour, but also has been subjected to temporary crises, misfortunes, ailments, and ill chances.

The Yasno-Polyanskaya school passed through one such painful crisis this very summer. There were many reasons for this: in the first place, as is always the case in the summer, all the best scholars were away; only occasionally we would meet them in the fields at their work or tending the cattle. In the second place, there were some new teachers present, and new influences began to be brought upon it. In the third place, each day teachers from other places, taking advantage of their summer vacation, came to visit the school. And nothing is more demoralizing to the regular conduct of a school than to have visitors, even though the visitor be a teacher himself.

We have four instructors. Two are veterans, having already taught two years in the school; they are accustomed to the pupils, to their work, and to the freedom and apparent lawlessness of the school.

Two of the teachers are new; both of them are recent graduates and lovers of outward propriety, of rules and bells and regulations and programs and the like, and are not wonted to the life of the school, as the first two are. What to the first seems reasonable, necessary, impossible to be otherwise, like the features on the face of a beloved though homely child, who has grown up under your very eyes, sometimes seems to the new teachers sheer disorder.

The school is established in a two-storied stone house. Two rooms are devoted to the school; the library has one, the teachers have two. On the porch, under the eaves, hangs the little bell with a cord tied to its tongue; in the entry down-stairs are bars and other gymnastic apparatus; in the upper entry is a workbench.

The stairs and entries are generally tracked over with snow or mud; there also hangs the roster.

The order of exercises is as follows:

At eight o'clock, the resident teacher, who is a lover of outward order, and is the director of the school, sends one of the lads who almost always spends the night with him to ring the bell.

In the village the people get up by lamplight. Already in the schoolhouse window lights have long been visible, and within half an hour after the bell-ringing, whether it be misty or rainy, or under the slanting rays of the autumn sun, there will be seen crossing the rolling country the village is separated from the school by a ravine dark little figures in twos or threes, or separately. The sense of gregariousness has long ago disappeared from among the pupils. There is now no longer need of any one waiting and crying:

"Hey, boys! to school!"

The boy has already learned that school uchilishcke is a neuter gender; he knows many other things besides; and curiously enough in consequence of this he does not need the support of a crowd any more. When it is time for him to go he goes.

Every day, it seems to me, they grow more and more independent and individual, and their characters more sharply defined. I have almost never seen them playing on the way, unless in the case of some of the smaller pupils, or of the newcomers who had begun in other schools.

They bring nothing with them no books and no copy-books. They are not required to study their lessons at home. Not only do they bring nothing in their hands, but nothing in their heads either. The scholar is not obliged to remember to-day anything he may have learned the evening before. The thought about his approaching lesson does not disturb him. He brings only himself, his receptive nature, and the conviction that school to-day will be just as jolly as it was the day before.

He does not think about his class until his class begins. No one is ever held to account for being tardy, and hence they are not tardy, unless indeed one of the older ones may be occasionally detained by his parents on account of some work. And then this big lad comes running to school at breakneck speed and all out of breath.

If it happens that the teacher has not yet come, they gather around the entrance, pounding their heels upon the steps, or sliding on the icy path, or some of them wait in the school-rooms.

If it be cold they spend their time while waiting for the teacher in reading, writing, or romping.

The girls do not mingle with the boys. When the boys have any scheme which they wish to propose to the girls, they never select any particular girl, but always address the whole crowd: -

"Hey, girls, why are n't you sliding?" or, "See, the girls are freezing," or "Now, girls, all of you chase me!"

Only one of the little girls, a ten-year-old domestic peasant[1] of great many-sided talents, perhaps ventures to leave the herd of damsels. And with her the boys comport themselves as with an equal as with a boy, only showing a delicate shade of politeness, modesty, and self-restraint.