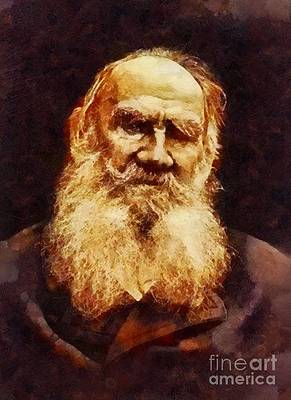

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1890

Source: Original text from RevoltLib.com; Translated by Louise and Aylmer Maude

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

What is the explanation of the fact that people use things that stupefy them: vódka, wine, beer, hashish, opium, tobacco, and other things less common: ether, morphia, fly-agaric, etc.? Why did the practice begin? Why has it spread so rapidly, and why is it still spreading among all sorts of people, savage and civilized? How is it that where there is no vódka, wine or beer, we find opium, hashish, fly-agaric, and the like, and that tobacco is used everywhere?

Why do people wish to stupefy themselves?

Ask anyone why he began drinking wine and why he now drinks it. He will reply, “Oh, I like it, and everybody drinks,” and he may add, “it cheers me up.” Some—those who have never once taken the trouble to consider whether they do well or ill to drink wine—may add that wine is good for the health and adds to one's strength; that is to say, will make a statement long since proved baseless.

Ask a smoker why he began to use tobacco and why he now smokes, and he also will reply: “To while away the time; everybody smokes.”

Similar answers would probably be given by those who use opium, hashish, morphia, or fly-agaric.

'To while away time, to cheer oneself up; everybody does it.' But it might be excusable to twiddle one's thumbs, to whistle, to hum tunes, to play a fife or to do something of that sort 'to while away the time,' 'to cheer oneself up,' or 'because everybody does it' — that is to say, it might be excusable to do something which does not involve wasting Nature's wealth, or spending what has cost great labor to produce, or doing what brings evident harm to oneself and to others.

But to produce tobacco, wine, hashish, and opium, the labor of millions of men is spent, and millions and millions of acres of the best land (often amid a population that is short of land) are employed to grow potatoes, hemp, poppies, vines, and tobacco.

Moreover, the use of these evidently harmful things produces terrible evils known and admitted by everyone, and destroys more people than all the wars and contagious diseases added together. And people know this, so that they cannot really use these things 'to while away time,' 'to cheer themselves up,' or because 'everybody does it.'

There must be some other reason. Continually and everywhere one meets people who love their children and are ready to make all kinds of sacrifices for them, but who yet spend on vódka, wine and beer, or on opium, hashish, or even tobacco, as much as would quite suffice to feed their hungry and poverty-stricken children, or at least as much as would suffice to save them from misery.

Evidently if a man who has to choose between the want and sufferings of a family he loves on the one hand, and abstinence from stupefying things on the other, chooses the former — he must be induced thereto by something more potent than the consideration that everybody does it, or that it is pleasant. Evidently it is done not 'to while away time,' nor merely 'to cheer himself up.' He is actuated by some more powerful cause.

This cause — as far as I have detected it by reading about this subject and by observing other people, and particularly by observing my own case when I used to drink wine and smoke tobacco — this cause, I think, may be explained as follows:

When observing his own life, a man may often notice in himself two different beings: the one is blind and physical, the other sees and is spiritual. The blind animal being eats, drinks, rests, sleeps, propagates, and moves, like a wound-up machine. The seeing, spiritual being that is bound up with the animal does nothing of itself, but only appraises the activity of the animal being; coinciding with it when approving its activity, and diverging from it when disapproving.

This observing being may be compared to the needle of a compass, pointing with one end to the north and with the other to the south, but screened along its whole length by something not noticeable so long as it and the needle both point the same way; but which becomes obvious as soon as they point different ways.

In the same manner the seeing, spiritual being, whose manifestation we commonly call conscience, always points with one end towards right and with the other towards wrong, and we do not notice it while we follow the course it shows: the course from wrong to right. But one need only do something contrary to the indication of conscience to become aware of this spiritual being, which then shows how the animal activity has diverged from the direction indicated by conscience.

And as a navigator conscious that he is on the wrong track cannot continue to work the oars, engine, or sails, till he has adjusted his course to the indications of the compass, or has obliterated his consciousness of this divergence—each man who has felt the duality of his animal activity and his conscience can continue his activity only by adjusting that activity to the demands of conscience, or by hiding from himself the indications conscience gives him of the wrongness of his animal life.

All human life, we may say, consists solely of these two activities:

Some do the first, others the second. To attain the first there is but one means: moral enlightenment — the increase of light in oneself and attention to what it shows. To attain the second — to hide from oneself the indications of conscience—there are two means: one external and the other internal. The external means consists in occupations that divert one's attention from the indications given by conscience; the internal method consists in darkening conscience itself.

As a man has two ways of avoiding seeing an object that is before him: either by diverting his sight to other more striking objects, or by obstructing the sight of his own eyes—just so a man can hide from himself the indications of conscience in two ways: either by the external method of diverting his attention to various occupations, cares, amusements, or games; or by the internal method of obstructing the organ of attention itself.[1]

For people of dull, limited moral feeling, the external diversions are often quite sufficient to enable them not to perceive the indications conscience gives of the wrongness of their lives. But for morally sensitive people those means are often insufficient.

The external means do not quite divert attention from the consciousness of discord between one's life and the demands of conscience. This consciousness hampers one's life; and in order to be able to go on living as before, people have recourse to the reliable, internal method, which is that of darkening conscience itself by poisoning the brain with stupefying substances.

One is not living as conscience demands, yet lacks the strength to reshape one's life in accord with its demands. The diversions which might distract attention from the consciousness of this discord are insufficient, or have become stale, and so—in order to be able to live on, disregarding the indications conscience gives of the wrongness of their life—people (by poisoning it temporarily) stop the activity of the organ [the brain] through which conscience manifests itself, as a man by covering his eyes hides from himself what he does not wish to see.