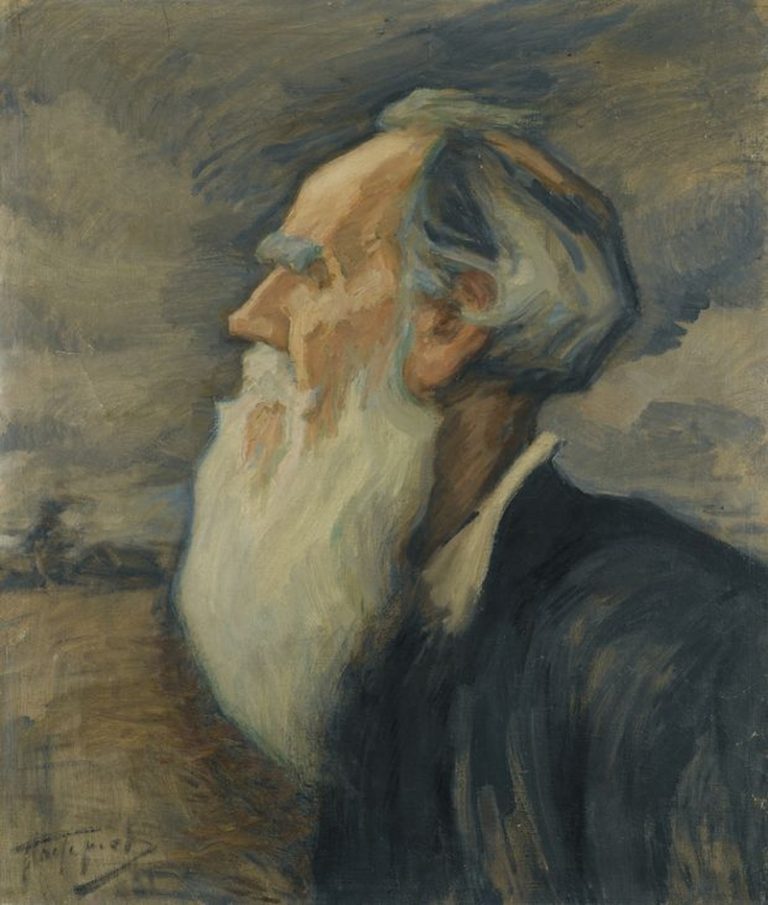

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1862

Source: From RevoltLib.com

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

I had the intention in this first lesson of explaining wherein Russia differs from other countries, her borders, the characteristic feature of its government; to tell who was the reigning monarch at this time, and how and when the Emperor mounted the throne.

TEACHER. Where do we live? in what land?

A PUPIL. At Yasnaya Polyana.

SECOND PUPIL. In the country.

TEACHER. No; in what land are both Yasnaya Polyana and the Government of Tula?

PUPIL. The Government of Tula is seventeen versts from us. Where is it? Why the Government is the government.

TEACHER. No; Tula is a government capital, but a government is another thing. [46] Now what land is it?

PUPIL (who had been in the geography class). The land [47] is round like a ball.

By means of such questions as "What is the land where a German, whom they knew, lived," and "Where would you come to if you should keep going in one direction," the pupils were at last brought to answer that they lived in Russia. Some, however, answered the question, "Where would you come out if you kept traveling straight ahead?" by saying, "We should not come out anywhere." Others said that "you would come to the end of the world."

TEACHER (repeating one pupil's reply). You said that you would reach other countries. Where does Russia end, and where do the other countries begin?

PUPIL. Where you find the Germans.

TEACHER. Now, then, if you should find Gustaf Ivanovitch and Karl Feodorovitch in Tula, would you say that this was the land of the Germans, and therefore it must be another country?

PUPIL. No; it 's where you find a whole lot of Germans.

TEACHER. Not necessarily; for in Russia there is a land where there are a whole lot of Germans. Johann Fomitch here comes from there, and yet this land is Russia. How is that?

Silence.

TEACHER. It is because they obey the same laws as the Russians.

PUPIL. How do they have the same law? The Germans do not attend our church, and they eat meat in Lent!

TEACHER. Not the same law, perhaps, but they obey the same Czar.

PUPIL (the skeptic Semka). Strange! Why do they have a different law and yet obey our Czar?

The teacher feels the necessity of explaining what a law is, and he asks what it means to obey a law, to be under one law.

A PUPIL (the self-confident little domestic, hastily and timidly). To obey a law means to get married!

The pupils look questioningly at the teacher: Is that right?

The teacher begins to explain that a law means that if any one steals or kills, then he is shut up in prison and is punished.

THE SKEPTIC SEMKA. But don't the Germans have this?

TEACHER. Law also means this, that we have nobles, peasants, merchants, clergy. (The word clergy dukhovienstvo gave rise to perplexity.)

THE SKEPTIC SEMKA. And don't they have them there?

TEACHER. They have them in some countries, in others they don't. We have the Russian Czar, and in German countries there is another the German Czar.

This answer satisfied all the pupils, even the skeptic Semka.

The teacher, seeing the necessity of explaining class distinctions, asks what classes they know.

The pupils try to enumerate them the nobility, the peasantry, popes or priests, soldiers.

"Any others?" asks the teacher.

"Domestics, koziuki,[48] samovar-makers."[49]

The teacher asks the distinctions between these different classes.

THE PUPILS. The peasants plow; domestic servants serve; merchants trade; samovarshchiki make samovars; popes perform masses; nobles do not do anything.

The teacher explains the actual differences between the classes, but finds it perfectly idle to make them see the necessity of soldiers when there is no war, that it is merely to serve as a security against the dissolution of the Empire, and the part taken by the nobles in the civil service. The teacher tries in the same way to explain the difference geographically between Russia and other countries; he says that the whole world is divided into various realms. The Russians, the French, the Germans, divided the whole earth, and said to themselves: "Up to these limits is ours, up to those is yours;" and thus Russia and all other nations have their boundaries.

TEACHER. Do you understand what a boundary is? Give me an example of one.

A PUPIL (an intelligent lad). Here, just beyond the Turkin Hill, is a boundary.

This boundary is a stone post standing on the road between Tula and Yasnaya Polyana, indicating the beginning of the Tula District.

All the pupils acquiesce in this definition.

The teacher sees the necessity of pointing out the boundaries on some well-known place. He draws the plan of the two rooms, and indicates the line that separates them; then he brings the plan of the village, and the scholars themselves point out several well-known boundaries. The teacher explains that is, he thinks that he explains that just as Yasnaya Polyana has its boundaries, so Russia has its boundaries. He flatters himself with the hope that they have all understood him; but when he asks, "How is it possible to know how far it is from our place to the Russian boundary?" then the pupils, in no little perplexity, reply that it is very easy; all it requires is to take a yardstick and measure to the Russian boundary.

TEACHER. In which direction?

PUPILS. Go straight from here to the boundary, and put down how far you have gone.

Again we made use of sketches, plans, and maps. Here came up the need of giving them an idea of the meaning of a "scale." The teacher proposed to draw the plan of the village, disposed in streets. We began the sketch on the blackboard, but we could not get the whole village in because the scale was too large. We rubbed it out, and began anew on a slate. The scale, the plan, the boundaries, gradually became clear. The teacher repeated all that he had said, and then asked what Russia was, and where it ended.

PUPIL. It's the land in which we live, and where the Germans and Tartars live.

ANOTHER PUPIL. The land that is under the Russian Czar.

TEACHER. Where is the end of it?

A GIRL. Where you find the heathen[50] Germans.

TEACHER. The Germans are not heathen. The Germans also believe in Christ. (Here he gives an explanation of religion and faiths.)

PUPIL (with alacrity, evidently taking delight in his good memory}. In Russia there are laws, Whoever kills gets put in prison; and there are all sorts of people, clergymen, soldiers, and nobles.

SEMKA. Who supports the soldiers?

TEACHER. The Czar. But then they collect the money from everybody, because everybody is benefited by their serving.

The teacher furthermore explains what the budget is, and finally, with only tolerable success, we get them to repeat what has been said about boundaries.

The lesson lasts two hours. The teacher is persuaded that the children have retained a good deal of what has been said, and the succeeding lessons are carried on in the same style, but in the sequel he is forced to the conclusion that these methods are unsatisfactory, and that all that he has done is perfect rubbish.

Involuntarily I fell into the usual error of the Socratic method carried on in the German Anschauungsunterricht to the last degree of monstrosity. In these lessons I gave no new ideas to the pupils, though I fancied that I was doing so. And only by my moral influence did I compel the children to answer as I wished them to do. Raseya, "Russia," Russkoi, "Russian," remained the same unconscious symbols of mine, ours, something vague and indeterminate. Zakon, "law," remains to them an incomprehensible word.

I made these experiments six months ago, and at first was thoroughly satisfied and proud of them. Those to whom I read them said that it was thoroughly good and interesting; but after three weeks, during which I could not myself look after the school, I proposed to carry out what I had begun, and I became convinced that all that had gone before was nonsense and self-deception. Not one pupil was able to describe a frontier, Russia, a law, or the boundaries of the Krapivensky District; all they had learned they had forgotten; but at the same time they knew it all in their own way. I was convinced of my mistake, but I could not make out whether my mistake consisted in a bad method of instruction, or in the very idea of it. Maybe there is no possibility before a certain period of general development, and without the* help of newspapers and travel, to awaken in a child an interest in history and geography. Maybe we shall find the method by means of which this can be done, and I keep trying and experimenting. One thing only I know, that this method will never be attained by so-called history and geography; that is, in the teaching by books, for this kills, and does not awaken, this interest.