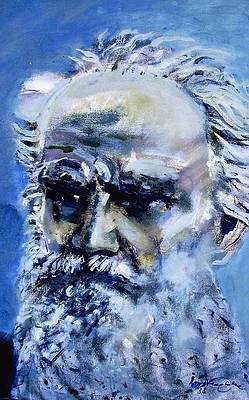

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1887

Source: Original Text from Gutenberg.org

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

It was late when the expedition, deploying in a broad column, entered the fortress with songs. The sun had set behind the snow-covered mountain crest, and was throwing its last rosy rays on the long delicate clouds which stretched across the bright pellucid western sky. The snow-capped mountains began to clothe themselves in purple mist; only their upper outlines were marked with extraordinary distinctness against the violet light of the sunset. The clear moon, which had long been up, began to shed its light through the dark blue sky. The green of the grass and of the trees changed to black, and grew wet with dew. The dark masses of the army, with gradually increasing tumult, advanced across the field; from different sides were heard the sounds of cymbals, drums, and merry songs. The leader of the sixth company sang out with full strength, and full of feeling and power the clear chest-notes of the tenor were borne afar through the translucent evening air.

*

(Rúbka L'ýesa.)

THE STORY OF A YUNKER'S[1] ADVENTURE.

I.

In midwinter, in the year 185-, a division of our batteries was engaged in an expedition on the Great Chetchen River. On the evening of Feb. 26, having been informed that the platoon which I commanded in the absence of its regular officer was detailed for the following day to help cut down the forest, and having that evening obtained and given the necessary directions, I betook myself to my tent earlier than usual; and as I had not got into the bad habit of warming it with burning coals, I threw myself, without undressing, down on my bed made of sticks, and, drawing my Circassian cap over my eyes, I rolled myself up in my shuba, and fell into that peculiarly deep and heavy sleep which one obtains at the moment of tumult and disquietude on the eve of a great peril. The anticipation of the morrow's action brought me to such a state.

At three o'clock in the morning, while it was still perfectly dark, my warm sheep-skin was pulled off* from me, and the red light of a candle was unpleasantly flashed upon my sleepy eyes.

"It's time to get up," said some one's voice. I shut my eyes involuntarily, wrapped my sheep-skin around me again, and dropped off into slumber.

"It's time to get up," repeated Dmitri relentlessly, shaking me by the shoulder. "The infantry are starting." I suddenly came to a sense of the reality of things, started up, and sprang to my feet.

Hastily swallowing a glass of tea, and taking a bath in ice-water, I crept out from my tent, and went to the park (where the guns were placed). It was dark, misty, and cold. The night fires, lighted here and there throughout the camp, lighted up the forms of drowsy soldiers scattered around them, and seemed to make the darkness deeper by their ruddy flickering flames. Near at hand one could hear monotonous, tranquil snoring; in the distance, movement, the babble of voices, and the jangle of arms, as the foot-soldiers got in readiness for the expedition. There was an odor of smoke, manure, wicks, and fog. The morning frost crept down my back, and my teeth chattered in spite of all my efforts to prevent it.

Only by the snorting and occasional stamping of horses could one make out in the impenetrable darkness where the harnessed limbers and caissons were drawn up, and, by the flashing points of the lintstocks, where the cannon were. With the words s Bógom,— God speed it,—the first gun moved off with a clang, followed by the rumbling caisson, and the platoon got under way.

We all took off our caps, and made the sign of the cross. Taking its place in the interval between the infantry, our platoon halted, and waited from four* o'clock until the muster of the whole force was made, and the commander came.

"There's one of our men missing, Nikolaï Petróvitch," said a black form coming to me. I recognized him by his voice only as the platoon-artillerist Maksímof.

"Who?"

"Velenchúk is missing. When we hitched up he was here, I saw him; but now he's gone."

As it was entirely unlikely that the column would move immediately, we resolved to send Corporal Antónof to find Velenchúk. Shortly after this, the sound of several horses riding by us in the darkness was heard; this was the commander and his suite. In a few moments the head of the column started and turned,—finally we also moved,—but Antónof and Velenchúk had not appeared. However, we had not gone a hundred paces when the two soldiers overtook us.

"Where was he?" I asked of Antónof.

"He was asleep in the park."

"What! he was drunk, wasn't he?"

"No, not at all."

"What made him go to sleep, then?"

"I don't know."

During three hours of darkness we slowly defiled in monotonous silence across uncultivated, snowless fields and low bushes which crackled under the wheels of the ordnance.

At last, after we had crossed a shallow but phenomenally rapid brook, a halt was called, and from the vanguard were heard desultory musket-shots. These sounds, as always, created the most extraordinary excitement in us all. The division had been almost* asleep; now the ranks became alive with conversation, repartees, and laughter. Some of the soldiers wrestled with their mates; others played hop, skip and jump; others chewed on their hard-tack, or, to pass away the time, engaged in drumming the different roll-calls. Meantime the fog slowly began to lift in the east, the dampness became more palpable, and the surrounding objects gradually made themselves manifest emerging from the darkness.

I already began to make out the green caissons and gun-carriages, the brass cannon wet with mist, the familiar forms of my soldiers whom I knew even to the least details, the sorrel horses, and the files of infantry, with their bright bayonets, their knapsacks, ramrods, and canteens on their backs.

We were quickly in motion again, and, after going a few hundred paces where there was no road, were shown the appointed place. On the right were seen the steep banks of a winding river and the high posts of a Tatar burying-ground. At the left and in front of us, through the fog, appeared the black belt. The platoon got under way with the limbers. The eighth company, which was protecting us, stacked their arms, and a battalion of soldiers with muskets and axes started for the forest.

Not five minutes had elapsed when on all sides piles of wood began to crackle and smoke; the soldiers swarmed about, fanning the fires with their hands and feet, lugging brush-wood and logs; and in the forest were heard the incessant strokes of a hundred axes and the crash of falling trees.

The artillery, with not a little spirit of rivalry with the infantry, heaped up their piles; and soon the fire was already so well under way that it was impossible* to get within a couple of paces of it. The dense black smoke arose through the icy branches, from which the water dropped hissing into the flames, as the soldiers heaped them upon the fire; and the glowing coals dropped down upon the dead white grass exposed by the heat. It was all mere boy's play to the soldiers; they dragged great logs, threw on the tall steppe grass, and fanned the fire more and more.

As I came near a bonfire to light a cigarette, Velenchúk, always officious, but, now that he had been found napping, showing himself more actively engaged about the fire than any one else, in an excess of zeal seized a coal with his naked hand from the very middle of the fire, tossed it from one palm to the other, two or three times, and flung it on the ground. "Light a match and give it to him," said another. "Bring a lintstock, fellows," said still a third.

When I at last lighted my cigarette without the aid of Velenchúk, who tried to bring another coal from the fire, he rubbed his burnt fingers on the back of his sheepskin coat, and, doubtless for the sake of exercising himself, seized a great plane-tree stump, and with a mighty swing flung it on the fire. When at last it seemed to him that he might rest, he went close to the fire, spread out his cloak, which he wore like a mantle fastened at the back by a single button, stretched his legs, folded his great black hands in his lap, and opening his mouth a little, closed his eyes.

"Alas![2] I forgot my pipe! What a shame, fellows!" he said after a short silence, and not addressing anybody in particular.

[1] Yunker (German Junker) is a noncommissioned officer belonging to the nobility. Count Tolstoy himself began his military service in the Caucasus as a Yunker.

[2] Ekh-ma.

*

II.

In Russia there are three predominating types of soldiers, which embrace the soldiers of all arms,—those of the Caucasus, of the line, the guards, the infantry, the cavalry, the artillery, and the others.

These three types, with many subdivisions and combinations, are as follows:—

(1) The obedient,

(2) The domineering or dictatorial, and

(3) The desperate.

The obedient are subdivided into the apathetic obedient and the energetic obedient.

The domineering are subdivided into the gruffly domineering and the diplomatically domineering.

The desperate are subdivided into the desperate jesters and the simply desperate.

The type more frequently encountered than the rest—the type most gentle, most sympathetic, and for the most part endowed with the Christian virtues of meekness, devotion, patience, and submission to the will of God—is that of the obedient.

The distinctive character of the apathetic obedient is a certain invincible indifference and disdain of all the turns of fortune which may overtake him.

The characteristic trait of the drunken obedient is a mild poetical tendency and sensitiveness.

The characteristic trait of the energetic obedient is his limitation in intellectual faculties, united with an endless assiduity and fervor.

*

The type of the domineering is to be found more especially in the higher spheres of the army: corporals, noncommissioned officers, sergeants and others. In the first division of the gruffly domineering are the high-born, the energetic, and especially the martial type, not excepting those who are stern in a lofty poetic way (to this category belonged Corporal Antónof, with whom I intend to make the reader acquainted).

The second division is composed of the diplomatically domineering, and this class has for some time been making rapid advances. The diplomatically domineering is always eloquent, knows how to read, goes about in a pink shirt, does not eat from the common kettle, often smokes cheap Muscat tobacco, considers himself immeasurably higher than the simple soldier, and is himself rarely as good a soldier as the gruffly domineering of the first class.

The type of the desperate is almost the same as that of the domineering, that is, it is good in the first division,—the desperate jesters, the characteristic features of whom are invariably jollity, a huge unconcern in regard to every thing, a wealth of nature and boldness.

The second division is in the same way detestable: the criminally desperate, who, however, it must be said for the honor of the Russian soldier, are very rarely met with, and, if they are met with, then they are quickly drummed out of comradeship with the true soldier. Atheism, and a certain audacity in crime, are the chief traits of this character.

Velenchúk came under the head of the energetically obedient. He was a Little Russian by birth, had been fifteen years in the service; and while he was not a fine-looking nor a very skillful soldier, still he was* simple-hearted, kind, and extraordinarily full of zeal, though for the most part misdirected zeal, and he was extraordinarily honest. I say extraordinarily honest, because the year before there had been an occurrence in which he had given a remarkable exhibition of this characteristic. You must know that almost every soldier has his own trade. The greater number are tailors and shoemakers. Velenchúk himself practiced the trade of tailoring; and, judging from the fact that Sergeant Mikháil Doroféïtch gave him his custom, it is safe to say that he had reached a famous degree of accomplishment. The year before, it happened that while in camp, Velenchúk took a fine cloak to make for Mikháil Doroféïtch. But that very night, after he had cut the cloth, and stitched on the trimmings, and put it under his pillow in his tent, a misfortune befell him: the cloth, which was worth seven rubles, disappeared during the night. Velenchúk with tears in his eyes, with pale quivering lips and with stifled lamentations, confessed the circumstance to the sergeant.

Mikháil Doroféïtch fell into a passion. In the first moment of his indignation he threatened the tailor; but afterwards, like a kindly man with plenty of means, he waved his hand, and did not exact from Velenchúk the value of the cloak. In spite of the fussy tailor's endeavors, and the tears that he shed while telling about his misfortune, the thief was not detected. Although strong suspicions were attached to a corruptly desperate soldier named Chernof, who slept in the same tent with him, still there was no decisive proof. The diplomatically dictatorial Mikháil Doroféïtch, as a man of means, having various arrangements with the inspector of arms and steward of the mess, the aristocrats of the battery, quickly forgot all* about the loss of this particular cloak. Velenchúk, on the contrary, did not forget his unhappiness. The soldiers declared that at this time they were apprehensive about him, lest he should make way with himself, or flee to the mountains, so heavily did his misfortune weigh upon him. He did not eat, he did not drink, was not able to work, and wept all the time. At the end of three days he appeared before Mikháil Doroféïtch, and without any color in his face, and with a trembling hand, drew out of his sleeve a piece of gold, and gave it to him.

"Faith,[3] and here's all that I have, Mikháil Doroféïtch; and this I got from Zhdánof," he said, beginning to sob again. "I will give you two more rubles, truly I will, when I have earned them. He (who the he was, Velenchúk himself did not know) made me seem like a rascal in your eyes. He, the beastly viper, stole from a brother soldier his hard earnings; and here I have been in the service fifteen years." ...

To the honor of Mikháil Doroféïtch, it must be said that he did not require of Velenchúk the last two rubles, though Velenchúk brought them to him at the end of two months.

[3] yéï Bogu.

*

III.

Five other soldiers of my platoon besides Velenchúk were warming themselves around the bonfire.

In the best place, away from the wind, on a cask, sat the platoon artillerist[4] Maksímof, smoking his pipe. In the posture, the gaze, and all the motions of this man it could be seen that he was accustomed to command, and was conscious of his own worth, even if nothing were said about the cask whereon he sat, which during the halt seemed to become the emblem of power, or the nankeen short-coat which he wore.

When I approached, he turned his head round toward me; but his eyes remained fixed upon the fire, and only after some time did they follow the direction of his face, and rest upon me. Maksímof came from a semi-noble family.[5] He had property, and in the school brigade he obtained rank, and acquired some learning. According to the reports of the soldiers, he was fearfully rich and fearfully learned.

I remember how one time, when they were making practical experiments with the quadrant, he explained, to the soldiers gathered around him, that the motions of the spirit level arise from the same causes as those of the atmospheric quicksilver. At bottom Maksímof was far from stupid, and knew his business admirably; but he had the bad habit of speaking, sometimes on* purpose, in such a way that it was impossible to understand him, and I think he did not understand his own words. He had an especial fondness for the words "arises" and "to proceed;" and whenever he said "it arises," or "now let us proceed," then I knew in advance that I should not understand what would follow. The soldiers, on the contrary, as I had a chance to observe, enjoyed hearing his "arises," and suspected it of containing deep meaning, though, like myself, they could not understand his words. But this incomprehensibility they ascribed to his depth, and they worshiped Feódor Maksímuitch accordingly. In a word, Maksímof was diplomatically dictatorial.

The second soldier near the fire, engaged in drawing on his sinewy red legs a fresh pair of stockings, was Antónof, the same bombardier Antónof who as early as 1837, together with two others stationed by one gun without shelter, was returning the shot of the enemy, and with two bullets in his thigh continued still to serve his gun and load it.

"He would have been artillerist long before, had it not been for his character," said the soldiers; and it was true that his character was odd. When he was sober, there was no man more calm, more peaceful, more correct in his deportment; when he was drunk he became an entirely different man. Not recognizing authority, he became quarrelsome and turbulent, and was wholly valueless as a soldier. Not more than a week before this time he got drunk at Shrovetide; and in spite of all threats and exhortations, and his attachment to his cannon, he got tipsy and quarrelsome on the first Monday in Lent. Throughout the fast, notwithstanding the order for all in the division to eat meat, he lived on hard-tack alone, and in the first week* he did not even take the prescribed allowance of vodka. However, it was necessary to see this short figure, tough as iron, with his stumpy, crooked legs, his shiny face with its mustache, when he, for example, under the influence of liquor, took the balaláïka, or three-stringed guitar of the Ukraïna, into his strong hands, and, carelessly glancing to this side and that, played some love-song, or with his cloak thrown over his shoulders, and the orders dangling from it, and his hands thrust into the pockets of his blue nankeen trousers, he rolled along the street; it was necessary to see his expression of martial pride, and his scorn for all that did not pertain to the military,—to comprehend how absolutely impossible it was for him to compare himself at such moments with the rude or the simply insinuating servant, the Cossack, the foot-soldier, or the volunteer, especially those who did not belong to the artillery. He quarreled and was turbulent, not so much for his own pleasure as for the sake of upholding the spirit of all soldierhood, of which he felt himself to be the protector.

The third soldier, with ear-rings in his ears, with bristling mustaches, goose-flesh, and a porcelain pipe in his lips, crouching on his heels in front of the bonfire, was the artillery-rider Chikin. The dear man Chikin, as the soldiers called him, was a jester. In bitter cold, up to his knees in the mud, going without food two days at a time, on the march, on parade, undergoing instruction, the dear man always and everywhere screwed his face into grimaces, executed flourishes with his legs, and poured out such a flood of nonsense that the whole platoon would go into fits of laughter. During a halt or in camp Chikin had always around him a group of young soldiers, whom he either played* cards with, or amused with tales about some sly soldier or English milord, or by imitating the Tatar and the German, or simply by making his jokes, at which everybody nearly died with laughter. It was a fact, that his reputation as a joker was so widespread in the battery, that he had only to open his mouth and wink, and he would be rewarded with a universal burst of guffaws; but he really had a great gift for the comic and unexpected. In every thing he had the wit to see something remarkable, such as never came into anybody else's head; and, what is more important, this talent for seeing something ridiculous never failed under any trial.

The fourth soldier was an awkward young fellow, a recruit of the last year's draft, and he was now serving in an expedition for the first time. He was standing in the very smoke, and so close to the fire that it seemed as if his well-worn short-coat[6] would catch on fire; but, notwithstanding this, by the way in which he had flung open his coat, by his calm, self-satisfied pose, with his calves arched out, it was evident that he was enjoying perfect happiness.

And finally, the fifth soldier, sitting some little distance from the fire, and whittling a stick, was Uncle Zhdánof. Zhdánof had been in service the longest of all the soldiers in the battery,—knew all the recruits; and everybody, from force of habit, called him dy'á-denka, or little uncle. It was said that he never drank, never smoked, never played cards (not even the soldier's pet game of noski), and never indulged in bad talk. All the time when military duties did not engross him he worked at his trade of shoemaking; on holidays he went to church wherever it was possible, or placed a farthing candle before the image, and read* the psalter, the only book in which he cared to read. He had little to do with the other soldiers,—with those higher in rank,—though to the younger officers he was coldly respectful. With his equals, since he did not drink, he had little reason for social intercourse; but he was extremely fond of recruits and young soldiers: he always protected them, read them their lessons, and often helped them. All in the battery considered him a capitalist, because he had twenty-five rubles, which he willingly loaned to any soldier who really needed it. That same Maksímof who was now artillerist used to tell me that when, ten years before, he had come as a recruit, and the old drunken soldiers helped him to drink up the money that he had, Zhdánof, pitying his unhappy situation, took him home with him, severely upbraided him for his behavior, even administered a castigation, read him the lesson about the duties of a soldier's life, and sent him away after presenting him with a shirt (for Maksímof hadn't one to his back) and a half-ruble piece.

"He made a man of me," Maksímof used to say, always with respect and gratitude in his tone. He had also taken Velenchúk's part always, ever since he came as a recruit, and had helped him at the time of his misfortune about the lost cloak, and had helped many, many others during the course of his twenty-five years' service.

In the service it was impossible to find a soldier who knew his business better, who was braver or more obedient; but he was too meek and homely to be chosen as an artillerist,[7] though he had been bombardier fifteen years. Zhdánof's one pleasure, and even passion, was music. He was exceedingly fond of some* songs, and he always gathered round him a circle of singers from among the young soldiers; and though he himself could not sing, he stood with them, and putting his hands into the pockets of his short-coat,[8] and shutting his eyes, expressed his contentment by the motions of his head and cheeks. I know not why it was, that in that regular motion of the cheeks under the mustache, a peculiarity which I never saw in any one else, I found unusual expression. His head white as snow, his mustache dyed black, and his brown, wrinkled face, gave him at first sight a stern and gloomy appearance; but as you looked more closely into his great round eyes, especially when they smiled (he never smiled with his lips), something extraordinarily sweet and almost childlike suddenly struck you.

[4] feierverker; German, Feuerwerker.

[5] odnodvortsui, of one estate; freemen, who in the seventeenth century were settled in the Ukrafoa with special privileges.

[6] polushubochek, little half shuba.

[7] feierverker.

[8] polushubka.

*

IV.

"Alas! I have forgotten my pipe; that's a misfortune, fellows," repeated Velenchúk.

"But you should smoke cikarettes,[9] dear man," urged Chikin, screwing up his mouth, and winking. "I always smoke cikarettes at home: it's sweeter."

Of course, all joined in the laugh.

"So you forgot your pipe?" interrupted Maksímof, proudly knocking out the ashes from his pipe into the palm of his left hand, and not paying any attention to the universal laughter, in which even the officers joined. "You lost it somewhere here, didn't you, Velenchúk?"

Velenchúk wheeled to right face at him, started to lift his hand to his cap, and then dropped it again.

"You see, you haven't woke up from your last evening's spree, so that you didn't get your sleep out. For such work you deserve a good raking."

"May I drop dead on this very spot, Feódor Maksímovitch, if a single drop passed my lips. I myself don't know what got into me," replied Velenchúk. "How glad I should have been to get drunk!" he muttered to himself.

"All right. But one is responsible to the chief for his brother's conduct, and when you behave this way it's perfectly abominable," said the eloquent Maksímof savagely, but still in a more gentle tone.

*

"Well, here is something strange, fellows," continued Velenchúk after a moment's silence, scratching the back of his head, and not addressing any one in particular; "fact, it's strange, fellows. I have been sixteen years in the service, and have not had such a thing happen to me. As we were told to get ready for a march, I got up, as my duty behooved. There was nothing at all, when suddenly in the park it came over me—came over me more and more; laid me out—laid me out on the ground—and everything.... And when I got asleep, I did not hear a sound, fellows. It must have been that I fainted away," he said in conclusion.

"At all events, it took all my strength to wake you up," said Antónof, as he pulled on his boot. "I pushed you, and pushed you. You slept like a log."

"See here," remarked Velenchúk, "if I had been drunk" ...

"Like a peasant-woman we had at home," interrupted Chikin. "For almost two years running she did not get down from the big oven. They tried to wake her up one time, for they thought she was asleep; but there she was, lying just as though she was dead: the same kind of sleep you had—isn't that so, clear man?"

"Just tell us, Chikin, how you led the fashion the time when you had leave of absence," said Maksímof, smiling, and winking at me as much as to say, "Don't you like to hear what the foolish fellow has to say?"

"How led the fashion, Feódor Maksímuitch?" asked Chikin, casting a quick side glance at me. "Of course, I merely told what kind of people we are here in the Kapkas."[10]

*

"Well, then, that's so, that's so. You are not a fashion leader ... but just tell us how you made them think you were commander."

"You know how I became commander for them. I was asked how we live," began Chikin, speaking rapidly, like a man who has often told the same story. "I said, 'We live well, dear man: we have plenty of victuals. At morning and night, to our delight all we soldiers get our chocolet;[11] and then at dinner every sinner has his imperial soup of barley groats, and instead of vodka, Modeira at each plate, genuine old Modeira in the cask, forty-second degree!'".

"Fine Modeira!" replied Velenchúk louder than the others, and with a burst of laughter. "Let's have some of it."

"Well, then, what did you have to tell them about the Esiatics?" said Maksímof, carrying his inquiries still further, as the general merriment subsided.

Chikin bent down to the fire, picked up a coal with his stick, put it on his pipe, and, as though not noticing the discreet curiosity aroused in his hearers, puffed for a long time in silence.

When at last he had raised a sufficient cloud of smoke, he threw away the coal, pushed his cap still farther on the back of his head, and making a grimace, and with an almost imperceptible smile, he continued: "They asked," said he, "'What kind of a person is the little Cherkés yonder? or is it the Turk that you are fighting with in the Kapkas country?' I tell 'em, 'The Cherkés here with us is not of one sort, but of different sorts. Some are like the mountaineers who live on the rocky mountain-tops, and eat stones instead of bread. The biggest of them,' I say, 'are exactly like* big logs, with one eye in the middle of the forehead, and they wear red caps;' they glow like fire, just as you do, my dear fellow," he added, addressing a young recruit, who, in fact, wore an odd little cap with a red crown.

The recruit, at this unexpected sally, suddenly sat down on the ground, slapped his knees, and burst out laughing and coughing so that he could hardly command his voice to say, "That's the kind of mountaineers we have here."

"'And,' says I, 'besides, there are the mumri,'" continued Chikin, jerking his head so that his hat fell forward on his forehead; "'they go out in pairs, like little twins,—these others. Every thing comes double with them,' says I,' and they cling hold of each other's hands, and run so queek that I tell you you couldn't catch up with them on horseback.'—'Well,' says he, 'these mumri who are so small as you say, I suppose they are born hand in hand?'" said Chikin, endeavoring to imitate the deep throaty voice of the peasant. "'Yes,' says I, 'my dear man, they are so by nature. You try to pull their hands apart, and it makes 'em bleed, just as with the Chinese: when you pull their caps off, the blood comes.'—'But tell us,' says he, 'how they kill any one.'—'Well, this is the way,' says I: 'they take you, and they rip you all up, and they reel out your bowels in their hands. They reel 'em out, and you defy them and defy them—till your soul'" ...

"Well, now, did they believe any thing you said, Chikin?" asked Maksímof with a slight smile, when those standing round had stopped laughing.

"And indeed it is a strange people, Feódor Maksímuitch: they believe every one; before God, they do.* But still, when I began to tell them about Mount Kazbek, and how the snow does not melt all summer there, they all burst out laughing at the absurdity of it. 'What a story!' they said. 'Could such a thing be possible,—a mountain so big that the snow does not melt on it?' And I say, 'With us, when the thaw comes, there is such a heap; and even after it begins to melt, the snow lies in the hollows.'—'Go away,'" said Chikin, with a concluding wink.

[9] sikhárki.

[10] Kaphas for Kavkas, Caucasus.

[11] shchikuláta id'yót na soldátá.

*

V.

The bright disk of the sun, gleaming through the milk-white mist, had now got well up; the purple-gray horizon gradually widened: but, though the view became more extended, still it was sharply defined by the delusive white wall of the fog.

In front of us, on the other side of the forest, could be seen a good-sized field. Over the field there spread from all sides the smoke, here black, here milk-white, here purple; and strange forms swept through the white folds of the mist. Far in the distance, from time to time, groups of mounted Tatars showed themselves; and the occasional reports from our rifles, guns, and cannon were heard.

"This isn't any thing at all of an action—mere boys' play," said the good Captain Khlopof.

The commander of the ninth company of cavalry,[12] who was with us as escort, rode up to our cannon, and pointing to three mounted Tatars who were just then riding under cover of the forest, more than six hundred sazhens from us, asked me to give them a shot or a shell. His request was an illustration of the love universal among all infantry officers for artillery practice.

"You see," said he, with a kindly and convincing smile, laying his hand on my shoulder, "where those two big trees are, right in front of us: one is on a white* horse, and dressed in a black Circassian coat; and directly behind him are two more. Do you see? If you please, we must" ...

"And there are three others riding along under the lee of the forest," interrupted Antónof, who was distinguished for his sharp eyes, and had now joined us with the pipe that he had been smoking concealed behind his back. "The front one has just taken his carbine from its case. It's easy to see, your Excellency."

"Ha! he fired then, fellows. See the white puff of smoke," said Velenchúk to a group of soldiers a little back of us.

"He must be aiming at us, the blackguard!" replied some one else.

"See, those fellows only come out a little way from the forest. We see the place: we want to aim a cannon at it," suggested a third. "If we could only blant a krenade into the midst of 'em, it would scatter 'em." ...

"And what makes you think you could shoot to such a tistance, dear man?" asked Chikin.

"Only five hundred or five hundred and twenty sazhens——it can't be less than that," said Maksímof coolly, as though he were speaking to himself; but it was evident that he, like the others, was terribly anxious to bring the guns into play. "If the howitzer is aimed up at an angle of forty-five degrees, then it will be possible to reach that spot; that is perfectly possible."

"You know, now, that if you aim at that group, it would infallibly hit some one. There, there! as they are riding along now, please hurry up and order the gun to be fired," continued the cavalry commander, beseeching me.

*

"Will you give the order to limber the gun?" asked Antónof suddenly, in a jerky base voice, with a slight touch of surliness in his manner.

I confess that I myself felt a strong desire for this, and I commanded the second cannon to be unlimbered.

The words had hardly left my mouth ere the bomb was powdered and rammed home; and Antónof, clinging to the gun-cheek, and leaning his two fat fingers on the carriage, was already getting the gun into position.

"Little ... little more to the left—now a little to the right—now, now the least bit more—there, that's right," said he with a proud face, turning from the gun.

The infantry officer, myself, and Maksímof, in turn sighted along the gun, and all gave expression to various opinions.

"By God! it will miss," said Velenchúk, clicking with his tongue, although he could only see over Antónof's shoulder, and therefore had no basis for such a surmise.

"By-y-y God! it will miss: it will hit that tree right in front, fellows."

"Two!" I commanded.

The men about the gun scattered. Antónof ran to one side, so as to follow the flight of the ball. There was a flash and a ring of brass. At the same instant we were enveloped in gunpowder smoke; and after the startling report, was heard the metallic, whizzing sound of the ball rushing off quicker than lightning, amid the universal silence and dying away in the distance.

Just a little behind the group of horsemen a white puff of smoke appeared; the Tatars scattered in all directions, and then the sound of a crash came to us.

*

"Capitally done!" "Ah! they take to their heels;" "See! the devils don't like it," were types of the exclamations and jests heard among the ranks of the artillery and infantry.

"If you had aimed a trifle lower, you'd have hit right in the midst of him," remarked Velenchúk. "I said it would strike the tree: it did; it took the one at the right."

[12] jägers.

*

VI.

Leaving the soldiers to argue about the Tatars taking to flight when they saw the shell, and why it was that they came there, and whether there were many in the forest, I went with the cavalry commander a few steps aside, and sat down under a tree, expecting to have some warmed chops which he had offered me. The cavalry commander, Bolkhof, was one of the officers who are called in the regiment bonjour-oli. He had property, had served before in the guards, and spoke French. But, in spite of this, his comrades liked him. He was rather intellectual, had tact enough to wear his Petersburg overcoat, to eat a good dinner, and to speak French without too much offending the sensibilities of his brother officers. As we talked about the weather, about the events of the war, about the officers known to us both, and as we became convinced, by our questions and answers, by our views of things in general, that we were mutually sympathetic, we involuntarily fell into more intimate conversation. Moreover, in the Caucasus, among men who meet in one circle, the question invariably arises, though it is not always expressed, "Why are you here?" and it seemed to me that my companion was desirous of satisfying this inarticulate question.

"When will this expedition end?" he asked lazily: "it's tiresome."

"It isn't to me," I said: "it's much more so serving on the staff."

*

"Oh, on the staff it's ten thousand times worse!" said he fiercely. "No, I mean when will this sort of thing end altogether?"

"What! do you wish that it would end?" I asked.

"Yes, all of it, altogether!... Well, are the chops ready, Nikoláief?" he inquired of his servant.

"Why do you serve in the Caucasus, then," I asked, "if the Caucasus does not please you?"

"You know wiry," he replied with an outburst of frankness: "on account of tradition. In Russia, you see, there exists a strange tradition about the Caucasus, as though it were the promised land for all sorts of unhappy people."

"Well," said I, "it's almost true: the majority of us here "...

"But what is better than all," said he, interrupting me, "is, that all of us who come to the Kavkas are fearfully deceived in our calculations; and really, I don't see why, in consequence of disappointment in love or disorder in one's affairs, one should come to serve in the Caucasus rather than in Kazan or Kaluga. You see, in Russia they imagine the Kavkas as something immense,—everlasting virgin ice-fields, with impetuous streams, with daggers, cloaks, Circassian girls,—all that is strange and wonderful; but in reality there is nothing gay in it at all. If they only knew, for example, that we have never been on the virgin ice-fields, and that there was nothing gay in it at all, and that the Caucasus was divided into the districts of Stavropol, Tiflis, and so forth" ...

"Yes," said I, laughing, "when we are in Russia we look upon the Caucasus in an absolutely different way from what we do here. Haven't you ever noticed it: when you read poetry in a language that you don't* know very well, you imagine it much better than it really is, don't you?"

"I don't know how that is, but this Caucasus doesn't please me," he said, interrupting me.

"It isn't so with me," I said: "the Caucasus is delightful to me now, but only" ...

"Maybe it is delightful," he continued with a touch of asperity, "but I know that it is not delightful to me."

"Why not?" I asked, with a view of saying something.

"In the first place, it has deceived me—all that which I expected, from tradition, to be delivered of in the Caucasus, I find in me just the same here, only with this distinction, that before, it was all on a larger scale, but now on a small and nasty scale, at each round of which I find a million petty annoyances, worriments, and miseries; in the second place, because I find that each day I am falling morally lower and lower; and principally because I feel myself incapable of service here—I cannot endure to face the danger ... simply, I am a coward." ...

He got up and looked at me earnestly.

Though this unbecoming confession completely took, me by surprise, I did not contradict him, as my messmate evidently expected me to do; but I awaited from the man himself the refutation of his words, which is always ready in such circumstances.

"You know to-day's expedition is the first time that I have taken part in action," he continued, "and you can imagine what my evening was. When the sergeant brought the order for my company to join the column, I became as pale as a sheet, and could not utter a word from emotion; and if you knew how I* spent the night! If it is true that people turn gray from fright, then I ought to be perfectly white-headed to-day, because no man condemned to death ever suffered so much from terror in a single night as I did: even now, though I feel a little more at my ease than I did last night, still it goes here in me," he added, pressing his hand to his heart. "And what is absurd," he went on to say, "while this fearful drama is playing here, I myself am eating chops and onions, and trying to persuade myself that I am very gay.... Is there any wine, Nikoláief?" he added with a yawn.

"There he is, fellows!" shouted one of the soldiers at this moment in a tone of alarm, and all eyes were fixed upon the edge of the far-off forest.

In the distance a puff of bluish smoke took shape, and, rising up, drifted away on the wind. When I realized that the enemy were firing at us, every thing that was in the range of my eyes at that moment, every thing suddenly assumed a new and majestic character. The stacked muskets, and the smoke of the bonfires, and the blue sky, and the green gun-carriages, and Nikoláief's sunburned, mustachioed face,—all this seemed to tell me that the shot which at that instant emerged from the smoke, and was flying through space, might be directed straight at my breast.

"Where did you get the wine?" I meanwhile asked Bolkhof carelessly, while in the depths of my soul two voices were speaking with equal distinctness; one said, "Lord, take my soul in peace;" the other, "I hope I shall not duck my head, but smile while the ball is coming." And at that instant something horribly unpleasant whistled above our heads, and the shot came crashing to the ground not two paces away from us.

"Now, if I were Napoleon or Frederick the Great,"* said Bolkhof at this time, with perfect composure, turning to me, "I should certainly have said something graceful."

"But that you have just done," I replied, hiding with some difficulty the panic which I felt at being exposed to such a danger.

"Why, what did I say? No one will put it on record."

"I'll put it on record."

"Yes: if you put it on record, it will be in the way of criticism, as Mishchenkof says," he replied with a smile.

"Tfu! you devils!" exclaimed Antónof in vexation just behind us, and spitting to one side; "it just missed my leg."

All my solicitude to appear cool, and all our refined phrases, suddenly seemed to me unendurably stupid after this artless exclamation.

*

VII.

The enemy, in fact, had posted two cannon on the spot where the Tatars had been scattered, and every twenty or thirty minutes sent a shot at our wood-choppers. My division was sent out into the field, and ordered to reply to him. At the skirt of the forest a puff of smoke would show itself, the report would be heard, then the whiz of the ball, and the shot would bury itself behind us or in front of us. The enemy's shots were placed fortunately for us, and no loss was sustained.

The artillerists, as always, behaved admirably, loaded rapidly, aimed carefully wherever the smoke appeared, and jested unconcernedly with each other. The infantry escort, in silent inactivity, were lying around us, awaiting their turn. The wood-cutters were busy at their work; their axes resounded through the forest more and more rapidly, more and more eagerly, save when the svist of a cannon-shot was heard, then suddenly the sounds ceased, and amid the deathlike stillness a voice, not altogether calm, would exclaim, "Stand aside, boys!" and all eyes would be fastened upon the shot ricocheting upon the wood-piles and the brush.

The fog was now completely lifted, and, taking the form of clouds, was disappearing slowly in the dark-blue vault of heaven. The unclouded orb of the sun shone bright, and threw its cheerful rays on the steel of* the bayonets, the brass of the cannon, on the thawing ground, and the glittering points of the icicles. The atmosphere was brisk with the morning frost and the warmth of the spring sun. Thousands of different shades and tints mingled in the dry leaves of the forest; and on the hard, shining level of the road could be seen the regular tracks of wheel-tires and horse-shoes.

The action between the armies grew more and more violent and more striking. In all directions the bluish puffs of smoke from the firing became more and more frequent. The dragoons, with bannerets waving from their lances, kept riding to the front. In the infantry companies songs resounded, and the train loaded with wood began to form itself as the rearguard. The general rode up to our division, and ordered us to be ready for the return. The enemy got into the bushes over against our left flank, and began to pour a heavy musketry-fire into us. From the left-hand side a ball came whizzing from the forest, and buried itself in a gun-carriage; then—a second, a third.... The infantry guard, scattered around us, jumped up with a shout, seized their muskets, and took aim. The cracking of the musketry was redoubled, and the bullets began to fly thicker and faster. The retreat had begun, and the present attack was the result, as is always the case in the Caucasus.

It became perfectly manifest that the artillerists did not like the bullets as well as the infantry had liked the solid shot. Antónof put on a deep frown. Chikin imitated the sound of the bullets, and fired his jokes at them; but it was evident that he did not like them. In regard to one he said, "What a hurry it's in!" another he called a "honey-bee;" a third, which flew over us with a sort of slow and lugubrious drone,* he called an "orphan,"—a term which raised general amusement.

The recruit, who had the habit of bending his head to one side, and stretching out his neck, every time he heard a bullet, was also a source of amusement to the soldiers, who said, "Who is it? some acquaintance that you are bowing to?" And Velenchúk, who always showed perfect equanimity in time of danger, was now in an alarming state of mind; he was manifestly vexed because we did not send some canister in the direction from which the bullets came. He more than once exclaimed in a discontented tone, "What is he allowed to shoot at us with impunity for? If we could only answer with some grape, that would silence him, take my word for it."

In fact, it was time to do this. I ordered the last shell to be fired, and to load with grape.

"Grape!" shouted Antónof bravely in the midst of the smoke, coming up to the gun with his sponge as soon as the discharge was made.

At this moment, not far-behind us, I heard the quick whiz of a bullet suddenly striking something with a dry thud. My heart sank within me. "Some one of our men must have been struck," I said to myself; but at the same time I did not dare to turn round, under the influence of this powerful presentiment. True enough, immediately after this sound the heavy fall of a body was heard, and the "o-o-o-oï,"—the heart-rending groan of the wounded man. "I'm hit, fellows," remarked a voice which I knew. It was Velenchúk. He was lying on his back between the limbers and the gun. The cartridge-box which he carried was flung to one side. His forehead was all bloody, and over his right eye and his nose flowed a* thick red stream. The wound was in his body, but it bled very little; he had hit his forehead on something when he fell.

All this I perceived after some little time. At the first instant I saw only a sort of obscure mass, and a terrible quantity of blood as it seemed to me.

None of the soldiers who were loading the gun said a word,—only the recruit muttered between his teeth, "See, how bloody!" and Antónof, frowning still blacker, snorted angrily; but all the time it was evident that the thought of death presented itself to the mind of each. All took hold of their work with great activity. The gun was discharged every instant; and the gun-captain, in getting the canister, went two steps around the place where lay the wounded man, now groaning constantly.

*

VIII.

Evert one who has been in action has doubtless experienced the strange although illogical but still powerful feeling of repulsion for the place in which any one has been killed or wounded. My soldiers were noticeably affected by this feeling at the first moment when it became necessary to lift Velenchúk and carry him to the wagon which had driven up. Zhdánof angrily went to the sufferer, and, notwithstanding his cry of anguish, took him under his arms and lifted him. "What are you standing there for? Help lug him!" he shouted; and instantly the men sprang to his assistance, some of whom could not do any good at all. But they had scarcely started to move him from the place when Velenchúk began to scream fearfully and to struggle.

"What are you screeching for, like a rabbit?" said Antónof, holding him roughly by the leg. "If you don't stop we'll drop you."

And the sufferer really calmed down, and only occasionally cried out, "Okh! I'm dead! o-okh, fellows![13] I'm dead!"

As soon as they laid him in the wagon, he ceased to groan, and I heard that he said something to his comrades—it must have been a farewell—in a weak but audible voice.

Indeed, no one likes to look at a wounded man; and* I, instinctively hastening to get away from this spectacle, ordered the men to take him as soon as possible to a suitable place, and then return to the guns. But in a few minutes I was told that Velenchúk was asking for me, and I returned to the ambulance.

The wounded man lay on the wagon bottom, holding the sides with both hands. His healthy, broad face had in a few seconds entirely changed; he had, as it were, grown gaunt, and older by several years. His lips were pinched and white, and tightly compressed, with evident effort at self-control; his glance had a quick and feeble expression; but in his eyes was a peculiarly clear and tranquil gleam, and on his blood-stained forehead and nose already lay the seal of death.

In spite of the fact that the least motion caused him unendurable anguish, he was trying to take from his left leg his purse,[14] which contained money.

A fearfully burdensome thought came into my mind when I saw his bare, white, and healthy-looking leg as he was taking off his boot and untying his purse.

"There are three silver rubles and a fifty-kopeck piece," he said when I took the girdle-purse. "You keep them."

The ambulance had started to move, but he stopped it.

"I was working on a cloak for Lieutenant Sulimovsky. He had paid me two-o-o silver rubles. I spent one and a half on buttons, but half a ruble lies with the buttons in my bag. Give them to him."

"Very good, I will," said I. "Keep up good hopes, brother."

*

He did not answer me; the wagon moved away, and he began once more to groan, and to exclaim "Okh!" in the same terribly heart-rending tone. As though he had done with earthly things, he felt that he had no longer any pretext for self-restraint, and he now considered this alleviation permissible.

[13] bratsuí moï.

[14] chéres; diminutive, chéresok,—a leather purse in the form of a girdle, which soldiers wear usually under the knee.—AUTHOR'S NOTE.

*

IX.

"Where are you off to? Come back! Where are you going?" I shouted to the recruit, who, carrying in his arms his reserve linstock, and a sort of cane in his hand, was calmly marching off toward the ambulance in which the wounded man was carried.

But the recruit lazily looked up at me, and kept on his way, and I was obliged to send a soldier to bring him back. He took off his red cap, and looked at me with a stupid smile.

"Where were you going?" I asked.

"To camp."

"Why?"

"Because—they have wounded Velenchúk," he replied, still smiling.

"What has that to do with you? It's your business to stay here."

He looked at me in amazement, then coolly turned round, put on his cap, and went to his place.

The result of the action had been fortunate. The Cossacks, it was reported, had made a brilliant attack, and had captured three bodies of the Tatars; the infantry had laid in a store of firewood, and had suffered in all a loss of six men wounded. In the artillery, from the whole array only Velenchúk and two horses were put hors du combat. Moreover, they had cut the forest for three versts, and cleared a place, so that it was impossible to recognize it; now,* instead of a seemingly impenetrable forest girdle, a great field was opened up, covered with heaps of smoking bonfires, and lines of infantry and cavalry on their way to camp. Notwithstanding the fact that the enemy incessantly harassed us with cannonade and musketry, and followed us down to the very river where the cemetery was, that we had crossed in the morning, the retreat was successfully managed.

I was already beginning to dream of the cabbage-soup and rib of mutton with kasha gruel that were awaiting me at the camp, when the word came, that the general had commanded a redoubt to be thrown up on the river-bank, and that the third battalion of regiment K, and a division of the fourth battery, should stay behind till the next day for that purpose. The wagons with the firewood and the wounded, the Cossacks, the artillery, the infantry with muskets and fagots on their shoulders,—all with noise and songs passed by us. On the faces of all shone enthusiasm and content, caused by the return from peril, and hope of rest; only we and the men of the third battalion were obliged to postpone these joyful feelings till the morrow.

*

X.

While we of the artillery were busy about the guns, disposing the limbers and caissons, and picketing the horses, the foot-soldiers had stacked their arms, piled up bonfires, made shelters of boughs and cornstalks, and were cooking their grits.

It began to grow dark. Across the sky swept bluish-white clouds. The mist, changing into fine drizzling fog, began to wet the ground and the soldiers' cloaks. The horizon became contracted, and all our surroundings took on gloomy shadows. The dampness which I felt through my boots and on my neck, the incessant motion and chatter in which I took no part, the sticky mud with which my legs were covered, and my empty stomach, all combined to arouse in me a most uncomfortable and disagreeable frame of mind after a day of physical and moral fatigue. Velenchúk did not go out of my mind. The whole simple story of his soldier's life kept repeating itself before my imagination.

His last moments were as unclouded and peaceful as all the rest of his life. He had lived too honestly and simply for his artless faith in the heavenly life to come, to be shaken at the decisive moment.

"Your health," said Nikoláïef, coming to me. "The captain begs you to be so kind as to come and drink tea with him."

Somehow making my way between stacks of arms* and the camp-fires, I followed Nikoláïef to where Captain Bolkhof was, and felt a glow of satisfaction in dreaming about the glass of hot tea and the gay converse which should drive away my gloomy thoughts.

"Well, has he come?" said Bolkhof's voice from his cornstalk wigwam, in which the light was gleaming.

"He is here, your honor,"[15] replied Nikoláïef in his deep bass.

In the hut, on a dry burka, or Cossack mantle, sat the captain in négligé, and without his cap. Near him the samovar was singing, and a drum was standing, loaded with lunch. A bayonet stuck into the ground held a candle.

"How is this?" he said with some pride, glancing around his comfortable habitation. In fact, it was so pleasant in his wigwam, that, while we were at tea I absolutely forgot about the dampness, the gloom, and Velenchúk's wound. We talked about Moscow and subjects that had no relation to the war or the Caucasus.

After one of the moments of silence which sometimes interrupt the most lively conversations, Bolkhof looked at me with a smile.

"Well, I suppose our talk this morning must have seemed very strange to you?" said he.

"No. Why should it? It only seemed to me that you were very frank; but there are things which we all know, but which it is not necessary to speak about."

"Oh, you are mistaken! If there were only some possibility of exchanging this life for any sort of life, no matter how tame and mean, but free from danger and service, I would not hesitate a minute."

*

"Why, then, don't you go back to Russia?" I asked.

"Why?" he repeated. "Oh, I have been thinking about that for a long time. I can't return to Russia until I have won the Anna and Vladímir, wear the Anna ribbon around my neck, and am major, as I expected when I came here."

"Why not, pray, if you feel that you are so unfitted as you say for service here?"

"Simply because I feel still more unfitted to return to Russia the same as I came. That also is one of the traditions existing in Russia which were handed down by Passek, Sleptsof, and others,—that you must go to the Caucasus, so as to come home loaded with rewards. And all of us are expecting and working for this; but I have been here two years, have taken part in two expeditions, and haven't won any thing. But still, I have so much vanity that I shall not go away from here until I am, major, and have the Vladímir and Anna around my neck. I am already accustomed to having every thing avoid me, when even Gnilokishkin gets promoted, and I don't. And so how could I show myself in Russia before the eyes of my elder, the merchant Kotelnikof, to whom I sell wheat, or to my auntie in Moscow, and all those people, if I had served two years in the Caucasus without getting promoted? It is true that I don't wish to know these people, and, of course, they don't care very much about me; but a man is so constituted, that though I don't wish to know them, yet on account of them I am wasting my best years, and destroying all the happiness of my life, and all my future."

[15] váshie blagoródié.

*

XI.

At this moment the voice of the battalion commander was heard on the outside, saying, "Who is it with you, Nikoláï Feódorovitch?" Bolkhof mentioned my name, and in a moment three officers came into the wigwam,—Major Kirsánof, the adjutant of his battalion, and company commander Trosenko.

Kirsánof was a short, thick-set fellow, with black mustaches, ruddy cheeks, and little oily eyes. His little eyes were the most noticeable features of his physiognomy. When he laughed, there remained of them only two moist little stars; and these little stars, together with his pursed-up lips and long neck, sometimes gave him a peculiar expression of insipidity. Kirsánof considered himself better than any one else in the regiment. The under officers did not dispute this; and the chiefs esteemed him, although the general impression about him was, that he was very dull-witted. He knew his duties, was accurate and zealous, kept a carriage and a cook, and, naturally enough, managed to pass himself off as arrogant.

"What are you gossiping about, captain?" he asked as he came in.

"Oh, about the delights of the service here."

But at this instant Kirsánof caught sight of me, a mere yunker; and in order to make me gather a high impression of his knowledge, as though he had not* heard Bolkhof's answer, and glancing at the drum, he asked,—

"What, were you tired, captain?"

"No. You see, we" ... began Bolkhof.

But once more, and it must have been the battalion commander's dignity that caused him to interrupt the answer, he put a new question:—

"Well, we had a splendid action to-day, didn't we?"

The adjutant of the battalion was a young fellow who belonged to the fourteenth army-rank, and had only lately been promoted from the yunker service. He was a modest and gentle young fellow, with a sensitive and good-natured face. I had met him before at Bolkhof's. The young man would come to see him often, make him a bow, sit down in a corner, and for hours at a time say nothing, and only make cigarettes and smoke them; and then he would get up, make another bow, and go away. He was the type of the poor son of the Russian noble family, who has chosen the profession of arms as the only one open to him in his circumstances, and who values above every thing else in the world his official calling,—an ingenuous and lovable type, notwithstanding his absurd, indefeasible peculiarities: his tobacco-pouch, his dressing-gown, his guitar, and his mustache brush, with which we used to picture him to ourselves. In the regiment they used to say of him that he boasted of being just but stern with his servant, and quoted him as saying, "I rarely punish; but when I am driven to it, then let 'em beware:" and once, when his servant got drunk, and plundered him, and began to rail at his master, they say he took him to the guard-house, and commanded them to have every thing ready for the chastisement;* but when he saw the preparations, he was so confused, that he could only stammer a few meaningless words: "Well, now you see—I might," ... and, thoroughly upset, he set off home, and from that time never dared to look into the eyes of his man. His comrades gave him no peace, but were always nagging him about this; and I often heard how the ingenuous lad tried to defend himself, and, blushing to the roots of his hair, avowed that it was not true, but absolutely false.

The third character, Captain Trosenko, was an old Caucasian[16] in the full acceptation of the word: that is, he was a man for whom the company under his command stood for his family; the fortress where the staff was, his home; and the song-singers his only pleasure in life,—a man for whom every thing that was not Kavkas was worthy of scorn, yes, was almost unworthy of belief; every thing that was Kavkas was divided into two halves, ours and not ours. He loved the first, the second he hated with all the strength of his soul. And, above all, he was a man of iron nerve, of serene bravery, of rare goodness and devotion to his comrades and subordinates, and of desperate frankness, and even insolence in his bearing, toward those who did not please him; that is, adjutants and bon jourists. As he came into the wigwam, he almost bumped his head on the roof, then suddenly sank down and sat on the ground.

"Well, how is it?"[17] said he; and suddenly becoming cognizant of my presence, and recognizing me, he got up, turning upon me a troubled, serious gaze.

"Well, why were you talking about that?" asked the major, taking out his watch and consulting it,* though I verily believe there was not the slightest necessity of his doing so.

"Well,[18] he asked me why I served here."

"Of course, Nikoláï Feódorovitch wants to win distinction here, and then go home."

"Well, now, you tell us, Abram Ilyitch, why you serve in the Caucasus."

"I? Because, as you know, in the first place we are all in duty bound to serve. What?" he added, though no one spoke. "Yesterday evening I received a letter from Russia, Nikoláï Feódorovitch," he continued, eager to change the conversation. "They write me that ... what strange questions are asked!"

"What sort of questions?" asked Bolkhof.

He blushed.

"Really, now, strange questions ... they write me, asking, 'Can there be jealousy without love?' ... What?" he asked, looking at us all.

"How so?" said Bolkhof, smiling.

"Well, you know, in Russia it's a good thing," he continued, as though his phrases followed each other in perfectly logical sequence. "When I was at Tambof in '52 I was invited everywhere, as though I were on the emperor's suite. Would you believe me, at a ball at the governor's, when I got there ... well, don't you know, I was received very cordially. The governor's wife[19] herself, you know, talked with me, and asked me about the Caucasus; and so did all the rest ... why, I don't know ... they looked at my gold cap as though it were some sort of curiosity, and they asked me how I had won it, and how about the Anna and the Vladímir; and I told them all about it.... What? That's why the Caucasus is good,* Nikoláï Feódorovitch," he continued, not waiting for a response. "There they look on us Caucasians very kindly. A young man, you know, a staff-officer with the Anna and Vladímir,—that means a great deal in Russia. What?"

"You boasted a little, I imagine, Abram Ilyitch," said Bolkhof.

"He-he," came his silly little laugh in reply. "You know, you have to. Yes, and didn't I feed royally those two months!"

"So it is fine in Russia, is it?" asked Trosenko, asking about Russia as though it were China or Japan.

"Yes, indeed![20] We drank so much champagne there in those two months, that it was a terror!"

"The idea! you?[21] You drank lemonade probably. I should have died to show them how the Kavkázets drinks. The glory has not been won for nothing. I would show them how we drink.... Hey, Bolkhof?" he added.

"Yes, you see, you have been already ten years in the Caucasus, uncle," said Bolkhof, "and you remember what Yermolof said; but Abram Ilyitch has been here only six." ...

"Ten years, indeed! almost sixteen."

"Let us have some salvia, Bolkhof: it's raw, b-rr! What?" he added, smiling, "shall we drink, major?"

But the major was out of sorts, on account of the old captain's behavior to him at first; and now he evidently retired into himself, and took refuge in his own greatness. He began to hum some song, and again looked at his watch.

"Well, I shall never go there again," continued Trosenko,* paying no heed to the peevish major. "I have got out of the habit of going about and speaking Russian. They'd ask, 'What is this wonderful creature?' and the answer'd be, 'Asia.' Isn't that so, Nikoláï Feódoruitch? And so what is there for me in Russia? It's all the same, you'll get shot here sooner or later. They ask, 'Where is Trosenko?' And down you go! What will you do then in the eighth company—heh?" he added, continuing to address the major.

"Send the officer of the day to the battalion," shouted Kirsánof, not answering the captain, though I was again compelled to believe that there was no necessity upon him of giving any orders.

"But, young man, I think that you are glad now that you are having double pay?" said the major after a few moments' silence, addressing the adjutant of the battalion.

"Why, yes, very."

"I think that our salary is now very large, Nikoláï Feódoruitch," he went on to say. "A young man can live very comfortably, and even allow himself some little luxury."

"No, truly, Abram Ilyitch," said the adjutant timidly: "even though we get double pay, it's only so much; and you see, one must keep a horse." ...

"What is that you say, young man? I myself have been an ensign, and I know. Believe me, with care, one can live very well. But you must calculate," he added, tapping his left palm with his little finger.

"We pledge all our salary before it's due: this is the way you economize," said Trosenko, drinking down a glass of vodka.

*

"Well, now, you see that's the very thing.... What?"

At this instant at the door of the wigwam appeared a white head with a flattened nose; and a sharp voice with a German accent said,—

"You there, Abram Ilyitch? The officer of the day is hunting for you."

"Come in, Kraft," said Bolkhof.

A tall form in the coat of the general's staff entered the door, and with remarkable zeal endeavored to shake hands with every one.

"Ah, my dear captain, you here too?" said he, addressing Trosenko.

The new guest, notwithstanding the darkness, rushed up to the captain and kissed him on the lips, to his extreme astonishment, and displeasure as it seemed to me.

"This is a German who wishes to be a hail fellow well met," I said to myself.

[16] Kavkázets.

[17] nu chto?

[18] da voi.

[19] gubernátorsha.

[20] da s.

[21] da chto vui.

*

XII.

My presumption was immediately confirmed. Captain Kraft called for some vodka, which he called corn-brandy,[22] and threw back his head, and made a terrible noise like a duck, in draining the glass.

"Well, gentlemen, we rolled about well to-day on the plains of the Chetchen," he began; but, catching sight of the officer of the day, he immediately stopped, to allow the major to give his directions.

"Well, you have made the tour of the lines?"

"I have."

"Are the pickets posted?"

"They are."

"Then you may order the captain of the guard to be as alert as possible."

"I will."

The major blinked his eyes, and went into a brown study.

"Well, tell the boys to get their supper."

"That's what they're doing now."

"Good! then you may go. Well,"[23] continued the major with a conciliating smile, and taking up the thread of the conversation that we had dropped, "we were reckoning what an officer needed: let us finish the calculation."

"We need one uniform and trousers, don't we?"[24]

"Yes. That, let us suppose would amount to fifty* rubles every two years; say, twenty-five rubles a year for dress. Then for eating we need every day at least forty kopecks, don't we?[25]"

"Yes, certainly as much as that."

"Well, I'll call it so. Now, for a horse and saddle for remount, thirty rubles; that's all. Twenty-five and a hundred and twenty and thirty make a hundred and seventy-five rubles. All the rest stands for luxuries,—for tea and for sugar and for tobacco,—twenty rubles. Will you look it over?... It's right, isn't it, Nikoláï Feódoruitch?"

"Not quite. Excuse me, Abram Ilyitch," said the adjutant timidly, "nothing is left for tea and sugar. You reckon one suit for every two years, but here in field-service you can't get along with one pair of pantaloons and boots. Why, I wear out a new pair almost every month. And then linen, shirts, handkerchiefs, and leg-wrappers: all that sort of thing one has to buy. And when you have accounted for it, there isn't any thing left at all. That's true, by God![26] Abram Ilyitch."

"Yes, it's splendid to wear leg-wrappers," said Kraft suddenly, after a moment's silence, with a loving emphasis on the word "leg-wrappers;"[27] "you know it's simply Russian fashion."

"I will tell you," remarked Trosenko, "it all amounts to this, that our brother imagines that we have nothing to eat; but the fact is, that we all live, and have tea to drink, and tobacco to smoke, and our vodka to drink. If you served with me," he added, turning to the ensign, "you would soon learn how to live. I suppose you gentlemen know how he treated his denshchik."

And Trosenko, dying with laughter, told us the* whole story of the ensign and his man, though we had all heard it a thousand times.

"What makes you look so rosy, brother?" he continued, pointing to the ensign, who turned red, broke into a perspiration, and smiled with such constraint that it was painful to look at him.

"It's all right, brother. I used to be just like you; but now, you see, I have become hardened. Just let any young fellow come here from Russia,—we have seen 'em,—and here they would get all sorts of rheumatism and spasms; but look at me sitting here: it's my home, and bed, and all. You see" ... Here he drank still another glass of vodka. "Ha?" he continued, looking straight into Kraft's eyes.

"That's what I like in you. He's a genuine old Kavkázets. Kive us your hant."

And Kraft pushed through our midst, rushed up to Trosenko, and, grasping his hand, shook it with remarkable feeling.

"Yes, we can say that we have had all sorts of experiences here," he continued. "In '45 you must have been there, captain? Do you remember the night of the 24th and 25th, when we camped in mud up to our knees, and the next day went against the entrenchments? I was then with the commander-in-chief, and in one day we captured fifteen entrenchments. Do you remember, captain?"

Trosenko nodded assent, and, pushing out his lower lip, closed his eyes.

"You ought to have seen," Kraft began with extraordinary animation, making awkward gestures with his arms, and addressing the major.

But the major, who must have more than once heard this tale, suddenly threw such an expression of muddy* stupidity into his eyes, as he looked at his comrade, that Kraft turned from him, and addressed Bolkhof and me, alternately looking at each of us. But he did not once look at Trosenko, from one end of his story to the other.

"You ought to have seen how in the morning the commander-in-chief came to me, and says, 'Kraft, take those entrenchments.' You know our military duty,—no arguing, hand to visor. 'It shall be done, your Excellency,'[28] and I started. As soon as we came to the first entrenchment, I turn round, and shout to the soldiers, 'Poys, show your mettle! Pe on your guard. The one who stops I shall cut down with my own hand.' With Russian soldiers you know you have to be plain-spoken. Then suddenly comes a shell—I look—one soldier, two soldiers, three soldiers, then the bullets—vz-zhin! vz-zhin! vz-zhin! I shout, 'Forward, boys; follow me!' As soon as we reach it, you know, I look and see—how it—you know: what do you call it?" and the narrator waved his hands in his search for the word.

"Rampart," suggested Bolkhof.

"No.... Ach! what is it? My God, now, what is it?... Yes, rampart," said he quickly. "Then clubbing their guns!... hurrah! ta-ra-ta-ta-ta! The enemy—not a soul was left. Do you know, they were amazed. All right. We rush on—the second entrenchment. This was quite a different affair. Our hearts poiled within us, you know. As soon as we got there, I look and I see the second entrenchment—impossible to mount it. There—what was it—what was it we just called it? Ach! what was it?" ...

"Rampart," again I suggested.

*

"Not at all," said he with some heat. "Not rampart. Ah, now, what is it called?" and he made a sort of despairing gesture with his hand. "Ach! my God! what is it?" ...

He was evidently so cut up, that one could not help offering suggestions.

"Moat, perhaps," said Bolkhof.

"No; simply rampart. As soon as we reached it, if you will believe me, there was a fire poured in upon us—it was hell." ...

At the crisis, some one behind the wigwam inquired for me. It was Maksímof. As there still remained thirteen of the entrenchments to be taken in the same monotonous detail, I was glad to have an excuse to go to my division. Trosenko went with me.

"It's all a pack of lies," he said to me when we had gone a few steps from the wigwam. "He wasn't at the entrenchments at all;" and Trosenko laughed so good-naturedly, that I could not help joining him.