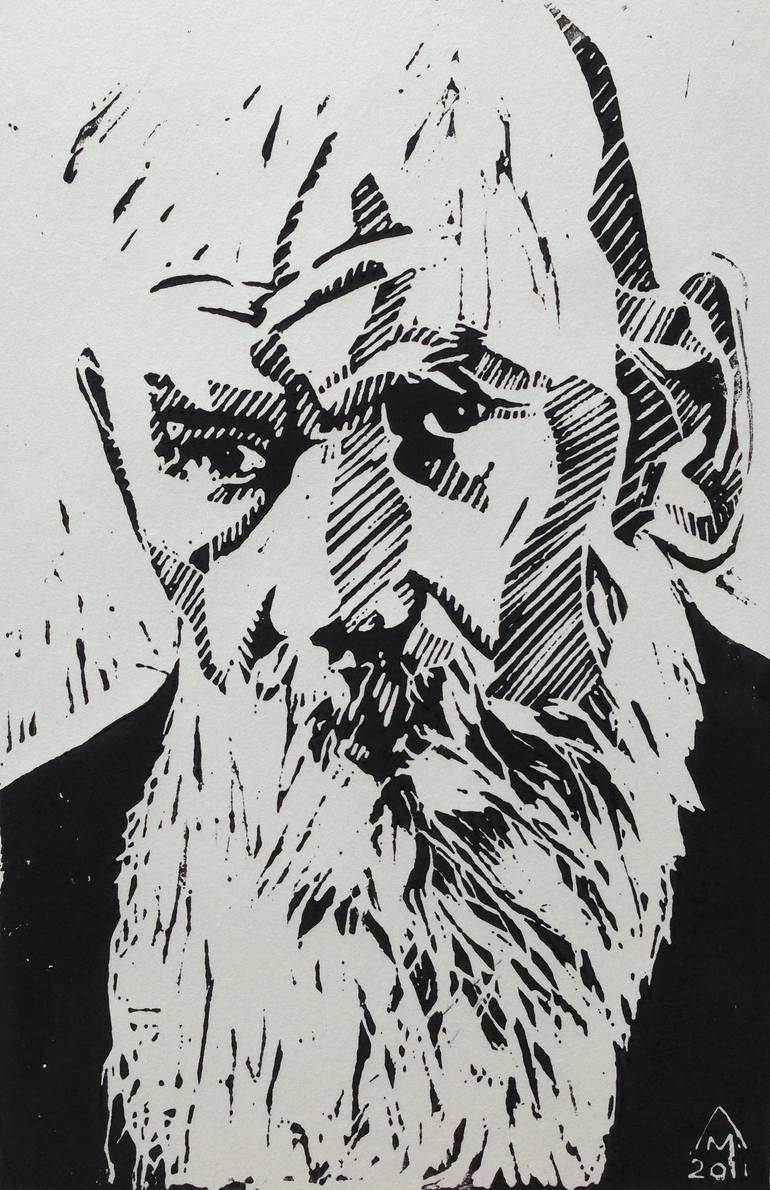

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1862

Source: From RevoltLib.com

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

As they are subjected to laws that are simply derived from their own nature, the scholars do not rebel or grumble; if they were subjected to our old system of interference, they would have no faith in the legality of our ringing bells, regulations, and ordinances.

How many times when children were fighting, have I chanced to see the teacher hasten to separate them; and the disparted foes would glare at each other, and even in the presence of a stern teacher would not fail to look even more fiercely than before, or even fall to blows; how many times every day do I see some Kiriushka set his teeth together, and fly at Taraska, and pull his hair, and throw him to the ground, and apparently try to maim his enemy or to annihilate him; and then, in a moment's time, this same Taraska would be laughing at Kiriushka, for always one manages to turn the tables on the other, and then in the course of five minutes they would have made friends and gone off to sit down together.

Not long ago, between classes, two lads grappled in a corner. One was a remarkable mathematician nine years old, a member of the second class; the other a shingled dvorovui,[4] clever but quick-tempered, very small in stature, a black-eyed lad named Kuiska.

Kuiska had caught the mathematician's long hair, and was holding him with his head against the wall. The mathematician was vainly clutching at Kuiska's shorn bristles. Kuiska's black eyes were full of triumph. The mathematician could barely refrain from tears, and he cried, "Well! well! what! what!" but he was evidently having a hard time of it, and only his pride kept his courage up. This had been going on for some time, and I was undecided what to do.

"A fight! a fight!" cried the boys, and they crowded round the corner. The little ones laughed; but the big boys, though they did not attempt to separate the contestants, looked at them rather seriously, and their looks and silence did not fail to have an effect upon Kuiska. He was conscious that he was doing wrong, and a smile began gradually to creep over his face, and by degrees he let go of the mathematician's hair. The mathematician suddenly twitched himself away, and gave Kuiska such a push as to knock his head against the wall, and then, being entirely quit of him, he ran away.

Kuiska burst into tears, darted in pursuit of his enemy, and hit him with all his might and main on the shuba, but did not hurt him. The mathematician was going to pay him back, but at that instant various dissuasive voices were heard:

"See, he strikes a smaller boy!" cried the lookers-on; "off with you, Kuiska!"

And so the affair ended, as if it had not been at all, except, I may add, for the vague consciousness that each had of having fought disagreeably, because both had been hurt. And here I cannot refrain from calling attention to the sentiment of justice which prevailed in the crowd. How many times these affairs are settled in such a way that you cannot make out the principles on which the settlement is made, and yet satisfaction is given to both sides! How arbitrary and unjust in comparison with this are all "educational efforts" in such circumstances!

"You are both to blame! down on your knees!" says the disciplinarian; and the disciplinarian is wrong, because one is to blame, and this one is triumphant there on his knees chewing the cud of his not wholly evaporated passion, and the innocent is doubly punished.

Or, "You are to blame for doing such and such or such and such a thing, and you shall be punished," says the disciplinarian; and the one punished hates his enemy more than ever, because he has arrayed on his side despotic power, the fairness of which is beyond his comprehension.

Or, "Forgive him as God commands you, and be better than he," says the disciplinarian. You say to him, "Be better than he!" but all that he wants is to be stronger, and he does not comprehend, and cannot comprehend, the idea of being better.

Or, "You both are to blame; ask each other's pardon and kiss each other, children."

This is worse than anything, both on account of the insincerity of the kiss, and because the evil passion once calmed in this way is sure to burst forth again. But leave them alone, unless you are either father or mother, who would feel some pitiful sympathy with your children, and therefore have a certain right always, leave them alone, I say, and watch how everything explains itself and comes out all right as simply and naturally, and at the same time with just as much variety and complication as all the unconscious relations of life.

But perhaps the teachers who have not had experience of such disorder or free order, will think that without disciplinary interference this disorder may take on physically injurious consequences; that they will break each other's limbs or kill each other.

In the Yasnaya Polyana school last spring, there were only two cases of serious damage being done. One boy was pushed down from the steps, and cut his leg to the bone, the wound was healed in two weeks; the other had his cheek burned with blazing pitch, and he carried a scar for a fortnight.

Nothing ever happened, unless perhaps once a week some one cried, and that not from pain, but from vexation or shame. Of blows, bruises, bumps, except in the case of the two boys just mentioned, we cannot recall a single one during all the summer among thirty or forty pupils, though they were left entirely to their own guidance.